If Americans are living in a cave of their own making, even if they are offered the benefit of firelight, they might still choose the shadows.

[ The second of my traditional end-of-the-year essays ; there is a link to the first at the end of this post ]

17 December 2024 — Phineas T. Barnum once displayed, in his American Museum in New York City, the corpse of a “mermaid” that was in fact the preserved head of a monkey sewn onto the preserved tail of a fish. He once advertised a large but otherwise extremely average elephant as “The Only Mastodon on Earth”. He once “exhibited” a woman named Joice Heth as the 161-year-old nurse of George Washington (and as “The Greatest Natural & National Curiosity in the World”). He then wrote to newspapers to make a confession: Joice was not, actually, Washington’s nurse. She wasn’t even, in fact, human – but merely “a curiously constructed automaton, made up of whalebone, india-rubber, and numerous springs,” operated by a hidden ventriloquist.

But an autopsy conducted just after her death would reveal that Joice Heth was, indeed, a person, one who was around 80 years of age when she died. Barnum would admit to that, and to the many other tricks he had pulled in the name of public spectacle – or rather, he would boast about them – in a series of newspaper articles and, later, in “Life of P.T. Barnum“, the first of his four books. It was published in 1854, the same year Thoreau published Walden.

Barnum was one of the original creators and commercializers of the pseudo-event, the vaguely real-but-also-not-real thing that, the historian Daniel Boorstin argues, has been the fundamental fact of American culture since the days of Barnum himself. Or, at least, in the years between those days and the days of the mid-20th century.

Boorstin’s book on the matter, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America, was first published in 1962; it was, in its time, a blistering indictment of newspapers and television and Hollywood and the habit they all had of turning mortals into gods. The indictment was so blistering that, when the book’s publication date found Boorstin abroad for a longstanding lecture engagement, a reviewer suggested that perhaps the author had simply decided to flee the country that he had so recklessly libeled.

Boorstin, in The Image, coined not just the term “pseudo-event,” but also the epithetic descriptions “people will be famous just for being famous” and “well-known for well-knownness”; he was, it would turn out, an extremely reluctant herald of postmodernism. While The Image may have arrived on the scene, chronologically, before the comings of Twitter and Facebook and the Kardashians and an understanding of “reality” as a genre as much as a truth, the book also managed to predict them — so neatly that it reads, in 2024, not just as prescience, but as prophesy.

P.T. Barnum understood, intuitively, how many things Americans find to be more enjoyable than reality.

“The image” is, in Boorstin’s conception, both literal (pictures, photographs, etc.) and figurative: a short-hand for images’ cultural primacy, and for an approach to reality itself that is blithely Barnumesque in its assumptions. The image, strictly, is a replica of reality, be it a movie or a news report or a poster of Monet’s water lilies, that manages to be more interesting and dramatic and seductive than anything reality could hope to be.

The image is the spectacle that is most spectacular when it is watched on TV. It is the press conference and the press release — the media event that finds news being created rather than simply reported. It is the logic of advertising, with all its aspiration and transaction, insinuating itself into culture at its depths and its heights. It is the public expectation, even preference, for celebrities who are manufactured, as goods and as gods, because the only thing more compelling than stars themselves is our ability to question their place in our arbitrary firmament.

And, so: the image is fundamentally democratic, an illusion we have repeatedly chosen for ourselves until we have ceased to see it as a choice at all. The image gives rise, Boorstin argues, to a “thicket of unreality which stands between us and the real facts of life”. It is not necessarily a lie, but – and here is the driving anxiety – it always could be.

Boorstin, before his death in 2004, taught history at the University of Chicago and served for more than a decade as the librarian of Congress; his polemic about Americans’ “feat of national self-hypnosis” is, then, fittingly panoramic in its vision. Boorstin traces our “arts of self-deception” to, specifically, the rise of photography in the mid-19th century, and to the public’s attendant ability “to make, preserve, transmit, and disseminate precise images – images of print, of men and landscapes and events, of the voices of men and mobs.”

