[ Pour la version française, veuillez cliquer ici ]

[ Für die deutsche Version klicken Sie hier ]

26 March 2020 (Brussels, Belgium) – The feeling that civilization might end is only discussed amongst a few. And it is probably way too extreme, even for a cynic like me. My American and European cohorts have a blind assumption of relative stability. Shit’s been feeling a bit crazy, but that fear of not knowing what tomorrow could look like has not been there, at least in my lifetime.

And my daily routine has some added elements. I bleach my incoming hard copy post deliveries, I wear surgical gloves at the grocery store, I am ever vigilant over my space between fellow humans (and walking through their spaces) worried about transmission via “droplet spread”. And I bought 100 cans of tuna and 50 packages of Orville Redenbacher popcorn.

But I still read my travel websites. Yes, all have a somber tone, each of us arriving at a sheltering in place, canceling our plans and making preparations to stay home indefinitely. But the stories I read now are not invitations to travel. At a moment when borders are closing and travel is mostly forbidden, these stories read like dispatches from a world that we did not fully appreciate, one in which we were free to move around the globe.

And I watch my neighbours become remote workers, and homeschoolers – all at once. Mass school closures have meant that many new remote workers face the competing challenges of full-time work and full-time childcare.

It has led to scores of “Remote Control” workshops where parents will get expert advice on managing multiple tasks and warding off chaos. But the kids are having some fun:

The COVID-19 pandemic: a challenge that has been perfectly crafted to feed on our every societal and informational weakness. From the American perspective, health insurance, inequality, federalism, leadership, Trump, individualism, social media, broadcast media; all the shortcomings of every one of those elements feel built to exacerbate this crisis. I listen to Trump who says:

“Our country wasn’t built to be shut down. Because we built this city on rock and roll”.

Or something like that. And I wonder when Trump will stop appearing at the White House daily briefings. Soon, I imagine. When the hospitals are flooded across the country, and the bodies pile up. For now these daily briefings of his are a primary narcissistic supply source. As the toll rises from Trump’s horrific failure, the briefings will become a source of narcissistic injury. He’ll need to withdraw. And, Jesus. I am actually reading the academic literature on narcissism. Amazing times that political coverage requires that knowledge.

Cable news? A joke. Giving Trump free airtime. It’s a repeat of 2016 all over again. Joe Biden? He’s worried about getting the lighting right in his living room to make an address. Or Zoom. But more about America in a bit.

This enemy has no side. And whatever/whoever it’s been, there was always a very clear character that brought you grief. That’s how our reality show works. It’s maddening, but we’ve all learned to process everything like this. This coronavirus is clearly none of the above. There is no “us” versus “them”. And we are troubled, depressed, confused. We want constant updates. We need a constant flow of new information. It’s how everything has wired us over the past few decades. We’re exploring the charts and reading the posts. We can find something new every minute of every one of these days, yet, none of it really makes a difference. But, we’re sitting at home and need those dopamine fixes, even more, to get us through the day. We are not patient. We need an answer and an update … NOW!

And I work my way through the twisted paradoxes. Because it is a time of paradoxes and contradictions. The coronavirus leaps out of some animal into some reservoir host, across into humans, through world markets, and gets spread by our most dynamic bits of modernity. That’s a paradox. It’s tiny, 120 nanometers. It brings down the world economy, which is one of the biggest things that we know. That’s a paradox. And then, there’s this paradox: we need to act collectively, but we also need to take individual personal responsibility. So it really is very much a strange time of paradoxes that we’re trying to navigate.

Yes, yes, yes. A tsunami of material to read. When I started my Coronavirus series (that is the only link in this post; you can easily find on Linkedin and Twitter all the people I mention, and all the articles are an easy Google search) I thought I would be overwhelmed. And God, the complexity! The unprecedented uncertainty amid the coronavirus pandemic has decimated our carefully laid plans and unsettled our minds at equal pace. Anxiety manifests in an utter inability to concentrate; our efforts to “work from home” are largely consumed by staring blankly at Twitter, the homepages of La Repubblica, Le Monde, the New York Times, the Guardian, Süddeutsche Zeitung, and Medium posts stuffed with impenetrable graphs and dubious advice.

