The Twitter social-media platform isn’t a public square. It’s a gladiatorial arena. But the current fight is over attention and reach, not free speech. Herein a few notes from a draft-work-in-progress (apologies for typos; I skipped my editor).

30 April 2022 – Taken in its purest sense, Elon Musk is the ultimate creator and he’s emboldened others to act as he does. He sees the world and his companies as platforms for what he cares about, including his brand. This is a tremendous shift from the typical role of a CEO, and one that I think is seriously underestimated, which consists of leading a company and being accountable to their shareholders. That’s how he has run Tesla, of course. In fact, he is in the process of selling about 10% of his stock in Tesla – just as it is starting to hit its stride – to pay for a side project: buying Twitter. That’s not traditional CEO behavior. Most CEOs strain to hide their selling. He’s flaunting it.

And the trend of CEOs answering first and foremost to their own personal ambitions and brands isn’t going to stop with Elon. Look at the behavior of other CEOs on Twitter and you realize they see the roles very differently than previous generations of corporate executives. They see their companies as platforms to push political and social agendas, not as purely capitalistic enterprises.

Every founder in tech these days looks up (at least somewhat) to Elon. We’ve only seen the beginning. His Twitter takeover (if completed and while I have been up-and-down on this I now think it will be completed) will have profound implications for shareholders, and employees and the people who try to hold them to account (press and regulators). Four years ago I wrote a long piece that basically concluded the best way to understand the future of business is by following people, not the companies themselves. Following Jeff Bezos, Tim Cook, Jack Dorsey, Elon Musk, Satya Nadella, etc., etc. bears this out.

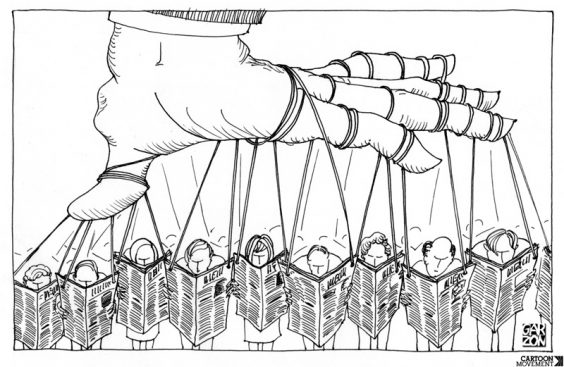

But, of course, if you’re going to be a “Creator CEO”, you need a platform as Casey Newton, Ben Thompson and many others have pointed out (and more on their musings shortly). Elon is close to getting one, Donald Trump wants one (Truth Social), Marc Andreessen has Clubhouse, etc. So get ready for the rise of the Twitter clones and other bespoke tech platforms owned and operated by figures that want to use them to bend the public discourse to their will. Man, Thiel’s attempt to shut down Gawker and Jeff Bezos’s purchase of the Washington Post will seem like child’s play compared to what I think will happen when the world’s richest people think they can own their own information superhighway. Now, I don’t think many of these efforts will succeed. But the attempts will be a big deal, distracting leaders from running their businesses and putting a further strain on their relationship with the Fourth Estate.

And so enter Musk, a new type of creator CEO, one poised to wrest power by owning a key communication channel, prompting a wave of response. But most of it really boiled down to this: haven’t powerful people long controlled the media, pushing it toward their own vested interests? Because the answer is obviously “Yes!” From the times of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer to the more recent era of Ted Turner and Rupert Murdoch, the biggest brands in media have long been owned by solo plutocrats. Yet those who dismiss Musk’s takeover of Twitter as just a modern example of a rich mogul buying printing presses or television stations are falling into a dangerous trap: they forget that the internet is unlike any communication technology that has come before it; they underestimate the power of the technology to scale and to control the public conversation. But make no mistake: Twitter is not “the public square”. It’s a gladiatorial arena (more on that a bit later in this post).

First, let’s talk about size. Tech’s reach is far bigger than that of any traditional media outlet. Just to take one example, Twitter has some 229 million active users. The most popular cable news network in the U.S., Fox News, is in about 90 million homes – yet recent media metrics show only a portion actually watch it.

