The view from the apartment I usually rent when I attend IJF, this year given to my staffers.

No, she did not attend IJF. But no doubt she would also agree that Perugia

is not a bad place to existentially question the entire journalism industry

26 April 2019 (Brussels, Belgium) — The internet used to be a vast and wondrous place. It was fun. It began simply as a giant data set, a contextless compendium of information consulted via websearch, a query to fill whatever momentary gnaw had interrupted your day. And it can still have that function. But …

Introduction

Once the internet evolved past the novelty of communicating over distance, it found value in experience. Forums proliferated, naturally subdividing so that people congregated around shared interests or life events. Those of us who were into the Net early on will well remember that waaaaaaay back in 2003 there was the launch of a now legendary community-run via MetaFilter which was called “Ask MetaFilter” where users could pose questions to the “hive mind.” AskMeta still exists but it has become what Peter Rubin (culture editor for Wired magazine) calls a “lurker’s dream”. You scroll through not to answer, or even look for something specific, but just to absorb the amazing content: road-trip conversations, playlists, science and literature tutorials – complete lives and stories revealed not in parcels but told in full.

But then, alas, scale and greed and countless other culprits spun the internet geologic clock backward. A realm that once comprised countless nations has become a supercontinent, a monolith of homogenized use and mood. We have “hell sites” (Facebook and Reddit and Twitter and 4chan to name but four), not web sites, that manage to be more existentially unsatisfying everyday, manipulating our traditional knowledge ecosystem. And so our days are filled with discussions of “the struggle to detoxify the internet” and “the oxygen of amplification” which have reconfigured the information and media landscape … and not in a good way.

As recently as 15 years ago, before the internet completed its digital disaggregation of the newspaper business, I was a two-paper-a-day-via-the-plastic-delivery-bag guy: the Financial Times and Le Monde. But over time I would turn first to my desktop computer and then to my laptop and finally to my phone for news; digital subscriptions became my primary “information delivery system”. Beckoned incessantly to click on one link or another. Or still another. Those mysterious algorithms known only to the gremlins of Silicon Valley pushing me toward stories that those gremlins reckon must be of related interest. But I have returned to my old morning ritual of actually reading a print paper. More on that below.

So as I watch the break-down and disintegration of my “imagined communities” (to use the late Ben Anderson’s term) … nation states, professions, civility, legal systems, etc. … I find the need to ask questions. Well, ask more questions than I do. It’s Socratic: examine one’s life. There are things that burn away at me, not only as a private individual, but also as a citizen of our century, our pixelated age. What can I do with the absurdity of life that swarms me daily? Well, the most I can do is to write — intelligently, creatively, evocatively — about what it is like living in the world at this time. And yes, parsing the what-it-is-like can itself drive me to despair. Still, parse I must.

