23 May 2018 (Brussels, Belgium) – In the last several weeks, as we neared the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) enforcement date of 25 May, four remarkable developments:

- A tsunami of “GDPR-consent emails” overwhelming our inbox that in almost all cases was completely unnecessary. My private clients have my detailed memo on the subject but for a very short, excellent brief from IAPP click here. Yet another example of companies (and their lawyers) conflating the GDPR and the ePrivacy Directive rules, the latter having regulated email marketing since 2002. The new ePrivacy Directive rules were to have issued on May 25th to coincide with the GDPR but EU member state bickering continues. More on the ePrivacy Directive in a subsequent post.

- Researchers in the departments of computing and data science at Imperial College London “broke” the new data privacy system that had been approved by the French data protection authority CNIL and commercialized and which CIL said “completely satisfied the full criteria for GDPR”. In fact, the researchers showed how all data anonymization systems can be rendered obsolete.

- Publishers now realize that compliance with the GDPR has provided Google a stance that will further consolidate its position as the dominant digital advertising player, due to the poorly worded Regulation.

- The European Commission has announced that it will launch infringement procedures against countries whose data protection offices are not GDPR-ready.

Oh, beware the things we wish for.

All of these points I have detailed in my private client briefing notes this month. In fact, if you have attended any of the multitude of GDPR corporate counsel/corporate compliance workshops or IT/information security events you know this. No, not the legal technology events and e-discovery events whose sole purpose is to scare the crap out of you so you buy their services and/or technology. I mean the real GDPR events. You need to go to events like InfoSecurity Belgium (each country has one), or the Internet Area Working Group (IAWG) which is a body of systems administrators that acts primarily as a forum for discussing far-ranging topics that affect the entire internet area. The GDPR adds new requirements and layers for documenting IT procedures, and performing risk assessments, and the IAWG really worked me through the GDPR “plumbing”. Or attend the Varonis or Check Point Software or IBM technical unit presentations which basically take a look at your company’s internal data management processes vis-vis how GDPR will influence them.

In the coming month or so I will provide a short public briefing note on points #2 and #3 above. For this post, I will focus on point #4 because it goes to enforcement … and Max Schrems.

And another big shout out to Cronycle who I have mentioned numerous times before. They have been issuing monthly reports on the General Data Protection Regulation, collecting and analysing Tweets and the attachments to those Tweets. Over the month of April alone I was able to analyse 535,118 tweets – equivalent to a roughly 50% increase on March’s GDPR reports – which Cronycle sets up as clusters so I could track who were the big influencers, who was leading the conversations around GDPR, who was referenced the most, what were the top articles and where were the influencers located. For instance, unsurprising that three European capitals (London, Paris, and Madrid) continued to dominate the conversation, due partially to the fact they have extremely vocal and forward-thinking information commissioner’s offices (ICO, CNIL, and AEPD respectively).

Using an e-discovery review platform I could then set up a searchable “keyword/key pic” database and filter for “keys” in any Tweet or article: body text, title, sub headings, photo, graphic, etc. Ah, technology!

GDPR: God, what a mess!

I have had the opportunity to interview Max Schrems twice, and my media team interviewed him last month at the IAPP Global Privacy Summit in Washington, DC (the source of the video clip below). I was in the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg in October 2015 when the judges ruled on “Schrems I” that transferring data to the U.S. under Safe Harbor was now illegal, which eventually gave birth to the Privacy Shield. At the time Max said:

The central problem of sending data to the US can only really be solved if the country adds more judicial oversight of its surveillance. That is, I think, not going to happen in the next 10 years. But I think that question will be raised. It is very similar to the debate over who has jurisdiction in space or international waters. You’d need to come up with some rules for the internet and we all know how difficult that would be.

As regards the GDPR, he and I are on the same page on a number of points. He was the first person I met who had actually read the entire Regulation, including all the Appendices. He encouraged me to do so, and I did. Although I had help. Over the last few years I have befriended a number of Commission personnel who were involved in the drafting of both the GDPR and Privacy Shield so I was able to understand the intended structure of these directives … and where and why they went askew.

