Enforcement of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was always going to be a tough sell. COVID-19 will make it worse.

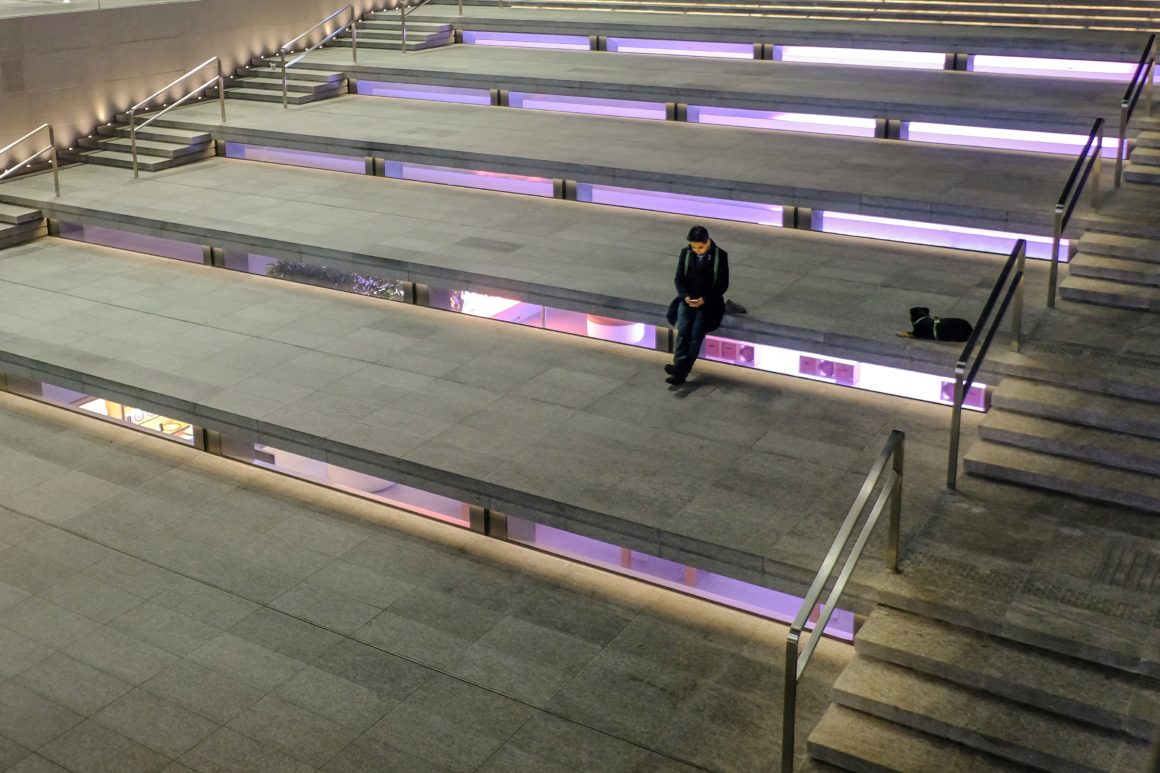

A man looks at his smartphone while sitting with his dog on the steps of the closed Apple Store on Piazza del Liberty in downtown Milan, Italy

15 May 2020 (Brussels, Belgium) – Enforcement of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). A tough task. It was always going to be a tough sell. All of the “consent” elements and many of the compliance elements are nebulous, much of the connective tissue between sections having been stripped out during negotiations, aided and abetted by law firms and consultants and vendors hired by Big Tech to do everything possible to cripple it. Many of those same law firms and consultants and vendors pop up at compliance conferences to sell you their services to comply with it. John Kander had it right in “Cabaret” : money, and only money, truly makes the world go round.

I was fortunate to watch the process over its four year gestation, living in Brussels and having contacts with EU Commission insiders. To watch the machinations of Big Tech was a Master Class in manipulation. And to hear the various regulators claiming to be “overwhelmed” and that this GDPR thing “dropped out of the sky” when they had over 2+ years to prepare, budget, and hire before the enforcement date of 25 May 2018 – and time to complain about preparation, budget, and staffing issues beforehand – was a Master Class in incompetence.

The fundamental problem was always the collection of data, not its control. Europe introduced the GDPR aimed at curbing abuses of customer data. But the legislation misdiagnosed the problems. It should have tackled the collection of data, not its protection once collected. As I reported several years ago, when the GDPR drafting first began, the focus was on limiting collection but Big Tech lobbyists and lawyers turned that premise 180 degrees and “control” became the operative word. That has always been Big Tech’s mantra: don’t ask permission. Just do it, and then apologise later if it goes bad. Zuckerberg is the poster boy for that mantra.