What people don’t get

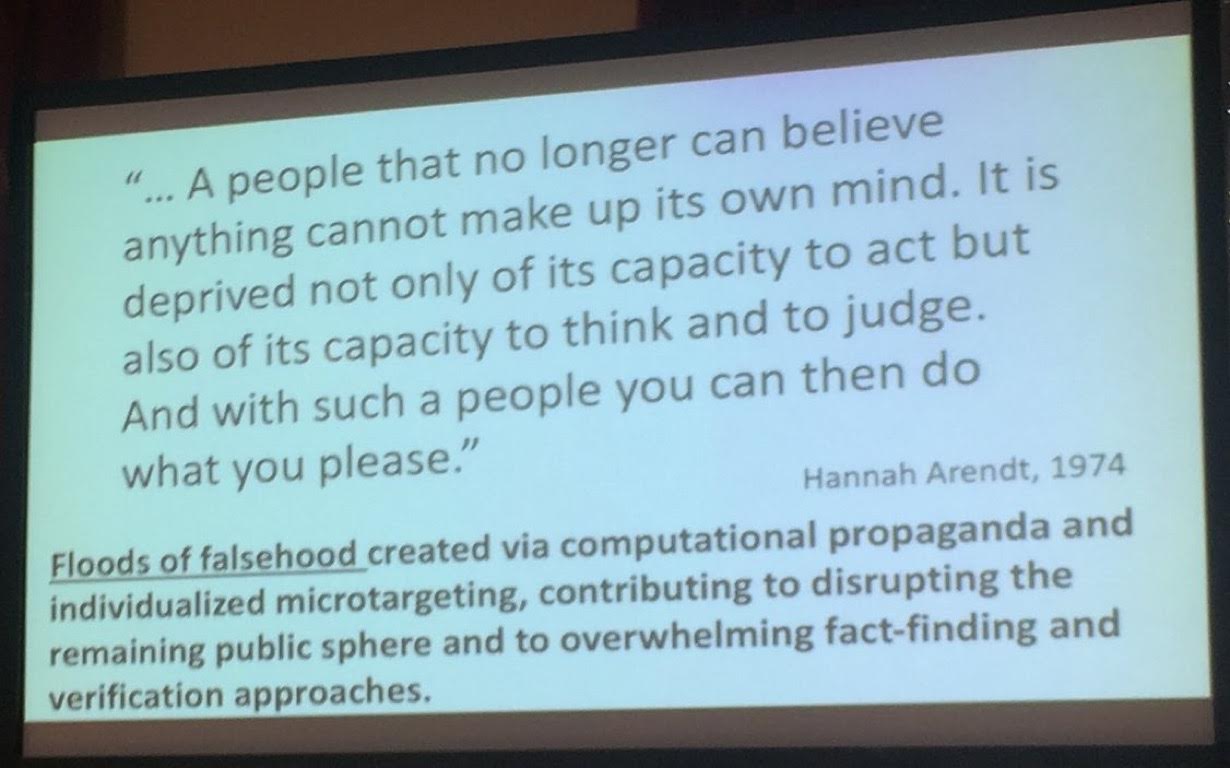

People that use the Cambridge Analytica story as a way to undermine Brexit or the Trump vote is missing the key, key point: people’s trust in elections and the long-term effect of profiling and micro-targeting on politics is that the whole of politics and much of life has been reduced to a data science. Societal worry about algorithms and nudges online should focus ahead ten years as these data systems improve. These powerful machines (and they are machines) have resulted in our collective self slowly losing the practice and ability to think for ourselves, as we cease to act as moral agents. I do not fear an anarcho-capitalist collapse. I see our happy drift into something more dreadful: techno-authoritarianism. Earlier this year I was at a privacy conference and the presenter (a U.S. lawyer) railed against China which “operates with less scrutiny and regard for corporate social responsibility than their Western counterparts”.

My God, in what world does he live!! The U.S. government is happy to allow companies to profit off the exact same activities and charge the taxpayers to use the information against themselves. And the kicker is that everyone volunteers for this surveillance by buying the very devices used to track them .. playing free games and every other imaginable app … and thereby know their activity, their geo-position, etc. The U.S. government (any Western government) could care less about protecting our privacy (please, don’t get me going on the GDPR; I will rip that to shreds in my next post).

Which is why every year my “go to” event is the International Journalism Festival in Perugia, Italy. It is, to put it simply, my intellectual sauce every year.

Well, except this year. Due to a rather severe spinal injury I suffered in February from which I still recover, my travel is restricted. So my staffers covered the Perugia event, live-streaming presentations with their GoPros (in addition to those live steamed by the event organisers itself), plus live streaming a large number of the interviews they conducted so I could also ask questions. Bless their hearts.

The International Journalism Festival in Perugia, Italy

We live in a time where new forms of power are emerging, where social and digital media are being leveraged to reconfigure the information landscape. This new domain requires journalists to take what they know about abuses of power and media manipulation in traditional information ecosystems and apply that knowledge to networked actors, such as white nationalist networks online. These actors create new journalistic stumbling blocks that transcend attempts to manipulate reporters solely to spin a beneficial narrative – which reporters are trained to decode – and instead represent a larger effort focused on spreading hateful ideology and other false and misleading narratives, with news coverage itself harnessed to fuel hate, confusion, and discord.

And so the choices reporters and editors make about what to cover and how to cover it play a key part in regulating the amount of oxygen supplied to the falsehoods, antagonisms, and manipulations that threaten to overrun the contemporary media ecosystem — and, simultaneously, destroy the democratic discourse more broadly. Yes, they make lots (and lots) of mistakes but many of them do really top-notch work.

And there is no better venue than the International Journalism Festival (from hereon “IJF”) to understand how this all works. Why? Especially? Because the IJF is that rarest of things: a swooning, soul-enriching community – from huge media legacy players, to small media upstarts, with the biggest names in journalism and media analysts plus the smallest but most articulate media players – all struggling with different versions of similar challenges and stories. There is not one journalism or media event anywhere in the world on either the newsroom side or the business side that brings the eclectic global examples of success and failure and utter transparency.

Attendance to IJF is free to the public, and not one presenter or panel member is paid by the event organizers (this year: 340 sessions and 810 speakers over the 5-day program). All presenters/panelists attend under their own steam – their own travel, their own accommodations, their own meals. There are, of course, operational expenses but they are paid by the European Journalism Centre and the Open Knowledge Foundation. Plus there are 280 student volunteers, almost all of them young and almost all aspiring journalists who cross the planet (coming from Brazil to Uzbekistan) at their expense (although the festival does provide them free accommodation and a hearty lunch, plus a few of us cover their breakfast).

So in a world of pay-to-play conferences, it is totally refreshing. And the diversity? Women make up one-half of the panels.

Yep. Just a week of scores of sessions in beautiful venues (that’s the Opera House in the photo above) to spend time with some wonderful people for no-holds-barred conversations, and transparency galore.

