Our memories are made up of so many uneven flagstones. And that’s critical.

28 July 2024 — For those of you that remember these things, the “Proust Barbie joke” in last year’s smash movie “Barbie” happens when a character tells Barbie to spend time in the box that she came from. It comes at the end of the film. She goes into the box and remembers being there before. She comments on the scent being “a Proustian memory”. Will Ferrell, who plays the CEO of Mattel, makes the Proust Barbie joke:

“Remember Proust Barbie? That did not sell well”.

By the memorable ending of “Barbie”, the film’s message about what it’s really like to be a woman in today’s society has been made clear. “Proust Barbie” speaks to the film’s commentary on the patriarchy along with a corporation’s desire to make products that are, of course, profitable. While audiences see various Barbies in both “Barbie Land” and the “Real World”, “Proust Barbie” is not one of them. Mattel never made one. It was the director’s inside joke about self-discovery.

And if you have any familiarity with French literature, then you know Marcel Proust’s magnum opus “In Search of Lost Time“, a book that actually has seven volumes, with “Swann’s Way” the best known and most popular. And even if you are not that familiar with his opus, you most likely know the famous madeleine scene which has slipped into common parlance as it did his tea. The madeleine moment – also known as “the Proust effect” – concerns the ability of memory to be invoked involuntarily when it had been previously blocked.

The concept was (somewhat) repeated in the Pixar cartoon “Ratatouille“:

But Proust’s famous madeleine scene is prefaced by some stage-setting remarks about voluntary memory. After recounting at length how much he missed his mother when, as a child, he was forced to go to bed early at their summer residence in Combray, he seems to recognize how contrived the whole story was:

“The fact is, I could have answered anyone who asked me that Combray also included other things and existed at other times of day. But since what I recalled would have been supplied to me only by my voluntary memory, the memory of the intelligence, and since the information it gives about the past preserves nothing of the past itself, I would never have had any desire to think about the rest of Combray. It was all really quite dead for me”.

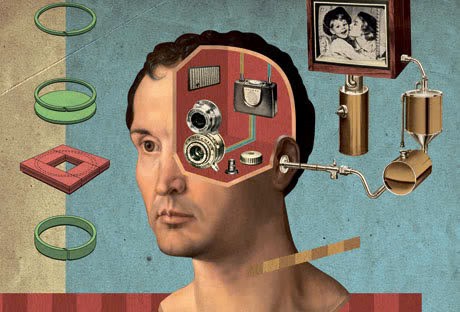

His memories of his bedtime anxieties are also voluntary memories, intellectualized and well-worn through their integration with his sense of himself, and in a certain sense pat and dead, containing nothing about the past and revealing instead the narrator’s present disposition toward what he habitually remembers about his personal history. To get at “the past” rather than merely “information about the past” requires the mediation of what amounts to a magical object:

“It is the same with our past. It is a waste of effort for us to try to summon it, all the exertions of our intelligence are useless. The past is hidden outside the realm of our intelligence and beyond its reach, in some material object (in the sensation that this material object would give us) which we do not suspect. It depends on chance whether we encounter this object before we die, or do not encounter it”.

And just a quick note to readers: years ago I had read bits of “In Search of Lost Time”. But some years back large chunks of it were part of the syllabus in my MOOC neuroscience program at Cambridge University. Since then I endeavored to read all 7 volumes. I have 3 volumes to go.

And so, the magic cookie unlocks for Proust an entirely different level of recollection that purports to be “beyond intelligence” — not something calculatedly recalled because it suits some immediate rhetorical purpose or some long-standing narrative about the self, but something that floods in like raw sense perceptions in themselves, apparently unmediated by our present-moment concerns or concepts:

“All the flowers in our garden and in M. Swann’s park, and the water lilies of the Vivonne, and the good people of the village and their little dwellings and the church and all of Combray and its surroundings, all of this which is acquiring form and solidity, emerged, town and gardens alike, from my cup of tea”.

The profusion of detail is presented as if to prove that the past has become present, that this is no longer motivated story-telling but truth itself pouring out.

But it’s tricky to apply this kind of theory about memory to photographs. Is it so easy to distinguish “the past” from “information about the past” when we have hundreds or thousands of images to provide that information for us? Can a photograph ever be a madeleine, an accidental container for the entire “edifice of memory,” or is a photograph always just turning a moment into information and rendering it “dead” for our future selves?

Of course, some photos seem more effective at sparking Proustian involuntary memories than others – these tend to be the sorts of images that survive by accident, or is a matter of the incidental, accidental details perceivable in more ceremonial, formal images. That is, the aspects of the photo that seem unintentional now are the aspects most likely to trigger this kind of remembering. The more that the original intention of the photo looms over its contents, the less it is able to convey anything beyond that intentionality, that overt and obvious message. This extra, unintended material becomes capable of being more than just “information” because it prompts nostalgic feelings that Proust apparently equates with “the past itself.”

This extra stuff reminds us of all we failed to conceptualize and codify about our experience as it was happening, revealing that it still somehow affected us anyway, shaping us somehow so that we can encounter it later and recognize it intimately without having been able to remember it. The dulled feelings we have about the stuff we deliberately focused on and intentionally photographed and integrated into our personal narrative is suddenly upstaged by this integral background material that emerges as crucially significant because we once took it for granted.

You would think phone camera rolls would be full of this kind of thing, overloaded with photos whose original purpose has dimmed or been totally lost so that they now seem to teem with unintended detail, providing a window into life how it was being lived rather than being staged or performed. But that is not what comes across in this writer’s lament about a disappointing camera roll.

