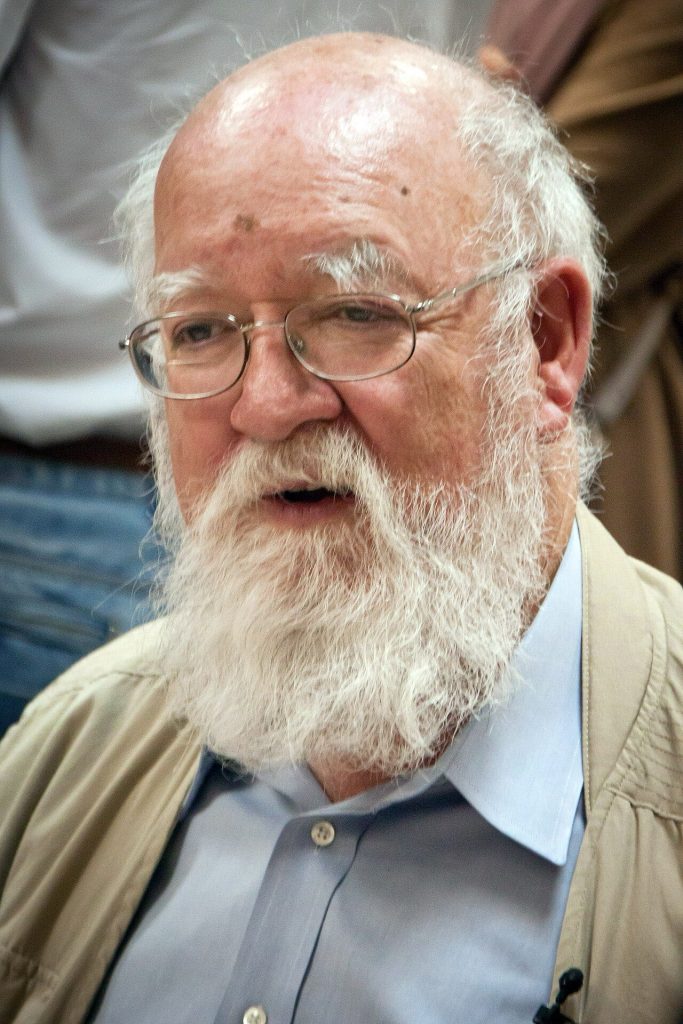

21 April 2024 – The world has sadly just lost one of its most provocative and inspirational thinkers and writers, Daniel Dennett. As Doug Hofstadter notes below, Dennett was a deep thinker about what it is to be human. I totally agreed with Dennett’s conclusions about consciousness – essentially that it is just an emergent effect of physical interactions of tiny inanimate components (explained more fully below).

I want to share a beautiful tribute that Doug Hofstadter wrote this week to friends and relatives, but that he decided to make a public document.

Dear friends and relatives,

I just received the very sad news about the passing of Dan Dennett, a lodestar in my life and in many thoughtful people’s lives.

Dan was a deep thinker about what it is to be human. Quite early on, he arrived at what many would see as shocking conclusions about consciousness (essentially that it is just an emergent effect of physical interactions of tiny inanimate components), and from then on, he was a dead-set opponent of dualism (the idea that there is an ethereal nonphysical elixir called “consciousness”, over and above the physical events taking place in the enormously complex substrate of a human or animal brain, and perhaps that of a silicon network as well). Dan thus totally rejected the notion of “qualia” (pure sensations of such things as colors, tastes, and so forth), and his arguments against the mystique of qualia were subtle but very cogent.

Dan had many adversaries in the world of philosophers, but also quite a few who shared his views, and as for myself, I was almost always aligned with him. Our only notable divergence was on the question of free will, which Dan maintained exists, in some sense of “free”, whereas I just agreed that “will” exists, but maintained that there is no freedom in it. (Scott Kim joked that I believed in “free won’t”, which was very clever, but really the negation should apply to “free” rather than to “will”.)

Dan was also a diligent and lifelong “student” (in the sense of “studier”) of evolution, religion, artificial intelligence, computers in general, and even science in general. He wrote extremely important and influential books on all these topics, and his insights will endure as long as we humans endure. I’m thinking of his books Brainstorms; The Intentional Stance; Elbow Room; Consciousness Explained; Darwin’s Dangerous Idea; Kinds of Minds; Inside Jokes; Breaking the Spell; From Bacteria to Bach and Back; and of course his last book, I’ve Been Thinking, which was (and is) a very colorful self-portrait, a lovely autobiography vividly telling so many stories of his intercontinental life. I’m so happy that Dan not only completed it but was able to savor its warm reception all around the world.

