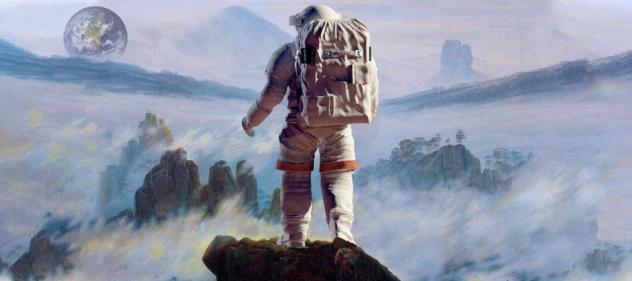

(my thanks to Caspar David Friedrich)

(my thanks to Caspar David Friedrich)

– with a postscript: books I highly recommend for a deep dive into the U.S. space program

[ for my companion piece “Moon on the mind: two millennia of lunar literature” please click here ]

20 July 2019 (somewhere on the Mediterranean Sea) – Could it be that everyone is so moved by the Apollo moon-landing anniversary this weekend because we’re all desperate for a grand common project – something more heroic and uplifting than calling people out on Twitter, FaceApping, and designing even *better* ad-tech software?

Maybe it’s the declining political terrain. This past Tuesday also marked the 20th anniversary of the death of John F. Kennedy, Jr., his wife Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy and sister in law, Lauren Bessette in a tragic plane accident near Martha’s Vineyard. His father launched us on this space effort. What strikes me most now, that didn’t then, is John Kennedy Jr.’s foresight into what politics was morphing into if we did not pay attention – an entertainment front. So maybe Apollo is a dream of “past glory” because we hate the present, seeing ourselves spiraling forever downward to a destiny foretold.

The Apollo space program was the capstone of an era in which Americans took it for granted that the federal government could and should solve big challenges. It was one of America’s defining moments. Engineering, heros and awe – all in one package. The Apollo program that took humans to the Moon is properly viewed as an outgrowth of the cold war between the United States and the Soviet Union. (I’ll address more of the history at the end of this post when I review several “must read/should read” books on the U.S. space adventure).

But not since then has the U.S. tried something as ambitious or as expensive. Yes, Americans still take risks and solve problems, but they don’t look to the federal government to do it. Back then, the federal government, enmeshed in the space race and Cold War, spent twice as much as private business on R&D. Today, business spends three times as much as the federal government. We now equate risk-taking and innovation not with moonshots, but with venture capitalists, pharmaceutical labs and internet entrepreneurs.

Yes, Presidents still invoke the spirit of Apollo (President Obama called for an Apollo-scale investment in renewable energy and a “moonshot” to cure cancer; President Trump has said he wants to return to the moon, and then go to Mars).

But as Greg Ip, Science editor for the Wall Street Journal, noted on his blog last weekend:

These grand visions lack Apollo’s unifying motivation of the Cold War, the clarity of its target, and the New Deal faith in big, ambitious government. The intensifying U.S. rivalry with China is sometimes called a new Cold War, but it’s being waged with private investment such as in 5G telecom networks, not public projects.

Yep. We can solve ‘X’ – provided it is a technical challenge. But you need to throw money at it and manage how it is spent properly. But today more of our problems are social – and you can’t solve social problems that way.

My own lunar dreams

Night sky over my house in Greece, shot by photog friend Panos Euripiotis

My Greek island is what you expect the earth to look like if it was given a fair chance. It is not mysterious or impenetrable, but awesome – made of earth, air, fire and water. Yes, it changes seasonally with harmonious undulating rhythms. It breathes. Here you can get a bit nearer to the stars and the ether. It is where I came as a child (and now as an adult) to feel the earth, feel space.

It started as a kid growing up in New York City, my delight being the trips we made to an aunt and uncle who lived in Florida near Cape Canaveral which was the location of NASA’s launch complex. My uncle worked there and often got me into the facilities. It was a wonder. I watched many a launch, live, and got to meet space scientists and engineers and even a few astronauts-in-training.

Some brief history: on November 28, 1963 President Lyndon Johnson announced in a televised address that Cape Canaveral would be renamed Cape Kennedy in memory of President John F. Kennedy, who was assassinated six days earlier. The name change was not popular in Florida from the outset, especially in the bordering city of Cape Canaveral. In 1973, the Florida Legislature passed a law restoring the former 400-year-old name. The Kennedy family issued a letter and said it was a matter to be decided by the citizens of Florida and they understood the decision. The family was pleased NASA’s Kennedy Space Center retained the “Kennedy” name. The Gemini, Apollo, and first Skylab missions were all launched from “Cape Kennedy.” The first manned launch under the restored name of “Cape Canaveral” was the final Skylab mission, on November 16, 1973.

