Ah, Presidential immunity.

The U.S. Supreme Court assumes a more exalted and powerful role in government than any other judicial-type body in other Western countries. It is often said that the Founders’ greatest failure of imagination was in not anticipating the rise of mass political parties, and powerful interest groups, although James Madison (somewhat) foresaw it.

1 July 2024 (Washington, DC) — Whenever I fly back to the U.S. from Europe (I landed late last night) I always try to coordinate my trip back so I can travel with a colleague or long-time contact who I have not had a chance to recently visit, face-to-face. It is usually an 8-1/2 to 9 hour flight so it is nice to have some stimulating conversation.

My companion was a high-level member of the United States Cyber Command stationed in Europe (that’s as far as I will go in identifying him) who I have known for a very long time. He is retiring this year and was returning to the United States to get some papers in order.

We had a long chat that basically focused on:

• Multiple U.S. military bases in Europe are under a heightened state of alert for a terrorist attack against U.S. military personnel or facilities, the alert levels raised due to confirmed intelligence indicating some form of terrorist action or targeting against personnel or facilities is likely.

• The expanding Russian sabotage campaign across Europe in the last 9 months, the so-called gray zone, or “hybrid,” attacks. NATO refuses to formally acknowledge even if these are attacks against NATO member states, because if acknowledged, then NATO would need “to do something”.

• In Europe, even if “the center is holding”, the far right is ascending and will not be stopped.

• The reality is that, after almost 80 years of U.S. leadership, the world has entered a transition phase from hegemonic order to a restored balance of power. And everything has become “transactional”. Like all prior balance-of-power systems, this one will feature global dissent, disharmony, and great-power competition. Yes, such dissent most obviously comes from China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia. But the disruption of global stability during this transition phase comes not only from rising challengers but also from the hegemon itself – the United States.

Each of these merits an entire post (maybe a book?) and I will try to elaborate on each as the summer progresses. But it was one comment he made that caught me off-guard:

“I heard Leonard Leo threw another big party this weekend. Trump probably won his immunity case”.

Those of you who followed my Roe v Wade coverage will remember that Leonard Leo threw a huge party the night before the Roe opinion was announced, assembling all of his anti-abortion friends – celebrating the decision the night before it was announced. Who is Leo Leonard? Chairman of the Board of The Federalist Society, the man who had hatched and then executed a plan to stack the courts with 6 extremist judges. It was Leo who had helped pick or confirm all six of the justices who would, that very next day, announce to the world they were overturning Roe.

I thought about that this morning when the U.S. Supreme Court issued its opinion that former presidents are entitled to some degree of immunity from criminal prosecution, widely seen as a major win for The Donald. The court’s conservative majority – the same 6 which Trump helped create with the help of Leo – found 6-3 that presidents were protected from prosecution for official actions that extended to the “outer perimeter” of his office, but could face charges for “unofficial conduct”.

Note to readers: I read the full opinion and it goes much farther than that. The conservatives ruled that not only is a president immune with respect to his official acts, but also that evidence related to those official acts cannot come into any trial. That eviscerates the special counsel’s entire indictment. So out the window goes the facts that:

• Trump spread false claims of election fraud

• He plotted to recruit fake slates of electors

• He pressured U.S. justice department officials to open sham investigations into election fraud

• He pressured his vice-president, Mike Pence, to obstruct Congress’s certification of Joe Biden’s win.

The ruling was one of the last handed down by the supreme court this term. In waiting until the end, the conservative majority played right into Trump’s benefit and legal strategy of trying to delay any trial as much as possible. Trump’s legal strategy for all of his federal criminal cases – he also faces charges in Florida for illegally retaining classified documents – has been to delay them until after the election, in the hope that he will be re-elected and can appoint as attorney general a loyalist who would drop the charges.

But there is a long history here and I want to revisit a post I wrote 2 years ago, with a little updating.

If you want to understand U.S. political history and the building of The Republic, you need to read The Federalist Papers. I have read them a few times, and quote from them quite often.

