Russia may have placed too much faith in “force ratios” in its invasion of Ukraine

15 May 2022 – Most of my readers have been receiving my continuing series on the Ukraine War except for my more detailed posts on military stratagems which explain why the Ukrainian military has defied expectations which have only been of interest to my hardcore military and intelligence community readers. In the case of the Ukrainian armed forces, I’ve tried to explain how they’ve performed well beyond what was anticipated despite a profound imbalance in military capabilities, particularly in air and naval power and long-distance missiles. The secret to Ukraine’s success rests first of all on its mindset – one Russia itself has strengthened – backed up by dynamic military strategies that have exploited the weaknesses of a powerful, overconfident adversary.

But there is one element that might appeal to my broader readership. Early in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it wasn’t just Moscow that believed its offensive could succeed quickly. In February, even U.S. officials warned Kyiv could fall in days. Russians had numbers on their side, or more precisely a number: the 3:1 rule, the ratio by which attackers must outnumber defenders in order to prevail. It is one of several “force ratios” popular in military strategy, and heavily relied upon by Russian military strategists. Russia, it seemed, could amass that advantage.

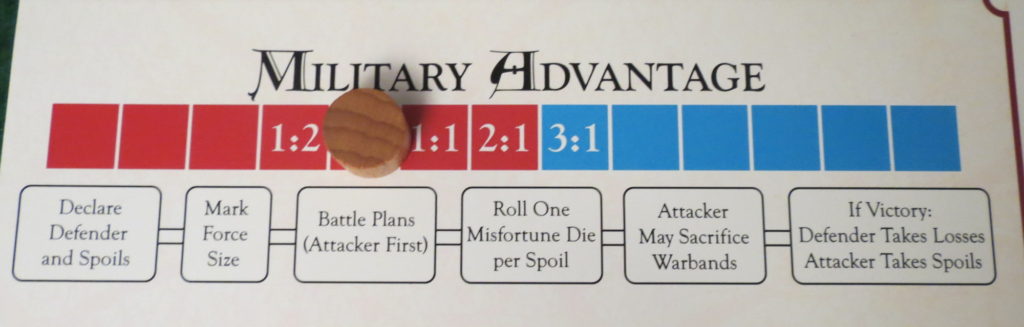

The war in Ukraine has brought renewed interest in force ratios. Other ratios in military doctrine include the numbers needed to defeat unprepared defenders, resist counterinsurgencies or counterattack flanks. Though they sound like rules of thumb for a board game like Risk, the ratios have been taught to generations of both American and Soviet and then Russian tacticians, and provide intuitive support for the idea Ukraine was extremely vulnerable. John Mearsheimer, a University of Chicago professor whose work focuses on security competition between great powers with an emphasis on data analysis, said at a recent RAND Corporation event analyzing the war to-date:

“It’s clear in this case that the Russians badly miscalculated. I would imagine that most of them were thinking in certain terms, that you need something on the order of a 3:1 advantage to break through”.

According to “force ratio” rules of thumb, these are the number of attacking troops necessary to succeed at certain missions:

Attacker : Defender ratio

Attack prepared/fortified defender 3:1

Attack a hasty defender 2.5:1

Counterattack a flank 1:1

Delay an enemy 1:6

Hold territory 20–25:1,000*

*members of the population

A look at the balance of forces between Russia and Ukraine at the start of the war

Active troops:

Russia – 900,000

Ukraine – 196,600

Ratio: 4.6:1

Reserve troops:

Russia – 2,000,000

Ukraine – 900,000

Ratio: 2.2:1

Main battle tanks:

Russia – 2,927

Ukraine – 858

Ratio: 3.4:1

Armored reconnaissance vehicles:

Russia – 6,050

Ukraine – 622

Ratio: 9.7:1

Infantry fighting vehicles:

Russia – 5,180

Ukraine – 1,212

Ratio: 4.3:1

Artillery:

Russia – 4,984

Ukraine – 1,818

Ratio: 2.7:1

Sources for the above information: U.S. Army Field Manual 6-0: Commander and Staff Organization and Operations (force ratios); International Institute for Strategic Studies (Russia/Ukraine forces); Central Intelligence Agency

Modern versions of the 3:1 rule apply to local sectors of combat. A detailed Rand Corporation study determined a theater-wide 1.5-to-1 advantage would allow attackers to achieve 3:1 ratios in certain sectors. Using that analysis plus a study by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (one of the major military think tanks, this one based in London) the determination was made that, overall, Russia’s military had quadruple the personnel and infantry vehicles, triple the artillery and tanks, and nearly 10 times the armored personnel carriers.