Here is a clip from our interview with Max wherein he chats about the fallout from the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica imbroglio, the pushback on the GDPR process rolling out, will GDPR be enforced, and his new organization NYOB – a new type of appropriately resourced non-government organization (NGO) permitted under the new GDPR which many believe will be the key to fulfilling the GDPR’s promise of enhanced privacy rights. I full describe NYOB later in this post:

Max and I can agree on the following:

- The law is staggeringly complex. After three years of intense lobbying and contentious negotiation, the European Parliament published a draft, which then received some 4,000 amendment proposals, a reflection of the divergent interests at stake.

- Corporations, governments and academic institutions all process personal data, but they use it for different purposes. They pummelled the Parliament and the Commission with comments (directly and via a panoply of lawyers and lobbyists).

- The big reason for the regulation’s complexity and ambiguity? The drafters mixed apples and oranges. What are often framed as legal and technical questions are also questions of values. The European Union’s 28 member states have different historical experiences and contemporary attitudes about data collection. Germans, recalling the Nazis’ deadly efficient use of information, are suspicious of government or corporate collection of personal data; people in Nordic countries, on the other hand, link the collection and organization of data to the functioning of strong social welfare systems.

- And so you get unintentional ambiguity (representing a series of compromises) and intentional ambiguity (it skirts over possible differences between current and future technologies by using broad principles). So it promises to ease restrictions on data flows while allowing citizens to control their personal data, and to spur European economic growth while protecting the right to privacy. That’s the pitch, anyway.

But as Max noted, those broad principles don’t always accord with current data practices:

The regulation requires those who process personal data to demonstrate accountability in part by limiting data collection and processing what is necessary for a specific purpose, forbidding other uses. That may sound good, but machine learning, for example — one of the most active areas of research in artificial intelligence, used for targeted advertising, self-driving cars and more — uses data to train computer systems to make decisions that cannot be specified in advance, derived from the original data or explained after the fact.

NOTE: I will return to machine learning in another post. At the recent GDPR/AI summit in Germany, it was a major talking point (read: headache).

And as I have written before, we will see (we are seeing) the development of two types of data companies:

- those who will actually try and meet GDPR requirements, and may even extend GDPR protections globally

- those that bifurcate codebases and policies because their business model relies on data overreach and lax regulation

So in its purest sense, the GDPR is a triumph of pragmatism over principle. What has emerged is a framework that maintains the basis of data protection and adds additional protections, but which falls short of its original promise. While establishing some important innovations, the GDPR could never be described as a ground-breaking instrument for 21st Century protection of rights. Result? The Regulation became a creature of consensus. Much of the detailed enforcement structure was stripped out during negotiations, ceding enforcement powers to the member states. And it left a lot of wiggle room. Taking a broad view, I doubt absolute compliance is even possible.

GDPR enforcement? We’re working on it.

As of this week, most EU states are not ready to enforce GDPR, either by not adopting the required legislation or by not being fully staffed – or both:

- Eight EU states that said they are not ready to fully enforce the GDPR this Friday and will need “at least a year”. They are: Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Malta and Slovenia.

- Several said they “expect” to be ready by sometime in June: Italy, Latvia, Portugal, Romania, Spain, and the United Kingdom.

- Only Austria, Croatia, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Slovakia and Sweden said they will be ready and have their national acts passed by 25 May.

- No word from: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Luxembourg, and Poland.

The European Commission response? Threaten to launch infringement procedures against countries who are not GDPR-ready. Said one German data privacy regulator:

These Commission people are idiots. As if EU member states have the resources/manpower to deal with such an infringement action. No country will blame itself. You think two years was enough time?! In Germany, for example, even the government does not know all provisions relating to data protection set out in thousands of German legislative acts. We’re still researching and we have the manpower. Pity the poor member state that does not.

