Russia continues to benefit from its stranglehold over Europe’s energy supply

28 April 2022 – Russia has nearly doubled its revenues from selling fossil fuels to the EU during the two months of war in Ukraine, benefiting from soaring prices even as volumes have been reduced. Russia has received about €62bn from exports of oil, gas and coal in the two months since the invasion began, according to an analysis of shipping movements and cargos by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. For the EU, imports were about €44bn for the past two months, compared with about €140bn for the whole of last year, or roughly €12bn a month. The findings demonstrate how Russia has continued to benefit from its stranglehold over Europe’s energy supply, even while governments have frantically sought to prevent Vladimir Putin using oil and gas as an economic weapon.

The Guardian provided a good overview of the situation and I have permission to repost it, with the original links, which follows … ending with my Postscript on why sanctions just never work.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Even though exports from Russia have been reduced by the war and sanctions, the country’s dominance as a source of gas has meant cutting off supplies has only increased prices, which were already high because of tight supply as global economies recovered from the Covid-19 pandemic. Crude oil shipments from Russia to foreign ports fell by 30% in the first three weeks of April, compared with rates in January and February, before the invasion, according to the CREA data.

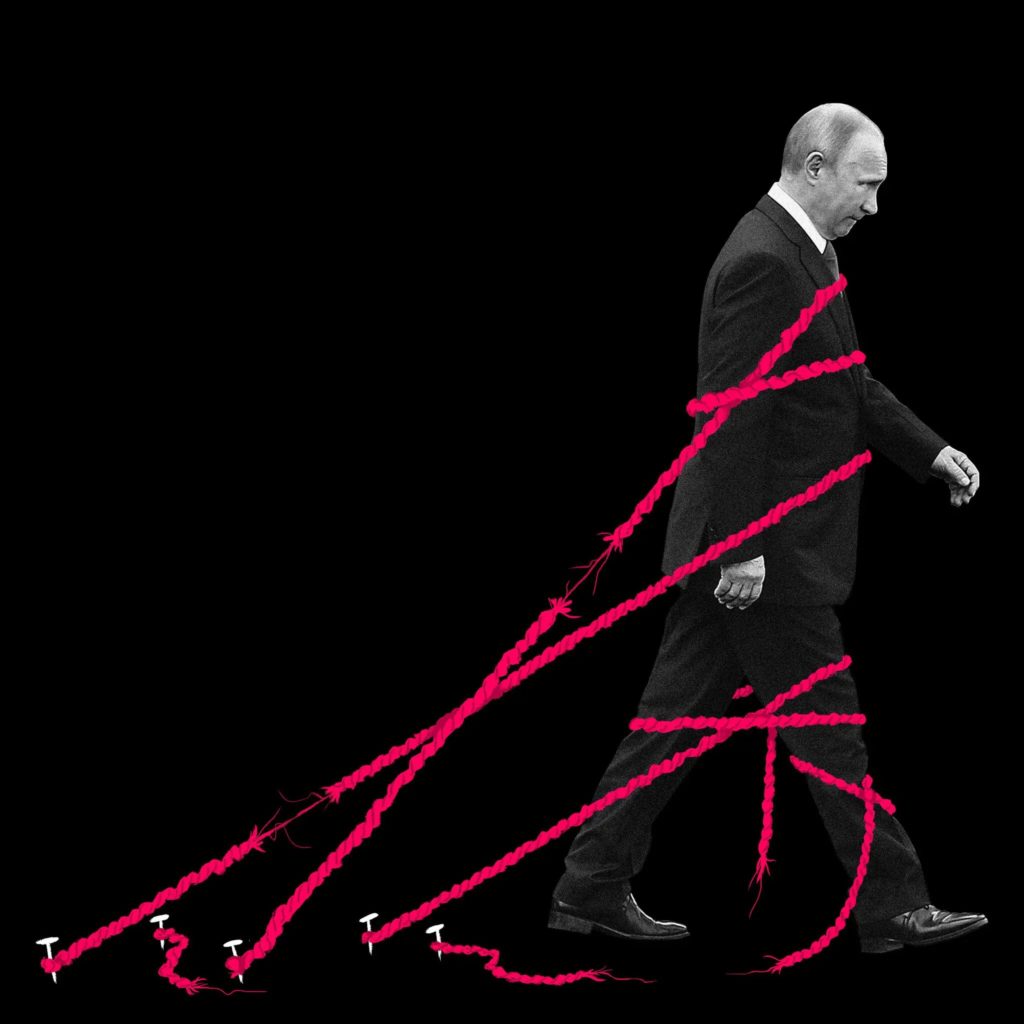

But the higher prices Russia can now command for its oil and gas mean its revenues, which flow almost directly to the Russian government through state-dominated companies, have risen even while sanctions and export restrictions bite. Russia has effectively caught the EU in a trap where further restrictions will raise prices further, cushioning its revenues despite the best efforts of EU governments.

Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst for CREA, said the cash propped up Putin’s war effort, and the only way to disable his war machine was to move rapidly away from fossil fuels. “Fossil fuel exports are a key enabler of Putin’s regime, and many other rogue states,” he said. “Continued energy imports are the major gaps in the sanctions imposed on Russia. Everyone who buys these fossil fuels is complicit in the horrendous violations of international law carried out by the Russian military.”