Boorstin dubs this ongoing state of affairs “the Graphic Revolution” – images, he claims, are to us moderns what the printed word was to our forebears – and he attributes to its influence a dizzying array of pseudo-realities: the cheapening, and thus the wide availability, of printed books and magazines in the 19th century; the rise of the digest as a literary and journalistic form in the early 20th; the churning public demand for news and entertainment that arose from a glut of media sources; the rise of the celebrity as fodder for public conversation and speculation; the advent of image-driven modern advertising, which has encouraged, in turn, “our mania for more greatness than there is in the world”.

What those developments amount to, Boorstin argues, is a cultural attitude toward reality itself that is implicitly, and primarily, suspicious. A few squibs from his book:

On advertising, he noted: “We think it has meant an increase of untruthfulness. In fact it has meant a reshaping of our very concept of truth’.

On art: “As never before in art it has become easy for the great, the famous, and the cliché to be synonymous”.

We are living, still, he suggests, within the sparkle and the spectacle and the fog of P.T. Barnum – whose core insight, after all, was not just that people could be fooled, but that, in fact, they wanted to be fooled.

Barnum set about to make people question not just his exhibits, but also him, as their creator. He paid rivals to publicly declare his antics to be false. He bragged that “the titles of ‘humbug,’ and ‘prince of humbugs,’ were first applied to me by myself”. He knew, long before many others would learn from his tricks, the profound power of epistemic destabilization. He understood, intuitively, how many things Americans find to be more enjoyable than reality.

And, so, the defining figure of the current technological and political moments – Boorstin, in the manner of his contemporaries, assumes that these moments are inextricably bound – might well be a guy who took the desiccated corpse of a monkey and called it a mermaid.

It might also, however, be the many, many people who gave their money to Phineas Barnum in exchange for the thrill of being lied to. Today, living as we do in the shadow of a man who is most readily associated with gaudy circuses, Americans tend to take performance for granted as a feature of political and cultural life. We often assume that, since we ask politicians to entertain us as celebrities do, they will probably pretend like them, as well. Our leaders have, and indeed they are, “public images”. They are concerned primarily with that most ancient and modern of things: “optics”.

But as I look around at AI (especially genAI) and art and images I come back to what I think is Boorstin’s greatest observation:

“We will reach a point where we simply do not know what reality is anymore because we (and others) will create their own. But worse, we won’t seem much to care”.

It was no coincidence, Boorstin noted, that this was slowly building. It was around 1850 – the early years of the Graphic Revolution – that the word “celebrity” came to refer to a particular person rather than to a particular situation.

Nor is it a coincidence that the revealing term “non-fiction” arose a little later: That was a response, Boorstin suggests, to the sudden explosion of fictional worlds that came, via books and magazines, to a democratized and newly literate American culture. The image, the stereotype, the ad, the manufactured spectacle, the cheerful lie … these are, he argues, all of a piece:

“They are evidence of Americans’ constitutional comfort with illusions — not just in our cultural creations, but in our everyday lives. Deceptions are our water: They are everywhere, around us and within us, palpably yet also, too often, invisibly”.

Photography, over its relatively short history, has created new technologies at a rapid rate, leading to new tasks arising and then made unneeded at a relatively rapid rate. As far as I can tell, photography discussions over new technologies have always involved the kinds of discussions we’re now seeing in the context of AI. But when it comes to AI I do think that there are a few things that are interesting to talk about, in particular because they have repercussions beyond photography.

I should briefly preface the rest with what I’ve seen in terms of AI images. I’ve seen a lot of them, but as far as “art” I haven’t seen anything that has a lot of substance.

My graphic artist team and my video team use all manner of AI image tools for my posts and our own work. Always interesting images, but I think AI falls way short in a larger, important sense: it’s not capable of producing something that is coherently speaking of its maker’s vision. I might change my mind next month because I have been invited to London to attend two conferences on art, AI and “vision” at the Science Museum and at the National Gallery of Art. We’ll see.

Creating images in a computer is not new. After all, there has been computer-generated imagery (CGI) for years. My chief videographer has been using these types of tools for 20 odd years, and is now simply giddy with the new AI tools we have taken on board.

