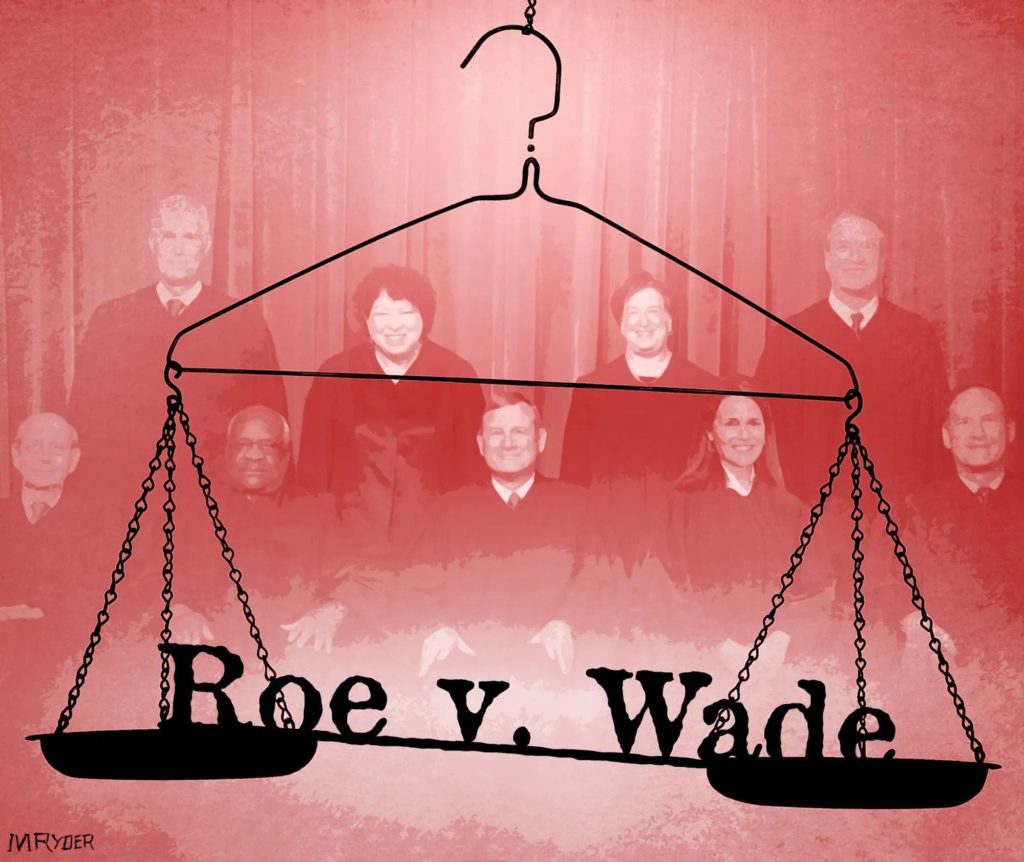

3 May 2022 – In 2003, when the Supreme Court held, in “Lawrence v. Texas”, that criminalizing gay sex was unconstitutional, it insisted that the decision had nothing to do with marriage equality. In a scathing dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote, “Do not believe it”.

Then, in 2013, when the Court struck down the federal Defense of Marriage Act’s definition of marriage as being between a man and a woman, emphasizing the tradition of letting the states define marriage, Scalia issued another warning, saying that “no one should be fooled” into thinking that the Court would leave states free to exclude gay couples from that definition. He was finally proved right two years later, when the reasoning on dignity and equality developed in those earlier rulings led to the Court’s holding that the Constitution requires all states to recognize same-sex marriage.

