By historical standards, it’s a puny amount. And that tells you several things.

But it also points to the underlying disconnect between the West and the South and the non-aligned world over the war in Ukraine – “the West versus the Rest”. Poor countries are focused on food and fuel, not black‐listing Moscow over the Ukraine war.

3 JUNE 2023 — Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022 it has caused enormous damage. Thousands of people have died and billions of dollars’ worth of infrastructure has been destroyed in Ukraine. Yet all this damage has come at a relatively mild cost to Russia. As I noted in a previous post, its economy is holding up much better than almost anyone expected, partly due to spiking trade and the failure of sanctions. And the direct fiscal cost of the war – what it is spending on men and machines – is surprisingly low.

Russia’s budget is murky – especially its military one. So estimates of what Russia is spending on invading Ukraine is imprecise. But the legendary Rand Corporation – with its gazillions of sources that allows it to provide the most riveting analysis of almost any topic – have come up with a figure. In essence this involved, in part, taking the Russian government’s pre-invasion forecast of what it would spend on defence and security, and comparing that with what it is actually spending via Rand’s wealth of data points. That would put the cost of its invasion at 5trn roubles ($67bn) a year, or 3% of GDP.

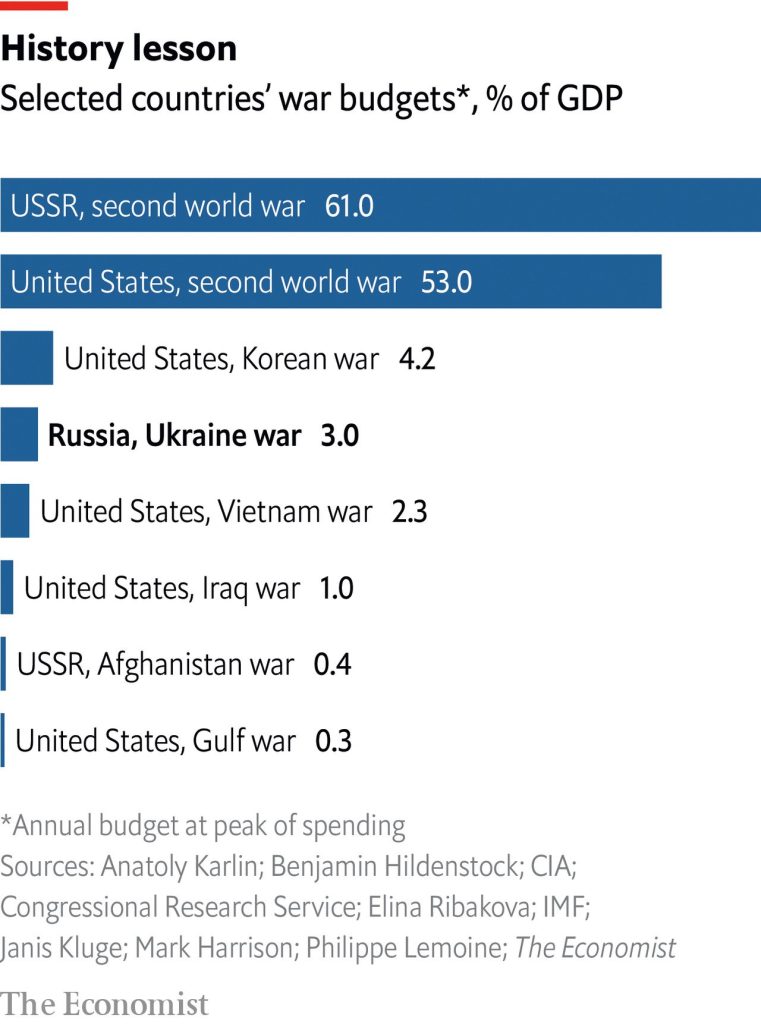

The Economist looked at all of the numbers and figured that by historical standards that was a puny amount. It’s data analytics team compiled estimates of spending on other wars – some involving Russia, some not – and produced this nifty chart:

At the peak of the second world war the USSR spent 61% of GDP on the war effort. Around the same time America spent about 50% of GDP on its military forces.

Going deeper, Rand offers 3 reasons explain why Russia is spending so little:

The first is political. Many within the Russian government would like to continue to portray the war on Ukraine as a “special military operation”. It would hardly make sense for such an operation to cost a double-digit percentage of GDP.

The second is economic. Russia would struggle to expand the war effort without costing its citizens dearly: printing money would spur inflation, eroding living standards; loading up banks with public debt might have a similar effect; tax rises or a big shift in public expenditure towards defence would also eat into personal incomes. This is a problem for Putin, who has presidential elections in 2024. Putin’s victory seems certain, but he does not want the potential embarrassment of large demonstrations, as happened for example in legislative elections in 2011. Already there are multiple stories of Russian citizens smearing dog shit on the cars of Russia officials and firebombing government buildings due to the human cost of the war for the average Russian family (some regions have lost 4% of their population due to conscription). Hence Putin’s speech a few days ago where he said “national defence is our top priority” but in resolving strategic security tasks in this area “we should not repeat the mistakes of the past and should not destroy our own economy”.