And let’s not forget that tech platforms can scale exponentially through network effects while media companies can’t. The New York Times doesn’t get more valuable to its readers as more people read it. Twitter – along with Facebook, TikTok and others – do, because the additional users create more content. That’s the power of network effects which I have written about (ad nauseam) in numerous posts over the last 10 years. Twitter’s addressable market is far bigger than the audience of any one media company.

Plus, Twitter makes an impact in real time. Media companies certainly shape the course of history with their coverage and opinion – but not moment by moment. News networks have become reactive to the constant flood of ideas and pronouncements made on social media, not the other way around. And Musk knows from running Tesla, stocks can rise and fall on the content of his tweets. Politicians can and do negotiate via social media. (Remember when we thought Trump was going to start a nuclear war with Iran over a tweet?) And thus the person setting the rules of engagement on social media can have near-instantaneous power over no shortage of things.

Why do you think there is so much debate about an edit button on Twitter? Because the stakes are so high. As I noted in a previous post:

• Tweets that are part of a conversation are shown in chronological order, and, even though much of a tweet’s engagement is frontloaded, the Twitter archive provides instant and complete access to every public Tweet. This positions Twitter as a historical chronicler of record and a de facto fact checker.

• There are numerous ways to retrieve deleted tweets, which allows researchers to study them. While some studies show significant personality differences between users who delete their tweets and those who don’t, these findings suggest that deleting tweets is a way for people to manage their online identities. Analyzing deleting behavior can also yield valuable clues about online credibility and disinformation. Similarly, if Twitter adds an edit button, analyzing the patterns of editing behavior could provide insights into Twitter users’ motivations and how they present themselves.

• But it will make the job more difficult. Given partisanship and political polarization in online spaces, allowing users – whether they are automated bots or actual people – the option to edit their tweets could become another weapon in the disinformation arsenal used by bots and propagandists. Editing tweets could allow users to selectively distort what they said, or deny making inflammatory remarks, which could complicate efforts to trace misinformation. Twitter is a hellsite that also houses a vital time-stamped chronology of state corruption. It shows who know what and when, and gives some insight into why. Chronology is an enemy of autocracy. Altering Twitter is altering history, and that’s the appeal to autocratic minds.

Can you imagine the same sort of drama over The New York Times‘ copy editing desk making a subtle change to the paper’s correction policy? I cannot. And if a platform like Twitter wants to block an idea or opinion or author, it can do so almost completely, thanks to artificial intelligence and filtering technology. No, the moderation tools aren’t perfectly effective. But they can screen far more content than any human editor could ever review.

NOTE: I have been in the media and digital media business for 40+ years – almost all of my professional life. I am not arguing that traditional media isn’t powerful. But likening Musk’s control of Twitter to the impact of just another business tycoon trying to make their imprint on the world is naive. This is not the tech equivalent of Jeff Bezos buying The Washington Post or Marc Benioff scooping up Time magazine. And if we continue to see it that way, we’re going to be blinded by what comes next.

We have seen the power that individual decision-makers at social media companies can yield. We have seen how these companies have shaped elections, incited riots and genocides and enabled tyrants to spread misinformation. We have also seen these platforms used for good – for sharing important public health information, for giving marginalized people a voice.

And now, one man – with no shareholders and, I suspect, a very weak board of directors to rein him in – will have 100% control over a key outlet. That, to me, is unprecedented. So we must pay attention. And we should not rest easy simply because Musk has pledged his allegiance to “free speech”.