Last week Jeannie Suk (a professor of constitutional law at Harvard Law School and former clerk for Justice David Souter of the U.S. Supreme Court) noted on her blog:

Just as rights can unfold and expand, however, they can also retract and constrict in breathtaking ways, pursuing a particular strain of logic one case at a time. In the forthcoming decision in “Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization”, the Court is widely expected to overturn or severely undermine its abortion-rights cases, “Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey”. In fact, following the comments of the six conservative Justices at the oral arguments in December, the strength of this expectation has spurred state legislative efforts to proceed as if ‘Roe’ were already gone. A handful of states have passed laws, like the Mississippi law at issue in ‘Dobbs’, that ban abortion after fifteen weeks of pregnancy, in violation of precedents establishing that abortion cannot be banned before “viability,” at around twenty-four weeks. (On Thursday, Florida became the most recent.) Some of the laws have been blocked by the courts, but, if Mississippi prevails, the states expect to be free to enforce these bans.

Last night, in a stunning breach of Supreme Court confidentiality and secrecy, Politico obtained and published what it calls a draft of a majority opinion written by Justice Samuel Alito that would strike down Roe v. Wade. The draft was circulated in early February, according to Politico. The final opinion has not been released and votes and language can change before opinions are formally released. The opinion in this case is not expected to be published until late June. Politico says it has authenticated the draft and last night on Twitter several former Supreme Court law clerks and constitutional experts agreed it was the real thing.

Who leaked it and why? Oh, take a trip through Twitter and you’ll find all sorts of reasons. Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell says it is yet “another escalation in the radical left’s ongoing campaign to bully and intimidate federal judges and substitute mob rule for the rule of law”. Many say it was a leak done conservatives to freeze the majority in place and head off in-roads Chief Justice Roberts was making to tone down the option. Etc., etc., etc.

It appears that five justices would be voting to overturn Roe. Chief Justice John Roberts did not want to completely overturn Roe v. Wade, meaning he would have dissented from part of Alito’s draft opinion, “informed sources” told several media outlets, likely joining the court’s three liberals. That would mean that the five conservative justices that would make up the majority overturning Roe are Alito and Justices Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

Among the more restrictive bills currently under consideration across the country, more than a dozen emulate the Texas “heartbeat” law, which bans abortion after six weeks of pregnancy and allows only private citizens, not state officials, to enforce the ban. That provision insulates the law from being challenged as unconstitutional in federal court. The Supreme Court repeatedly declined to block the Texas ban, but did leave open a possible avenue to challenge it. In March, the Texas Supreme Court closed that avenue.

Idaho became the first state to enact a Texas-inspired law. Idaho’s law bans abortion after about six weeks, and allows family members (including a rapist’s relatives) of the “preborn child” to sue a provider who performs an abortion. The law was passed last month, but Idaho’s Supreme Court has temporarily blocked it from taking effect. Missouri has introduced a bill that allows private citizens to sue an out-of-state abortion provider, or even someone who helps transport a person across state lines for an abortion. Wyoming has passed a law that bans most abortions, which will be triggered if the Supreme Court overturns Roe. The boldest effort thus far, though, has been in Oklahoma, a destination for Texans seeking abortions. Two weeks ago, Oklahoma’s legislature made it a felony punishable by ten years in prison to perform an abortion except to save a woman’s life in a medical emergency. The governor signed the bill last Tuesday; the law is set to go into effect in August.

Overturning Roe will be the culmination of a half-century-long legal campaign singularly focussed on that outcome. And there are signs that, far from being an end in itself, it would launch even more ambitious agendas. In the Dobbs litigation, Mississippi denied that doing away with Roe would cast doubt on other precedents, set between 1965 and 2015, on which Roe rested or which relied on Roe. This series of decisions held that states cannot ban contraceptives, criminalize gay sex, or refuse to recognize same-sex marriage. The state told the Court that those cases are not like Dobbs, because “none of them involve the purposeful termination of a human life.”