To help you navigate the remainder of this post, I have divided it into the following sections which are based on what I saw as the main “talking points”. In an event of this size it is impossible to attend everything because of conflicting schedules. But the organisers make sure that some of the major, “hot” topic areas are repeated throughout the week, by different panels. The following summaries include one-off/single events, plus “mash-ups” of panels that were covering the same topic. I normally have eight people cover IJF and that includes a few who are local to Perugia so we can cover as much as possible.

So the following sections are titled as follows:

* The big take-aways

* A cognitive scientist explains why humans are so susceptible to fake news and misinformation

* Journalists are under increasing physical threat

* A different approach to journalism: evidence and data-driven

* Editing is the new coding. As the market becomes saturated with content-heavy platforms, the most promising careers are in storytelling.

* How the media helped legitimize extremism

* Power in the shadows. In politics, Facebook is creating the next version of the public square, only it’s a private square.

* Russia’s social media efforts are often incorrectly thought of as purely election interference. They’re actually a year-in, year-out slog [UPDATED TO ADDRESS THE MUELLER REPORT BOTS AND TROLLS]

* Did someone say hypocrisy? Twitter as an example of the false notion of big tech self-regulation

* There’s no substitute for print

* The big take-aways

Let’s start with what I think were the big take-aways from IJF this year, and then my thoughts on what is happening:

1) There is a war on journalism being waged by some very powerful people, often especially targeting women. The murder count has spiked as I detail below. Governments have launched coordinated campaigns of paid trolls, fallacious reasoning, and leaps in logic … in effect “poisoning the well” to shift public opinion on key issues. The Committee to Protect Journalists and other organizations have documented these state-affiliated campaigns which often directly target journalists in an attempt to intimidate and silence reporting.

2) The exponential growth of big tech platforms in information delivery has led to the digital disaggregation of the newspaper business, and other old line media. And so more and more journalists are being asked to step into roles that previously were the sole domain of the business side. The Guardian‘s membership scheme is run by a journalist. More and more newsrooms are investing in audience development teams. And many journalists are moving into product or tech-related roles. Yet, journalists by and large rarely have the experience or training they need to fill these roles.

3) No one will “save us” but there’s hope in collaboration, sharing, solidarity. The relationship between platforms and publishers is a defining feature of journalism today. It is changing the state of the relationships across editorial, data-sharing, product development, and business relations. With its share of opportunities and risks.

4) Both “data” and “journalism” are troublesome terms. And for most journalists “data” is still just a collection of numbers, most likely gathered on a spreadsheet. And, yes, 20 years ago, that was pretty much the only sort of data that journalists dealt with. But we live in a digital world now, a world in which almost anything can be - and almost everything is - described with numbers. So journalists are learning that those 300,000 confidential documents, those photos, those videos, etc. are described with just two numbers: zeroes, and ones. Murders, disease, political votes, corruption and lies: zeroes and ones. And they are learning about all the new possibilities that open up when you combine the traditional “nose for news” and ability to tell a compelling story, with the sheer scale and range of digital information now available. And those possibilities can come at any stage of the journalist’s process where they are learning to use an array of digital tools to program/automate the process of gathering and combining information from local government, police, and other civic sources. Or using software to find connections between hundreds of thousands of documents. To help a journalist tell a complex story through engaging infographics. [NOTE: this requires a more detailed exposition … a draft is in process … to explain the actual digital tools in the journalist’s toolbox which include many that will be familiar to my e-discovery industry readers.]

My view

When I review all of the material gleaned from my conversations/my team’s conversations at IJF plus those at the International Cyber Security Forum, the Mobile World Congress and the Munich Security Conference, as well as chats with my journalism contacts, and couple that with the readings from my formidable library …

A few selections from my 172 volume “Information Age” book collection

… I come away with these overriding issues:

* There is an incompatibility problem, one between an old system (mass party-nation-state level representative democracy) and a new one (borderless, networked internet technology).

* We have been blinded by the very big benefits to individual liberty the internet has created but we have ignored the boring things that make democracy work: strong middle class, shared sense of reality, local journalism, elections we trust, effective policing, etc. We have let those completely erode.

* We have helped accelerate identity politics and, once started, everyone is now incentivised to engage in it. Technology has made it so easy to sift through leaked emails, strip out individual sentences and phrases out of context, and then spin them to look sinister. And then mainstream media dutifully covers the “controversy.”

* This is not about “stupid people” voting the wrong way – a patronising liberal orthodoxy – but the long term challenges to modern democracy in a world of AI, big data, ubiquitous connectivity.

* As I noted above, we have reduced everything to a data science. Our politics, our culture is being steadily absorbed into the discussion of business. There are “metrics” for phenomena that cannot be metrically measured.

* A cognitive scientist explains why humans are so susceptible to fake news and misinformation

The Nieman Journalism Lab presented Julian Matthews (a research officer at the Cognitive Neurology Lab of Monash University) who studies the relationship between metacognition, consciousness, and related cognitive processes.