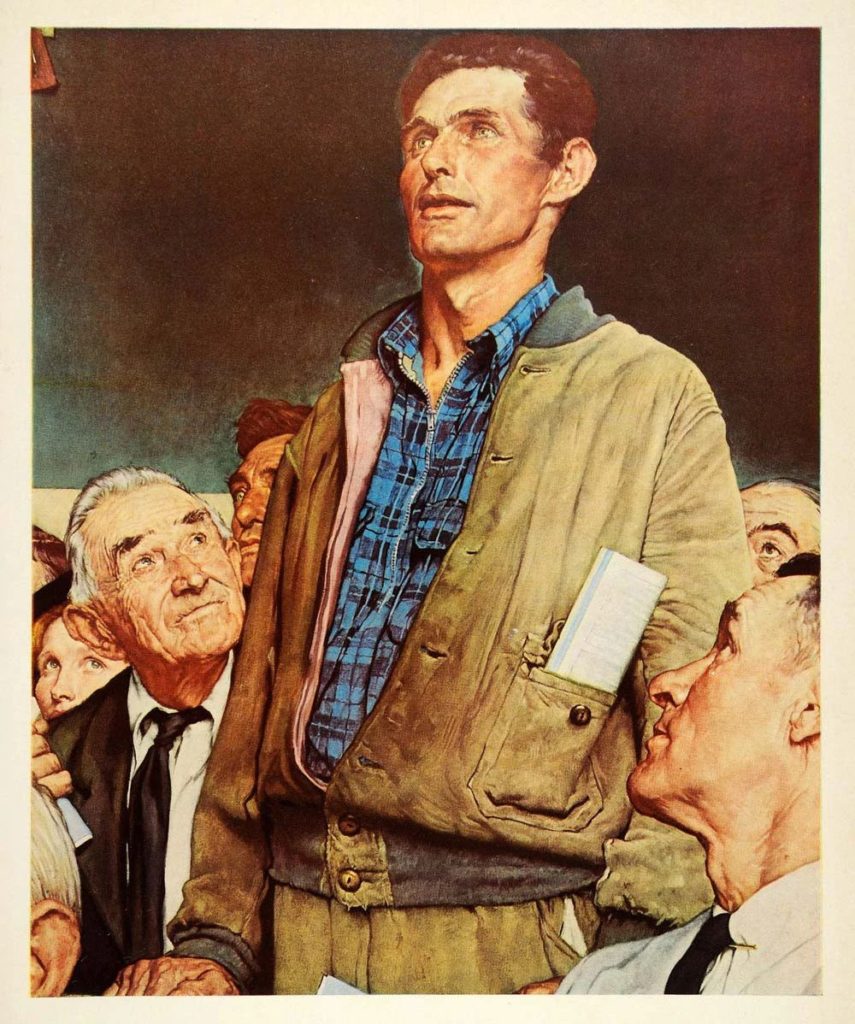

ABOVE: Norman Rockwell’s now famous 1945 paining “Vermont Man – Freedom of Speech”

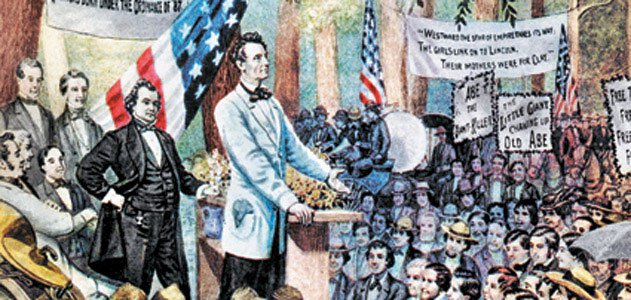

ABOVE: The Lincoln – Douglas debates in 1858

Ask almost any American what “freedom of speech” and honest debate means and she/he might refer you to something like the two classic graphics immediately above, or something similar. Intellectually-honest debate tactics meant pointing out errors or omissions in your opponent’s facts, or pointing out errors or omissions in your opponent’s logic.

Ah, the old days. Today bringing statistics and truth is fruitless “when you are in a meme fight” (quote from Renee DiResta, who studies pathological information systems and how narratives spread, and who steered me into some fabulous sources), where it is all about impugning the motives of a speaker, name calling, stereotyping, etc., etc. As that brilliant political pundit, Steve Bannon, said 4 years ago “the way you fight debaters is to flood the zone with shit”.