I became fascinated by astronomy, going through a series of telescopes and making multiple visits to planetariums and observatories around the U.S., and eventually across Europe. It resulted in my completing a minor in physics at university.

The passion continued. I followed with delight the European Space Agency launch of Rosetta, with Philae, its lander module, and its subsequent landing on a comet 10 years later. ROSETTA! IMAGINE! A space vehicle launched in March 2004 … with technology on board that had been developed in 1999 and 2000 (space technology usually takes 4-5 years of testing until proven before put on board a spacecraft). It then landed, as planned, 10 years later – with 92% of its technology working.

My fascination continues to this day. In one of my visits to CERN in Geneva (home to the Large Hadron Collider), I attended sessions to learn how to write computer code to track planets and stars … and to learn the basics of observatory science. Every year at the world’s largest industrial fair, the Hannover Messe, CERN and the European Space Agency always present wondrous technologies they have developed, many that could find applications in space.

Oh, the sublime Romanticism of the moon landing – and its reality

The first lunar landing was many things — a D-Day-like feat of planning and logistics, a testament to the power of man’s will, an ostensible propaganda coup for the West. But it was also a misunderstood event. In practical terms Apollo 11 was meaningless. It was a voyage undertaken for no meaningful scientific purpose. (This was more widely acknowledged in the years leading up to the mission than it is today.) Practically nothing of value was obtained from putting a man on the moon that could not have been just as easily acquired by a robot.

It was all ideological. When Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space on April 12, 1961, the newly inaugurated President Kennedy needed a way to reclaim leadership from the Soviet Union. He asked his vice president, Lyndon Johnson, to devise a space program that promised dramatic results, and that the U.S. could do first, according to John Logsdon in his book “Race to the Moon”:

The answer came back: “go to the moon.” On May 25, in a speech before Congress, Kennedy set a goal that before the decade was out, the U.S. would put a man on the moon and bring him home safely.

Kennedy never stopped worrying about the price, first pegged at up to $9 billion for the first five years. He suggested to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev that they combine efforts to defray the cost. Khrushchev demurred. Liberals complained that the money could be better spent on anti-poverty programs, conservatives that it should go to defense. Yet for Congress, at least initially, price was no object. The U.S. budget was in rough balance and the Soviet lead in space was viewed as an existential threat.

No one believed this more fervently than Johnson, as Senate majority leader, vice president and then president. In his memo to Kennedy advocating a lunar landing, Johnson wrote: “If we do not make the strong effort now, the time will soon be reached when the margin of control over space and over men’s minds through space accomplishments will have swung so far on the Russian side that we will not be able to catch up, let alone assume leadership.”

Johnson embodied the New Deal ethos that the federal government could, and should, accomplish big things, as it had with the Tennessee Valley Authority and Grand Coulee dam during the Depression, the Manhattan Project during World War II, and the Interstate Highway System starting in the 1950s. Says Roger Launius in his book “Apollo and the Great Society”:

Johnson, a New Dealer, viewed the Great Society as an extension of that, and Apollo as part of the Great Society. The space program would have economic benefits. Huntsville, Alabama and Houston, Texas are space hubs thanks to Johnson’s use of space as a spur to Southern economic development. NASA outsourced much of Apollo’s development to private contractors, which both earned the program support and spread its benefits. Technology developed for the space program spurred advances in computers, miniaturization and software, and found its way into scratch-resistant lenses, heat-reflective emergency blankets and cordless appliances. It inspired thousands to pursue careers in science and technology. Doctorates awarded in engineering and physical sciences tripled from 1960 to 1973.

But it was, above all else, a triumph of our aesthetic instincts. It was the juxtaposition of man against a brutal environment upon which he could project his feelings of transcendence. Matthew Colin of The Week magazine noted on his blog:

The greatest historical analogue to the manned lunar mission is probably the early years of English polar exploration — those heady days when, as Francis Spufford argues, hard men put their will in the service of a literary mania for feelings of remoteness, hugeness, and brooding oceanic emptiness. What a shame that we have been able to produce no great lunar literature to succeed the writings by Byron, the Shelleys, Tennyson, and Melville that both immortalized and inspired the great hypothermic pioneers.