Fake news often relies on misattribution – instances in which we can retrieve things from memory but can’t remember their source. Misattribution is one of the reasons advertising is so effective. We see a product and feel a pleasant sense of familiarity because we’ve encountered it before, but fail to remember that the source of the memory was an ad. One study examined headlines from fake news published during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. The researchers found even a single presentation of a headline (such as “Donald Trump Sent His Own Plane to Transport 200 Stranded Marines,” based on claims shown to be false) was enough to increase belief in its content. This effect persisted for at least a week, and it was still found when headlines were accompanied by a fact-check warning or even when participants suspected it might be false.

Repeated exposure can increase the sense that misinformation is true. Repetition creates the perception of group consensus that can result in collective misremembering, a phenomenon called the “Mandela Effect”: a common misconception and misquoted line that perpetuates itself deep within our culture.

Donald Trump uses it to its max: just keeping repeating repeating repeating the same false thing and it will eventually solidify and become “true”. As I have noted before, the mass rallies that Trump has made normal acknowledge no distinction between national politics and reality TV. He coaxes, he cajoles and he comforts his audience.

Oh, and it can also be in harmless stuff, too. We collectively misremember something fun, such as in the Disney cartoon “Snow White”. No, the Queen never says “Mirror, mirror on the wall …” She said “Magic Mirror on the wall …” But it has serious consequences when a false sense of group consensus contributes to rising outbreaks of measles.

At the core of all of this is bias. Bias is how our feelings and worldview affect the encoding and retrieval of memory. We might like to think of our memory as an archivist that carefully preserves events, but sometimes it’s more like a storyteller. Memories are shaped by our beliefs and can function to maintain a consistent narrative rather than an accurate record.

Our brains are wired to assume things we believe originated from a credible source. But are we more inclined to remember information that reinforces our beliefs? This is probably not the case. People who hold strong beliefs remember things that are relevant to their beliefs, but they remember opposing information too. This happens because people are motivated to defend their beliefs against opposing views.

One of the key points made was that “belief echoes” are a related phenomenon that highlight the difficulty of correcting misinformation. Fake news is often designed to be attention-grabbing. It can continue to shape people’s attitudes after it has been discredited because it produces a vivid emotional reaction and builds on our existing narratives. Corrections have a much smaller emotional impact, especially if they require policy details, so should be designed to satisfy a similar narrative urge to be effective.

So the way our memory works means it might be impossible to resist fake news completely. One approach suggested is to start “thinking like a scientist”: adopting a questioning attitude that is motivated by curiosity and being aware of personal bias, and adopting the following questions. But look at this list of questions and tell me … how many people are really going to do this?

1. What type of content is this? Many people rely on social media and aggregators as their main source of news. By reflecting on whether information is news, opinion, or even humor, this can help consolidate information more completely into memory.

2. Where is it published? Paying attention to where information is published is crucial for encoding the source of information into memory. If something is a big deal, a wide variety of sources will discuss it, so attending to this detail is important.

3. Who benefits? Reflecting on who benefits from you believing the content helps consolidate the source of that information into memory. It can also help us reflect on our own interests and whether our personal biases are at play.

* Journalists are under increasing physical threat

The share of countries classified as good or fairly good when it comes to press freedom has slightly decreased to 24 percent, according to the Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index, which was shown at IJF but only officially published this week.

Norway (No. 1 for the third consecutive year), Finland, Sweden, the Netherlands and Denmark are the Top 5. Guess who’s at the bottom? Only Turkmenistan is worse than North Korea. Rounding out the worst five: Vietnam, China and Eritrea.

It isn’t pretty. Threats, insults and attacks “are now part of the ‘occupational hazards’ for journalists in many countries,” according to the report, pointing to India (140th place out of 180) and Brazil (105th). But you don’t need to look that far from home — murders of journalists in Malta, Slovakia and Bulgaria “have made the world realize that Europe is no longer a sanctuary for journalists,” the report says.

* A different approach to journalism: evidence and data-driven

There was a presentation on The Markup, a highly anticipated nonprofit news site that planned to explore the societal impacts of big tech and algorithms. And it is perhaps a little prophetic that I am writing this today because this week Julia Angwin, its much-respected cofounder and editor-in-chief, was fired. The Markup’s editorial team published a letter of “unequivocal support” for Angwin, who says that she was let go over email Monday night. The move baffled journalists on Tuesday, but Angwin said her ouster was the result of tension over the editorial mission of the site — specifically, whether it should take an “advocacy approach” or an “evidence- and data-driven approach.”

This is all rather important to the industry. I know Angwin (a Pulitzer Prize winner and two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist) because she actually reads my stuff. She had left ProPublica about a year ago to launch the site.

Note: ProPublica is legendary. Their writers have won scores of Pulitzer prizes. Their coverage of “Trump, Inc.”, exploring every highway and byway of Trump’s businesses, is equal to none. Last week their “Trump, Inc.” team gathered with laptops, pizza and Post-its to read the Mueller’s report, their focus on the rich details in the Report on how Trump ran his business dealings in Russia, having escaped the redaction machine.