But all of them involve the question of whether states should be able to make laws that affect some of the most intimate aspects of people’s lives. In recent weeks, in anticipation of the Dobbs decision, various Republican senators have questioned Griswold v. Connecticut, which struck down a state ban on contraceptives; Obergefell v. Hodges, which required states to recognize same-sex marriage; and even Loving v. Virginia, which invalidated a state anti-miscegenation law. Overturning Roe would almost certainly fuel the broader fight to get fundamental moral issues out of the realm of federal constitutional rights and under the control of the states.

The Alito draft published last night seeks to justify itself on the ground that it allows states to resolve the issue of abortion for themselves, through democratic processes, rather than by having a resolution imposed on them. At that point, it will be tempting to echo Justice Scalia’s “Do not believe it” warning. Although the legal arguments against Roe have focussed on returning the issue to the states, for five decades the core moral belief against the ruling has been that abortion is the termination of a human life. Last week, a twenty-six-year-old Texas woman was arrested on murder charges, for “intentionally and knowingly causing the death of an individual by self-induced abortion.” The prosecutor dismissed the case, saying that the Texas law did not apply to it. But the incident suggested a possible post-Dobbs future, in which states pursue criminal charges against people who have abortions as well as against those who provide them.

If true and the Alito opinion becomes law, it will only be a matter of time before pro-life legal efforts turn toward getting the Supreme Court to recognize the constitutional rights of the fetus. These efforts would focus on the same part of the Constitution that was previously held to provide the right to abortion, the Fourteenth Amendment, which prohibits states from depriving “any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” Fetuses are currently not considered to be persons. But Mississippi’s brief repeatedly notes the human attributes of the fetus, in utero, and it may be a precursor to future constitutional arguments to the effect that fetal personhood prohibits abortion.

In the face of such a push, liberals may one day find themselves advocating for leaving the matter to the states, and perhaps even seeking novel methods – like the one Texas concocted – to circumvent federal-court review of state laws protecting abortion access.

But whether or not it would take another fifty years or more for a fetal right to unfold, or the right of same-sex marriage to be over turned, the pro-life legal movement has demonstrated its ability to fight the long fight. And its agenda is only beginning. And there is a long history here.

In 1987, a widely overlooked book (and the best book I have read about the subject), is “Abortion and the Constitution: Reversing Roe v. Wade Through the Courts”. This book laid out the primary legal strategy abortion opponents would pursue for decades. These fervent anti-abortion attorneys, brought together by Americans United for Life, the leading anti-abortion legal group, recognized that the reversal of Roe would take careful planning and a long-term strategy. There were several prongs.

First, hack away at Roe’s foundations by discrediting the origins of the constitutional right to privacy, and expand the recognized justifications for restrictions. In this way they would gradually develop a new theory of constitutional jurisprudence that could subsume Roe’s entire rationale.

Second, target restrictions to particular types of vulnerable women — indigent women or young women, for example — and once upheld, apply the limits to a wider group.

But the third was the most important: these challenges would need to be heard by federal courts packed with conservative judges who would be willing to upend the law. Ultimately, conservative Supreme Court Justices would be key to Roe’s demise. Arguing that “nothing can be a substitute for patient deliberation, exhaustive research, and a grand design,” this group of almost entirely male lawyers committed to working for the reversal of Roe until the job was done. Because they were combatting relentless tactics developed by well-funded and politically connected opponents, abortion rights advocates that kept busy on all fronts – suddenly overwhelmed by the swarm of anti-abortion laws that poured out of a hive of states dominated by conservative legislators and governors.

Enter: the Republican Party. The anti-abortion movement became even more politically powerful by forging an alliance with the Republican Party. Recognizing that the public believed protection of women’s health was more important than protecting fetal life, particularly early in pregnancy, abortion opponents began to claim that they were “pro-woman” and committed to women’s health. They created groups with officious names like the Center for Medical Progress or the Center for Bio-Ethical Reform and used them to disseminate specious medical information and unsupported assertions about the physical and mental health risks of abortion—that abortion causes breast cancer, damages future fertility, and increases women’s risk of suicide or depression.