His point is you need to look at the Apollo 11 mission from the perspective of both the participants and the spectators. The lunar landing was not a scientific announcement or a political press conference; it was a performance, a literal space opera. It was brought together through the efforts of more than 400,000 people, performed before an audience of some 650 million. Yes, it was a victory of Western democratic capitalism over Soviet tyranny, but as Neil Armstrong himself said, it was also a victory for humanity.

All of this comes through in Oliver Morton’s book The Moon which I talk about in more detail below in my book reviews. The book ranges through science, history, politics, art, science fiction, speculation and more besides. Among contemporary observers in seeing the true significance of the lunar landing was Vladimir Nabokov, who rented a television set for the occasion. He wrote:

That gentle little minuet that despite their awkward suits the two men danced with such grace to the tune of lunar gravity was a lovely sight. So visual. It was also a moment when a flag means to one more than a flag usually does. What an absolutely overwhelming excitement of adventure, the strange sensual exhilaration of palpating those precious pebbles, of seeing our marbled globe in the black sky, of feeling along one’s spine the shiver and wonder of it.

I will think about that sublime happiness as this weekend I watch (for the hundredth time) what is perhaps the most unlikely piece of art ever created for the ennoblement of our species.

Cancer, climate, plastics: why ‘earthshots’ are harder than moonshots

If we can send a human to the Moon, why can’t we build sustainable cities? Defeat cancer? Tackle climate change? So go the rallying cries inspired by one of humanity’s greatest achievements. There’s no question that this mission was an extraordinary feat on NASA’s part. Challenged by President John F. Kennedy in 1961, the then-fledgling space agency went from having minimal experience with spaceflight — just Alan Shepard’s 15-minute suborbital hop — to designing, building and flying machines to take humans some 380,000 kilometres to another world and back. Yes, the Apollo programme was born during the cold war between the United States and the Soviet Union, but it ultimately transcended those politics and became a global triumph.

But you need perspective. Apollo drew on impressive financial and human resources. The U.S. government spent about US$26 billion — $264 billion today – on Apollo between 1960 and 1973. At its peak, the mission involved some 400,000 people, many of whom worked at the giant aerospace companies that helped to build the rockets and spacecraft. Together, they solved issues such as escaping low Earth orbit and choreographing safe trips to and from the lunar surface.

Fast-forward five decades, and the moonshot framework — defining a problem, supporting it with money and cross-disciplinary expertise and attempting to solve it in a given timeframe — is being applied to more-complex challenges that we might call “earthshots”. There are several such efforts in the United States to conquer cancer. The European Commission’s forthcoming €100-billion (US$112-billion) Horizon Europe research-funding programme — “inspired by the Apollo mission” — includes initiatives for cancer, climate change, oceans and soils. A Japanese moonshot announced in April doesn’t even have a defined target, although it might include eliminating plastic.

The appeal of the moonshot framework is understandable. Before Apollo, it worked for the Manhattan project. It worked for Green Revolution agriculture in the 1960s. And it worked for the Human Genome Project in the 1990s. But the latest efforts will be harder to achieve, in part because their predecessors didn’t have to face the same scale of corporate expectation. Take the urgent need to develop a new generation of antibiotics. This requires close cooperation between universities, companies, governments and other groups. But pharmaceutical companies are reluctant to invest unless they are likely to reap large profits, so progress is slow.

It is even worse in the case of climate change: for decades, energy corporations have stymied global efforts to make equitable reductions to greenhouse-gas emissions because such efforts would reduce their profits. Influential private companies are central to today’s earthshots, but the historical moonshot approach will be ineffective if potential conflicts of interest are not addressed.

There are other reasons, too, why a conventional moonshot would be less than ideal for approaching complex problems. Take the case of climate change. That will require not just money and expertise, but also reconciliation of competing political ideologies, especially in richer countries; satisfaction of demands for equity from poorer countries; and recognition of the citizen voice rising today in local campaigns such as climate strikes in schools.

But adapting the moonshot approach to fit modern earthshots should in no way detract from Apollo’s achievements. On the 40th anniversary of the Moon landing, Nature magazine had polled almost 800 scientists and found that the mission had inspired more than half of them to become scientists. That is a concrete example of how NASA shaped an entire generation of researchers.

As the world commemorates the epic feat of landing a person on the Moon, let us also celebrate how individuals came together, how they solved complicated and difficult problems and how they set aside individual interests to achieve collective success in what will always be one of humankind’s greatest accomplishments.

