The famous author, who would have been 100 years old today, was best known for his novels and essays. But correspondence was where his light shone brightest.

2 August 2024 — James Baldwin (the playwright, activist, orator, and novelist) was born 100 years ago today. It is no fringe opinion that his work changed American letters forever. He is one of the authors in my small pantheon of writers whom have informed all of my work of whom I have read every book, every essay they have written or published: Italo Calvino, Gerald Durrell, Lawrence Durrell, Umberto Eco, Henry James, Henry Miller, H. L. Mencken and Michel Montaigne. And in the case of Baldwin, every movie he made and (almost) every interview he gave or presentation he made (as available via Youtube).

His book, The Fire Next Time, blew apart my primitive understanding of the central, systemic role of race in American history, and the relations between race and religion. What made Baldwin’s essays effective is that they were testimonial. Giving testimonial evidence about how racism in America has operated in real people’s lives is an effective strategy for connecting with an audience that is otherwise clueless. The book met both the needs of the Civil Rights Movement for publicity, but also an unspoken need of white audiences who did not understand the movement or the lives of the people involved. Although many of the ideas that Baldwin writes about in his essays were not new to black intellectualism, the way they were presented to their audience was.

But like the other authors I mentioned, it was especially through his trove of letters that I really understood the man, and what he was writing about. And I have large compendiums of letters from all of the authors I listed above.