With 190,000 Russian troops concentrated to invade in February, and Ukraine’s military spread across the country, (only 30,000 troops, for example, were estimated to be in Ukraine’s east near the Donbas region) it appeared Russia had the numbers to overwhelm Ukraine.

But as the Rand Corporation noted in its presentation, plus as noted in the work of Stephen Biddle (a Columbia University professor who served on strategic assessment teams for U.S. generals David Petraeus and Stanley McChrystal in Iraq and Afghanistan) who has provided a steam of comment on Linkedin and Twitter, Russia’s struggles underscore how real wars are far, far more complex. As Biddle noted in a number of Tweets (and the following is a mash-up from his numerous Tweets):

“The empirical evidence for it is extremely weak. It’s not some law of science. It corresponds to some degree of intuition, but it’s a lousy social-science theory.

Ratios don’t account for 5 critical factors in this Ukraine War:

1. The extensive Western intelligence provided to Ukraine, and almost immediate materiel support to Ukraine

2. Ukrainian resolve

3. low Russian morale

4. Russia’s logistical struggles for which there seems to have been no pre-planning

5. severe Russian tactical errors, like leaving tanks exposed in columns on major roadways, easily attacked

In planning real combat operations, the U.S. military uses far more detailed analyses than ratios and rules of thumb”.

These force ratios originate from 19th-century European land wars

In his seminal 1832 text on military strategy, “On War”, the Prussian General Carl von Clausewitz proclaimed:

“The defensive form of warfare is intrinsically stronger than the offensive.”

By the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Prussians distilled this to requiring triple the attackers. Prussia decisively triumphed; maybe they were on to something.

World War I, with years of stalemate in the trenches as combatants struggled to break through defenses, lent further credibility to the idea. English Brigadier-General James Edmonds, writing shortly after World War I, recorded an early version of the rule:

“It used to be reckoned in Germany that to turn out of a position an ebenbürtigen foe – that is, a foe equal in all respects, courage, training, morale and equipment – required threefold numbers.”

After World War II, Colonel A.A. Sidorenko promoted the ratio in Soviet military doctrine. It is still in Russian military doctrine manuals obtained by Western intelligence services. The U.S. incorporated ratios in the 1955 update to the Army Field Manual – America’s military doctrine – that umpires used to referee war-game outcomes.

But there were skeptics and U.S. military strategy changed. According to a monograph on the ratios’ history by Army Major Joshua T. Christian, General of the Army Omar Bradley was one critic, worrying that tacticians were constraining their strategies in deference to overly simplistic rules of thumb. The ratios remain in the U.S. Army Field Manual today but with 100s of provisos.

In the 1980s, the ratios were central to a fierce debate over whether the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact, with superior numbers to NATO in Europe, could sweep to victory in conventional war. On one side, Mearsheimer (the strategist quoted above) argued Soviet-aligned forces would struggle to reach the 3:1 ratio where it counted, and thus could not swiftly crush NATO. He argued then and now that the rule applies narrowly to forces engaged in immediate breakthrough battles. Today, if Russia can amass enough force in one location, he worries, it could punch through the Ukrainian line. Once punctured, the tide can turn rapidly – such as, he said, when Nazis invaded France via the lightly defended Ardennes Forest.

Other scholars, like Joshua Epstein, promoted dynamic mathematical models to assess the military balance. Then a Brookings Institution fellow, he argued ratios were useless, citing examples where defenders or attackers prevailed far outside the ratio.

NOTE: at the top of this post I noted the game of “Risk”. In that game the math actually is clear: attackers win most large battles if they have 86% of the defending force, plus two. Just 88 attackers will usually beat 100 defenders; that makes a mockery of the 3:1 rule.

But before consensus was reached, the Cold War ended. For a happy generation, major European land wars seemed unimaginable. Epstein turned his mathematical modeling to diseases; he is now an epidemiologist at New York University. His work has been widely followed during the COVID epidemic. Still, he said of Ukraine:

“It’s obvious in this case, the force ratio, the number of static units, are a very poor predictor of what’s going to happen on the battlefield. Force ratios exemplify a quip from the writer H.L. Mencken – and a lesson Russia is learning the hard way: there is always a well-known solution to every human problem – neat, plausible and wrong”.