And Musk, Tweeting quite a bit about since Twitter approved his offer on Monday has been – well, mostly Tweeing shit. He’s twice called out Twitter’s top lawyer, Vijaya Gadde, suggesting that Twitter’s content-moderation decisions have a left-wing bias. The tweets led to a predictable pile on directed at Gadde and all kinds of racist language and threats; Musk feigned ignorance about the harassment when Twitter’s former CEO called him on it. His vitriol has led to about a dozen Twitter employees being harassed. He’s been doing a lot of replying to right-wing/anti-SJW/MAGA or MAGA-adjacent Twitter pundits like Dave Rubin, Mike Cernovich, and Ben Shapiro, signaling agreement with their “the left is unhinged” speech critiques.

A theme of Musk’s recent tweets has been restoring Twitter to a kind of political neutrality, one he argues will anger the right and the left equally. So far he doesn’t seem to have signaled any ways that his tenure might frustrate the right flank. On Thursday, Musk tweeted a meme that suggests that the left has shifted dramatically further left since 2008 while the right has more or less stayed the same, leading centrists to identify more closely with the right. The tweets attacking Twitter staff sound, as Casey Newton remarked, “less like Twitter’s future leader and more like a special counsel appointed by House Republicans to identify Bias in The Algorithm”.

Musk’s tweets reflect bad leadership and shitty behavior. But they also reveal a shallow understanding of speech principles and a wrongheaded or at least obtuse analysis of our current politics. That meme chart? It is, as dozens have pointed out, wrong, and the reality is certainly far more complicated. Similarly facile is Musk’s notion that Twitter’s free speech will comply with U.S. law, nothing more or less. In that case, Musk should be ready for Twitter to host virtual child-pornography videos (acceptible, via Supreme Court ruling) and all kinds of spam (which he purports to want to remove). Content moderation and speech laws: Combined, they’re a mess, and not often how they seem.

A fun thing about content moderation – the practice of social-media platforms deciding what we can and cannot say in some of the world’s most important online spaces – is that almost everyone thinks that it’s broken, albeit in different ways. Almost everyone also thinks that if you just put them in charge, they would fix things. When you’re the world’s richest man, you can actually give it a shot. And so, Elon Musk is buying Twitter, and a main reason is that he doesn’t like the company’s content moderation.

A peculiar fact about our modern public sphere is how much its borders depend on the whims of a few companies and their billionaire owners. A handful of people – mostly men and mostly in Silicon Valley – decide whether Russian state media should be allowed to have social-media accounts, whether a controversial post about the coronavirus can be amplified to millions of people or will be taken down, and whether the former president of the United States will keep or lose his most direct line to the global public. The executives who kicked Donald Trump off Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube early last year could’ve made those judgments by coin toss and no one could have done anything about it. The deliberation about whether to let him back on if he runs for president again in 2024 could be just as arbitrary. Millions of similar decisions – of differing levels of consequence – are made every day.

Our public sphere is governed by almost entirely unconstrained private power. As the internet has become ever more centralized on just a few major platforms, the impact of those companies over every aspect of our lives—politics, culture, the very way we speak—has kept on growing. Evelyn Douek, a Senior Research Fellow at the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, nails it:

Fine-grained and consistent content moderation is impossible on platforms that host hundreds of billions of posts a year. Optimists might argue that Musk is known for his ability to make seemingly improbable things happen: private space travel, mass-market electric vehicles. And some of Musk’s ideas for Twitter could open up new possibilities. He has said he wants to make the platform’s recommendation algorithm “open source” so that people can see what it is promoting or demoting. Many digital-rights activists and regulators have been calling for similar kinds of algorithmic transparency for a while. Platforms and policy makers should be thinking about new ways to empower users and the public in the governance of online spaces.

Watching this saga play out over Twitter, where each hastily composed Muskism is met with long, detailed debunks from people who mean well and know better, but who should probably also know better, has been frustrating. Researcher Renée DiResta captured the dynamic perfectly. As she noted above, it’s bringing stats to a meme fight.

