2 May 2018 (Paris, France) – One of the enormous subjects we tackled at the International Journalism Festival a few weeks ago was how Western democracies that were once reliable defenders of human rights have been consumed by a nativist backlash, leaving an open field for dictators and demagogues. Populist politicians tend to offer superficial answers to complex problems, but there was this (overly?) optimistic view by Festival attendees and speakers that broad swaths of the public, when reminded of the human rights principles at stake, can still be convinced to reject the scapegoating of unpopular minorities and leaders’ efforts to undermine basic democratic checks and balances. What’s needed, many said, was a principled resistance rather than surrender – a call to action rather than a cry of despair.

Granted, there are very real issues that lie behind the surge of populism in many parts of the world. Globalization, automation, and technological change have caused economic dislocation and inequality. Fear of cultural change has swept segments of the population in Western nations as the ease of transportation and communication fuels migration from war, repression, poverty, and climate change. Societal divisions have emerged between cosmopolitan elites who welcome and benefit from many of these changes and those who feel their lives have become more precarious.

And so demagogues exploit the traumatic drumbeat of horror to fuel nativism. Addressing these issues is not simple … especially when it is so easy for populists to respond less by proposing genuine solutions than by scapegoating vulnerable minorities and disfavored segments of society. And we know just how far such dark impulses can lead.

In fact, part of my crew was in Washington, D.C. last week completing some filming for our post-Festival series and they had an opportunity to look at that very thing: where dark impulses can lead. The following is their guest post.

Catastrophe anticipated: Germany, 1934

Project Counsel Media (Washington DC)

2 May 2018 (Rome, Italy) – “He who returns from a journey is not the same as he who left”. That’s according to an old Chinese proverb. The three of us travel constantly due to our work. But we are fortunate not only because we love our work but because Greg entitles us to incorporate into our travel schedules time off to create an “educational vacation” into every travel assignment, if we feel the urge.

This was certainly the case last week when we had the opportunity to visit the new exhibit “Americans and the Holocaust” at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. None of us had been to the Museum before so it was a perfect opportunity. Little did we know how it would jive with our trip to the Festival in Perugia.

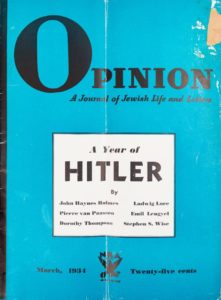

In March 1934, a collection of North American thinkers from the religious (Rabbi Stephen Wise, Unitarian Rev. John Haynes Holmes) to the journalistic (Dorothy Thompson, later the first U.S. correspondent to be ousted from Nazi Germany) gathered to observe a yahrzeit, a memorial of loss, marking the first anniversary of Adolf Hitler’s ascension to power. They met in the pages of Opinion: A Journal of Jewish Life and Letters, a then-monthly magazine (that graphic at the top of this post is the cover page of the issue) that, these days, is all but forgotten.

But read today, 84 years after their publication, the essays still crackle with anger and eerie prescience. Terror had come to Europe, particularly for the continent’s increasingly disenfranchised Jews. With the resurgence of populism and xenophobia around the world today, reading how early 20th-century authors analyzed the dangers posed by that era’s demagogues – long before their terrible plans actually played out – offers some insight into the present moment.

One of the organisers at the exhibit noted there tends to be a misperception in the general public today that Americans did not have any sense of the threat of Nazism as it was unfolding, and just the opposite is true. The monographs printed in Opinion eloquently reinforce that point. We discovered even more such history at the museum. How little we truly know of the past.

And while the original Opinion can still be found in the Library of Congress, the extraordinary foresight of its writers is rarely, if ever, mentioned in the myriad histories of World War II. The anniversary edition reproduced above can’t be found online. That is unfortunate.

Why? Just a snippet we photographed from the exhibit material. This is Dorothy Thompson (then a correspondent for several major U.S. publications) writing about conditions in 1934 Germany:

Law does not govern. Force and the arbitrary and unchallengeable decisions of a small oligarchy, made from day to day, by small decisions, govern. Their decrees are the law. And impossible to challenge.

She and the other writers would anticipate:

- Hitler’s Anschluss of Austria

- the coming war between fascism and democracy

- the degradation and excising of – as well as attempt to exterminate – an entire ethnic group, Jews, from German society

- and they worried, too, about the potential export of Germany’s racialized system of citizenship.

And that is why it is so unfortunate these writings cannot be found online. Because though these pleadings for a prompt and rigorous response to demagoguery went unheeded, the essays contain lessons for addressing current crises. Hitler’s racialist totalitarianism was, in retrospect, an obvious abomination. But given today’s rising anti-immigrant sentiment, populism, and disenchantment with democracy, it is ever more important to remember just how far such dark impulses can lead.

Nothing is inevitable in history. Except of course, sooner or later, the mortality of every civilization and system. And we know that America’s time will come. In the short history of humanity, no democracy or republic has survived. In the short term alone, 90 per cent of democracies created after the fall of the Soviet Union have now failed. Without trying to be too dramatic, perhaps this is the beginning of the end for America.

Right now, as journalists, we are trying very hard not to concede defeat, but perhaps the secular church of liberal globalism has reached its apogee. The global balance of power has certainly tilted away from governments committed to human rights norms and toward those norms of indifference or, more ominously, actively hostile to them. Into the latter camp fall, most obviously, China, Russia, Turkey, the Philippines, and Venezuela. Plus a few countries in Europe.

But more forbidding is that the powers that can speak against that camp have withdrawn from the struggle (the United States), or are shouting into the wind (France). So while we struggle not to concede defeat, we expect to see the moral consensus continue to splinter, with no reason to believe that the glorified “economic globalization” we all read about will ever entail the “moral globalization” that was expected to follow.

Because democracy depends on cohesive communities, and ordinary virtues, and that presupposes functioning institutions of government, who then have a “symbiotic relationship” with those communities. That is a concept we borrow from Michael Ignatieff who in his recent book The Ordinary Virtues: Moral Order in a Divided World, extolled the virtues of an imperial U.S. as a humanitarian force which he now believes has been extinguished by current political forces.

Society cannot hold without a shared moral compass. The result is a return to a “community” where the particularistic bonds of friendship and family, largely among similar people, revert humanity to the tribal state, the present state in which we live. And there is no democracy in tribal societies, for the rights and needs of the tribe supersede those of the large society.