Part 1 of a 3 part series

25 April 2017 – Many, many years ago I had the good fortune of attending what I call a “masterclass” led by Alvin Toffler. Yes, the celebrated author of “Future Shock” who popularized the term “information overload”. His predictions about the consequences to culture, the family, government and the economy were remarkably accurate. He foresaw the development of cloning, the popularity and influence of personal computers and the invention of the internet, cable television and telecommuting. He envisioned a world “isolated and depressed, cut off from human intimacy by a relentless fire hose of messages and data barraging us.”

But he actually shied away from predictions, saying:

“No serious futurist deals in ‘predictions’. These are left for television oracles and newspaper astrologers. I want my readers to concern themselves more and more with general theme, rather than detail. It is the rate of change that has implications quite apart from, and sometimes more important than, the directions of change.

It was in this “masterclass” that he explained how to synthesize disparate facts and to see the convergence of science, capital and communications and how it produced such swift change, creating an entirely new kind of society.

I have tried to apply that to my reading and writing. It is not the numbering and storing of the dots, but rather the connecting of the dots, and seeing the trend lines.

And so it is with my analysis of technology.

This coming fall Apple will release a new iPhone design. It is touted to be a “BIG” event because Apple has postponed any really new design and kept the 6 design for three years instead of the usual two years. The marking buzz (hype?) says “boy, they MUST have SOMETHING that will REALLY attract attention!!”

But you know what? It is still only going to be just another iPhone. Yes, yes. Apple is working on augmented reality glasses, and bendable glass, and there is much chatter about “a car project”. But when you turn to Apple’s strength … mass-market consumer products … I do not see any of those things immediately important. So queue up the “Innovation is dead at Apple!” stories. And make no mistake, it is a parallel world over there in “Android Land”, too.

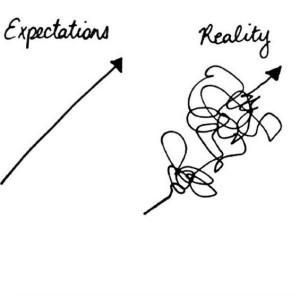

As is true in all technology, we are in a product cycle. New technology of any kind tends to follow an S Curve. I am probably more versed with it in my mobile world, but it certainly holds true in my e-discovery world. Stated simply (courtesy of Ben Evans, mobile analyst extraordinaire):

At first improvement and innovation seems slow as the fundamental concepts are worked out, then there’s a period of very rapid change, innovation and feature expansion, and then, as the market matures and the ‘white space’ is filled in, perceptible improvement tends to slow down. You could see this in cars, or aircraft – far more obvious change in the middle decades of the 20th century than in the first decade of the 21st – and you can see it in PCs or increasingly smartphones now. The PC curve has been completely flat for years and smartphones are now starting to flatten out as well. There will still be substantial improvement in cameras, and in GPUs (driven by VR), but the war is over.

Ben put in a graph as follows:

|

Predictive coding has certainly reached that point. The market has matured and the “white space” is being filled in, perceptible improvement having slowed down. If this past Legal Tech is any indication, attendees were bored out of their socks with “new” releases that were more minor upgrades or backend tweaks. It’s still an iPhone.

Yes, yes, yes. I hear the argument. This is actually a demonstration of market strength. Slowing innovation does not mean weakness but strength: it reflects the fact that predictive coding is in a phase where is it unassailable (thank you, Judge Peck). Yes, it still fails many times in the real world of the document review room as I have chronicled (not the make-believe “perfect conditions” world of the Richmond Journal of Law & Technology, despite its Promethean abundance of promise). But I am not against predictive coding. The fact remains that the white space is being filled in and (most) of the big predictive coding problems are (slowly) being solved. As far as Version 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, ad infinitum … a topic for another day.

Well, yeah, all true. Until the next S curve comes along and resets the playing field.

|

I swear, in the last couple of years, magic started happening in AI. Techniques started working, or started working much better. Especially machine learning (ML). I have been fortunate because it has all been occurring during my neuroscience program at Cambridge and my AI program at ETH Zurich. My best examples: error rates for image recognition, speech recognition and natural language processing have collapsed to close to human rates, at least on some measurements. And exceed human rates, on others. There are still a lot of problems (read my pieceon the recent United Airlines “fight club” episode) especially in e-discovery.

But hey, listen: now you can say to your phone “show me pictures of my dog at the beach”and a speech recognition system turns the audio into text, natural language processing takes the text, works out that this is a photo query and hands it off to your photo app, and your photo app, which has used ML systems to tag your photos with “dog” and “beach”, runs a database query and shows you the tagged images.

It’s magic!!