It is both heartening and disappointing to watch lawyers, political scientists, historians, and experts in fields like content moderation and First Amendment law battle Musk’s missives in the replies. The spectacle represents the best and worst of Twitter, the platform. And shows the death of “the public square”. Charlie Warzel on his blog today:

“On one hand, you have people publicly putting their various esoteric bits of deep knowledge to use; if you follow enough threads and have the ability to identify the people with trustworthy credentials, there’s a good chance you’ll learn quite a bit about moderation, speech law, and mergers and acquisitions, and even something about political-polarization trends. On the other hand, you have a very wealthy boob speculating and bloviating with extreme confidence and attracting enough attention to force others to parachute in and mop up his rhetorical messes.

I understand why people are putting a lot of time and energy into bringing their stats to the meme fight. Elon has a great deal of money and power and a large audience that hangs on his words. When he says something dumb or wrong it makes sense to want to correct the record. For an academic or journalist or servant of the law, it very well might be the proper thing to do. But for a denizen of Twitter dot com, it is a mostly fruitless endeavor, and one that gives Musk what he wants – proof of outrage”.

Because now, “freedom of speech” really means “freedom of reach”. Anyone anywhere can say whatever they like in the zero-reach corner of their closets. Speech without reach isn’t free speech; it’s just mumbling to yourself.

And it’s simply not the case that freedom of speech is some legal binary switched between an abstract allow/not-allow state. Freedom of speech is now a continuous spectrum, a reach knob adjust by algorithms and tweaked by the companies where speech happens and the audience is. To think otherwise is to fall into the trap of thinking this is some Greek agora where you can either set up your soapbox next to Socrates and blab to your heart’s content or not, and how far your voice carries amidst the tumult is irrelevant.

There . is . no . agora . anymore. It is just what appears in most Twitter feeds, and algorithmic amplification (like it or not) is key to that freedom. It’s a gladiatorial arena.

Note that since the purchase, Musk only seems to reply to those already in agreement with him – in this case, people who believe that Twitter’s speech is heavily biased toward the left, or that liberals on Twitter seem to be freaking out way too much over his potential acquisition. So far, I haven’t seen him respond to the tweets from journalists and academics asking him to clarify his points or offering evidence that contradicts his claims. Given that it’s clear he’s reading at least the verified portions of his mentions, it’s safe to assume he’s not very interested in engaging with those arguments. Maybe that’s because his mind is made up for now. And so we get the memes, which are reductive.

But . that’s . the . point. The meme – unlike the nuanced, information-laden tweetstorm rebuttals – is immediately legible to a wider audience, and also more engaging. By the time the claim is debunked, Musk and his fans have moved on. But the meme has created enough backlash that Musk can point to it and go, “See?! They’re going nuts … over a meme! They’ve lost it!”

We went through this with Donald Trump. Charlie Warzel:

Trump’s tweets not only enraged legions, prompting a backlash that Trump and MAGA influencers would then use to rile up their bases, they also created their own little (mis)information economy. Both Trump haters and lovers would race to be among the first people to reply to one of his tweets in the hopes that Twitter’s weighted reply algorithm would put them in the valuable engagement real estate directly below his original message. Scammers, pundits, trolls, and even media companies tried to surf the Trump wave of engagement for a little amplification, which meant, of course, directing attention at Trump himself. There is an enticing but very slim upside to engaging with an attentional black hole like Trump or Musk on Twitter. You probably won’t get what you want, but they will.

The argument I’m inclined to make is that one should not engage with Musk and his arguments on Twitter. Yes, he’s a smart businessman involved in some big, exciting companies, but he appears at present to have none of the competencies or expertise to run a social network. He’s shown repeatedly this week that he doesn’t know what he’s talking about. Yes, that’s concerning—but also, no, you don’t have to be the one to educate him. In fact, Musk is not yet the owner of Twitter and the deal could still fall through. So right now, Musk’s opinions on Twitter are just … one man’s (simplistic) opinions! So maybe there’s no good outcome from engaging and giving him the opposition that he craves and expects.