The third reason relates to defense economics more broadly, and this goes to a Rand/NATO briefing I attended a few weeks ago. Today’s armed forces are far more efficient than the ones of the past. They need ever fewer people and their machines are ever more accurate. The economic theory of “cost disease” suggests that high-productivity sectors tend to command a smaller share of GDP over time (unlike something like health care, which tends to take up a bigger share). Spending a lot less than you did in 1945 can still buy you a powerful army.

But it also points to the underlying disconnect between the West and the South and the non-aligned world over the war in Ukraine – “the West versus the Rest”.

It was supposed to be a moment of solidarity, the “free world” standing as one against brutality and aggression. Shortly after the start of Russia’s war in Ukraine, U.S. President Joe Biden said:

“The democracies of the world are revitalized with purpose and unity found in months that we’d once taken years to accomplish”.

The months since have in many ways vindicated such proclamations: the United States and its allies in East Asia and Europe have demonstrated remarkably deep resolve and minimal dissension in their support of Kyiv.

But elsewhere, it’s another story. The unity among Washington’s closest partners has made clear just how differently much of the rest of the world sees not only the war in Ukraine but also the broader global landscape. Governments and populations across much of the developing world have met gauzy “free world” rhetoric with a series of increasingly vehement objections: about Western double standards and hypocrisy, about decades of neglect of the issues most important to them, about the mounting costs of the war and of sharpening geopolitical tensions. The West, as a group, disregards the resentments and interests animating these countries. Unaddressed, they will become a source of even greater challenge and disorder in the years ahead, no matter what happens on the ground in Ukraine.

If it wasn’t so serious, it would be comical. Here’s what was meant to happen. After Russia fell upon Ukraine in February 2022, the international community – other than those the West has designated rogue and pariah states – would rally to condemn and resist the atrocity. The largest act of predation against a sovereign state in living memory was a great wrong that must be righted. Vladimir Putin’s attempted annexation was a security threat to all. It violated a precious, postwar global norm, the norm against conquest. This threatened the “Global South”, a condescending term of art for poor, postcolonial countries that lumps together everyone from Burundi, the poorest state on earth, to India, which has a space program.

The mantra was screamed: under the “global leadership” of the United States with its NATO and treaty allies in Asia, the peoples of South America, Africa, the Middle East and Oceania would come together to repudiate not only the invasion of Ukraine, but the old order of imperial aggression, sphere‐of‐influence prerogatives, genocidal expansionism and great power presumption. It was not just a collective effort to help Ukraine against an aggressor. It was a noble undertaking to rescue the world from the nineteenth century. For a time, it looked as though this might come true. As Russia recognised secessionist republics in Ukraine and mobilised on the border, Kenyan ambassador Martin Kimani made a celebrated speech at the United Nations Security Council. With moral clarity dialled up to “11”, he linked Putin’s despoilation of his neighbor with a past that should be left behind, warning against stirring the “embers of dead empires”.

Then, as Russia’s initial assault met unexpected resistance, Joe Biden, in his State of the Union address in March 2022 spoke of a world response. Putin “thought he could roll into Ukraine and the world would roll over. Instead, he met a wall of strength he never imagined.” Large majorities of the UN General Assembly condemned the invasion and called for Russia’s unconditional and immediate withdrawal. Russia, observers enthused, was ever more “isolated”. Was the moment of Western unity also one of international solidarity?

No, it was not. Outside the Western orbit, the US and its treaty allies, countries have not put their money where their mouths are. Indeed, they are frequently cautious with their mouths. Kenya, whose envoy denounced empire, has since hedged on the question. Its UN vote aside, it did not condemn the invasion. As Patrick Porter noted (a professor of international security at the University of Birmingham in the UK and a brilliant read on real great power politics and the consequences of the West’s decline):

President William Ruto of Kenya needs to purchase Russian oil to steady local fuel prices, and fertilisers to help farmers against drought, just as Malawi accepts Moscow’s fertiliser donation as the Russian flag fluttered alongside Kenya’s in Lilongwe. A similar pattern of accommodation holds in many other places, as Russia launches its own scramble for Africa with exports of grain too. Larger, richer nations also stand aloof from the exhortations of US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken. India abstains in UN votes and raises its crude oil imports from Russia significantly, as does China, which purchases raw materials and energy at a discount. NATO member Turkey has played both sides, dealing as it must also with inflation, an earthquake and dependence on Russian energy.