At ProPublica, Angwin had been an investigative reporter who’d built a team pairing programmers and journalists that specialized in investigating the opaque algorithms that influence our lives. ProPublica data scientist Jeff Larson went with her, and Sue Gardner, formerly of the Wikimedia Foundation and the CBC, was their third cofounder and executive director.

From the Tweets I have read and colleagues in the business, it seems she was forced out of the organization because she wanted to pursue a rigorous, evidence-based tech accountability journalism buy the others wanted to change the mission of the newsroom to one based on advocacy against the tech companies … so a “cause” rather than a “publication”. FYI: it was Craiglist founder Craig Newmark who provided the $23 million that The Markup needed to launch.

These tensions are increasingly common in reporting on technology. The largest tech companies, accustomed to generally positive press until the 2016 Brexit and Trump elections, are now often seen as powerful titans destabilizing democracies, fueling misinformation and violence, encoding discrimination, and almost offhandedly crushing industries. Some journalists have moved to combine investigative reporting with a bit of the crusader’s zeal — like The Observer’s Carole Cadwalladr, who has done an excellent reporting job on issues like the Cambridge Analytica scandal and the manipulation of the Brexit vote.

To me, The Markup was going to be a new kind of journalistic organization, staffed with people who know how to investigate the uses of new technologies and make their effects understandable to non-experts. The work was to be scientific and data-driven in nature. They had developed a process to create a hypotheses and assemble the data – through crowdsourcing, through FOIAs, and by scraping public sources – to surface stories. As of this writing, the fate of The Markup without her is unclear.

* Editing is the new coding. As the market becomes saturated with content-heavy platforms, the most promising careers are in storytelling.

When your smartphone can access any song, movie or book ever created, and you can use it to do anything from ordering food to finding dates to getting rides, companies are realizing they need a new weapon in the war for attention: an editor in chief.

The big picture: Because it’s never been harder for companies to reach distracted consumers, more and more firms are hiring editors and content creators to build everything from podcasts to news websites to print magazines to grab your interest. In the smartphone-dominated world — where any media company can access almost anyone at anytime — the fight is shifting to dominating a person’s attention. So there’s a growing need for the type of people who can steer teams to tell stories and deliver information in a way that gets potential customers to take heed.

Just skimming a few announcements and what is out there driving the news:

-Airbnb this year started a print magazine — it’s free for hosts or $18/year for everyone else.

-Bumble, a dating app, launched a lifestyle magazine.

-Netflix published a free magazine to promote its programs and stars ahead of this past year’s Emmy Awards show.

-BlackRock, the giant money manager, recently hired a global head of content.

-Robinhood, a millennial-based financial services company, last month bought MarketSnacks, a financial newsletter and podcast company.

-Stripe, a payments company, published a book last year.

-Goldman Sachs has a talk show.

-Blue Apron, Slack, Away, Shopify and Casper have created their own podcasts.

-Verizon is hiring an “Editor in Chief-Social” to oversee an editorial team tasked with “high frequency coverage” of Verizon activities.

By the numbers: The proportion of people on LinkedIn who report they work in content/editor roles at non-media companies has grown by 32% in the past decade, according to LinkedIn data. The biggest increases were at “consumer,” “high tech” and “corporate” firms, like marketers and consultancies.

Yes, but … much of this content creation is not typical news or journalism; many of these editor jobs are more accurately described as “head of content” roles. And as Felix Salmon of Axios noted:

Basically the adjacency model is a gruesomely inefficient way for companies to communicate. It’s, like, here’s something you do know that you want to read, let’s put it next to something you don’t particularly want to read, and maybe you might read that anyway.

Much better to create something that people do want to read directly, and give them that. You know how every company is a technology company? Well maybe on some level every company is a media company, too. There’s no point felling trees in forests if nobody hears them.

* How the media helped legitimize extremism

I can say this: there aren’t too many industry conferences out there where the some of the speakers/panels are free to skewer their own industry. There were several sessions where journalists provided a penetrating indictment of journalism’s internal inconsistencies. I covered some of this above in my introduction. But herein a few more points:

For the past few years, reporting on far-right extremism and misinformation has been a messy free-for-all. Sure, there have been some attempts to delineate best practices, and certain approaches to storytelling, such as those that seem to normalize neo-Naziism, have come under harsh criticism. But few rules have guided the new genre of reporting.

There is a fundamental paradox of reporting on the so-called “alt-right”: doing so without amplifying that ideology is extremely difficult, if not downright impossible. Reporting may be complicit in spreading far-right messaging and helping the movement grow.

Several reports on the issue have come out of the Data & Society research institute’s Media Manipulation Initiative, the main one written by Whitney Phillips (who I profiled last year, author of This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship Between Online Trolling and Internet Culture).

Bottom line, an uncomfortable truth: journalists inadvertently helped catalyze the rapid rise of the alt-right, turning it into a story before it was necessarily newsworthy. Now, there’s no turning back. We have to deal with the reality of a highly visible, activated, far-right element in our culture.