Data isn’t harmless, data isn’t abstract when it’s about people. Almost all the data being collected today is about people. It is not data that is being exploited, it’s people that are exploited. It’s not data in networks being influenced or manipulated, it is us being manipulated.

So when control is the “north star” then lawmakers aren’t left with much to work with. It’s not clear that more control and more choices are actually going to help us. What is the end game we’re actually hoping for with control? If data processing is so dangerous that we need these complicated controls, maybe we should just not allow the processing at all? How about that idea? Anybody?

Had regulators really wanted to help they would have stopped forcing complex control burdens on citizens, and made real rules that mandate deletion or forbid collection in the first place for high risk activities. But they could not. They lost control of the narrative. As I have noted in a series of posts, as soon as the new GDPR negotiations were in process 4+ years ago the Silicon Valley elves sent their army of lawyers and lobbyists to control the narrative to be about “control” burdens on citizens. The regulators had their chance but they got played. Because despite all the sound and fury, the implication of fully functioning privacy in a digital democracy is that individuals would control and manage their own data and organizations would have to request access to that data. Not the other way around. But the tech companies know it is too late now (despite calls for a GDPR “rewrite”) to impose that structure so they will make sure any new rules that seek to redress any errors work in their favor.

The GDPR came about as a swipe against American Big Tech. Let’s not beat about the bush. The EU wanted to take them down a peg. But the opposite happened. Marketers are spending more of their ad dollars with the biggest players … in particular Facebook and Google .. whom they trust not to run afoul of the GDPR rules and who have the financial firepower to deal with it. So these small marketers can hide in their aprons. And as a presenter said at a Zoom legal workshop on the GDPR in Brussels yesterday “how different countries will enforce the major bits of the regulation is still to be determined, and it’s probably years out, so any uniform standard for the use of data in digital advertising is unlikely to materialize for quite a number of years.”

Now, no doubt, the rules have made it harder for third parties to collect lucrative personal information like location data in Europe to target ads. But this has given the tech giants another big advantage: they have direct relationships with consumers that use their products, allowing them to ask for consent directly from a much larger pool of individuals. GDPR has handed power to the big platforms because they have the ability to collect and process the data. It has entrenched the interests of the incumbent, and made it harder for smaller ad-tech companies, who ironically tend to be European. In the longer term, however, it remains to be seen whether the law will ever force a substantial change in Google’s or Facebook’s business model in a way that could loosen their grip on the digital ad market.

I’ll discuss this in more detail next week. I produced a primer for my media clients on how the Google-dominated programmatic ads world works, and Facebook’s system. It needs to be edited a bit (read: clients paid $€ for the juicy bits so I cannot share everything). Theoretically more open than Facebook’s walled garden, but actually rigged in subtle ways to assure Google’s dominance. Some might say GDPR has (gasp!😱) …. reinforced the Google/Facebook duopoly. It’s an examination of how the GDPR works/doesn’t work in the real world. The problem with most GDPR presentations at legal and tech conferences is that they are too abstract.

And so GDPR came into being, lauded as a model for the United States and other nations struggling to find effective limits on data collection by technology companies. There was little doubt that, given the breadth of the law and the many suspected violations by global tech firms, there would soon be heavy fines or, at least, sanctions that would force Big Tech to change its operating methods.

But that promise has not been fulfilled. Aside from a €50 million fine that France’s privacy regulator imposed, there have been no fines or remedies levied at a U.S. giant since the GDPR came into effect. And the two nations most directly responsible for policing the tech sector – Ireland and Luxembourg, where the largest tech firms have their European headquarters – have yet to wrap up a single investigation of any magnitude concerning a U.S. firm.

Now the Irish regulator which oversees Google, Facebook, Microsoft and Twitter, among other giants, says that its first decision will not be delivered until … well, they do not know. Maybe 2021? They are dealing with so many COVID-19 related issues it is hard to tell.

But a few nuggets from yesterday’s GDPR Zoom chat:

• Probes take time because the GDPR is completely untested and cases need to stand up to the scrutiny of all 27 EU nations, as well as in national court. Big Tech has the financial power to execute the long game. You’re going to see a battle over fines and remedies in arguments that could take years to untangle, and which will only get resolved by the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg.

• Ireland and Luxembourg have faced special scrutiny because so many U.S. tech companies have set up shop in those tiny nations, which have actively courted them thanks to a mix of low corporate tax rates and business-friendly regulation. Those close relationships have created a strong degree of economic dependency, particularly in the Irish cases, which raises questions as to whether these countries are best suited to regulating Big Tech.