This coronavirus, with its health, social, scientific and economic impacts, has made the content production engine of this world go into overdrive, leaving most of us struggling within an infodemic. Unreliable information is also adding to anxiety as it ultimately leads to contradictions, doubts, and lack of trust.

But I soon realized I was prepared. Edgar Morin, the French philosopher and sociologist who has been internationally recognized for his work on complexity and “complex thought” (pensée complexe), whom I often quote, said in his book Introduction à la pensée complexe:

Reality is vast. It will soon far surpass the scope of our intelligence. Will it be possible to recognize our abysmal ignorance?

We have entered in age of atomised and labyrinthine knowledge. Many of us are forced to lay claim only to competence in partial, local, limited domains. We get stuck in multiple affiliations, plural identities, modest reason, fractal logic, and complex networks.

But most of us do not get stuck, and right now we cannot get stuck. Yes, a difficult as it is, we must be interdisciplinary. We must focus. We must take all those pieces, shards, ostraca, palimpsests, barrage of news clips and web sites screaming by us and determine what we think is key to know and internalize it.

I do. And the result? Eh, another way too long blog post from me. But that’s how I can internalize everything I am reading/learning about this coronavirus. We have created an environment which rewards simplicity and shortness, which punishes complexity and depth. I hate it. The model I try to follow is like the British magazine tradition of a weekly diary – on the issue, detailed, but a little distant from it, personal as well as political, conversational more than formal.

This coronavirus has forced us (once again) to see that there really is no division between the “hard” sciences” and the “soft” sciences. Our move to take traditional disciplines and fragment them into 1000 autonomous domains was/is misguided. To understand, to cope with this coronavirus and what will become the “new normal” we need to deal with the complexity of this new territory. We are forced to become interdisciplinary. Another French philosopher, Marcel Gauchet, has also written about this:

Specialization, fragmentation of knowledge will resoundingly lead to superficial generalization by the media, and everyone will be fixed in fragmented competencies. It will lead to the entrenchment of the elites and it will lead to universal ignorance and most probably universal corruption, that will lead to a populism with all of its aberrations.

He wrote that in the 1980s. Fodder for another post.

Yes. For most of time, Earth was a safe and stable home for our world. Well, ok. Not quite. As Dr. Chris Donegan corrected me (a chap who tags himself on Linkedin as a “Skeptical Empiricist”, who keeps my posts honest, and who has a day job as a seasoned investor and advisor focused on IP-rich private companies) :

But over the last century, our world has been advancing exponentially in technology but remaining stagnant in wisdom. We are rapidly gaining tremendous powers but still behaving like short-sighted primates. The voice of wisdom is there, but it’s being trampled over by political parties, religions, and nations too mired in blind conflict to lift their heads up and see the bigger picture. Our world is so, so stubborn about growing up.

This is not a black swan. This pandemic was predictable. As Azeem Azhar noted this week in one of his stupendous blog posts, many terms can be used to describe the Covid-19 pandemic. Virulent. It has been, spreading to 475,052 people (as he typed that) spreading faster than SARS. Unprecedented in its economic impact? Certainly. It has delivered the deepest, fastest economic shock in history, according to Nouriel Roubini in a link I posted earlier this week:

Earlier this month, it took only 15 days for the US stock market to plummet into bear territory (a 20% decline from its peak) – the fastest such decline ever. Now, markets are down 35%, credit markets have seized up and credit spreads (like those for junk bonds) have spiked to 2008 levels. Even mainstream financial firms such as Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley expect US GDP to fall by an annualised rate of 6% in the first quarter and by 24% to 30% in the second. The US Treasury secretary, Steve Mnuchin, has warned that the unemployment rate could skyrocket to above 20% (twice the peak level during the financial crisis).