But there are ways for journalists to do better. It’s not that the reporting was done in bad faith or ill-intentioned; many people thought that holding up a light to the hatred of white supremacist groups would force them to go away. But that didn’t happen. If it were true that light disinfected, the alt-right would not have taken off in the way it did. Instead, the very act of exposure, combined with stories that unwittingly framed extremism as a victimless novelty, legitimized and empowered an otherwise fringe perspective.

Many pundits and analysts have written on this: even as white nationalism was thrust into the national spotlight, some journalists had trouble taking it seriously. Phillips discusses the impact of “internet culture,” or “meme culture,” on digital natives’ ability to spot extremist content. Much content is, in fact, satirical. And that assumption of irony is typical of many people raised around internet culture. Said Ryan Milner, an assistant professor of communication at the College of Charleston (he co-authored along with Phillips, the chap I noted above, a brilliant book The Ambivalent Internet: Mischief, Oddity, and Antagonism Online which I highly recommend):

Blanket irony is watching something from a distance and being able to detach yourself from its reality and its depth and its nuance. It is hard to break — and by the time many journalists realized the non-ironic, non-satirical truth about what was happening, the damage had already been done.

Phillips, in his study The Oxygen of Amplification from which I borrowed the title of this post, tried some perspective:

Let’s be careful not to lay blame place at the feet of individual reporters, instead seeking to address structural flaws in the way many outlets think about extremism and extremists. We need some criteria for determining newsworthiness, such as: Has a given meme been shared beyond just the members of the group that created it? If not, all reporting will do is provide oxygen, increasing the likelihood that it will reach the tipping point.

And, of course, in the case of the so-called alt right as a whole, that’s exactly what’s happened: in amplifying alt-right ideology even in cases where it wasn’t necessarily newsworthy, journalists made it newsworthy. But by keeping that tipping point calculus in mind going forward, journalists can help avoid the continuation of a vicious cycle.

I think a common theme is a simple call for self-awareness. An enormous first step in the issue is acknowledging that the system is being gamed, and individual reporters reflecting on the fact that they’re part of that system being gamed. It is much like certain elements of the financial press. Or should I say the “financial press”. We know that the big financial players have learned that with right amount of bots you can easily mislead and the market can be easily disrupted. There are no guard rails. Regulation fails. So when a writer with/from “a financial network” posts something with a good, trick headline to get attention, you need to track it through. Because they’ll then add a number of fake accounts, bots and then bang … you have manipulation.

With the “alt-right” it is much more difficult, and it takes a lot of work. It’s easier said than done, especially as long as ad-supported journalism is the status quo. A real reckoning with journalism’s complicity in amplifying far-right messaging would require a fundamental shift in editorial strategy in many newsrooms. Many of Phillips’s recommendations reflect the basic principles of good journalism, but those can also be at odds with the realities of an industry that emphasizes speed and traffic. It’s all of these other pressures, like time and competition and lack of expertise within an area, that can introduce problems into the content produced.

This is why I have a 10-person media team. You need to make an effort, take the time to talk with people who have direct, embodied experience with the interpersonal, professional, and/or physical implications of a given issue, something that of course most journalists would aim to do, but that is not always feasible, given time pressures. And as Roisin Kiberd, a freelance writer for numerous online publications, said:

I don’t really know any journalists who get up in the morning, look in the mirror, and say, ‘Today I’m going to be unethical’. It’s all of these other pressures, like time and competition and lack of expertise within an area, that can introduce problems into the content that we produce.

And we all have the same queasiness, conscious of the fact that our writing is feeding directly into far-right extremists’ agendas — but who are also rewarded for their coverage. We’re all damned, because we all profit off it. Even if we don’t make money off it, we tweet and we get followers from it.

I know from colleagues the pressure to build a personal brand, meet quotas, and compete with other publications. It is not easy for every writer to take an eminently thoughtful and nuanced approach to the stories they’re assigned, or to reject an assignment outright due to concerns about amplification.

Because capitalism does not align with most of those recommendations. If an organization is dependent on advertising revenue, and if these best practices are going to — and they would — result in less advertising revenue, then publishers would have to be willing to take a considerable financial hit to make the appropriate changes to minimize the spread of mis- and disinformation. The bottom line is that people have to be willing to sacrifice the bottom line. And if they don’t? Face it: we lose truth, and democracy becomes more untenable.

* Power in the shadows. In politics, Facebook is creating the next version of the public square, only it’s a private square.

Facebook, struggling to free itself from one political scandal after the next, has moved forcefully into the private social network business. It is probably not going to free them of public and political responsibilities. If anything, it may do the opposite.

But for politics, Facebook is creating the next version of the public square, only it’s private. The private social network looks set to be the next wave of the internet and – like the waves that have come before – it’s likely to be misunderstood and underestimated. Much like the bulletin boards, then “user-generated content”, social media platforms and messaging apps, private social networks are hailed for offering community and creativity, cohesion and connection. And yet, private social networks are harder to police for truth and responsibility. They are even more prone to sowing division, fostering polarisation and enabling communities of hate. They represent the new battleground between politics and the internet.