And just to elaborate a bit more on this “magic”, there are two incredible things going on here which will demonstrate where this stuff is taking us. You’re using voice to fill in a dialogue box for a query, and that dialogue box can run queries that might not have been possible before. Both of these are enabled by machine learning.

But the most interesting part is not the voice but the query. The important part of being able to ask for “pictures with dogs at the beach” is not that the computer can find it but that the computer has worked out, itself, how to find it. Because Apple … or whomever … gave it a million pictures labelled “this has a dog in it” and a million labelled “this doesn’t have a dog” and it works out how to work out what a dog looks like.

Now, try that with “customers in this data set who were about to churn”, or “this network had a security breach”, or “references to fraud or words like fraud” in emails. And then try it without labels (“unsupervised” rather than “supervised” learning) and you see how this builds.

Which is why AI is going to play such a significant role in shaping e-discovery technology in the near future. E-discovery vendors are struggling to stay ahead … and in some cases stay afloat … in a changing industry.

It also explains why e-discovery is moving back in-house. AI is making data analytics faster, more accurate … and more manageable inside the corporate counsels walls. Yes, legal departments are getting bigger, in no small part due to growing legal operations staff. But despite the amount these departments spend on increasing staff levels, far more is being saved through cost-effectively bringing more work in-house. And according to research conducted by long-time friend, legal adviserAri Kaplan, this trend is nowhere more prominent than in e-discovery. Ari recently held conversations with 27 e-discovery decision-makers, composed of corporate counsel, legal operations staff and law firm partners, for his third annual “E-Discovery Unfiltered: A Survey of Current Trends and Candid Perspectives” report. He found that while cost and efficiency drove a significant amount of e-discovery operations in-house, there are more factors and trends at play.

He noted that there were two primary drivers for corporate counsel bringing e-discovery in-house. One was cost, and as Ari noted “you can tie together control with that”. Corporate legal departments wanted to reduce cost and have control of the process.

The second one was the idea of using the technology that they are leveraging for e-discovery to be used for other processes.

I agree as borne out by the huge spike we have experienced on The Posse List job boards for in-house e-discovery positions (legal and technical).

But more importantly by “chat sessions” I have attended at many IQPC corporate counsel events and Georgetown Law’s Advanced eDiscovery Institute. The Georgetown event has a segment called “Behind Closed Doors” and IQPC has a segment called “BrainWeave”. The technology segments are similar: corporate counsel gnashing teeth over what tech works, what tech doesn’t work, what tech they have cobbled together in-house, etc.

One big theme: while organizations view e-discovery more holistically as part of a broader information challenge, they are also turning more to in-house solutions and to vendors not often on the radar like Brainspace , Mindseye and Servient. Said one happy user of Servient:

I have used the “usual suspects” in this business but nobody had what Servient had: metadata as well as text in all analytical judgements so it was even more accurate.

He then waxed lyrical about how “receipt to review” can take minutes, regardless of data volume.

Or several corporations about Brainspace … which I have used myself on several e-discovery/data analytics projects:

Look, we used to have [xxx] do this for us outside the offie. Yes one of the major e-discovery players. And they used [xxx]. But we started using Brainspace and it was incredible, the context/connection it provided. It clearly answers .. for us, anyway … that gnawing issue: when you have unstructured data, how do you actually go about analyzing it? Their concept searching is amazing. And we did it all in house.

I might add he was talking about tens of millions of documents.

Granted. Not everybody can bring e-discovery in-house. There are management issues. You need to have internal familiarity and staffing for proper e-discovery, so there were definitely challenges for folks who don’t have a sufficient team and capabilities internally to manage the entire process. I will address this in greater detail in Part 2 and chat about these vendors in more depth.

|

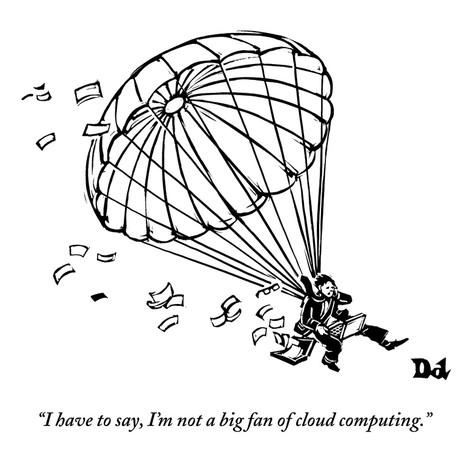

For me, the real “BIGLY” issue in e-discovery is the cloud. Cloud has become important to the e-discovery business and so many vendors are seeking to acquire or partner with cloud vendors. The argument is compelling and the venture capital markets see it. And it is yet another compelling argument why more e-discovery operations are moving in-house.