• The German are flexing their muscle. It is not on their agenda (on 1 June, Germany will assume the presidency in the Council of the European Union and will thus guide consultations in the bodies of the Council for six months). But German data privacy regulators are speaking their minds. The current “one-stop-shop” system, in which most major investigations are carried out by authorities in the country where the company is resident (most are in Ireland and Luxembourg), creates serious bottlenecks and an “unsatisfactory” situation for millions of web users. And the “one-stop-shop” system was the most heavily lobbied element by the Big Tech lobby brigade. Said one German regulator: “It is absolutely unsatisfactory to see that the biggest alleged data protection violations of the last 15 months with millions of individuals concerned are far away from being sanctioned.” Response from the Irish and Luxembourg regulators: “these delays have to do with the complexity of enforcing a new law.”

• Lead supervisory authorities, being overwhelmed, have leaned heavily toward “engagement” – or doling out advice on how to stay legal – over investigations and enforcement, to look busy. Or as one regulator told me “we’ll go after small companies, the low-hanging fruit, because we can force them to settle quickly”.

• There is a complete lack of transparency and cooperation between European data protection authorities that are meant to work hand-in-hand to enforce the rules, but end up being stymied by divergent national legal systems, cultural differences and an outmoded information exchange system.

• Worse, there are increasingly glaring differences in how EU watchdogs are interpreting the rules and, at times, breaking out of the one-stop-shop system to create what resembles a patchwork of privacy regimens instead of a single European landscape.

• And, the irony. After plenty of crowing about Europe’s comprehensive approach to privacy, it’s in the United States, where regulators have hit Facebook with a $5 billion fine over the Cambridge Analytica scandal, that enforcement has been the quickest on privacy. Yes, a mere pittance for the Facebook check book, but still. Europe has great laws on paper. But where are the enforcements? Where’s the beef?

And now .. COVID-19. The UK may have set the trend. It’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) has once again deferred massive GDPR fines issued to British Airways and Marriott International nine months ago. The fines, relating to data breaches that occurred during 2018, are not insignificant in nature: £183 million for British Airways and £99 million for Marriott International. Given that the ICO has a six-month period following a statement of intent to actually issue the penalty notice to demand payment, and there has already been a three-month deferment in January, this might seem like odd behavior.

However, investigations by the ICO are still ongoing and the current COVID-19 pandemic has certainly added fuel to the regulatory process. Not least when it comes to the ability to pay, allowing for the fact that the air travel and hospitality sectors have been particularly hard-hit by global lockdowns. Could these extensions, while perfectly understandable in the current unprecedented times we all find ourselves in, have a broader long term impact when it comes to GDPR enforcement generally?

Well, yes. A staffer at the ICO told me the view is “let’s get some perspective on all of this. What is the fair approach right now? Our internal discussions were pretty much along the lines that we were neither excusing nor negating their actions. Yes, we still need to hold those accountable for bad practices.”

The feeling in Brussels is mutual. A source at DG COMP (the department for competition responsible for the EU Commission’s policies on competition and antitrust law) said “the perceived risk of fines for businesses which are non-compliant with GDPR or who suffer a data breach is certainly going to diminish for a while. We really do not want to apply further financial penalties on businesses already dealing with the hit from the Coronavirus crisis on the economy. Obviously, we are going to consider the ‘ability to pay” factor.”

Several law firm counsel I have spoken with have said they already see many appeals for extensions granted primarily due to the financial impact of COVID-19. Whether “absence of actions” will lessen the effectiveness of the GDPR remains to be seen. And whether such flexibility sets a precedent remains to be seen.

No, the postponements do not defer the requirement for companies to ensure that information is stored and processed using the safeguards and controls that GDPR mandates. And while it’s easy to focus on fines, it is just one of the many options available to supervisory authorities. One source told me to expect to see more “warnings and reprimands”. Also, as I thumbed through the GDPR there is alway imposing a temporary or permanent ban on data processing, or suspending data transfers to third countries.

Note: one source told me there is also talk of “forgiveness” and flexibility due to Big Tech’ s help in the COVID-19 crisis. THAT requires a separate post 🙂

As most readers know, I am a GDPR cynic. So will these extensions likely have any real impact on the future of data protection, data security and data governance, especially as we emerge from COVID-19 lockdown into what is likely to be a prolonged recession? Keeping customer data safe and investing in data governance won’t go away during this crisis and any associated recession.

But as I have noted before, stick a few million software engineers in quarantine who have had a lot of time to think and tinker and … BANG! There they are, cooped up at home, getting frustrated with their current tools or platforms and wondering if they can spot some pain point, or mechanic, or small difference to the flow … and they go and create or solve some opportunity that no-one ever quite realized was there. And more importantly, many have focused on:

• How to force their employers to prioritize data security

• What tools can they employ to help their employers really understand their data better

• And the biggie: how best to help them know what they’ve got and where it’s stored in order to find the asset value will help to rebuild and define competitive advantage in extremely tough trading conditions, not just legal compliance issues

Much of that is GDPR related but most of it just good business sense.