18 February 2019 (Brussels, Belgium) – So the really hot read last night (or this morning if you did not pick it up late last night when it hit the internet) is the UK Parliament report on Facebook. It is 110 pages and it took me last night and through this morning to read it. It needs a few more reads. It is fascinating. You can obtain a copy by clicking here.

Needless to say coverage of the report has been extensive across social media with a tsunami of analysis, explanations … and more Twitterverse excitement … to come. No less than 14 magazines and ezines will have it as the lead story this week and next week.

There is a lot I want to comment on but herein a few brief points:

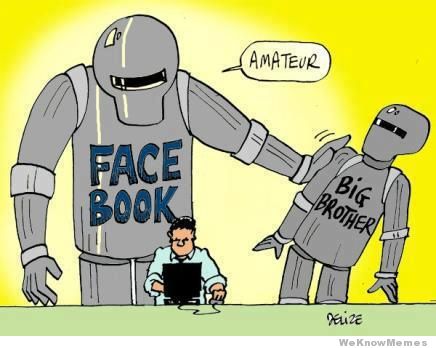

1. I simply love the reference to Facebook as a “digital gangster” (first reference is on page 42). Brilliant. As Stephen Arnold noted on his blog this morning “best two word summary of the document, and its implicit indictment of the Silicon Valley way and America, the home of the bad actors”. Yep, the U.S. has fostered, aided, and abetted a 21st century Al Capone who operates a criminal cartel on a global scale.

2. I am not the first to note this but an interesting point: the need to link “data ethics and algorithms”. Having software identify Deepfakes (you know, those videos and images which depict a fictional or false reality) and dealing with those fuzzy concepts “data ethics” and “algorithm thresholds”. Hmmm … but who’s morality? “Paging Plato. Text message for Mr Plato!”

3. Regulation? Interesting idea but dead (don’t get me going on the GDPR). The suggestions at the end of the report are tepid, at best. And most beyond reach. As noted by the Guardian editorial, the digital cat is out of the bag with regard to data collection, analysis, and use of information. GDPR? Eh. Yeah, regulators might put people in jail. And they might collect fines (that U.S. government/Facebook multibillion-dollar fine settlement over the company’s privacy lapses? Wow. How corrupt is it when you get to negotiate your own fines? They are “negotiating” stealing the privacy of literally millions of people? Nice option to have. And as Katie Fazzani opines at RBC Capital: “short-term stock hit, crimp to bottom line, then it will stabilize”)

Neil Kruger of Demos (an organization that has published detailed analysis on computational propaganda) has said it best: “the regulation of zeros and ones on a global scale in a distributed computing environment? Ha. That boils down to taxes and coordinated direct actions. Will war against Facebook and Facebook-type companies be put on the table. Not likely given the total, world-wide dysfunctional governments we have?” And the paltry level of media literacy. In the U.S. look no further than last year when Congressional lawmakers questioned executives from Google and Facebook about political advertising on their platforms and the political bias of their own employees, and had their lunch handed to them. The poorly phrased questions showed the lawmakers’ complete ignorance about the basics of how a search engine or a social-media site works.

4. And the UK report just confirms what we already know: social media are doomsday machines. Especially Facebook. They distract, divide, and madden. As a result, our social, civic, and political ligands are dissolving.

But the biggie not addressed: no focus on how all of this has destabilized the UK (well, and the U.S.) — countries that have been blasted with digital flows operating outside of conventional social norms, with no way forward. As several commentators noted this morning the UK report is yet another “Exhibit #1” in how flows of digital information decompose, disintermediate established institutions, and allow new social norms to grow in the datasphere.

There are no pleasant answers. In fact, there are NO answers.

If you pull far enough back from the day to day debate over technology’s impact on society – far enough that Facebook’s destabilization of democracy, Amazon’s conquering of capitalism, and Google’s domination of our data flows start to blend into one broader, more cohesive picture – what does that picture communicate about the state of humanity today?