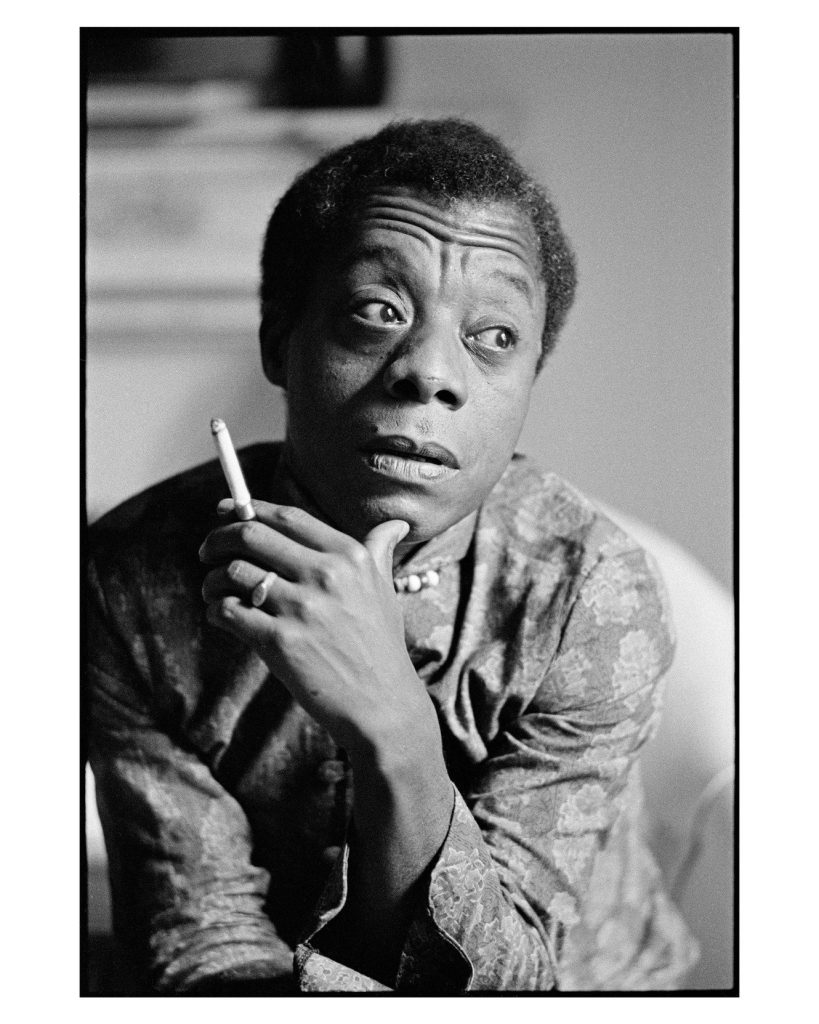

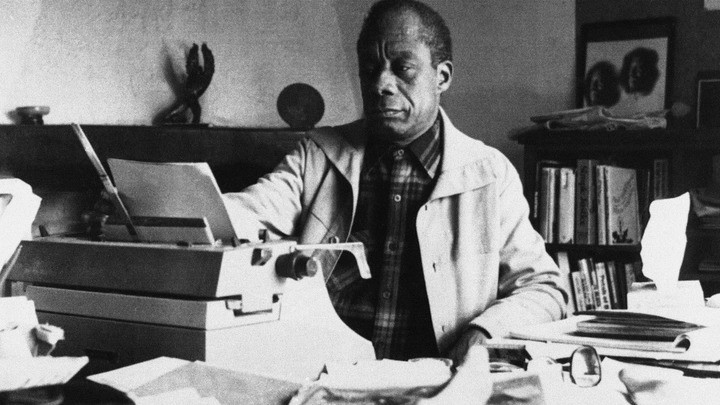

Baldwin’s correspondence was actually the form where his light shone brightest. Towering literary lion, fierce social critic, and inimitable cultural icon James Baldwin opened up a new space for the frank discussion of race, sexuality, and identity in American society. He also left behind a dynamic cinematic legacy, as seen in these portraits that capture his electrifying presence, passionate eloquence, and incisive commentary on everything from art to religion to love to liberation to his most personal experiences as a gay Black man who lived much of his life abroad but who never stopped examining his own complex relationship to the United States.

Earlier today, Vann Newkirk (senior editor at The Atlantic magazine) published an article on the Atlantic blog on that very topic: Baldwin’s letter writing. With his kind permission, his piece now follows, followed by a few of my own concluding comments:

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

“My dear Mr. Meeropol,” the correspondence begins. “Your letter is completely unanswerable because it drags up out of darkness, and confirms, so much.” It was the fall of 1974, and the accolades for If Beale Street Could Talk – his novel depicting a love story interrupted by incarceration – still wreathed all of James Baldwin’s moves. For the moment, he was one of the most famous writers in America. Yet, in the middle of it all, Baldwin took the time to respond to his high-school English teacher Abel Meeropol, an author in his own right who, under the pen name Lewis Allan, wrote the poem “Strange Fruit,” later turned into a song, and recorded by Billie Holiday. The song would become famous.

Meeropol had reached out to his former student, the “small boy with big eyes,” to reminisce on their time in the classroom. His letter recalled that during one exercise, Baldwin had decided to write a winter scene by describing “the houses in their little white overcoats,” a delightful detail that presaged a career full of delightful details. In the humblest possible manner, Meeropol also shared his own work, including his titanic poem, which had by that time become the Black American protest song.

Baldwin proceeded to answer the missive that he had called unanswerable. “I don’t remember what you remember,” he wrote, “but if I wrote the line which you remember, then I must have trusted you.” He continued, “I hope you’ll write me again, and I promise to answer.”

Having read through dozens of Baldwin’s letters, which are mostly housed at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, in Harlem, I know that this kind of promise was not an idle one for Baldwin. The archive is full of his exchanges with celebrities, activists, fans, and fellow literati. Alongside The Fire Next Time, they form an epistolary canon that is, in the main, much less well known than his essays, novels, and plays. But on the occasion of what would have been Baldwin’s 100th birthday, consider that letters were actually the form where his light shone brightest. Baldwin’s correspondence showcases that which still makes him a special read today: a belief in the power of human connection to change the world.

Many letters to Baldwin begin with the same salutation: “Dear Jimmy.” He was approachable – both close friends and new acquaintances used the intimate greeting – even as he prompted a deep sense of respect. Those who’d never written to him before nonetheless felt a certain familiarity, while those who regularly wrote to him remained eager for his approval and love.