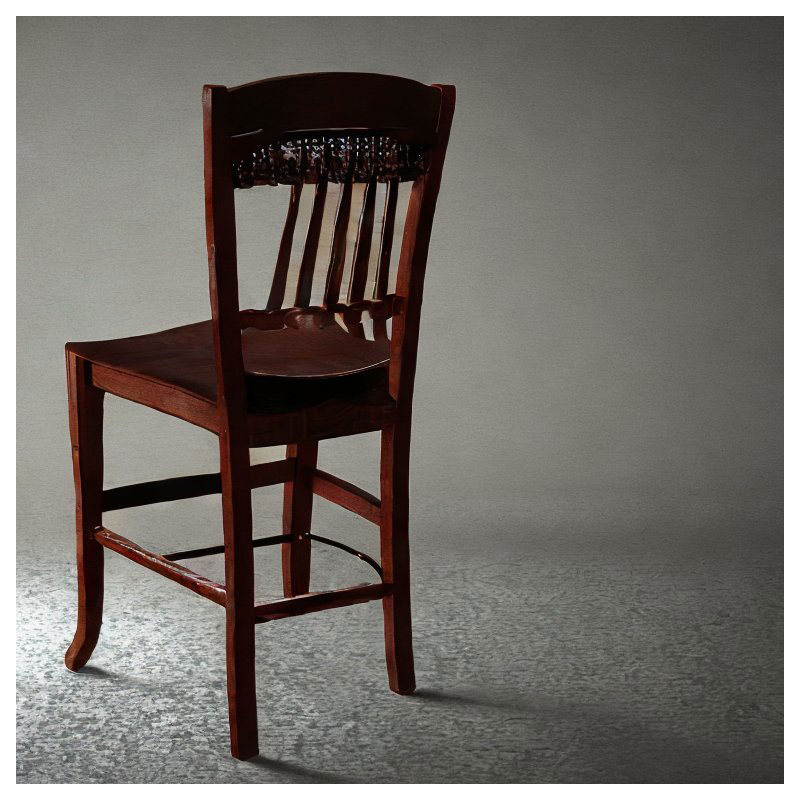

But one thing I do see that is new is that AI image tools offer something completely different: they assemble new images from a database of already existing ones. If you use CGI and you want a photograph of a chair, you will have to tell the computer exactly what the chair is supposed to look like, how it’s lit, etc. With AI, you can tell it “show me a photo of a chair” and it will produce one:

This is one of the images produced by Stable Diffusion when I prompted it with “Show me a picture of a chair”. It looks like a chair, but it’s also wonky. Somehow, the geometry isn’t quite right and neither are various constituent parts. I could play with it, prompt it again, but it was not that important for this article. And there are thousands upon thousands of articles on the internet on how to make AI photographs that pretty much run along the lines of “make amazing, realistic things like chairs!” I am sure advances in technology will make all this child’s play.

Consequently, in an artistic context, artists believe AI photographs need to at least aspire to have artistic merit. By that I mean that their makers have to attempt to contribute to the current artistic discourse. So far, that is not happening. Trying to make funny pictures or trying to prove that you can get realistic looking pictures with AI – that’s too low a bar.

But that then moves us to the more interesting and more important aspect to AI photography. In a loose sense, it centers around the intersection of veracity and believability. Something might not have to be truthful to still be believable. For example, little children believe in Santa Claus. This is the general area where the generation of material, whether visual or textual, ultimately can become/has become very political.