But his words have consequences. His tweets are leading to harassment of Twitter employees (mostly women and people of color). His engagement with a bunch of trolly right-wing accounts and his winking plans for a less moderated Twitter have been a signal for far-right influencers to return to the platform, and they have in mass. People are genuinely worried Musk might roll back some of the rules that Twitter has put in place and that people might actually suffer on the platform as a result. Musk, after all, is “a bullshitter who delivers” (Benedict Evans). There is an understandable desire to shame Musk and to protest his behavior. It’s easy to feel powerless when the world’s richest man decides to buy one of the most consequential technology platforms for political speech on the internet. Few people want to sit back and shut up about it.

And so we are in a real bind. Broadly speaking, in an attention economy there’s no satisfying way to deal with people like them. There’s a circular thing where they command attention because they have some kind of power (fame, money, etc.) but, increasingly, their ability to command attention also grants them power (to influence/program the news cycle, amass cult-like followings, enhance their businesses). A few financial experts have recently suggested that a portion of Tesla’s financial success could be connected to his larger-than-life personality – which is most visible on Twitter. Here’s Lily Francus, the director of quant research at Moody’s Analytics, on Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast this week describing this phenomenon:

Obviously you have individuals like Elon Musk who are very, very talented at staying in basically the news cycle. And I do think fundamentally that a significant fraction of Tesla’s value is due to the fact that Elon can command this attention continuously.

I can’t know Musk’s true reasons for buying Twitter but it does seem like the purchase only pushes him further into the political and cultural news cycles. As the potential steward of a major platform for speech, his every missive increases the amount and intensity of attention heaped on him. Is that good for driving up the value of his companies? I don’t know. He could royally mess up Twitter or alienate himself so far from progressives that he could do unforeseen damage. Or, his full ascendency into Person Who Everyone Has Strong Opinions About could be beneficial to his ego and his businesses.

Watching Musk form a juvenile and simplistic cultural and political worldview one tweet at a time is deflating – given all his resources and potential to attend to the world in a way that’s positive for society.

And, personally, Twitter and Linkedin are the only social media platforms I use, and I’ve long characterized my use of Twitter as a devil’s bargain. The platform has benefitted me in certain ways, but this has come at a cost. The benefits and costs are what you would expect. I’ve made good connections through the platform, my writing has garnered a bit more of an audience, and I’ve encountered the good work of others. On the other hand, I’ve given it too much of my time and energy, and I’m pretty sure my thinking and my writing have, on the whole, suffered as a consequence.

And I have found I agree with Lawrence Sacasas (who blogs about technology, culture and ethics) that Twitter:

“is a tool akin to the Ring in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. The analogy first occurred to me with reference to then president-elect Trump’s use of Twitter to master all other forms of media. This remains true, but not only of Trump. Drop the Tolkien reference if you like, but Twitter’s power, as is widely acknowledged, is not in its relative size as a platform but rather in its ability to beckon our collective attention, whether we are on the platform or not, by focusing the attention of journalists, politicians, celebrities, pundits, academics, and other key refractors of our collective attention”.

Bottom line: the challenge Twitter presents to political culture might be framed as an unrelenting hostility to opinion. I have in mind Hannah Arendt’s discussions of fact, opinion, and truth in relation to politics. As I understand her, Arendt argues that claims of truth preempt the deliberation and debate essential to democratic governance. “Every claim in the sphere of human affairs,” she wrote in Truth and Politics, “to an absolute truth, whose validity needs not support from the side of opinion, strikes at the very roots of all politics and all governments.” Further on, she adds, “The modes of thought and communication that deal with truth, if seen from the political perspective, are necessarily domineering; they don’t take into account other people’s opinions, and taking these into account is the hallmark of all strictly political thinking.” But facts “must inform opinions,” Arendt grants.

On Twitter, facts and truth collapse into one another and opinion gets squeezed. And the proliferation of information blurs the line between fact and opinion by rendering facts matters of opinion.

I’ll leave it there. I have more to think about this weekend than the shenanigans of yet another rich person, and the endless torrent of conflicting information, and the silty sludge. I want to continue to address the incredible power of technology in war, in Ukraine, with my next major war piece due out this Monday.

Enjoy your weekend.