In other words, every component of aggregate demand – consumption, capital spending, exports – is in unprecedented freefall. While most self-serving commentators have been anticipating a V-shaped downturn – with output falling sharply for one quarter and then rapidly recovering the next – it should now be clear that the Covid-19 crisis is something else entirely.

But there is one thing that it certainly isn’t. It isn’t a Black Swan event. As Azeem points out, as defined by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, a Black Swan event is an extreme, unforecastable, rare event, a genuine “no-one could predict this” occurrence:

[A]n event with the following three attributes.

First, it is an outlier, as it lies outside the realm of regular expectations, because nothing in the past can convincingly point to its possibility. Second, it carries an extreme ‘impact’. Third, in spite of its outlier status, human nature makes us concoct explanations for its occurrence after the fact, making it explainable and predictable.

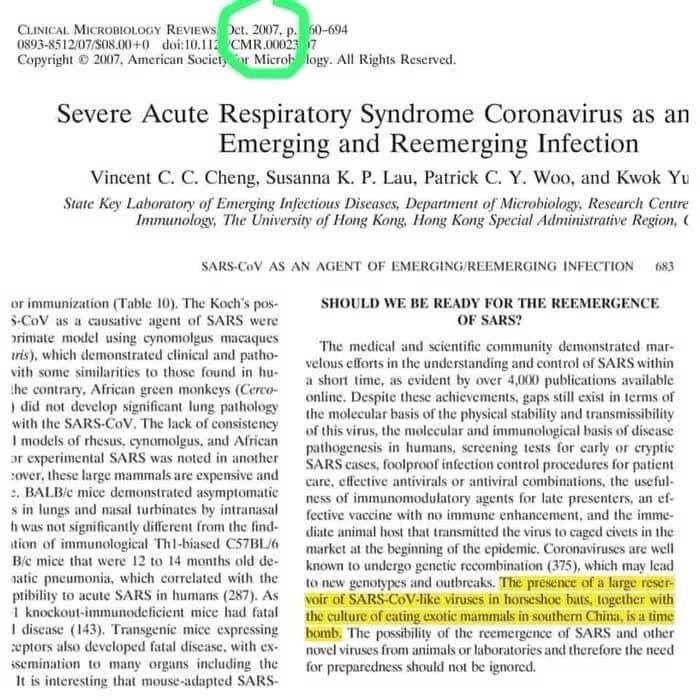

This was predictable and predicted. Bill Gates danced around the idea four years ago but with a level of generality. But some were dealing with it at a very specific level of detail. The paper everybody is pointing at is this one (hat tip to Vishal Gulati for spreading the word and Azeem for dedicating a post to it). Note the date:

As Vishal noted in a Tweet:

This is not just 1 paper addressing it. There are 1000s of such papers on this very risk every year. And we have had 4 such textbook recent outbreaks: SARS, MERS, Ebola, H1N1

Indeed, Taleb concurs:

such a global pandemic is explicitly presented there as a white swan: something that would eventually take place with great certainty. Such acute pandemic is unavoidable, the result of the structure of the modern world; and its economic consequences would be compounded because of the increased connectivity and overoptimization.

As a matter of fact, the government of Singapore […] was prepared for such an eventuality with a precise plan since as early as 2010. Even at times of this, analysis and specificity, matter. The responses we make today, fire-fighting and battlefield triage, are essential until we get on top of this pandemic. But what happens afterwards, the decisions we take to shape the future, are also vital. Understanding how the major parties in our economies (governments, investors, corporations, boards) prepare for a predictable event is a critical piece of the puzzle.

As many have written, the U.S.’ broken healthcare system is why the coronavirus is set to explode in America. It is a system built and based on profit and not service.

The United States, long accustomed to thinking of itself as the best, most efficient, and most technologically advanced society in the world, is about to be proved an unclothed emperor. When human life is in peril, it is not as good as Singapore, as South Korea, as Germany. The problem is not that it is behind technologically. The problem is that American bureaucracies, and the antiquated, hidebound, unloved federal government of which they are part, are no longer up to the job of coping with the kinds of challenges that face us in the 21st century. Global pandemics, cyberwarfare, information warfare — these are threats that require highly motivated, highly educated bureaucrats; a national health-care system that covers the entire population; public schools that train students to think both deeply and flexibly; and much more.