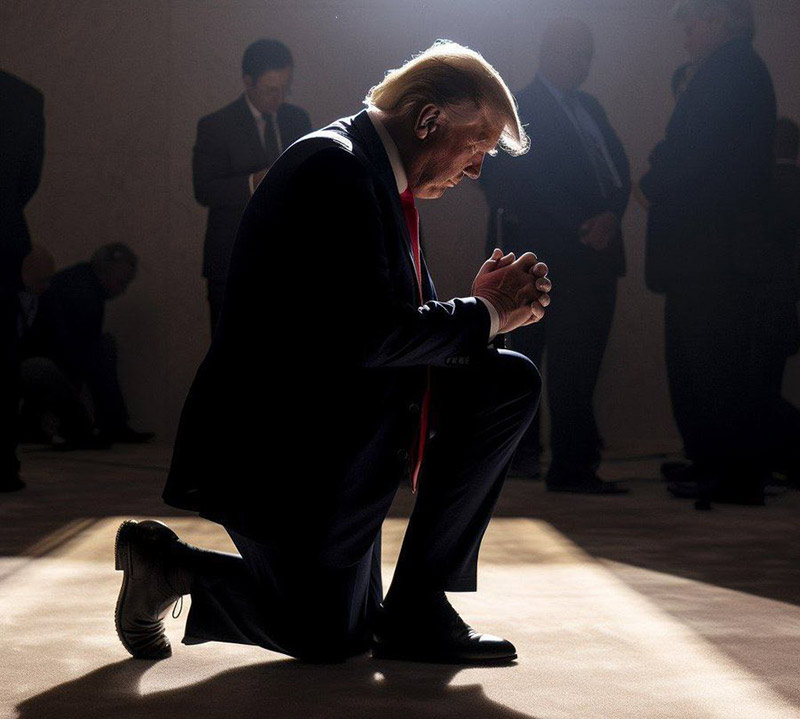

What I simply love about the above AI-generated image is that it was disseminated by the person it is supposed to depict – Donald Trump (created by his media team). If you look carefully at the image, you can see at least two of the standard problems of AI image generators at that time (2023). The hands aren’t right. Furthermore, kneeling with your right knee behind your left heel is very, very difficult. One of my staffers literally tried this. In general, he has very good balance. A swimmer and a biker. But he found it almost impossible to balance the way shown in the image. Versions of the same image created over this past summer were much better.

Essentially, you have to be able to recognize the nonsense if it is embedded in something that looks or reads as convincing. If you’re unable to detect it, then… well, you’ll just take what you see at face value.

On the other hand, most of the people for whom the Trump image was made probably don’t believe any more in what it shows than citizens of the Soviet Unions believed socialist-realist art. It’s hard to imagine that any of those hard-right Christians believe that Trump is religious. But in the image there’s a code that is transmitted. And that code matters, because the image serves to deliver it — instead of what it depicts in a literal fashion.

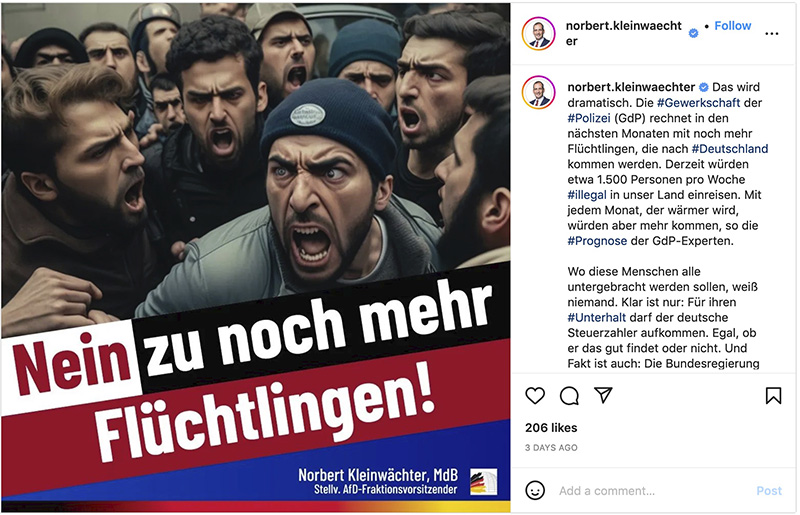

Take a look at this one:

This is an Instagram post by a member of Germany’s neofascist AfD party (it would seem that after some discussion of the imagery, the guy pulled the image). Norbert Kleinwaechter (whose last name ironically translates into “Little Guard” in English) is vice chairman of the party’s faction in Germany’s Bundestag (the German Federal parliament). The text reads “No to even more refugees”. There’s nothing subtle about the image, but obviously that’s par for the course for a party that has a history of producing racism. Note that the fictional person at the leftmost edge of the frame has five fingers.