GDPR: the costs of enforcement

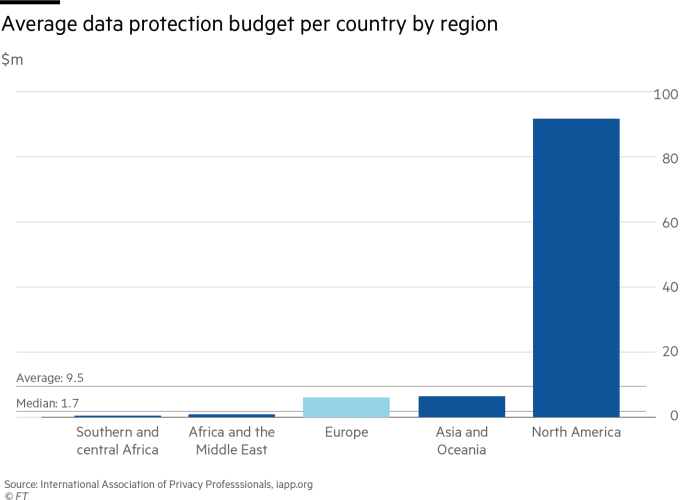

The costs to enforce GDPR have long been an issue. As early as 2015 Jacob Kohnstamm, former chairman of the Netherlands’ data protection authority, was warning that organizations breaking the privacy rules faced “little chance of being caught”. Given his organization’s budget to do investigations, “the chance of having the regulator knock on your door is less than once every thousand years”. The resources available to most European DPAs’ budgets are still a fraction of those in North America — and have only risen by about a quarter on average across the bloc in response to the increased demands on them that GDPR represents.

At the Global Privacy Summit in D.C. last month, IAPP had circulated this graph which the FT reproduced in their GDPR review (and kindly allowed me to republish):

Even Giovanni Buttarelli, the EU’s European data protection officer, warned in a speech last year that the EU regulators were outgunned:

The number of people working for regulators in the EU – about 2,500 – was not many people to supervise compliance with a complex law applicable to all companies in the world targeting services at, or monitoring, people in Europe. That’s peanuts compared to the lawyers and lobbyists in Brussels and Strasbourg.

Any regulation is only as effective as the authorities that enforce it. The twist in the GDPR’s fate is that most of the member states data protection authorities (DPAs) remain ill-equipped, under-resourced or unmotivated. Many DPAs in the past have been too biased or lazy to conduct meaningful investigations. And it is way too early to see whether DPAs can change for the better. But based on informal meetings with a few DPAs in Paris and Rome over the last few weeks and the end-of-year meeting of the International Conference of Data Protection & Privacy Commissioners, a few things look certain:

- DPAs have freely admitted they are understaffed to enforce GDPR and it’s going to take a long while for regulatory authorities to conduct their investigations.

- Expect regulators to target “symbolic cases” … and expect calls that such enforcement is arbitrary and unfair, and ripe for litigation.

All of these DPAs told me they needed more staff on better pay if, as regulators, they are to effectively enforce GDPR. In Ireland, after a boost in government funding, the Information Commissioner’s Office will increase headcount by a third to about 700 by 2020, but other DPAs and companies across the bloc are fighting to hire the trained staff they need. And it takes time to build staff. Said one DPA:

Look, we have a mind boggling, complex, poorly written directive coupled with an equally mind boggling social media culture. We have started more investigating of social media companies and elections and their data retention and use, and we are really trying to create a “proactive” investigative culture. But you are talking about a whole new approach that needs to change in Europe. This stuff is not a blood sport like it is in America.

It has certainly added a nice bump to the employment market. Besides my media company, I own a job listing service for the compliance/ediscovery/legal technology industries and we’ve seen a 52% increase in all sorts of data privacy positions in the private sector, plus the public sector — both sectors looking for litigators, criminal lawyers, staff with investigative experience, social media experts, etc.

And this is also creating issues far beyond cost. Under GDPR one authority will take the lead on cases such as data breaches and related issues rather than the current situation where a company can face multiple legal challenges from regulators in different EU member states. In theory, GDPR prohibits “forum shopping” by companies keen to choose their preferred regulator, and objective criteria should govern who leads on specific cases. So using everybody’s favorite example, Facebook would be the Irish DPA’s responsibility, given its central administration is in Ireland, its terms of service are associated with its Irish entity and it has a substantial data protection and privacy team in Dublin. For companies such as Google, which provides services through its global headquarters, regulation will depend on where cases are brought in Europe. This will make it less clear which regulator has oversight over the company’s data use and privacy practices.

But … the grey areas. Advertising technology businesses that harvest data from third-party websites may have to seek consent from users. Google has attempted to deal with this by defining itself as a “controller” of data under GDPR when handling third-party information. But the designation has been resisted by publishers which will have to seek consent to share information with Google, raising concerns among their own users. This is becoming a huge GDPR issue and will be addressed in a subsequent post.