This duality is evident in letters from the author Alex Haley, then best known for his The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Haley and Baldwin struck up a close correspondence in the late 1960s, one in which Haley often pressed Baldwin to allow him the honor of becoming Baldwin’s biographer; Baldwin tried to gently dissuade Haley from the endeavor. The two also tried to make plans to adapt Haley’s work on Malcolm X for the stage. One gets the sense in their letters that Haley tried hard to impress his friend. During one meeting, Baldwin complimented Haley’s luggage, so Haley had a set sent to him. (It’s not clear whether Baldwin received the set; Haley acquired the proper address from Baldwin’s assistant, and yet the packages were returned to their sender, without the luggage.)

Haley also felt compelled to share with Baldwin the research that would lead to his most famous work, Roots. “Dear Jimmy,” Haley wrote in 1967. “I went through over 1100 itineraries of slave ships, and I found her, unquestionably – the ship that brought over my forebear Kunta Kinte.” Although Haley would go on to invent much of the purported history presented in Roots, his earnest excitement – and the fact that he’d wanted to share the moment with Baldwin- is a small treasure of the archive.

There are other treats as well. Baldwin often invited his friends, including Haley, to visit during his frequent sojourns in Istanbul. One such guest was the actor Marlon Brando, who had been one of Baldwin’s dearest companions since their college days. Brando came on “a mission which was unclear,” according to Baldwin’s biographer David Leeming, one that saw him hounded by much publicity. Brando abruptly traveled back to the States, leaving behind only a note dashed off on hotel letterhead. “Dear Jim, just had to split,” he wrote. “The press are like flies in the outhouse.”

James Baldwin, ghosted! His international friendships were full of comings and goings—a strange combination of aloofness and yearning. Writing to Lena Horne in 1973, he invited the world-famous jazz singer to a Christmas Eve special he was planning that was to be broadcast for incarcerated people. “I think the show might be important,” he told Horne. But the real prize would be an opportunity for the two to catch up. “Please get in touch with me as quickly as you can,” he wrote. “And please remember dear lady, that this strange solitary distant man loves you very much and will always love you.”

Baldwin was a caretaker within his friend group of Black intellectuals and performers, a role that they treasured in their notes to him. Nina Simone, for whom Baldwin had served as a mentor and confidant, wrote to him in 1977, while he was living in the south of France and she in Geneva. Both were in their own kinds of exile, reeling from disillusionment with the racial order in America. Simone had recently fled America in the face of mounting tax bills and was estranged from her husband, who managed her money. But her sunny letter inviting her dear Jimmy to a series of her shows in Paris illustrated his capacity for lifting spirits. “I need to hear from you man! I’m very homesick,” she wrote. “P.S. I wear your scarf all the time.”

Baldwin wrote to Lorraine Hansberry, to Ray Charles, to Maya Angelou. He was one of the people who encouraged a young Black editor at Random House to try her hand at novels. That editor, Toni Morrison, later bemoaned having to pass on Beale Street, writing in her own letter to Baldwin, “It is so beautiful that I wanted to cover it, touch it, promote it, be knowledgeable about it – you know become an If Beale Street Could Talk groupie.” Baldwin was always encouraging his comrades to create, to continue bringing new work into the world. This propensity took on a special significance after the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. In various letters from this period, Baldwin prayed that his generation of writers and artists might dare to persist.

Even in his private correspondence, Baldwin believed in the power of the word to change the world. Regarding assassinations and grief, he jotted down a letter to then–Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy in 1963 after the assassination of his older brother President John F. Kennedy. Baldwin wrote on behalf of himself, Hansberry, Horne, and Harry Belafonte, who together had met earlier that year with the younger Kennedy to try to push the administration to more openly support civil rights. Baldwin proved as calculating as he was consoling, imploring Bobby Kennedy to fight on in his brother’s memory. “Death, as we know, is in one way absolutely final; in another, as we know, and as human history proves, it affords the greatest of all challenges to the human spirit,” Baldwin wrote. “A number of our most massive achievements have been snatched from the jaws of death – by we, the living, whose burden of opportunity it is to carry forward the work for which our fallen comrades died.” Kennedy evidently took the group’s words to heart, becoming a stalwart protector of civil rights during his tenure as attorney general and an ally of the movement during his ill-fated presidential campaign.