Such alleged risks are completely unsupported by the scientific literature and have been rejected by mainstream medical organizations such as the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists and the American Psychological Association.

But … no matter. State legislators and many courts relied on these erroneous claims to support burdensome health restrictions such as mandatory waiting period laws, state-sponsored misinformation on the risks associated with abortion, and the implementation of excessive, unnecessary clinic regulations known as Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers, or TRAP laws.

In addition, anti-abortion lawyers would ask the courts to rely on legislative findings rather than medical judgments or the prevailing views of the medical community to determine whether the restrictions actually furthered this purported interest in protecting women’s health.

But the key focus was the legal strategy was focused on filling vacancies on the lower federal courts and the Supreme Court with judges who believed that Roe was wrongly decided and who were willing to forsake the traditional doctrine of precedent that would normally require them to give great deference to the decision. Beginning in the 1980s, with the political power of the Moral Majority and President Ronald Reagan as a strong and savvy ally, the anti-abortion movement launched its strategy. Its high-ranking supporters in the Senate confirmed a pipeline of ultra-conservative anti-abortion judges onto the lower courts nationwide, who were then short-listed for a Supreme Court nomination.

One by one, they added anti-abortion conservative judges from this group onto the Supreme Court, beginning with Justice Thomas and followed by Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett. With a 6–3 majority in place by 2020, they now have surpassed the magic number five necessary to overturn Roe. The appointment of Justice Barrett positioned them to do so even without demonstrating the respect for precedent and procedural restraint previously needed to bring along Chief Justice Roberts, who prefers chiseling away at Roe rather than an outright reversal. It is no longer “Robert’s Court”. He has been emasculated.

The anti-abortion movement became even more politically powerful by forging an alliance with the Republican Party outside the Beltway where Republican legislators held real power. They passed a host of abortion restrictions at a fast and furious rate throughout the 1980s and 90s and on into the new millennium.

Unfortunately, it took the Democrats almost a decade to publicly support abortion, as party leaders (mostly white men) were fearful of losing working-class Catholics who had long been a part of their base. The political battles waged in state legislatures were key to anti-abortion success. But the Democrats had lost too much time. In the four decades after Roe, the anti-abortion movement’s state-level strategy resulted in over one thousand abortion restrictions being passed into law.

But overturning abortion is merely the start. The pace of restrictive laws varied over the decades, but the redrawing of state legislative district lines following the 2010 census swept abortion opponents into power in state capitals nationwide. An avalanche of restrictive laws soon flowed from these states. Between 2011 and 2016, over 400 laws restricting abortion had been enacted and countless more introduced, which according to the Guttmacher Institute, gives that period the “dubious distinction” of accounting for more abortion restrictions than any other single five-year period since Roe. As a result, abortion access was whittled away state by state, clinic by clinic, and doctor by doctor, leaving significant hurdles that made abortion rights simply a shell for many.

The attacks combined to make abortion expensive, risky, and often unavailable. The more vulnerable and disempowered a woman was, the further out of her reach abortion was. Those seeking the reversal of Roe urged legislators to target restrictions on particular types of women, primarily poor women, women of color, and young women, who had less political power to defeat the measures legislatively. Once these restrictions were upheld in court, other states were quick to adopt broader versions. Laws that cruelly denied Medicaid funds for low-income women to pay for abortions later served as a rationale for banning all abortion funding in government health insurance programs.

The pro-life legal movement has demonstrated its ability to fight the long fight. And Roe is just the start. Take some time and read the Dobbs case. Its premise involves the question of whether states should be able to make laws that affect some of the most intimate aspects of people’s lives. In recent weeks, in anticipation of the Dobbs decision, various Republican senators have questioned “Griswold v. Connecticut”, which struck down a state ban on contraceptives; “Obergefell v. Hodges”, which required states to recognize same-sex marriage; and even “Loving v. Virginia”, which invalidated a state anti-miscegenation law. Overturning Roe would almost certainly fuel the broader fight to get fundamental moral issues out of the realm of federal constitutional rights and under the control of the states.