Those eager to play up Russia’s “isolation” point to votes at the UN, but this is weak tea. Talk, and gestures that promise no further commitment, are cheap. Such votes are largely ceremonial and low‐cost. Raising an arm to condemn an invasion without backing it up with hard coercion may look significant. But judge states, rather, by what they materially do. For “global norms” to be real, they must be non‐expendable, going beyond in‐principle abstractions. Countries must be willing to bleed for them. To be meaningful and effective, isolating Russia would not stop where a nation’s trade and arms begin.

Let us face the brutal facts. Russia is not “isolated”. Global norms are disposable. Most of the world does not crave any one state’s “leadership”. This past year has featured one large non‐event, the worldwide rallying that wasn’t. So why are these countries hedging? And why can’t some informed observers in the West see this simple truth?

One answer on offer is a cultural‐historical one, one noted in the current issue of Foreign Affairs magazine by Matias Spektor, a Professor of International Relations and founder of the School of International Relations at FGV in São Paulo, Brazil, who examines climate change politics, political violence, and international security in the Global South:

Countries are hedging out of anti‐Western sentiments, such as grievances over European imperial legacies. East Africa journalist Khatondi Soita Wepukhulu has detailed the West’s oppressive behaviour in the past and present accounted for African countries’ reluctance to join the coalition behind the “good fight”. Similarly, you can see South Africa’s hedging flows from its historical non‐alignment and fidelity to Russia’s friendship with the anti‐apartheid movement. This general refusal to harken is a “protest” vote against Western misbehaviour, from vaccine hoarding to under‐funding of climate mitigation measures. It flows from a general suspicion that Western moral talk is part of the old game of the strong pressuring and patronising the weak.

But who is being patronising, exactly? You can easily argue that these explanations, benign and well‐intended, are also naïve and Western‐centric. In a kind of reverse narcissism, they make the issue almost exclusively about “us” and our historical failures and crimes. The world in these litanies is little more than a morality play about Western error and redemption. Power politics in the “Global South” is missing in action. Those countries, in this account, exist and think almost entirely in the past.

That approach is profoundly mistaken. While the past haunts everyone, those in charge of countries that aren’t Western client states must live aggressively in the present. These regimes care more about their own survival, and/or their peoples’ hunger and basic needs, than sacrificing for international principles. Against the grain of so much discussion, they do not act primarily as former colonial subjects. They are not enslaved to a resentful memory of empire or displeasure at the more recent hypocrisies of Washington or London. They act as ruthless nation‐states, with all the traditional double standards and slipperiness that entails. If this patronising Western conceit were true, if such countries were primarily driven by historical allegiances and grievances, and not the reality of their situations, they would hardly pick and choose their commitments so adroitly. Yet in fact they willingly accept or seek out Western patronage as it suits. They buy Western weapons, accept Western development aid or undertake military exercises with NATO or the United States as it suits them. The West’s image in their eyes shifts between historical oppressor and contemporary partner as circumstances shift.

Or take Saudi Arabia, never shy of bringing up – and then overlooking – the suffering in Gaza or the West Bank, explaining the geography of the Gulf’s conciliatory stance with Russia as stressing not global norms but “regional security”. As for Beijing, its historical memory and propagandist centrepiece, the “Century of Humiliation”, that it suffered at the hands of European empires does not prevent it aligning increasingly with Russia even as Moscow speaks in nakedly imperial terms about Ukraine.

This is a complex issue and really beyond the scope of this post. This à la carte behavior is really all part of a larger pattern of energy diplomacy, whereby determined states pursue both resources and leverage, making sure their diplomatic stances are valuable bargaining chips. It needs a far fuller examination than I am giving it here.

I’ll finish with this. To expect a great global rallying against evil in which countries outside the Euro‐Atlantic orbit join in and isolate Russia, is to try to sing a world into existence that simply does not exist, rather than observe the world as it is. As this episode has demonstrated, we do not live in a world that revolves around cosmopolitan solidarity or global norms. We live in a world of ultimate solitude. Countries tend to put the pursuit of harder interests closer to home first, and other things second. Those that don’t suffer penalties. It is because hunger and scarcity are real and motivate both us and our rulers. The first duty of any government is to look after its own citizens, a morally serious business, before committing to internationalist self‐sacrifice. Try going without food and electricity for three days. That is just the way the world works.

And so it makes complete sense that countries value preserving a relationship with Moscow as they try to keep the lights on and the energy and food supply alive, or as they fear potential aggressors nearby. That we need reminding of this point is an indictment not of humanity, but of the Western foreign policy commentariat. Far too many of us are blinkered by not knowing true hunger. We have never known it, grazing on baguettes and cappuccinos as we hop from symposium to work conference to airport. We . are . spoiled.

Too many of us thinks the world is a shrunken place, where there are few trade‐offs between pressing interests “over here” and more distant and less urgent ones “over there.” Too many of us spend too much time gathering to hymn ahistorical abstractions like the “rules‐based order” (it does not exist) and declaring their “transnational allegiances”. Boys and girls: spend some time studying more prosaic things like raw materials, industrial capacity and supply chains.