If you’re not part of the target group, it’s important to be able to read the codes. They might be blatant as in the case of the AfD image, but they can also be more subtle. The visual code often connects to an invisible code that delivers the actual message. Just like in the case of the extremely well balanced Trump, photographic veracity isn’t the actual point.

Semiotics is the study of meaning-making on the basis of signs. Semiotics of photography is the observation of symbolism used within photography or “reading” the picture. The photography critic Liz Wells has a book coming out next year in which she examines realistic, unedited photographs – not those that have been manipulated in any way. And she writes about what “codes” are in those photographs, a totally different context than AI-generated photos. She says it is easy to make fun of images like Trump’s or all the other AI-generated images we see. But if your response ends there, she says, you’re not performing the crucial and more important second step: understanding the codes that are being exchanged. You’re short-circuiting your critical facilities.

Our world. Filled with very convincing nonsense. Images that do not make sense. And that is exactly the larger problem with AI images that we’re about to run into more and more. The problem is not only that images get produced to show something that didn’t happen or doesn’t exist (even though that’s bad enough).

The larger problem, at least in my view, is produced by images that convey nonsensical information even if they were supposed to be truthful and accurate, images that are so convincing that we take them at face value. I suppose you could view this problem as the equivalent of glitch artifacts. But in AI images, apart from wonky hands or other optical problems the more dangerous glitch artifacts are only visible if you have enough background knowledge to detect them.

One of the solutions we have for this problem is a vastly increased awareness of the importance of visual literacy. Specifically, by visual literacy I mean knowledge of the way of looking into how images convey their meaning. We will have to become a lot more aware of how we consume images. This would involve teaching visual literacy in schools and universities (outside of art departments or classes).

In America – that just ain’t going to happen. In America, public education is dying a slow death.

We will probably get used to the fact that almost every image will need to be researched online. If we see an image we might have to look around and see where else it shows up, to infer something about its truth value. Verification tools are becoming more available. But it will be an arms race between AI image-creation and verification tools.

When I was in film school, we learned the camera is not only a tool for generating images. Photography and film “artists” use cameras to generate the pictorial raw materials they need in order to create works expressive of their individual talents and personal visions. The camera is a source of material. The artist provides the form, shaping what the camera supplies into what the viewer sees as a work of art. The content of the artwork – what it has to say to the viewer, the experiences (emotional and intellectual) it prompts the viewer toward – this content comes from the artist, as it does when the work of art is a painting (or other kind of imagined image). The viewer contemplates the artist’s vision. What the artist presents, as her work progresses, is a progressively deeper exploration of that vision.

Simply put, the role of the film artist is to create visual grammar.

When I began my genocide project, I went back to World War I to study its dislocations and the monstrous savagery of industrial warfare, to study how photographers and film makers captured those events. To see how photography worked. They showed a skill set that shone a light upon the raw reality of the world. The indiscriminate power of the lens to record horrendous detail.

But Daniel Boorstin (to take us back to the start of this essay) understood, saw what was coming – long before Jack Dorsey and Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg were born. That “fake news” (a phrase he actually uses in his book) might one day help to win American elections, and that American journalists might soon enough find themselves arguing about whether something concocted can be counted as a “news event”. Or if an image was real or not.

Boorstin knew that our penchant for illusions would change us, inevitably and irrevocably, because he had surveyed history:

“Long before Hitler or Stalin, the cult of the individual hero carried with it contempt for democracy. Propaganda oversimplifies experience, pseudo-events overcomplicate it. Wide-scale adjustments of vision are made necessary by dictators and innovators and performers and frauds — and culminate in a broad reality: that we don’t quite know what reality is, anymore. And, more worryingly, we don’t seem much to care”.

Boorstin took history and philosophy and injected into it a clear-eyed assessment of human nature. He gathered together Barnum and Hitler and Mussolini and David Ogilvy and Marilyn Monroe and FDR and Plato, consulted with them, learned their lessons, and then came to a final, tragic conclusion: if Americans are living in a cave of our own making, even if they are offered the benefit of firelight, they might still choose the shadows.

THE 2024 YEAR IN REVIEW:

ESSAY 1

Donald Trump has the power to dismantle America. He has the tools he needs.