My favorite bits are by James Madison – principal architect of the U.S. Constitution and its 4th President. He had spent the year before the Constitutional Convention (1787) reading two trunkfuls of books on the history of failed democracies, sent to him from Paris by Thomas Jefferson. Madison was determined, in drafting the Constitution, to avoid the fate of those “ancient and modern confederacies,” which he believed had succumbed to rule by demagogues and mobs.

That was Madison’s fear:

“In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever characters composed, passion never fails to wrest the sceptre from reason. Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob”.

Madison and Hamilton believed that Athenian citizens had been swayed by crude and ambitious politicians who had played on their emotions. Madison referred to impetuous mobs as factions, which he defined in Federalist Paper No. 10 as a group “united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.” Factions arise, he believed, when public opinion forms and spreads quickly. But they can dissolve if the public is given time and space to consider long-term interests rather than short-term gratification.

The Founders designed a government that would resist mob rule. They didn’t anticipate how strong the mob could become. The polarization of Congress, reflecting an electorate fueled only by ideological warfare between parties and citizens, that directly channels the passions of their most extreme constituents and donors – precisely the type of factionalism Madison abhorred.

The executive branch, meanwhile, has been transformed by the spectacle of Tweeting presidents, though the presidency had broken from its constitutional restraints long before the advent of social media. During the election of 1912, the progressive populists Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson insisted that the president derived his authority directly from the people. Since then, the office has moved in precisely the direction the Founders had hoped to avoid: Presidents now make emotional appeals, communicate directly with voters, and pander to the mob. And now they have the judicial branch firmly behind them.

Twitter, Facebook, and other platforms have accelerated public discourse to warp speed, creating virtual versions of the mob. Inflammatory posts based on passion travel farther and faster than arguments based on reason. Rather than encouraging deliberation, mass media undermine it by creating bubbles and echo chambers in which citizens see only those opinions they already embrace. We are living, in short, in a Madisonian nightmare.

But the U.S. Supreme Court has been slowly, deliberately moving toward this end result for quite some time.

A year after the Trump-inspired insurrection at the Capitol on 6 January 2021, the United States experienced a less obtrusive coup d’état: the hustled retirement of Justice Stephen Breyer, the oldest of the three remaining liberals on the Supreme Court.

The prematurely leaked announcement in late January took Breyer himself by surprise. But the leak wasn’t any more of a breach of constitutional decorum than the insistent lobbying that preceded the reluctant retiree’s decision. Breyer’s liberal allies had the noblest motives for expediting his departure. America’s Supreme Court justices have lifetime tenure, and sometimes that is a literal description: the ultra-conservative Chief Justice William Rehnquist died on the job in 2005 at the age of eighty, and so did his ideological ally Antonin Scalia in 2016, aged 79.

More recently, the court’s indefatigable liberal standard-bearer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, died in post aged 87, a mere six and a half weeks before the 2020 presidential election. Had Ginsburg lived four months longer, Joe Biden would have been able to nominate her successor; instead that privilege fell to Donald Trump. To avoid something like this happening again, political pressure grew on the 83-year-old Breyer to retire while the Democrats hold the presidency and fifty seats in the Senate, whose members confirm the appointment of presidential nominees to the court.

The US Supreme Court has assumed one hell of a power, one hell of a presence. And not just by striking down laws it finds unconstitutional – legitimately or by whim. Events in America’s recent history have magnified the court’s profile; its partisan contortions in favor of George W. Bush in the case of Bush v. Gore decided the 2000 presidential election.

But nothing has done more to push the court into the public eye than abortion. Which is strange, in retrospect, given abortion was not a partisan issue. The opinion in Roe was written by Harry Blackmun, a Nixon appointee, and supported by four other justices appointed by Republican presidents. In dissent were Rehnquist, another Nixon appointee, and Byron White, a socially conservative Democrat, who had been nominated to the court by John F. Kennedy. Over time, however, the growing influence of evangelical moralism in Republican politics meant that opposition to Roe emerged as a litmus test of party loyalty, and the composition of the court became a matter of heated public interest.