On my flight to the U.S. a few weeks ago, bored by my reading material, I began a deep dive into my phone’s camera roll and noticed something interesting: my way of seeing and capturing the world has actually changed pretty drastically over the last ten years. The “stupid but sweet” snapshots had given given way to something different. There was a new focus, an attempt to present an aesthetic, an idea, an “editorial look” as my wife would say as she also looked (we have shared albums on almost everything). Many of my photos no longer even feature people. Instead, they become dominated by images of myself alone, or empty landscapes. What has replaced the people? Objects.

And especially the sea. Sometimes when I am standing on the beach, staring out at the ocean, watching waves roll in, I will become moved with the inarticulate sense of nature, the sublimity of it all. And even if I have my phone with me, I avoid taking pictures – just enjoying the mental photogenic moment. After 4,000+ photos of rolling seas and sunsets/sunrises over the sea, there are just a few of what I’ll call “artful” shots. Because the sublime is sublime because it exceeds representation, defies it, confronts our puny understandings with phenomena we can’t fully assimilate.

When I chat with photographers about this, I am told part of this shift is attributed to being conditioned by social media metrics to post only what gets likes and circulation, and thus to think of photographing only what accomplishes those aims. Such images typically must be far more purposive, far clearer in their intended message, so that audiences know what idea they are liking.

And even if they were originally obscure, the fact of their circulation and their being liked becomes their message, and that intention can be read back into the image after the fact. The metrics attached to an image mean that it will always unmistakably be “information about the past”: the numbers urge us to understand the entire image in such informational terms, as accomplishing certain amounts of circulation and attracting certain kinds of comments in the network. Algorithms work against the sense of “accidental” survival and unintended affects.

But what is good for social media circulation is bad for involuntary, “real” memory. When images are made to present an idea of the self, they will ultimately fail at preserving the “real self,” because to our future selves, who we really were won’t be a matter of how we tried to show ourselves off but how we were behind the scenes, i.e. the usual “authenticity” ideology: what we intend to do is fakery; what we are despite that is real. From this perspective, our camera roll is embarrassing because it catalogs our efforts to try to be somebody and say certain things instead of our “just being,” somehow already complete and substantial without having any drive or desire to do anything that anyone else would have to notice.

But I am not really on social media much these days so I think my camera roll still resembles a curated archive, as if I were crafting a personal “brand” or “aesthetic,” striving for marketability or commodification. There were many photos of empty places that I thought looked better without people, way too many photos of myself, and a heavy emphasis on the things I consumed rather than the people I loved.

And the problem, of course, is even if you do some naval gazing and disavow the creation of a personal style, or an aesthetic at all, having in/about social media, and the work-life conditions forced upon us (willingly?) under neoliberalism, we have made it impossible not to think of self-presentation as anything but “branding.” And the self-branding impulse changes one’s relation to oneself, so that one tidies up the camera roll to suit a certain image of oneself and eliminates all the sorts of off-brand, unintended details that might later be madeleines.

For a writer – any writer – this mainly appears as a tendency to take pictures of objects (and an objectified version of herself) rather than his/her friends (making objects out of them). The objects are “empty places” that convey marketability or sad efforts to be cool; the friends convey sociality, genuine feelings, life being lived and shared in the moment as opposed to staged for a media economy.

I suppose I am at that age when relations with people are much more important and meaningful than relations with things. But I still write extensively, and in depth, and find photographs helpful in that regard. But the objects that mediate social relations and memories of them, for Proust, are intrinsically accidental, undesigned, “a cookie or uneven pavement stones”, and so taking photographs is an intentional act, a deliberate attempt to capture something. As Proust writes in “Finding Time Again”:

“I realized that it was Venice, all my efforts to describe which, and all the so-called snapshots taken by my memory, had never communicated anything to me, but which the sensation I had once felt on the two uneven flagstones in the baptistery of St Mark’s had now at last expressed for me, along with all the other sensations associated with that sensation on that day, which had been waiting in their place, from which a sudden chance had imperiously made them emerge, in the sequence of forgotten days. In the same way, the taste of the little madeleine had reminded me of Combray. So did those two flagstones in Venice”.

If the “so-called snapshots of memory” don’t communicate anything, what chance do actual snapshots have? Taking pictures of friends may paradoxically make it harder to remember them, harder for their living spirit as it has manifested across time to come through in a rush, as if they are fully present in all their history and complexity all at once. Instead, the photos fragment them into on-demand pieces that are merely convenient for remembering this or that moment as a souvenir, a keepsake trinket on the shelf of memory and not the edifice of memory itself.

Proust’s work suggests how places and things can be more evocative of past experience than more literal and comprehensive forms of documentation (of which his books become ironical examples). A memory consists of feeling rather than information, and information can occlude the feeling. In turning to photographs to remember, we inevitably have to look past what is depicted, see through it somehow, get past the fixed impediment it represents so that what it evokes can seem to breathe. What we want to remember – the feeling – is never in the image.

Which is why, I think, after going through that phone camera roll, I am taking many more photos of friends – to “document” the good times, So the camera roll remains, as it does for all of us, an integrated story of the self – what Proust calls “the memory of intelligence”.

If what seemed the point of making the photograph then seems exactly the same as what one can read out of it now, then its usefulness to memory is extremely circumscribed by that point. But if you can make out what the point of image was or if it has outlived that original usefulness to become something else, it might unfold a vista we couldn’t have expected. It may be that we can never capture what we are trying to capture in an image – and that is precisely why we should take more of them. These photos should always be succeeding at something else.