IN CONCLUSION …

We should not be seduced by the nostalgia of Apollo or the allure of “the Return” as we grapple with vast, multi-pronged challenges on Earth. Then-NASA administrator Thomas Paine recognized as much at the Apollo 11 launch, when he spoke to the activist Ralph Abernathy who had come to protest the Apollo program (more on that protest below). Paine later recalled admitting that compared with solving poverty, racism and other injustices, the “great technological advances of NASA were child’s play”.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Some propulsive reading

Buzz Aldrin steps off the Lunar Module to become the second person on the Moon on 21 July 1969

The photograph above is my favorite Apollo photo. It brims with meaning: Someone took it. Someone else was already there, is unseen but known to the viewer, and we are seeing this moment as he saw it. “A portrait is not made in the camera but on either side of it,” as the early-20th-century photographer Edward Steichen put it. A photo’s existence implies the photographer’s, too. The moment really exists among three parties: the subject, the photographer, and the audience. And in this moment, all three are on the moon – the vantage point is so clearly from this other place that it places the viewer there, too, for the first time.

Rebecca Boyle, a free lance science journalist who has written for scores of magazines, captured it best on her blog:

I have often thought about the weird profundity of this Aldrin scene. Armstrong’s small step was momentous, and I have watched the grainy video footage of his descent more times than I can remember. But to me this photo reflects an even more consequential shift. With this perspective, everything changes. It’s the perspective of there, of the already arrived. Until this photo, every image of the moon, in our minds and in our cameras, had been from the other vantage point—from far away, looking up. On the outside, looking in, if you will.

Now one of us was there, on the inside looking out. The human mind was inhabiting the moon, rather than projecting onto it. A human presence was welcoming another visitor.

I have read so many books about the Moon, the Apollo mission and space technology (I have 47 books in my space collection) that it has been near impossible to try and reduce my suggestions to a manageable list, or even manageable themes. So here is my crack at suggestions to give you a “launch pad”:

“A Man on the Moon” by Andrew Chaikin (1994)

For a long time this has been the authoritative text (a fresh crop of books attempts to bring new insight and they are noted below). The strength of the book lies in Chaikin’s exhaustive research, including interviews with all 24 Apollo astronauts. Chaikin draws on the wealth of material from NASA’s files — including what was then recently declassified transcripts from the on-board voice recorders; two fabulous DVDs would be produced using those transcripts (more below) — which give candid glimpses of the astronauts’ thoughts not intended for outside ears (not even Mission Control’s). As a result, the reader gets an in-depth portrait of the program, which the book sets clearly in its time, with glimpses at the Vietnam War and social unrest at home that were eventually to overshadow its brilliant accomplishments.

“Carrying the Fire” by Michael Collins (originally published in 1974 but there was a special edition issued in 2019 for 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 with a new introduction by Collins)

Michael Collins was the command module pilot for Apollo 11. While he stayed in orbit around the Moon, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin left in the Apollo Lunar Module to make the first crewed landing on its surface.

Hands down, this is my favorite astronaut autobiography against which all others are measured. He wrote every word — writing on weekends over an 18‐month period — which probably didn’t help him cut it down any. It runs 500+ pages. And he rambles. But what a fascinating ramble. Given the vast impersonality of NASA, where exploration is done by teams it is nice that such a book can be written at all —that there is room in modern spaceflight for something like a voluble 19th‐century explorer. Collins is breezy, glib, collegiate and frequently funny — you get a true sense of what it is like to be a a test pilot, an astronaut. What he is best at is single impressions — little snapshots, really – of the moon, of the astronaut next to him inside his glass helmet, of a reentry so blazing that he felt as though he were inside a light bulb.

Collins is left alone in the command module — more alone than any man has ever been before when he orbits to the moon’s backside – where he is utterly cut off from the earth. Charles Lindbergh, who wrote the introduction to the book, and who had felt a similar loneliness when he flew the Atlantic, said in a letter to Collins when he returned, “You have experienced an aloneness unknown to man before. I believe you will find that it lets you think and sense with a greater clarity.”

Maybe so. What is clear is no other person who has flown in space has captured the experience so vividly.

“One Giant Leap” by Charles Fishman (2019)

For a one-stop overview of how Apollo unfolded, Fishman’s book wins. It lays out the basics of how NASA designed and built the unprecedented hardware required to go to the Moon, from the mighty Saturn V rocket to the improbably spindly lunar lander. Fishman sets his narrative in the social context of the 1960s, highlighting US fears about Soviet military dominance and the concurrent rise of the civil-rights movement. It shows how Apollo sprang up at a time of international and domestic tumult.