* Russia’s social media efforts are often incorrectly thought of as purely election interference. They’re actually a year-in, year-out slog [UPATED TO ADDRESS MUELLER REPORT BOTS AND TROLLS]

Russia’s social media efforts are often incorrectly thought of as purely election interference. But the fact is they aim to capitalize on any major news story to fracture the U.S. public.

There was a presentation by MIT Media Lab on a study by a research team at George Washington University who had examined 1,793,690 tweets, collected from July 14, 2014, through Sept. 26, 2017, to explore how polarizing anti-vaccine messages were broadcast and amplified by bots and trolls. They found that in some cases, Russian trolls linked to the Internet Research Agency, a group known to have been involved in 2016 election interference, used a Twitter hashtag designed to exploit vaccination as a political wedge issue. They also found that Russian trolls and sophisticated Twitter bots posted content about vaccination “at a significantly higher rate than did nonbots.” The evidence showed this was just one attempt out of scores made to promote discord outside of election interference.

While an interesting study, I want to preempt those details with a report on the Russian bots and trolls used to immediately capitalize on the Mueller report, according to research from SafeGuard Cyber issued this week.

Details: SafeGuard maintains a database of 600,000 “bad actors” — a mix of automated accounts (bots) and manually controlled accounts (trolls). SafeGuard attributes many, not all, to Russia. They are but one company we use for our cybersecurity analysis and research for clients.

Russian bots and trolls increased their rate of posting by 286% on April 16, the day Mueller’s report was released, and the number of unique accounts posting increased by 48%. It’s pretty clear what they were talking about. The top 5 hashtags were #mueller, #muellerreport, #trump, #barr, and #russia, with the rate of #muller increasing more than 50-fold. Noted in the SafeGuard press release:

What we are saying: the goal here is to get out the content with so much force that getting one or two retweets a time will reach a huge audience. We didn’t just see an increase in activity, we saw an increase in the potency of the accounts used. But we expect these numbers will pale in significance once the 2020 Presidential election gets underway and the full force of the Russian misinformation/disinformation machine kicks into gear.

In the days leading up to the Mueller report, the average account the company classifies as Russian had 13,500 followers. After the report was released, that number spiked to 18,600.

NOTE: I will have another “long read” post within the next few weeks on the incredible sophistication of the Russian misinformation/disinformation machine, with material gleaned from conversations at IJF plus the International Cyber Security Forum, the Mobile World Congress and the Munich Security Conference, as well as chats with my cyber/intelligence community contacts. For example, how videos funded by the Russian government get on Youtube and how the Russians “game” the YouTube algorithms so the videos get recommended by more than 236 different channels: Fox News, Business Insider, FRANCE 24 English, CBS This Morning, BBC Newsnight, Israeli News Live, etc., etc.

The elections in 2020 will be so much weirder than anyone is expecting, and YouTube will be at the heart of that. We’ll drown in user-generated political content like the new political vaporwave genre.

But who needs the Russians? As Tech for Campaigns (these guys bring all manner of tech to election campaigns) noted in its presentation at IJF, both the Democrats and Republicans are pouring money into digital advertising to hit the “hot-button” issues like gun control, abortion, immigration and climate change:

It will be 2016 again, but on steroids. The Democrats learned the hard way what the Republicans had already mastered: content needs to be emotion-driven. Polarizing topics need to be pushed via ads on social platforms, where algorithms elevate content that tends to be more emotion-driven.

Look, for the foreseeable future social media will lead in the attention war. You need content that makes people stop scrolling — that’s what these emotionally-charged issues do.

* Did someone say hypocrisy? Twitter as an example of the false notion of big tech self-regulation

Most of us know the story about the actor Liam Neeson who had to go on a national talk show tour to try and convince the world that he is not a racist. While promoting a revenge movie, the Hollywood actor had confessed that decades earlier, after a female friend told him she’d been raped by a black man she could not identify, he’d roamed the streets hunting for black men to harm. That story caught the eye of the poet Shawn William who Tweeted:

On the day that Trayvon would’ve turned 24, Liam Neeson is going on national talk shows trying to convince the world that he is not a racist.

Carolyn Wysinger, a high school teacher in Richmond, California who is also an activist whose podcasts explore anti-black racism, saw the William Tweet and ReTweeted it with the comment:

White men are so fragile and the mere presence of a black person challenges every single thing in them.

It took just 15 minutes for Twitter to delete her post for violating its community standards for hate speech. And she was warned if she posted it again, she’d be banned for 72 hours.

Amarnath Amarasingam, an extremism researcher at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, was not surprised by any of this. He said black people can’t talk about racism on Twitter or Facebook without risking having their posts removed and being locked out of their accounts in a punishment commonly referred to as “Twitter jail.” The Neeson posts are just another example of Twitter (and Facebook) arbitrarily deciding that talking about racism is racist. He said:

Black activists say hate speech policies and content moderation systems formulated by a company built by and dominated by white men fail the very people Facebook claims it’s trying to protect. Not only are the voices of marginalized groups disproportionately stifled, Facebook rarely takes action on repeated reports of racial slurs, violent threats and harassment campaigns targeting black users, they say.