Baldwin frequently endeavored to turn his epistolary power into action – the man loved an open letter. In 1970, as mail from across the country poured into the New York Women’s Detention Center in support of the activist Angela Davis, who was incarcerated there while facing murder charges, Baldwin added his own letter to the torrent. In his missive, later published in the New York Review of Books, the influence of Black Power on his evolving worldview was clear. “We know that the fruits of this system have been ignorance, despair, and death, and we know that the system is doomed because the world can no longer afford it – if, indeed, it ever could have,” he told Davis. “The enormous revolution in black consciousness which has occurred in your generation, my dear sister, means the beginning or the end of America.”

In 1974, Baldwin again hoped to use his letters to indict the system. That year, after President Gerald Ford controversially pardoned his predecessor, Richard Nixon, for Nixon’s role in the Watergate scandal, Nelson Rockefeller – the previous governor of New York and incoming vice president – applauded his new partner’s decision as “an act of conscience, compassion, and courage.” In an open letter he seemed to have wanted published by Newsweek, Baldwin excoriated Rockefeller. “If Mr. Rockefeller judges Gerald Ford’s pardon of Nixon ‘an act of conscience, compassion, and courage,’” he wrote, “then there are American citizens who would like to be informed as to how he judges the no-knock, ‘stop-and-frisk’ laws he, as the governor of New York, instituted in New York State.” Baldwin continued: “This particular American citizen would also like to have described that ‘conscience, compassion, and courage’ which led to the slaughter at Attica,” referring to the 1971 prison uprising that Rockefeller sent police to crush, resulting in the killing of more than 30 men.

Baldwin’s two most famous letters, the two parts of The Fire Next Time, exemplify his masterful use of the form to create intimacy with—and generate empathy in—readers. Their enormous influence, then and now, has inspired an epistolary tradition in the Black literary canon. But I’m most interested in the ways that those same tools inspired Baldwin’s readers in their own lives, and how many of those readers felt compelled to send him letters. Alongside the requests for autographs or photographs are notes that reveal the deeply felt impact of his work on average Americans. “I am just writing you to let you know that your writings have penetrated my being,” one fan wrote in 1973. In 1977, another correspondent wrote that “without reservation,” Baldwin was “one of the five greatest novelists and literatists of this age.” One woman, writing on stationery adorned by a sketch of a rabbit, said that she’d read Beale Street in a single sitting, and that “the last two hours that I have lived in this book have engulfed me with a humbleness that will never leave me.”

My favorite letter in the Baldwin archive, written by hand from a fan in Pittsburgh, regards Beale Street. The writer describes sharing the novel with the man they love, who is incarcerated. “He says he loves all your writing as much as I do,” the letter reads. “And more than that, much more than that, it hasn’t been until I wrote to him about this book that he’s written that he loves me too. It’s like just knowing someone as important and powerful as you are could write seriously about people like us, divided by jails, gave him a new sense of hope, of belief in himself again.” Baldwin’s work may have shaken America’s foundations, but this letter illustrates how his ability to peer into people’s inner lives mattered just as much. He cultivated beauty, even in the bleakest situations, and it often bore fruit.

There are dozens more letters to sift through: love letters, family business, more fan mail, official publishing business, Baldwin’s unusually graceful rejection notes for requests he couldn’t accommodate. In all, they do just as much as Baldwin’s literary works to help explain and diagnose America’s ills. They also help elucidate the ineffable something that makes his work special. Baldwin’s letters closed the distance between past and present, Black and white, prison and the outside, person and person. His elegance is matched only by his humility and care. As with Baldwin’s novels and essays, his letters evince a genuine love for humanity that not even the frustrations and sorrows of the post-civil-rights era could fully extinguish. For Baldwin, the letter was an act of optimism, a bet on the possibility of people seeing themselves in the other.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

There are days—this is one of them—when you wonder what your role is in this country and what your future is in it. How, precisely, are you going to reconcile yourself to your situation here and how you are going to communicate to the vast, heedless, unthinking, cruel white majority that you are here. I’m terrified at the moral apathy, the death of the heart, which is happening in my country. These people have deluded themselves for so long that they really don’t think I’m human. And I base this on their conduct, not on what they say. And this means that they have become in themselves moral monsters.