And for the tech junkies amongst you, there are delightfully nerdy chapters, such as one on the development of Apollo’s computer hardware and software. Fishman describes the work of engineer Charles Stark ‘Doc’ Draper’s legendary team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge. This crucial group developed the navigation and guidance systems that enabled the Apollo 11 crew to reach their target, undock the lunar lander and pilot it to a precise site on the basalt plain known as the Sea of Tranquillity (Mare Tranquillitatis). Fishman also lauds the work of Bill Tindall. The NASA manager and engineer knew how to translate MIT’s breakthroughs into a successful mission — deleting extraneous computer code and ensuring that only the most reliable and well-tested commands remained.

“The Moon” by Oliver Morton (2019)

The best in the new crop of books that came out to coincide with the 50th anniversary. The Moo, is a his paean to our “satellite”, providing a complete picture of the Moon in all of its scientific, historical and cultural contexts. This is a book to bend your mind with the mysteries of the swirl-like markings on the lunar surface or the cadence of impacts that have bombarded the inner Solar System. It links the geological history of Earth with the chances of asteroid impacts ferrying life between planets. And it tosses in an apocalyptic scene of the Moon’s birth, from a cosmic collision involving Earth. Morton, a former editor at Nature has written what is surely the most eloquent exploration of our modern understanding of the Moon.

“Eight Years to the Moon” by Nancy Atkinson (2019) and “The Apollo Chronicles” by Brandon Brown (2019)

Inevitably, several books celebrate the engineers behind the Apollo feat. Atkinson’s book features Earle Kyle, one of the few African American aerospace engineers of the time, and Dottie Lee, who not only calculated spacecraft trajectories but also designed and tested the vehicles. I am coupling that with the more personal view in The Apollo Chronicles by Brandon Brown, a physicist whose father worked on the project. Brown takes us leap by leap through the 1960s, tracing the parallel engineering work at Cape Canaveral (the launch site in Florida), the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas (now the Johnson Space Center), and the rocketry group in Huntsville, Alabama, led by German-born Wernher von Braun.

Brown peppers his account with on-the-ground details of how engineers dealt with unexpected problems. Some were simple. In Houston, technicians working to perfect Apollo’s control thrusters panicked on finding a mysterious residue coating vehicles in the car park. Could explosives leak that far from the laboratory? A chemist subsequently identified the substance as goldenrod pollen. Other issues were complex. Revisiting the tragic Apollo 1 fire of 1967, in which astronauts Gus Grissom, Edward White and Roger Chaffee died during a capsule test at the Cape, the horror of engineers familiar with the electrical systems that killed them is palpable.

Yes. In 1961, thousands of minds set fervently to work. Incredulous, they gazed at legions of imposing problems: unsteady, exploding rockets; a largely mysterious lunar surface; and trajectory calculations full of best guesses. With less than nine years to complete a lunar landing, the engineers didn’t have a script. All of this is told with infinite detail by Brown.

Both books chronicle NASA’s scramble of 1962 which was especially inspiring. Waves of employees moved from Langley, Virginia, to Houston. Leaving scenic Virginia, some engineers found their new setting otherworldly enough, with scrublands flat as graph paper. It nearly moved many to tears. The new NASA center, rising from a muddy cattle pasture, wouldn’t be ready until 1964. In the meantime, the agency rented a smattering of buildings and suites around the greater Houston area. In some cases, apartment bedrooms and kitchens became makeshift offices. And without their own armoire-sized computers chugging away, the engineers had to borrow processing time wherever they could find it. In 1962, NASA leaned on an IBM 7090 computer at the University of Houston. Advanced for its time, with transistors instead of tubes, it still required instructions fed to it one punch card at a time, and it returned results the next morning.

One of the most brilliant chapters in Brown’s book is about computing the exact time an orbiting astronaut should start his capsule’s fiery reentry through the atmosphere. A perfect splashdown needed to strike the Earth in daylight, near (but not too near) waiting recovery ships, and without cratering into some landmass or another. One of the engineers recalls carrying his ordered stack of punch cards—his computer program—through driving summer rainstorms, with runoff so strong it lifted manhole covers from the streets.

Even if he kept his cards dry, he often met with frustration when he returned the next day. There was a high failure rate. You’d punch one number wrong into a card, and you got a bunch of wasted paper. Just a bunch of octal numbers that didn’t mean anything. If he threaded the needle—punching his cards correctly and keeping them in order — he still suffered at the whim of the computer facility’s operators.