Enter Max Schrems …

For many DPAs, enforcement may fall to folks like Max Schrems and the new, well-funded organizations being formed. Many think the GDPR on its own will fail to deliver better data privacy rights enforcement even though the GDPR gives new powers to them, due to the issues I noted above: lack of resources, expertise and initiative to uncover and prosecute legal violations.

As I noted in a longer, previous post, the GDPR codifies the right of consumer associations to sue for breach of data protection law. Max Schrems has formed one such organisation and there are scores of others being set-up.

His entity is called “NOYB – European Center for Digital Rights”, or simply NOYB (from the colloquial “none of your business”). It has raised at least 300,000 Euros (£264,000, $373,354) from a Kickstarter campaign which was enough to found the organization and get the ball rolling. Schrems hopes to eventually raise €500,000 in total. It will operate through “a strategic choice of informal warnings, legal complaints, model lawsuits and different forms of collective redress” to fight for netizens’ rights.

The idea is a good one. Although the GDPR gives citizens of European Union member states unprecedented control over their privacy and new options to claim their privacy rights, few individuals have the knowledge or financial resources required to do so, either in court or through DPAs. Entities like NOYB aim to push regulators to enforce the laws by bringing strategic litigation against companies.

Many of the NOYB funders are anonymous individuals, but it has attracted €25,000 from the City of Vienna, and funds from the U.S. organizations Mozilla and Epic. It will start with the “easy issues”, as listed by Max:

- whether a company correctly obtains consent

- does a company allow a user to opt out of data collection

But then it might examine the more complex issues such as “legitimate interest”:

- what does it mean to obtain or keep data for a reasonable purpose?

- how long should CCTV recording databases hold video?

- what data are legitimate for a credit-rating agency to collect?

NYOB also hopes to build relationships with technologists who will be able to track how data are being used. Tech companies often gag employees with non-disclosure agreements but a growing number of former staff want to expose how these companies operate. So Schrems hopes to set up a “privacy bounty” to encourage whistleblowers like Wylie from Cambridge Analytica, who better understand how the systems work and often have the leaked documentation to prove it.

And he’s not waiting. NOYB will be ready to file the first privacy complaints on May 25, the day GDPR comes into force.

CONCLUSION

Yes, I am a cynic. I see lots of issues. What the regulation really means is likely to be decided in European courts, which is sure to be a drawn-out and confusing process. Consider the aspect of consent, which is one of the main pillars of data protection rights. True, the GDPR makes a distinction between “unambiguous” and “explicit” consent, but the difference between the two remains unclear. And Facebook and Google are having a field day with that, as you have probably read. They force you to take their options but they are following the (ambiguous) GDPR “letter of the law”. To be revisited, for sure.

Or the comments at the Munich Security Conference this year which had one session that addressed GDPR privacy from a national security perspective. Presenters opined that the new GDPR changes may make it more difficult to track down cybercriminals and less likely that organizations will be willing to share data about new online threats. So expect governments to find a need from time-to-time to push the “national security exemption” button provided by the GDPR, and the Privacy Shield.

Many of the GDPR’s broad principles, though they avoid references to specific technologies, are nevertheless based on already outdated assumptions about technology. Data portability? I think it’s clear the drafters imagined some company that has your data physically stored somewhere, and you have the right to take it out. But in the era of big data and cloud services, data rarely exists in only one place.

Still, the GDPR is not a lost cause. There is no question that organizations processing personal information are now on notice that they must lift their game. There appears to be consensus – even in Silicon Valley – that use of personal data requires a higher level of due diligence than in the past. Controllers and processors (both of which are now equally liable) need to think carefully about what data they have, where it is located and whose eyes are on it. In essence, this requires a more scrupulous audit and some clear thinking about risk. In many respects, this environment ushers a more systematic approach to handling information. This gets to the whole “information governance” mantra of the e-discovery community.

Yes, we do need rules about data. But legal frameworks, particularly when they are long, complex and ambiguous, can’t be the only or even the primary resource guiding the day-to-day work of data protection. If the ultimate goal is to change what people do with our data, we need more research that looks carefully at how personal data is collected and by whom, and how those people make decisions about data protection. Policymakers should use such studies as a basis for developing empirically grounded, practical rules.

As Alison Cool, a professor of information science at the University of Colorado, said it:

In the end, pragmatic guidelines that make sense to people who work with data might do a lot more to protect our personal data than a law that promises to change the internet but can’t explain how.