For a long time, the Senate – once a patrician club whose members looked down on the vulgar partisanship found in the House of Representatives – steered clear of demagoguery and militancy. The uncompromisingly anti-abortion Scalia, an adherent of Catholic natural law doctrines and the father of nine children, was confirmed with a 98-0 vote by the Senate in 1986; and in 1993 his ultra-liberal counterpart Ruth Bader Ginsburg – a champion of women’s right to choose, though not of Blackmun’s reasoning in Roe – received a similarly overwhelming endorsement, 96-3.

But between these smooth confirmations two brutal confirmation battles – for Robert Bork, rejected by the Senate in 1987, and for Clarence Thomas, narrowly confirmed in 1991 – presaged the hyper-polarization of the present-day confirmation process.

Bork and Thomas, like Scalia, espoused originalism, a reactionary trend in American jurisprudence whose followers try to recover either the original intent of the framers of the late 18th-century constitution or the meaning the document would have had for the generation that ratified it.

In her recent history of the Court, Jackie Calmes notes:

This leaves no scope for the notion of a “living constitution” which evolves in response to the changing practices and beliefs of American society. An adherent of the living constitution might conclude, for example, that the “cruel and unusual punishment” prohibited by the Eighth Amendment wasn’t a historically fixed standard but depended on shifting notions of morality and common decency. Originalists don’t see things this way; and the emergence of this palaeoconservative fad in the 1980s generated huge anxiety that its proponents wanted to replace late 20th-century freedoms with 18th-century restrictions.

Ted Kennedy set the tone in a set-piece speech in the Senate, repudiating Reagan’s nomination of Bork: “Robert Bork’s America is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, Blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens’ doors in midnight raids”. Bork made matters worse. A former Yale law professor, he treated his Senate hearings as a seminar on originalism, which served only to rile the senators, irritated by his condescension. The Senate decisively rejected him by 58 votes to 42.

Thomas’s nomination – an atypically conservative Black judge replacing a very liberal Black justice, Thurgood Marshall – also provoked considerable outrage, but it fell short of the vituperation directed against Bork. Liberal opposition to Thomas was tinged with embarrassment: blocking the elevation of only the second Black justice to the court was not a good look. Further discomfort was to come during the Senate hearings, when a former colleague, Anita Hill, accused Thomas of sexually suggestive comments and advances. Thomas – who scraped in on a 52-48 vote – described the media firestorm as “a high-tech lynching for uppity Blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves”.

The televised hearings on the Bork and Thomas nominations left scars, on both parties. Republicans regarded Bork as a martyr and Thomas as the victim of muckraking. Democrats felt that the Senate Judiciary Committee had not treated Anita Hill with respect; that a vote had been taken on Thomas before a proper investigation of her allegations had been conducted; and that, as a result, a known sexual harasser had gained a lifetime appointment to the court. The Thomas hearings were also an albatross for Biden, then chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, who had conspicuously failed to rein in the white, male Republican senators intent on demolishing Hill’s story.

But after Bork, the lesson was learned: Supreme Court nominees should stick to small talk with the Senate, and steer clear of controversial areas of jurisprudence. Say nothing substantive when asked. And the White House saw that to avoid a repeat of the controversy that nearly sank Thomas, it was vital to do proper background checks on potential nominees.

Well, kind of.

But was due diligence limited to adult misdemeanours? Until Trump’s nomination of Brett Kavanaugh in the summer of 2018, a candidate’s high-school years belonged safely beyond the horizon of senatorial scrutiny. Inevitably, Jackie Calmes in her book noted above, devotes considerable space to the trauma experienced by Christine Blasey Ford as a teenager, assaulted on a bed, she claims, at the hands of a drunken Kavanaugh and his friend Mark Judge.

However, the human drama of Ford’s story, her treatment by the Senate Judiciary Committee and Kavanaugh’s bizarre counter-testimony are set inside a bigger picture: the concerted attempt over several decades by the Federalist Society, an organization of right-wing lawyers and law professors, to reshape the judiciary as a reliably conservative force in the culture wars. Democrats had labelled Kavanaugh – a member of the Federalist Society since 1988 – the “Forrest Gump” of American conservatism, always in the vicinity at moments of high drama: assisting the independent prosecutor Ken Starr’s obsessive pursuit of the Clintons in Whitewater and Monicagate, and flying down to Florida as part of Bush’s legal team during the disputed election of 2000.