Too much to detail to discuss in this post so just a few points:

1. This story has been told repeatedly — and correctly — as an illustration of what’s wrong with the Chinese system: The secrecy and mania for control inside the Communist Party lost the government many days during which it could have put a better coronavirus plan into place.

2. The United States also had an early warning of the new virus — but it, too, suppressed that information. In late January, just as instances of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, began to appear in the United States, an infectious-disease specialist in Seattle, Helen Y. Chu, realized that she had a way to monitor its presence. She had been collecting nasal swabs from people in and around Seattle as part of a flu study, and proposed checking them for the new virus. State and federal officials rejected that idea, citing privacy concerns and throwing up bureaucratic obstacles related to lab licenses.

3. Donald Trump, just like the officials in Wuhan, was concerned about the numbers — the optics of how a pandemic looks. And everybody around him knew it. Alex Azar, the former pharmaceutical-industry executive and lobbyist who heads the Department of Health and Human Services, was not keen on telling the president things he did not want to hear. There are lots, and lots and lots of media stories on this.

4. Without the threats and violence of the Chinese system, in other words, we have the same results: scientists not allowed to do their job; public-health officials not pushing for aggressive testing; preparedness delayed, all because too many people feared that it might damage the political prospects of the leader.

So now Americans wake up to the news that hospitals must consider universal do-not-resuscitate orders for coronavirus patients. They worry that “all hands” responses may expose doctors and nurses to infection, prompting a debate about prioritizing the survival of the many over the one. And stuff like the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommending live-streaming funeral services to cut down on exposure to the virus.

Unless they are over 85 .. ok, or queer, or Black, or Native American, or Middle Eastern American, or Asian American, or Jewish, or Latinx, or poor, or homeless, or addicted … Americans don’t have the capacity to imagine mass casualties of people like themselves. We … white Americans, and though I am no longer a U.S. citizen I classify myself as “American”. Well, and Greek … are selfish and ignorant. Most in the U.S. are not following social distancing orders. Students with faces the color of uncooked pie dough say they deserve their spring break in Florida and they’re gonna take it. People who don’t watch the news or watch the wrong news crowd the dollar stores, loading up on stuff. They deserve their stuff and they’re gonna take it. On the other end of the stepladder, where narcissism collides with opportunism and makes a baby, Trump wants to reopen the economy. What’s a few million lives shaved off the bottom. The old, the infirm, the poor. Two birds, one stone.

The richest country in the world and all I read about are hospitals running out of Propofol (the most useful sedative for ventilated patients, by the way), and Hydroxychloroquine being rationed. And Vitamin C in limited supplies, and other outpatient meds running the risk of being depleted. And normal floor beds were converted to ICU beds on the fly as a cascade of patients require emergent intubation. And yet, and yet it is absolutely inspiring to watch RN, NP/PA and MD administration come together to find a way to care for these patients.

In Italy it is pretty much the same. How could this happen in one of the best health care systems in the world? As Paola Bonomo has noted:

It is true that Italy has one of the best health care systems in the world. For those who suffer from cancer, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome etc. – all of which are non-communicable diseases – the “big killers” of the last 50 years, Italy is among the best places in the world to get health care and live a long life.

But this is not true for highly infectious diseases, for which – as many Italian doctors said – the approach must be community-centered, not patient-centered. And this may be the reason why China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Japan acted so swiftly and (after initial delay in China) successfully: because in their culture the community has always come before the individual.

On the other hand, in the UK and in the U.S. and in the West in general the individual comes first. So, to me, all this chatter about “the community” and “we must come together” is wasted breath. It is not in our DNA.