Among other things, that book tells about Dan’s extremely rich life not just as a thinker but also as a doer. Dan was a true bon vivant, and he developed many amazing skills, such as that of house-builder, folk-dancer and folk-dance caller, jazz pianist, cider-maker, sailor and racer of yachts (not the big ones owned by Russian oligarchs, but beautifully crafted sailboats), joke-teller par excellence, enthusiast for and expert in word games, savorer of many cuisines and wines, wood-carver and sculptor, speaker of French and some German and Italian as well, and ardent and eloquent supporter of thinkers whom he admired and felt were not treated with sufficient respect by the academic world.

Dan was also a most devoted husband to his wife Susan — they were married for nigh-on sixty years — and a great dad to their two children, Peter and Andrea. He entertained the kids by building all sorts of things for them, and he supported them through thick and thin. I saw that from up close, and really admired his ardent family spirit.

Both Dan and Susan had near misses with death over the past decade or two, and on one of those occasions — his own close call when his aorta ruptured — he wrote a memorable essay called (if I recall correctly) “Thank Goodness”, which was all about how the human inventors and practitioners of modern medicine had saved his life (and the lives of countless others), and that it was deeply wrong to “thank God” for saving anyone’s life, and that what should be thanked was human goodness incarnated in the form of all those people who so deeply cared about helping their fellow humans (nurses, doctors, medical researchers, etc.). Although Dan understood why his religious friends prayed for him, he thought that such actions were profoundly misguided and that belief in divine intervention was not a healthy approach to life.

Like his friends Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris, and Richard Dawkins (the quartet was nicknamed “the four horsemen of the apocalypse”), Dan was a committed atheist — and unlike me, he didn’t shy away from applying that word to himself, with all its flavors of an aggressive anti-religion stance — and he tried to explain, with great patience and subtlety, what is so compelling about religion to the human mind, but what is at the same time, so wrong about it.

Probably Dan’s two greatest heroes were Charles Darwin and the philosopher Gilbert Ryle (who was his doctoral advisor at Oxford), although he had quite a few others (including, for example, Cole Porter and J. S. Bach). Dan had many friends of many sorts in many lands all around the world, and I was proud to be one of them. He and Susan loved hosting their friends at their farm in Maine, which they owned and operated for about 40 years, and Dan himself did much of (probably most of) the physical maintenance of the home and the fields and trees, learning a great deal from his Maine neighbors. Dan loved Maine and he loved calling it “Down East” (as the Maine folks do), and he loved the jargon he picked up from farming and from sailing, and he employed it often in his writings (and I was often a bit thrown by some of the terms he dropped with such ease and naturalness, as if everybody were as familiar with farm life and the sailing life as he was). I once offhandedly called Dan a “tillosopher”, and he loved the epithet and even embraced it with delight in his recent autobiography.

Dan was a bon vivant, a very zesty fellow, who loved travel and hobnobbing with brilliance wherever he could find it. In his later years, as he grew a little teetery, he proudly carried a wooden cane with him all around the world, and into it he chiseled words and images that represented the many places he visited and gave lectures at.

Dan was a truly faithful friend to me over the four-plus decades that we knew each other. He always supported my ideas, and I am proud that he often sought feeback from me on drafts of manuscripts that he was writing, and I often provided detailed suggestions. Seldom did I disagree with the thrust of his ideas; I usually just provided suggestions for how to phrase a sentence a tad bit more clearly, or perhaps some examples that would support his point. I’m proud that over the years, I moved him close to my position on the importance of using nonsexist language in one’s speech and writing.

Some of Dan’s insightful essays, such as “Real Patterns”, which talked about what “exists” in the abstract two-dimensional world of John Conway’s amazing Game of Life (and by analogy, about what “exists” in our 3-D physical world), were deep mind-openers, as was of course his brilliant short story “Where Am I?” (one chapter in Brainstorms), which led to our friendship and our intimate collaboration on the anthology The Mind’s I, way back in 1980 and 1981.

Dan appreciated me in ways that I will never forget, and he counseled me wisely and empathetically concerning romantic dilemmas during the year I was on sabbatical in the Boston area. He was deeply considerate and compassionate, and as I say, filled to the brim with zest and enthusiasm. He was a great dad and a great husband and a great friend, as well as a great intellectual and a great writer. He was “bigger than life”, as my friend David Policansky described him, one time when we together were guests at Susan and Dan’s farm in the early 1980s.

I personally will deeply miss Dan, and so will so many other thoughtful people — even people with whom Dan seriously disagreed, such as my old doctoral student Dave Chalmers, whose ideas on consciousness are diametrically opposed to Dan’s, but their friendship was warm because they both valued honest human contact and respect, and clear communication, far above such goals as fame or power or status.

Dan Dennett was a mensch, and his ideas on so many subjects will leave a lasting impact on the world, and his human presence has had a profound impact on those of us who were lucky enough to know him well and to count him as a friend.

Requiescat in pace, Dan.

Yours,

Doug.