But in late September 2018 his career appeared to stall. Ford’s testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee was riveting and highly credible. At best, it seemed possible that both Ford’s allegations and Kavanaugh’s denials were grounded in truth, that Kavanaugh had been so drunk he had completely forgotten the incident.

In the wake of Ford’s impressive testimony, Kavanaugh was told that he needed to perform during the televised hearings for an audience of one in the Oval Office.

But instead of the punchy aggression Trump admires in a man, Kavanaugh displayed his inner teenager – whiny, entitled and snarky to grown-ups. It disgusted many. A nominee was auditioning for a job on the highest court, one for which core criteria are judicial temperance and nonpartisanship, and displaying the opposite traits. The hearing was punctuated with his cry-baby outbursts, “smart-alecky” responses and in-your-face contempt for Democrat senators.

The Senate delayed its vote for a week while the FBI went through the motions of investigating Ford’s claims (as was subsequently disclosed, the FBI never did any investigation).

But its bosses in the Republican administration had no interest in uncovering the truth. The FBI was also reluctant to assess the allegations of Deborah Ramirez, a Yale contemporary, who said that a drunken Kavanaugh had waved his penis in her face at a party.

Regardless of the sexual harassment claims, Calmes notes that many of Kavanaugh’s contemporaries believed he had lied under oath about the scale of his drinking as a young man. In the event, 49 Republicans and the conservative West Virginia Democrat Joe Manchin saw Kavanaugh through the Senate on a 50-48 vote.

