20 March 2020 (Brussels, BE) – Telemedicine has never looked so useful. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has people scared, sick, and stuck at home under government orders, the ability to remotely handle routine care or offer advice as to whether or not someone should get tested for the coronavirus is priceless. This is a theme in other industries, too. Martin Nikel, a leading light in the legal technology community, started a Linkedin thread of how COVID-19 could have an instant effect on the adoption of remote technology in law and legal services.

But as we push to take more diagnostics and consultations remote, we need to make sure the devices we use and the security and data protocols we advance are eventually vetted and considered. This post is going out to my entire TMT (telecommunications, media, and technology) and cyber security communities so they are well aware of these issues.

Already governments are trying to help promote telemedicine. For example, in the U.S., there is a move to alleviate HIPPA requirements on video calls so doctors can use Skype, FaceTime, and other popular conferencing systems as opposed to a dedicated (and expensive) telemedicine setup. European governments are doing the same vis-a-vis their data protection requirements.

Other elements we’ll need to consider are how to bill for telemedicine consultations, and what tools doctors can rely on to help get vital signs or monitor patients. Fodder for another post.

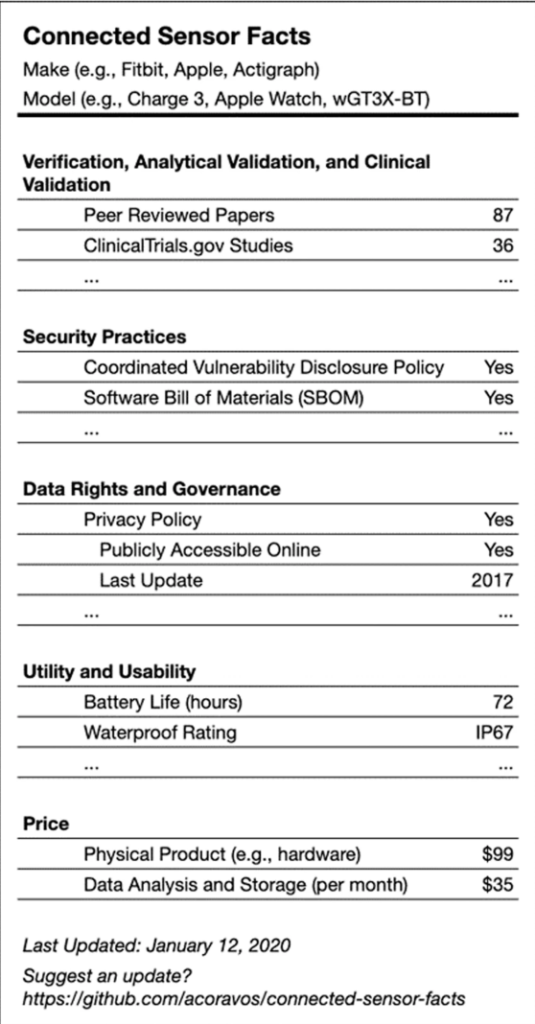

A suggested label for medical devices that gives both users and prescribers important information. Image taken from the “Nature” article noted below.

The connected devices that can act as diagnostic tools are the focus of an article in the journal Nature that was written by several people at the forefront of connected medicine, two of whom I know. The article tries to establish a framework for secure, usable, and trusted connected devices for deployment in a home or remote setting. Because one way or another, we’re going to emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic with a new model for health care delivery that includes connected devices in the home and remote monitoring, and we should act now to get it right.

Andy Coravos, CEO of Elektra Labs and one of the article’s authors, says the group has been working on the paper for more than a year, and in some ways wished its publication didn’t coincide so directly with COVID-19 because readers might view it as something more for the long term, as opposed to an immediate need.

And you can guess the reaction. People think “the focus should be on just getting remote monitoring and telemedicine tools in place, with verification, privacy, and data security coming later!” However, Coravos makes a compelling case for doing all of it now:

“This is an immediate need because one of the fallacies coming out of Silicon Valley is regulations slow innovation, but good regulation and policies are a precondition for innovation because if people don’t trust the system, they won’t try the system.”

In other words, focusing on privacy and demanding security now will save us later on.

The Nature article lays the groundwork for making sure that remote care will be reliable, secure, and private. So let’s take a look at what the group proposes. The overarching idea is that devices would need to be reviewed by professionals for consistency and clinically relevant data, while also having been designed with security in mind and in a manner that respects user privacy.

The proposed framework has five aspects:

1. Clinical validation: Does the device measure what it claims to measure and is it relevant to the target population?

2. Security: Is the product designed securely? Is there a software bill of materials? What is the disclosure policy?

3. Data Rights and Governance: Who has access to the data gathered by the device and when? Can users find an easy-to-understand privacy policy?

4. Utility and Usability: How is the tool worn or used? What is the battery life? Is there tech support?

5. Economic Feasibility: What is the net benefit vs. the cost of the device? Is that a onetime fee, or the cost of a subscription?

Obviously, this is a lot of data to gather and convey, which is why the authors of the article posted the above image of a nutrition-style label for devices. Nor would every device need to adhere to the highest standards for every item on this list. A thermometer is very different than a machine designed to detect a person’s level of insulin and auto-inject it when their blood sugar is low, for example.

But there are some important subtleties. For example, when dealing with machine learning algorithms, especially on devices that will attempt to auto-correct a medical issue or auto-diagnose a problem, understanding how the machine learning algorithm was developed would be essential. This should be part of the validation phase, and could include steps such as sharing the data sets used and how they were annotated.

One of the core ideas underlying the inclusion of the security and data privacy elements these authors are proposing is that while all connected devices can experience security failures, those failures don’t have to cause harm. Another is that, when it comes to devices that might directly affect a patient’s well-being, there should be higher standards in place when it comes to testing their security and vulnerability. Similarly, understanding what data gets shared is worth thinking about in the event that such data is compromised.

The framework’s fourth point, about usability, would have repercussions for both the patients trying to use a device and how the data from the device would fit into the physician’s or hospital’s workflow. I’ve had conversations with several doctors who were leery of connected devices because they ended up having to troubleshoot and provide tech support for their patients. They are also worried about a deluge of irrelevant data.

There’s currently a challenge around bringing data from connected medical products into existing hospital software and patient medical records. There are open standards, such as the Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources, or FHIR (pronounced fire), standard, but most medical practices and hospitals are still stuck integrating data by hand or at the will of their major medical records software provider. Obviously, efforts to let patient data flow more seamlessly would help boost the usability of connected sensor data, but that ease of use would also open up risks around security and data loss if such precautions weren’t taken.

The authors don’t spent a lot of time on the issue of economic feasibility, in part because it’s such a complex area. But they do point out that economic feasibility in health care will be spread among a variety of entities, including insurance companies, hospitals, and consumers. One person’s advantage might be another’s cost, something most U.S. doctors and consumers are already familiar with from dealing with their insurance carriers. Plus, benefits can’t always be valued in economic terms, another problem that we deal with in health care all the time.

There’s a lot more to discuss in this article, but the basics are worth bringing up with consumers, doctors, and policymakers as we embark on a new era of health care delivery. We need to move fast, but as the authors make clear, we can still avoid breaking things.