James Baldwin made this somber observation more than 55 years ago. He says them in the film I Am Not Your Negro, which explored Baldwin’s searing assessment of American society through the lens of the assassination of three of his friends: Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X. It is a film that cruelly shortens time and space between acts of police brutality in Birmingham in 1963 and images of the 2014 protests in Ferguson, Missouri, after the killing of Michael Brown.

It took over 10 years to make that film, but Baldwin put his whole life and body weight into these words, which, today more than ever, reverberate like a never-ending nightmare. With them, Baldwin dissected a story whose roots are deep. He exposed the underlying causes of violence in this country, and he would have continued to do so, year after year, one uprising after another, were he still alive today. And we still don’t get it.

Today, as protests against police brutality and institutional racism continue around the country, it is impossible to hide the scars anymore, the ugly facts, the videos, the overwhelming and systemic negation of human life. That infamous phrase “We can’t breathe!” – cried all the Black men who have been killed – means if they can’t breathe, none of us should breathe, Black or white. These are the terms of the social contract. “It comes as a great shock to discover the country which is your birthplace and to which you owe your life and your identity has not, in its whole system of reality, evolved any place for you,” Baldwin said.

When I Am Not Your Negro came out (2016), people were stunned that it did not cause riots or provoke a banning from the public for being the messenger of such cutting words. The film is based on Baldwin’s 30 pages of notes for a book project called Remember This House, which he ultimately never wrote (he died in 1987), because it was too excruciating to do so. In it, Baldwin expressed profound truths about America that had never been said in such a direct and explicit manner:

I have always been struck, in America, by an emotional poverty so bottomless, and a terror of human life, of human touch, so deep, that virtually no American appears able to achieve any viable, organic connection between his public stance and his private life. …

This failure of the private life has always had the most devastating effect on American public conduct, and on black-white relations. If Americans were not so terrified of their private selves, they would never have become so dependent on what they call “the Negro problem.”

Baldwin’s words are forceful and radical; he punctures the fantasy of white innocence and an infantile attitude toward reality. He understood that there is extraordinary capacity for denial in this country, even when confronted with evidence and logic. His was a deep knowledge of the white psyche, which he thought was marred with immaturity. In this, he unsparingly exposed America’s original sins. First, the genocide of Native Americans: “We’ve made a legend of a massacre,” he said, which is a narrative “designed to reassure us that no crime was committed” and propagated by Hollywood’s “cowboys and Indians” stories. Then, the haunting legacy of slavery: As he said in a famous 1968 interview on The Dick Cavett Show:

“I can’t say it’s a Christian nation, that your brothers will never do that to you, because the record is too long and too bloody. That’s all we have done. All your buried corpses now begin to speak”.

Denial of these sins, he made clear, is a powerful regulatory societal force, as mirrored, for example, in the entertainment industry. He wrote:

“The industry is compelled, given the way it is built, to present to the American people a self-perpetuating fantasy of American life. Their concept of entertainment is difficult to distinguish from the use of narcotics. To watch the TV screen for any length of time is to learn some really frightening things about the American sense of reality. We are cruelly trapped between what we would like to be and what we actually are.”

Other institutions have similarly erased history.

Why can’t we understand, as Baldwin did and demonstrated throughout his life, that racism is not a sickness, nor a virus, but rather the ugly child of an economic system that produces inequalities and injustice? The history of racism is parallel to the history of capitalism. The law of the market, the battle for profit, the imbalance of power between those who have all and those who have nothing are part of the foundation of this macabre play. He spoke about this not-so-hidden infrastructure again and again:

“What one does realize is that when you try to stand up and look the world in the face like you had a right to be here, you have attacked the entire power structure of the Western world.”

And more pointedly:

“I attest to this: The world is not white; it never was white, cannot be white. White is a metaphor for power, and that is simply a way of describing Chase Manhattan Bank.”

Tonight I will escape from my normally pedantic world and re-read The Fire Next Time.