We have surrendered. In today’s digital world, we continue to upload more of our personal information to all of these interwebs in exchange for convenience. We have clothed ourselves in newly discovered data, we have yoked ourselves to new algorithmic harnesses, and we are now waking to the human costs of this new practice.

Current policy debates, however, fail to grasp the systemic dimension of this problem. As such, we hear that some degree of information governance should be necessary to protect us. “Companies should be held accountable for misusing people’s data”. Go to Legaltech in New York or the Computers, Privacy & Data Protection conference in Brussels and you hear the same bullshit: “advanced encryption, improved data anonymity, data ownership and the right to sell it”.

Such strategies only acknowledge the inevitability of commercial surveillance. The lawyers, the regulators, the pundits … they have all surrendered, too. It cannot be stopped.

And the idea of being able to sell your data (an example being the Facebook offer of $20 a month for your data). Isn’t that entirely their own business? The answer is: no, actually, not necessarily; not if there are enough of them; not if the commodification of privacy begins to affect us all. Privacy is like voting. An individual’s privacy, like an individual’s vote, is usually largely irrelevant to anyone but themselves … but the accumulation of individual privacy or lack thereof, like the accumulation of individual votes, is enormously consequential. Accumulated private data can and probably will increasingly be used to manipulate public opinion on a massive scale. Sure, Cambridge Analytica were bullshit artists, but in the not-too-distant future, what they promised their clients could conceivably become reality. No less an authority than François Chollet has written, “I’d like to raise awareness about what really worries me when it comes to AI: the highly effective, highly scalable manipulation of human behavior that AI enables, and its malicious use by corporations and governments.”

Yes, for the thinking person it’s a struggle. As tough as it is given the demands on our time, you can’t be lazy. Reasoning and critical thinking enable people to distinguish truth from falsehood, what is good or. bad, no matter where they fall on the political spectrum. Because media literacy provides a framework to access, analyze, evaluate, create, and participate with messages in a variety of forms. It is needed not only to engage with the media but to engage with society through the media.

Alas, for the majority of our fellow citizens, that ability has vanished. The UK report has multiple references to the lack of digital literacy among users of social media. But I think this guy pretty much sums it up:

Lmao 🤣🤣🤣🤣 pic.twitter.com/frnO3Gat2i

— Hear Mags Roar 🌊🌊🌊 (@Stop_Trump20) February 15, 2019

Final note

At one time I used to think that if Donald Trump not been elected president — reportedly (depending on who you read) by that accidental data wizard Steve Bannon, and/or his hapless colleagues at Cambridge Analytica, and/or a bunch of Russians who managed to use Facebook as it was always intended to be used — the power of Silicon Valley might have remained a niche topic: good for nerdy Twitter banter on the renegade think-tank circuit but pretty useless for anything else. But it was much bigger than that.

If there was one clear message from all the chatter on this UK report … actually all the chatter about Facebook over the last three years … it is that the heady utopia of toxic consumerism propelled by Big Tech has been unequivocally rejected. So the question today is whether (1) Silicon Valley companies will voluntarily impose some structure on their magical platforms and devices – or (2) whether that structure will need to be imposed upon them by the public. Assuming there is any political will to do so. My belief? No way. On either count.

To be sure, populism, nationalism, religious conflict, information warfare, deceit, prejudice, bias … etc., etc., etc. … existed long before the internet. The arc of history does not always bend toward what we think of as progress. Societies regress. The difference now is that all of this is being hosted almost entirely by a handful of corporations. Why is an American company like Facebook placing ads in newspapers in countries like India, Italy, Mexico, and Brazil, explaining to local internet users how to look out for abuse and misinformation? Because our lives, societies, and governments have been tied to invisible feedback loops, online and off. As Neil Kruger said in the quote above the regulation of zeros and ones on a global scale in a distributed computing environment is massively complex.

And there’s no clear way to untangle ourselves.