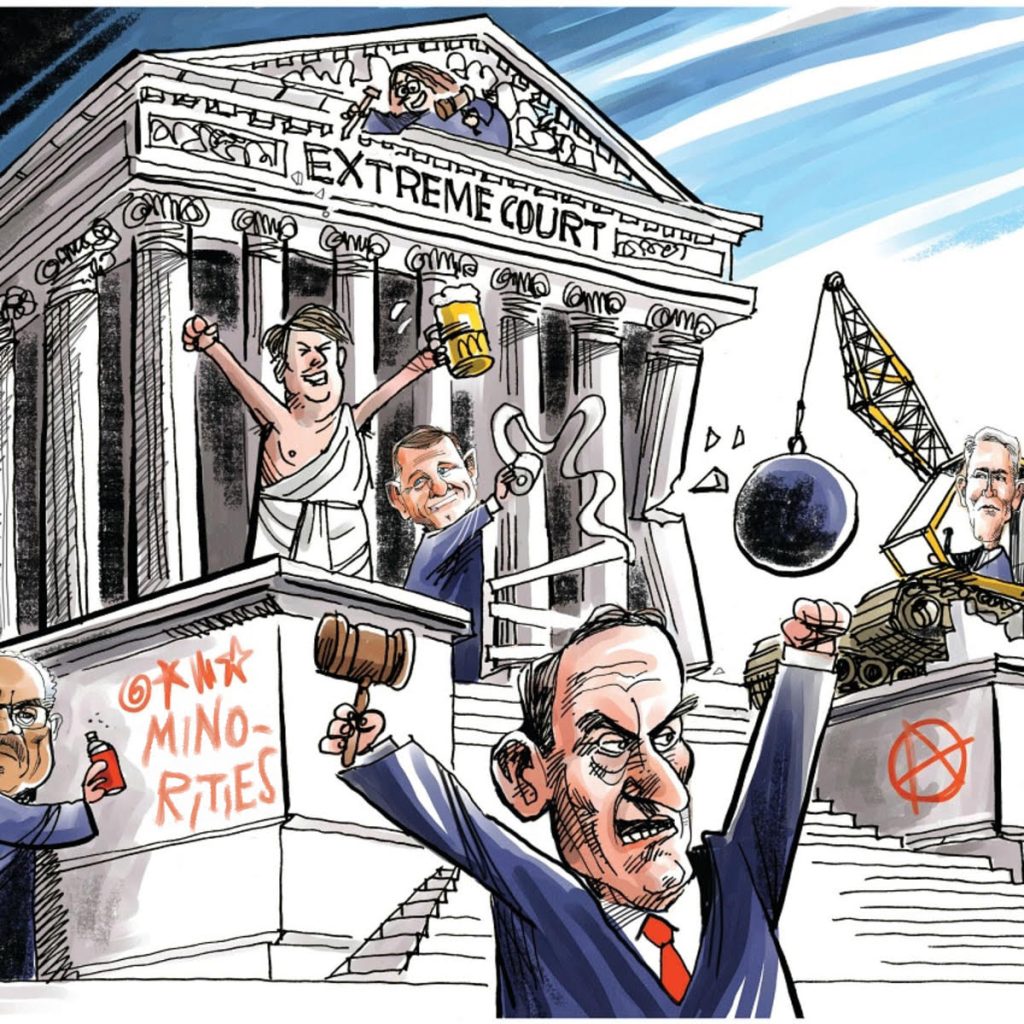

Although himself a staunch Republican and social conservative, Chief Justice John Roberts faced a dilemma. Not only was his Supreme Court, with its new conservative majority, markedly out of step with a country where Republicans had won the popular vote only once in the previous five presidential elections, it also included two justices who, facing credible sexual harassment allegations during the confirmation process, had – it seemed to many – perjured their way onto the court.

Its legitimacy was now in question, and with it the idea that the rule of law could be distinguished from partisan preferences. The Court would never recover.

Roberts tried to estrange himself from the court’s hard right. But in the year that saw the death of the liberal feminist Ginsburg and her replacement by Amy Coney Barrett, an ultra-conservative Catholic and mother of seven (two adopted), who belongs to a fringe charismatic renewal movement called People of Praise, it all scared the crap out of Roberts and he saw he might lose his power. And he got tired of hearing “it’s the Alito Court, not the Roberts Court” so he began to tow the line.

A far from uncontroversial choice, Barrett was confirmed only eight days before the 2020 presidential election, in which ten million people had already cast their ballots. Memories of the Republican shenanigans in 2016 were still fresh in the mind. When Scalia died suddenly in February that year, McConnell solemnly pronounced that the Senate could not allow Barack Obama to make an appointment to the court during an election year, though the election was then nine months away. He successfully blocked hearings for Merrick Garland, Obama’s nominee. Four years later McConnell – who has stated that the Senate’s constitutional function of providing ‘advice and consent’ in judicial appointments ‘means whatever the majority at any given moment thinks it means’ – rushed through Barrett’s confirmation in the weeks before the election. The living constitution is thriving – if only in the wiles of its most formidable political opponents.

Thanks to McConnell, by the end of his tenure Trump had appointed three comparatively young right-wing justices to the court: Neil Gorsuch (who eventually replaced Garland as the nominee), Kavanaugh and Barrett, of whom Kavanaugh at 59 is the oldest. Given that John Paul Stevens recently served on the court until the age of ninety (he retired in 2010), there is every possibility that future generations will find themselves subject to the rulings of Trump’s judicial picks. The court now has a heavy, almost unbreakable 6-3 conservative majority.

Roberts has finally given up. He has given up his notion that bolstering the shaky legitimacy of the court itself for the longer haul is most important. Nope. Ramming through a conservative judicial program is the most important thing.

And this term today’s Trump impunity opinion was merely icing on the cake. The most powerful, most disruptive opinion was Loper Bright Enterprise v Secretary of Commerce which sharply curbs the power of federal agencies. Conservatives and corporate lobbyists have already begun plotting how to harness the favorable ruling in a redoubled quest to whittle down climate, finance, health, labor and technology regulations in Washington.

The early strategizing has underscored the magnitude of the justices’ landmark decision, which rattled the nation’s capital and now appears poised to touch off years of lawsuits that could redefine the U.S. government’s role in modern American life. The opinion invalidated a decades-old legal precedent that federal judges should defer to regulatory agencies in cases where the law is ambiguous or Congress fails to specify its intentions. This means that agencies are going to have a hard time defending their legal positions.

To the barricades!!