This happens more frequently on Facebook. Seven out of 10 black U.S. adults use Facebook and 43 percent use Instagram, according to the Pew Research Center. And black millennials are even more engaged on social media. More than half – 55 percent – of black millennials spend at least one hour a day on social media, 6 percent higher than all millennials, while 29 percent say they spend at least three hours a day, nine percent higher than millennials, Nielsen surveys found.

The biggest issue that no algorithm can solve? Confusing advocacy and commentary on racism and white complicity in anti-blackness with attacks on a protected group of people. How do you identify when oppressed or marginalized users are “speaking to power”?

* There’s no substitute for print

Last year I returned to a ritual I had performed for years … reading a real newspaper. An actual printed copy! With a steaming cup of coffee. Or as Alex Jeurgeson, a writer for The Atlantic Magazine, calls it when he reads print “with the essential cup of java, as a chalice to the Eucharist or a hand-thrown bowl to the tea ceremony”.

A quick scan of the front page to get your bearings and then the plunge inside, to international news or an annoying columnist or a review of an unexpected book.

It is like the world opening up through a parting cloud. But it is a very special world, almost an invented world, and here is the key to its charm: it is pleasingly static. It is a settled matter. My news on paper isn’t subject to updating until tomorrow morning. There is a caravan of migrants approaching the Mexican border and that’s where they will stay … approaching … until the paper tells me differently in the morning.

But there is also a psychic benefit. I sit in my newspaper chair (yes, I have a special chair when I read in “leisure mode”) … unmolested. Nothing is beckoning me to incessantly click on one link or another or still another, boxes of irrelevant video appearing and disappearing, audio screeching out unbidden, ads scurry across the screen obstructing the paragraphs I’m trying to read. Those mysterious algorithms known only to the gremlins of Silicon Valley … as I noted above … pushing me toward stories that the gremlins reckoned MUST be of related interest. (Yes, I did click on the story about Cristiano Ronaldo’s surgery but, damn, did I request a pop-up review of some of the latest developments in orthopedic surgery?)

My newspaper could NEVER be so noisy or presumptuous. It holds still.

The relative benefits of reading on paper versus reading on a screen have been examined by buckets of social scientists and neuroscientists. I have read most of the literature. How we read on a screen or paper and how much we retain of what we read depends on personal history and experience and habits. And perhaps to the well-wired mind the newspaper might seem intolerably limiting.

It’s not. I think we should have some control over the pace with which the world, and the news, comes at us. And look: since neither screen nor paper will ever do better than to offer a simulacrum of “real life”, my daily paper brings its own simulacrum in its unique way, its own fantasy of what the world is like. I relish reacquainting myself with it each morning, at least for as long as I can.

Yes, yes, yes. When my day REALLY begins I will peek at my phone or flip open my laptop … all of my illusions destroyed, replaced by others, and at a much more frenetic pace. Until the next morning when I sit with my steaming cup of java, in my plumped-up chair … reading about the “real world” held in place so I can get a good look at it.

COMING UP NEXT …

Not a “Part 2”, really. More a continuation of the debate now erupting about the failure of government regulation to social media platforms, the failure of the tech giants to police themselves, the dubious/ineffective mega-fines accessed against the tech giants for harmful content and activity, and the roll-out of new government laws to criminalise certain online activity. HINT: don’t rely on the big institutions that surround you to keep you safe.

Yes, following his post last month announcing a pivot to encryption and away from the newsfeed, even Mark Zuckerberg now calls for more social media regulation, and for removing the judgement of what should be publishable from platform companies. His second judo move in as many months. Brilliant? Yes. Devious? Of course. But a smart move.

Plus a swathe of the world is adopting China’s vision for a tightly controlled internet over the unfettered American approach, a stunning ideological coup for Beijing that would have been unthinkable less than a decade ago. The more free-wheeling Silicon Valley model once seemed unquestionably the best approach, with stars from Google to Facebook to vouch for its superiority. Now, a re-molding of the internet into a tightly controlled and scrubbed sphere in China’s image is taking place from Russia to India, and beyond.

And the technology. There is a whole new world of “shadow commentary” emerging. For example, Dissenter which is a browser plug-in that lets the alt-right, alt-tech world tag discussions to normal web pages that no one else can see, and distribute them … undetected. Just more and more of these “private gardens” as I noted in my commentary above.

The gut issue? Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, IBM, and Apple (the “G-MAFIA”) have us hamstrung by the relentless short-term demands of a capitalistic market, making long-term, thoughtful planning for impossible.

All this and more … stay tuned.

One Reply to “Reflections after the International Journalism Festival: the struggle to deplete the Internet of the oxygen of toxic amplification [LONG READ]”