The pro-life legal movement has demonstrated its ability to fight the long fight. And its agenda is only beginning.

As I noted above, if the Alito opinion savaging Roe and Casey ends up being the Opinion of the Court, it will unravel many basic rights beyond abortion and will go further than returning the issue to the states: It will enable a GOP Congress to enact a nationwide ban on abortion and contraception. But the electoral consequences of the end of Roe v. Wade is one of the biggest unknowns in American politics in 2022. Too complicated.

But one can still see a steep, sloping path down from here. Not long from now, some white lady – upper-middle class, everything going basically right in her life – is going to die because common medical procedures for her ectopic pregnancy were denied through judicial fiat. Her husband is going to be shattered by this. He’s not going to be able to reconcile the divergence between the comfortable, normal life he had lived and the preventable hellscape he is left with. And he is going to have five specific people to blame. So he will decide he has nothing left, and he will buy a gun, and he will shoot a Justice. That won’t make the world any better. It will get so much worse at that point. Recriminations will follow. We’ll end up in a lopsided war of all against all. Let me be abundantly clear that I’m not saying this should happen. I’m saying we have been heading toward that point for a long time so what I proposed is not a statistical outlier.

Democracy is a system whereby the ruling class obtains the consent of the governed. That democracy in America had failed and it is not coming back. And when society breaks down, it will go poorly for people like most of us (well, those that live in America). The police and the military – the people with formal authority, access to weaponry, and significant training – are stacked with right-wing ideologues. Gun fanatics are, for the most part, right-wing extremists. Liberals bring witty retorts to a literal gun fight.

A precondition of public trust in political institutions is that we have political institutions that are deserving of public trust. In America, 5 unelected, unaccountable members of the Supreme Court (all chosen by a president and a party in the minority) have decided that they can take away fundamental rights and expect a docile public to do nothing more than grumble and adapt. But those of us that follow the law in the U.S. know this. And we’ve known this was coming for a while. The biggest warning flare was in September, when the Court used the shadow docket to let the Texas 6-week abortion ban stand – the shadow docket being used more and more. The law has been emasculated. And there is nothing to be done. Oh, yeah. Tweet about it.

This is how collapse happens: quietly, amidst distractions. It’s why the ruling class fundamentally assumes they need fear no public reprisal. Orwell warned in 1984 that we would live under the watchful eye of a controlling state. Resistance would be futile because of the sheer scale of surveillance. Huxley warned in Brave New World that we would be furnished with such wonderful distractions that we would not bother to resist. America in 2022 is a mix of their two warnings, but ultimately I find Huxley offers the far more compelling insights.

Politics and governance is boring and frustrating and hopeless and disappointing. Here in Europe we go through the same stages. But it is the method by which we construct a society where we can live together. And it is bloody grinding work to make the world better. In the West, we got fooled into thinking liberal democracy is easy. And America has just gone through a decade of stupidity.

It’s been clear for quite a while now that red America and blue America are becoming like two different countries claiming the same territory, with two different versions of the Constitution, economics, and American history. Yes, the Tower of Babel. But the story of Babel is not a story about tribalism; it’s a story about the fragmentation of everything. It’s about the shattering of all that had seemed solid, the scattering of people who had been a community. It’s a metaphor for what is happening not only between red and blue, but within the left and within the right, as well as within universities, companies, professional associations, museums, and even families.

Striking down Roe is an act of judicial extremism. It signals that the conservative court majority has decided that there are no meaningful checks on their power – that they no longer need to operate incrementally or worry about the appearance of legitimacy. My guess is that in the near-term they will be vindicated, and in the medium-term it will hasten a slide into a cycle of violent recriminations, chaos, and upheaval.

Or just stick to the current plan and just do nothing.