Yes, yes, yes. It’s becoming increasingly clear that the best thing we could’ve done is shut everything down a few months ago. But could you imagine the panic and rage that would’ve incited? One of the most dangerous parts of this “what if” imposition of draconian measures early on … what if nothing happened? Then everyone who doubted those measures would feel proven right. It would be a polarised field day worse than the one being played now. Yes, we have the data on South Korea versus Italy, but that is not how our politics or society work any longer. That is not how our leaders operate today.

Because … NEWS ALERT!! …. containing, or suppressing an outbreak, has no surrender ceremony. The victory is in the silence, in the lack of something happening. Think about the decision calculus for a Western leader: if I shut everything down and am right, then nothing happens and everyone blames me for shutting everything down. If I don’t shut things down, and that was the wrong decision, the cases will begin to explode, and then we will all collectively demand a shutdown. That is an almost impossible calculus for an elected Western official. Essentially, it calls for self-sacrifice, because just imagine the backlash on the first scenario. There has to be some logic term for this decision calculus, right? Maybe. But not in America.

One of these days I will write an essay, a post-plague epic about American ignorance.

And there will be changes on how we embrace technology in the future, wonderfully discussed in a very long thread on Linkedin started by Martin Nikel. Plus Debbie Reynolds who posted on Linkedin a piece in Fortune Magazine by Robert Wolcott wherein he discusses how the Coronavirus has shown that those who do not properly employ technology will create a separation between those who win and those who lose in business from now on. His lead paragraph:

When Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon River with his army in January, 49 BCE, he violated a centuries old stricture, effectively declaring war on the Roman Senate. Everyone with Caesar that day knew they’d either emerge victors or vanquished.

With COVID19, we’ve all crossed the Digital Rubicon. The current crisis should eliminate any uncertainty about the wisdom and urgency of fundamental digital transformation.

Through this pandemic, digitally savvy organizations are shifting faster how they work, produce, serve and protect. Companies enabling these transitions have been rare performers on collapsing equities markets, such as Zoom, ZScaler and Crowdstrike.

Agreed. But I still need to grapple with the fact the extent of our shared trauma has yet to materialize so “business” and “stakeholders” and “digital technology/digitisation” are not yet front and center in my mind.

I am still struggling with this stuff. I have much to learn. This essay with be modified over time. But so far all the complex/interlocking dynamics exposed show a basic absurdity at the heart of our global society. It is not a system aimed at satisfying our desires and needs, at providing humans with greater amounts of physical utility. It is instead governed by impersonal pressures to turn goods into value, to constantly make, sell, buy, and consume commodities in an endless spiral and ignoring the effect of that system on the “normal human”.

Because containing the spread of the coronavirus is about more than practicing good hygiene. On trial is a whole global system of profiteering and its structural laws and incentives. What the pandemic has revealed is not just that companies are out to get rich – a story as old as time – but specifically our unprecedented degree of global interdependence in the year 2020.

The coronavirus seeks only to replicate. We seek to halt that replication. Unlike the virus, humans make choices. This pandemic will pass into history. But the way in which it passes will shape the world it leaves behind. It is the first such pandemic for a century. And it comes to a world that — unlike in 1918, when the Spanish flu hit — has been at peace and enjoys unprecedented wealth. We should be able to manage it well. If we do not do so, this will be a turning point for the worse. Making the right decisions requires that we understand the options and their moral implications.

I am a realist and I am a cynic. To me that means we’ll need to decide who will bear the costs of those choices – and how.

Not so fast. In fact, safety and stability are post WW2 illusions created by Western style public health measures, vaccination and penicillin. The norm of life is “nasty brutish and short” to paraphrase Hobbes. As for complexity: one thing that everyone learns when they go down the PhD rabbit hole of science specialism is that the more they learn the greater their awareness becomes of their own ignorance. The current fantasy of AI as a panacea to big data rich problems is a continuation of the delusion. The governments of most developed nations formed their models in the 18th or 19th centuries. Very few are fit for purpose in the 21st. But bureaucracies don’t simplify themselves.