Russia’s revenue from fossil fuel exports soared to €62bn in the first two months of the country’s war against Ukraine

Russia in recent days has moved to cut off fossil fuel supplies to Poland and Bulgaria, which has provoked outrage.

Louis J Wilson, senior adviser at campaigning group Global Witness, said Russia’s willingness to violate its own contracts meant businesses now had no excuse for continuing to trade with Russia. “Fossil fuel majors and commodity traders who have continued trading in Russian fossil fuels, claiming that they are forced to do so by their long-term contracts, should take note of the value of the agreements they hold with Russian entities. Russia is willing to tear up these contracts to support their own war effort, yet European companies supposedly feel compelled to continue financing war crimes out of respect for them,” he said.

“The corporate enablers of this deadly trade have shown they will stop at nothing to continue profiting from Russia’s blood oil.”

CREA’s data found that many fossil fuel companies continued to do high volumes of trade with Russia, including BP, Shell and ExxonMobil.

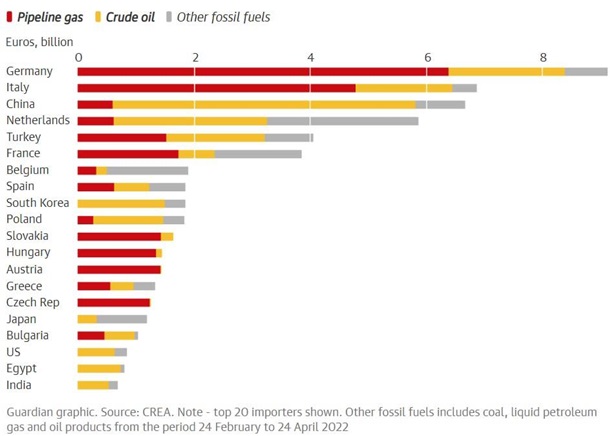

Germany was the biggest importer in the last two months, despite repeated avowals by the government that halting dependence on Russian oil was a priority. The country paid about €9bn for imports during the period. Italy and the Netherlands were also big importers, with about €6.8bn and €5.6bn respectively, but as those countries operate major ports, which take in products for refining and use in the chemical industries as well as for domestic consumption, many of those imports were probably used elsewhere.

A spokesperson for Shell told the Guardian that the company had taken decisive action in response to Russia’s war on Ukraine. “We have announced our intent to exit our joint ventures with Gazprom and related entities and to phase out all Russian hydrocarbons, in consultation with governments. Since we announced this intent, we have stopped all spot purchases of Russian crude, liquefied natural gas and of cargos of refined products directly exported from Russia.”

And a spokesperson for Exxon said: “We support the internationally coordinated efforts to bring Russia’s unprovoked attack to an end, and we are complying with all sanctions. We have not made any new contracts for Russian products since the Russian invasion, and there are no deliveries of Russian crude or refined products currently scheduled for the UK. We will not invest in new developments in Russia.”

“Two months after Putin invaded Ukraine, Germany is still funding the Russian war chest to the tune of €4.5bn a month. Berlin is the largest buyer of Russian fossil fuels,” Bernice Lee, a research director at the Chatham House thinktank, told the Guardian. “The world is looking to Germany to demonstrate strength and determination towards Russia, but instead they’re bankrolling the war and blocking a European embargo on Russian oil.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Sanctions alone – at least any sanctions that European countries would be willing to now consider – will not bring Russia to its knees any time soon. As long as Europeans still depend on Russian oil and gas, Russia will be able to depend on significant income from that relationship. The spat over whether gas deliveries will be paid in rubles, as Russia has demanded, only highlights the bind that European countries find themselves in.

The oligarchs who are losing their yachts and the people who are tightening their belts have little sway over the Kremlin. In Russia, with average citizens, Putin has grist for a loud “I told you so” about the West’s purported longing to bring down Russia.

Will the sanctions imposed by the Group of 7 nations truly isolate Russia? No. A number of countries, including Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and, most significantly, China, remain on friendly terms with Russia. The fact that this list also includes archrivals Pakistan and India, as well as Iran and Israel, illustrates Putin’s influence as an arms dealer and a power broker in South Asia and the Middle East.

So, while sanctions can hobble economies, they rarely compel the kinds of wholesale political changes that American officials would like to see. Research has shown that they produced some meaningful changes in behavior about 40 percent of the time. Change is unlikely to occur when sanctions are imposed without communicating the steps that must be taken for them to be rolled back.

Yes, it is too early to know how history will judge this unprecedented, sweeping effort to make Putin pay a price for his war. Nor can we predict the unintended consequences these sanctions may produce in the coming months or years. But there are lots of indications that the war — and the sanctions it triggered — could last a long time. As it is wise to have definite goals and an exit strategy when a country enters a military conflict, the same is true for waging economic warfare.

Yes, the United States and its allies have been wise in tightening the economic screws on Russia – so long as they bear no illusions about what this can and cannot achieve.