And you had to make sure you got in the queue … so wrapping your cards in a five-dollar bill helped.

“Apollo’s Legacy” by Roger Launius (2019) and “Moon Rush” by Leonard David (2019)

The Apollo project involved some 400,000 people working for a decade to send a dozen humans to the surface of the Moon. For a holistic analysis, there’s no better source than Roger Launius, former chief historian for NASA. In Apollo’s Legacy, Launius explores the many ways in which the public has interpreted the landings — from denial to embracing the whole-Earth view from space. He reminds us that the Apollo project, although often lauded as a visionary achievement, was not well accepted by many in the United States — including scientists — at the time. A 1967 poll found that residents in six US cities saw tackling pollution and poverty, for instance, as more important.

On the eve of the Apollo 11 launch, civil-rights leader Ralph Abernathy took several hundred people to Cape Canaveral to demonstrate against the massive spending on the space programme in the face of poverty and social injustice. “We do not oppose the Moonshot,” said Hosea Williams, a leader of the group. “Our purpose is to protest America’s inability to choose human priorities.” Politics, science and engineering working in concert, Launius notes, might have been able to send a man to the Moon, but back on Earth, solutions to egregious social issues such as racism and inequity were and are slow in coming. Many people continue to hold up Apollo as an example of how the Moonshot approach might solve some of the most pressing problems facing society, such as climate change. History shows this analogy is far from perfect.

Today, following in the steps of former presidents George H. W. and George W. Bush, Donald Trump — certainly no Kennedy — has tasked NASA with returning astronauts to the lunar surface by 2024. But the landscape now is wildly different, as journalist Leonard David describes in Moon Rush. Commercial companies such as SpaceX and Blue Origin are entering the realm of space flight, and China is a strong contender for sending the next human to the Moon.

“The NASA Archives: 60 Years in Space” edited by Piers Bizony, Roger Launius, Andrew Chaikin (2019)

This is an expensive tome ($150.00). The texts are by science and technology journalist Piers Bizony, former NASA chief historian Roger Launius (noted above), and Apollo historian Andrew Chaikin (also noted above).

This book was also issued on the occasion of the 50-year anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing but NASA wanted to illuminate NASA spaceflight history from its beginning with the historic Bell X-1 flight of Chuck Yeager to break the sonic barrier in 1947, till the most recent robotic travels to Mars. There are quite a few photos from the NASA Archives that have never been shown before.

Many of us know the photos, videos and quotes from the Apollo missions by heart. But if you are from a generation not born yet at the time of the Moon landings and you want a “WOW” book, this is it. An opulent book produced expensively, the photos are visually more than intriguing and while browsing through the book you feel an immediate flash-back to the beginning of spaceflight. It’s almost like feeling the Apollo moment again.

DVD: “Apollo 11” (2019)

Apollo 11 is a cinematic space event film quite literally fifty years in the making. It is an American documentary film edited, produced and directed by Todd Douglas Miller. It focuses on the 1969 Apollo 11 mission. The film consists solely of archival footage, including 70 mm film previously unreleased to the public, and does not feature narration, interviews or modern recreations. The Saturn V rocket, Apollo crew consisting of Buzz Aldrin, Neil Armstrong, and Michael Collins, and Apollo program Earth-based support staff are prominently featured in the film.

When you watch the quality of the footage you’d think it was filmed today. And they do a great job mixing this footage alongside conventional footage from 35 and 16 mm film, still photography, and closed-circuit television footage.

The backstory is incredible. In May 2017 the cooperation between Miller’s production team, the NASA, and the National Archives and Records Administration resulted in the discovery of unreleased 70 mm footage from the launch and recovery of Apollo 11. The large-format footage was “listed” but nobody on any of the teams had scene it.

They ended up cataloging over 11,000 hours of video and audio recordings. Among the audio recordings were 30-track tapes of voice recordings at every Mission Control station. No one had heard these tapes for almost 40 years.

As a film producer I was fascinated by the process. Miller’s team had to use the facilities of Final Frame (a well known post-production firm in New York City; I have used them) to make high-resolution digital scans of all available footage. Specialized climate-controlled vans were used to safely transport the archival material to and from the National Archives in Washington, DC.

Ben Feist, a Canadian software engineer, was tasked with writing a software to improve the fidelity of the newly available audio. British archivist and film editor Stephen Slater, who had synchronized audio recordings with 16 mm Mission Control footage in earlier projects, performed the task of synchronizing the audio and film.

It is a brilliant, brilliant movie.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *