“A world ends when its metaphor has died”

-Archibald MacLeish

“Path in the Fog” by Claude Monet (1887)

28 February 2025 – This is my “birthday week”, a run-up to Sunday when I shall celebrate my 74th year. I’ve read a ton of books this week (7 so far, with a stack still before me) and popped in and out of the “breaking news” headlines and my social media firehose. And I have written a lot.

One of my re-reads has been Charles Arthur’s new book (well, out in 2021) entitled Social Warming, a brilliant analysis of modern social media and communication. Charles (we are long-time friends; first name basis) was the chief technology reporter for The Guardian for 10+ years and he pretty much lays out the way it is: how we actually know our primal instincts kick-in and keep us obsessed with stressful news – and social-media platforms are designed to keep us hooked. Yes, we all wish we could avoid “doomscrolling” or “doomsurfing” or whatever it’s called today, but it is a struggle. Especially with The Orange Clown having such an impact on our lives.

In April 2020, Merriam-Webster added “doomscrolling” to its “Words We’re Watching” list, the same year Oxford English Dictionary named “doomscrolling” its word-of-the-year, noting finance reporter Karen Ho is widely credited with originating the term in October 2018 on Twitter but also noting the phenomenon itself actually predates the coining of the term.

I also re-read Dylan Howard’s history of the COVID pandemic which summarizes the U.S. social media firehose over those 2+ years when it seemed the entire social conversation focused only on two topics: the pandemic and the protests to the pandemic. But, as he notes, the coronavirus didn’t break America. It simply revealed what was already broken. When it hit, it found a country with serious underlying conditions, and it exploited them ruthlessly. Chronic ills – a corrupt political class, a sclerotic bureaucracy, a heartless economy, a divided and distracted public – had gone untreated for years. Americans had learned to live, uncomfortably, with the symptoms. It took the scale and intimacy of a pandemic to expose their severity — to shock Americans with the recognition that its entire society was in a “high-risk” category. And not just from COVID. It is hard to imagine how we would have experienced 9/11 in the era of Facebook and Twitter, but the pandemic provides a suggestive example.

Put that together with the war in Ukraine, the era of Trump 2.0, war that seems everywhere across the world, and climate change ravaging the earth and it is not hard not to think that the world has come to a critical juncture, a point of possibly catastrophic collapse. Multiple simultaneous crises – many of epic proportions, an age of permacrisis – and you now understand all the doubts that any liberal democracy can ever govern its way through them. In fact, it is vanishingly rare to hear anyone say otherwise.

I mean, my God – it was less than 30 years ago that scores of scholars, pundits, and political leaders were confidently proclaiming “the end of history”.

But these folks that had not read Lewis Lapham, George Packer, and Daniel Rodgers who kept saying (and writing) “it never ended”. Those last 3 have been writing for years that we were going through not only geopolitical and economic dislocations but also historic technological dislocations. It would pose a mega-challenge to liberal democratic governance – which, quite frankly, was an understatement. As history shows, the threat of chaos, uncertainty, weakness, and indeed ungovernability always favors the authoritarian, the man on horseback who promises stability, order, clarity – and through them, strength and greatness.

Over 14 years ago Daniel Rodgers laid out a broad hypothesis: the rise of the Internet would lead to the breakup of governments and nation-states, and the emergence of new competitors, thanks to the democratization of consumer choice and the demise of territorial boundaries as a constraint, just as had already begun happening in most private-sector businesses and industries. Rebellion against supranational organizations, sovereign citizen movements, the rise and eventual supremacy of individuated politics and party fracturing (and most every other feature of politics we have seen in the last decade) would flow logically from the consequences of the Internet’s emergence. As the violent assault on the U.S. Capitol unfolded live on television on 6 January 2021 Rodgers avoided a “I-told-you-so” moment to which he was rightly entitled.

We are in fact living through technological change on the scale of the Agricultural or Industrial Revolution, but it is occurring in only a fraction of the time. What we are experiencing today – the breakdown of all existing authority, primarily but not exclusively governmental – is if not a predictable result, at least an unsurprising one. All of these other features are just the localized spikes on the longer sine wave of history.

Hence I opened this post with a quote from the poet Archibald MacLeish because we are at a moment of transition from a rupture in the old patterns of apprehending reality to the construction of a new metaphor when leadership and real thinking really matters most. Rupture can come with a whimper, in which a way of seeing the world finally succumbs to the entropy of the outmoded. Or it can come with a bang, such as the devastating war in Ukraine, and the onslaught of Trump 2.0.

I’ve been wrestling with all of this over this week. On my side-desk sit 8 enormous folders labeled “SHIPWRECK”, short for a long-piece-in-progress entitled “Ruminations aboard the Shipwreck Civilization”.

In them I have shoved 1000s of articles, plus handwritten and typewritten notes, made in various states of intense reflection, disquietude, and hope. When I took out all the folders this morning, and spread them across my work table (which is enormous), alas its contents did not miraculously assemble themselves into an outline – as the mountain of peas, beans, and grains sorted themselves out for Psyche in the Greek myth. But they did remind me how persistently certain realities and urgencies had been haunting me over a period of time. And while Psyche’s task was to separate legume from groat, millet grain from lentil, my task is different – it is rather a work of connection.

But those folders are exploding with content because much of what I write down is merely for my own sanity after event after event after event (after event) explodes across my screen. As more happens I feel we know less because each new fact, each new event makes us forget the earlier blast.

But it is why I write.

Writers imagine that they cull stories from the world. I think vanity makes them think so. That it’s actually the other way around. Stories cull writers from the world. Stories reveal themselves to us. The public narrative, the private narrative – they colonize us. They commission us. They scream at us. They insist on being told. Fiction and nonfiction are only different techniques of story telling. For reasons that I don’t fully understand, poetry dances out of me. I love writing it. But nonfiction is wrenched out by the aching, broken world I wake up to every morning, screaming at me “TELL MY STORY!!”

And it takes a village. John Berger, that most wonderful writer, once wrote: “Never again will a single story be told as though it’s the only one.” There can never be a single story. There are only ways of seeing. So when I tell a story, I tell it not as an ideologue who wants to pit one absolutist ideology against another, but as a story-teller who wants to share his way of seeing. Though it might appear otherwise, my writing is not really about technology or nations or people; it’s about power. About the paranoia and ruthlessness of power, in all os its manifestations. About the physics of power.

In many cases I venture onto ground where I’ve no guarantee of safety or of academic legitimacy, so it’s not my intention to pass myself off as a scholar, nor as someone of dazzling erudition. It has been enough for me to act as a complier and sifter of a huge base of knowledge, and then offer my own interpretations and reflections on that knowledge. No doubt the old dream that once motivated Condorcet, Diderot, or D’Alembert has become unrealizable – the dream of holding the basic intelligibility of the world in one’s hand, of putting together the fragments of the shattered mirror in which we never tire of seeking the image of our humanity.

But even so, I don’t think it’s completely hopeless to attempt to create a dialogue, however imperfect or incomplete, between the various branches of knowledge effecting and affecting our current state.

And it’s difficult. As I have noted before, we have entered an age of atomised and labyrinthine knowledge. Many of us are forced to lay claim only to competence in partial, local, limited domains. We get stuck in set affiliations, set identities, modest reason, fractal logic, and cogs in complex networks. And too many use this new complexity of knowledge as an excuse for dominant stupidity.

It’s the only way I understand writing. It’s certainly the way I’ve been all my life and it’s how every other writer I admire is – a kind of monomaniac. I’m not sure how you can make any art if you don’t treat it very seriously, if you’re not obsessed with doing it better each time.

But now it is time I took a real birthday break.

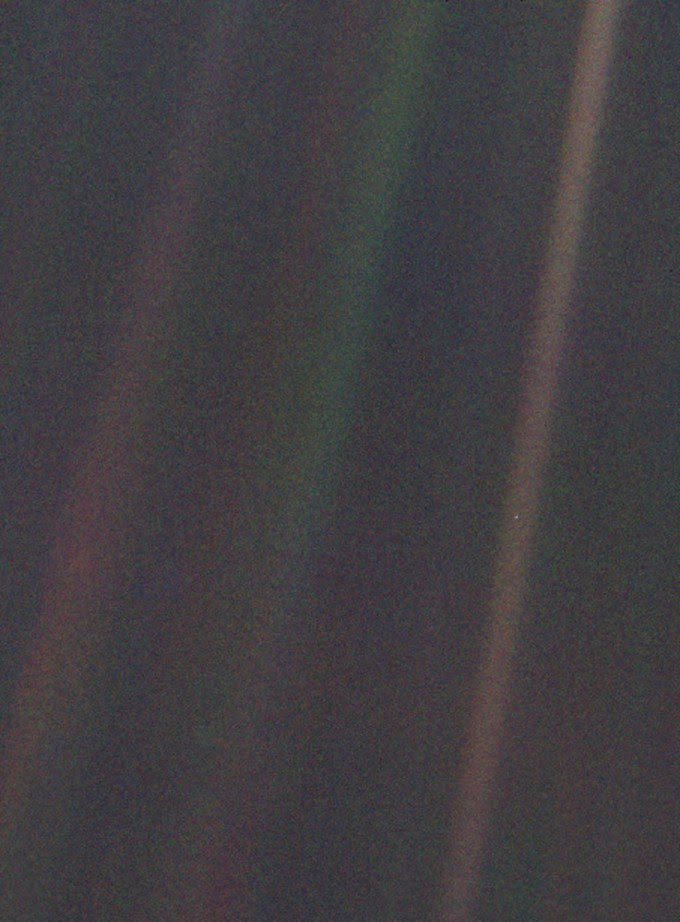

The “pale blue dot” (can you see it?) which inspired Carl Sagan. More on that below.

Is it me, or has the last 2 months been 2 years? It has been a difficult “2 years”. But through it all, I am finding solace, and will do so more intently this weekend, by taking a more telescopic view — not merely on the short human timescale of my own life, but on far vaster scales of space and time.

Last night I watched a documentary about the Voyager spacecraft, and realized I had a book on my shelf that is an intricate history of it, written by several of the engineers who designed it. NASA launched the mission in 1977, with the scientific objective of photographing the planets of the outer solar system, which furnished the very first portrait of our cosmic neighborhood.

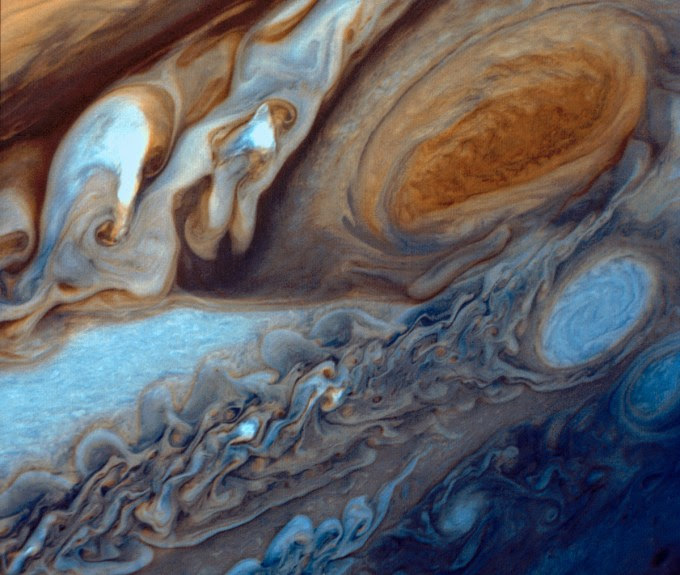

Human eyes had never before been laid on the arresting aquamarine of Uranus, on Neptune’s stunning deep-blue orb, or on the splendid fury of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, the very existence of which dwarfs every earthly trouble:

Jupiter’s Great Red Spot as seen by Voyager. You could fit 3 Earths in it. The Great Red Spot is a persistent high-pressure region in the atmosphere of Jupiter, producing an anticyclonic storm that is the largest in the Solar System. The storm has continued for centuries because there is no planetary surface (only a mantle of hydrogen) to cause friction.

But the Voyager also had another, more romantic mission. Aboard it was the “Golden Record” – a time-capsule of the human spirit encrypted in binary code on a twelve-inch gold-plated copper disc, containing greetings in the fifty-four most populist human languages and one from the humpback whales, 117 images of life on Earth, and a representative selection of our planet’s sounds, from an erupting volcano to a kiss to Bach to assorted music performances.

Carl Sagan, who envisioned the Golden Record, had precisely that in mind – he saw the art and music selections as something that would say about us what no words or figures could ever say, for the stated objective of the Golden Record was to convey our essence as a civilization to some other civilization – one that surmounts the enormous improbabilities of finding this tiny spacecraft adrift amid the cosmic infinitude, of having the necessary technology to decode its message and the necessary consciousness to comprehend it.

But the record’s unstated objective, which I see as the far more important one, was to mirror what is best of humanity back to itself in the middle of the Cold War, at a time when we seemed to have forgotten who we are to each other and what it means to share this fragile, symphonic planet. When the Voyager completed its exploratory mission and took the last photograph – of Neptune – NASA commanded that the cameras be shut off to conserve energy.

But Carl Sagan had the idea of turning the spacecraft around and taking one final photograph – of Earth. Objections were raised – from so great a distance and at so low a resolution, the resulting image would have absolutely no scientific value. But Sagan saw the larger poetic worth – he took the request all the way up to NASA’s administrator and charmed his way into permission.

And so, on Valentine’s Day of 1990, the Voyager took the now-iconic image of Earth known as the “Pale Blue Dot” – a grainy pixel, “a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam,” as Sagan so poetically put it when he immortalized the photograph in his beautiful “Pale Blue Dot” monologue from Cosmos – that great masterwork of perspective, a timeless reminder that included this phrase:

“Everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was … every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician lived out their lives on this pale blue dot”.

And every political conflict, every war we’ve ever fought, we have waged over a fraction of this grainy pixel barely perceptible against the cosmic backdrop of endless lonesome space. In the cosmic blink of our present existence, as we stand on this increasingly fragmented pixel, it is worth keeping the Voyager in mind as we find our capacity for perspective constricted by the stranglehold of our cultural moment.

It is worth questioning what proportion of the news this year, what imperceptible fraction, was devoted to the results of the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics, awarded for the landmark detection of gravitational waves. The single most significant astrophysical discovery since Galileo.

Why? Because after centuries of knowing the universe only by sight, only by looking, we can now listen to it and hear echoes of events that took place billions of lightyears away, billions of years ago – events that made the stardust that made us.

I don’t think it is possible to contribute to the present moment in any meaningful way while being wholly engulfed by it. It is only by stepping out of it, by taking a telescopic perspective, that we can then dip back in and do the work which our time asks of us.

After this gets edited (yes, Craig B, I now have an editor!!) and gets posted, I am off-the-grid for a few days.

Enjoy your weekend.