Think about it. The rapid maturation of cloud-based eDiscovery software has done much to change the calculation of “do I bring it in-house or not?” It used be simple. You had three options: (1) pitch all eDiscovery work to vendors, (2) invest a gazillion bucks in on-premise hardware and software to perform the work internally, or (3) the infamous hybrid model: depending on the nature of the work, some of it is fielded internally and some outsourced to a vendor.

And in Legal Techs of yore, we all heard the drill from vendors: “managed services” – the vendor provides the majority or all of the technology infrastructure, but also personnel who, in the best case scenario, serve as an extension of the firm’s full-time litigation support team (project managers, consultants, etc.). This is a boon for the managed services company, who can charge both for its complex, clunky technology and the highly-skilled labor needed to use it.

But then … BANG! The cloud. Which acts as a force multiplier. Efficiency and scalability are among its hallmarks. So, ideally, firms can do more with less with the right cloud platform. Work that would otherwise have to be outsourced to vendors or managed service providers can be completed with internal resources at a fraction of the time and cost due to these platforms’ ability to automate, or eliminate entirely, many of the steps involved.

Best case which I have seen all across the U.S. and Europe: data processing. In the vendor world, raw data may be collected by the law firm, then sent away to the vendor to be prepared for review. The processed data is then made accessible via a review platform to the firm, or sent back to the firm so that it can be loaded into its in-house review tool. It’s a headache just to read. With a cloud platform, the firm may simply invite its client into its account and have it begin uploading data. Drag, drop, done. The data is automatically processed and made immediately accessible to the firm’s attorneys for analysis and review.

And in my view the battle is between kCura and Logikcull. Call it “The Battle of the Titans”. Or “Microsoft (kCura) vs Apple (Logikcull)”. Clearly kCura had to up its game as it faced the competitive onslaught of Logikcull.

I have heard RelativityOne disparaged as “eh, big deal. It’s an exact clone of their premium software, just plugged into Azures IaaS”. I am not sure what this means for kCura channel partners, but I think there is much, much more going on here. Yes, I am of the opinion that one of the big reasons kCura chose Azure over AWS was the hope that Microsoft would buy them later. But that’s just me musing on this crazy industry. And as a partner in a venture capital company with stakes in three different e-discovery companies, I hear all sorts of stuff coming out of Silicon Valley (and Silicon Glen for that matter).

But since I’m on a roll ….

Why wouldn’t Microsoft buy kCura? Microsoft’s acquisition of document e-discovery software maker Equivio was just one addition (ok, a key addition) to Office 365’s growing portfolio of document management tools for major industry verticals. And the stream of patents they have been acquiring for “methods for organizing large numbers of documents” is just more indication of the move into the e-discovery space.

And surely the sizable Iconiq investment for a minority ownership in kCura assumed a crucial value calculation based on recurring annual revenue. I have no idea what kCura’s recurring annual revenue but given the venture capital industry guesses it is sizable … and that private company multiples are 10-15x forward revenue … my guess is kCura sits at lofty heights.

And if you are Microsoft, who missed mobile entirely, and seeks success in creating cloud-based tools to allow developers to build their own applications on the many AI techniques out there … as does Facebook (I mean come on: what is the newsfeed if not a machine learning application?) … then maybe they have some fun in store for us.

I will cover the cloud in more detail in Part 3. Let me leave you with this:

The data-mining dwarfs in Silicon Valley praise the glories of artificial intelligence and the internet of things, and tell us that machines are the salvation of the human race, technology is the light and wonder of the world. The prophecy is false, but the sales promotion is relentless. Marketers often need a fancy term periodically to sell technologies to large companies. “Big Data” and “Hadoop” were such terms. In the e-discovery world there has been a string: “early case assessment, “managed services”, “predictive coding”, yada yada yada. The mantra: “Focus on your ROI, damn you!”

I do not like that technology is so arranging of the world that it is the thing that thinks and the man who is reduced to the state of a thing. As Lewis Latham recently blogged:

Machine-made consciousness, man content to serve as an obliging cog, is unable to connect the past to the present, the present to the past. The failure to do so breeds delusions of omniscience and omnipotence, which lead in turn to the factories at Auschwitz and the emptiness of President Donald Trump.

why has the cloud is becoming such a major factor in the e-discovery ecosystem?

The terms “SaaS” and “cloud” are thrown around a lot in this space. Cloud computing is an architecture. It’s not a technology. It’s not a delivery model the way most people infer it is. It’s not a browser-based solution. It’s a three-tiered architecture that divides between infrastructure, platform and software. We’ll examine it in detail.