There is a reason why leaders won’t tell Europeans to put on a sweater to beat Putin. National and international agencies, but few politicians, are calling for people to cut their energy use.

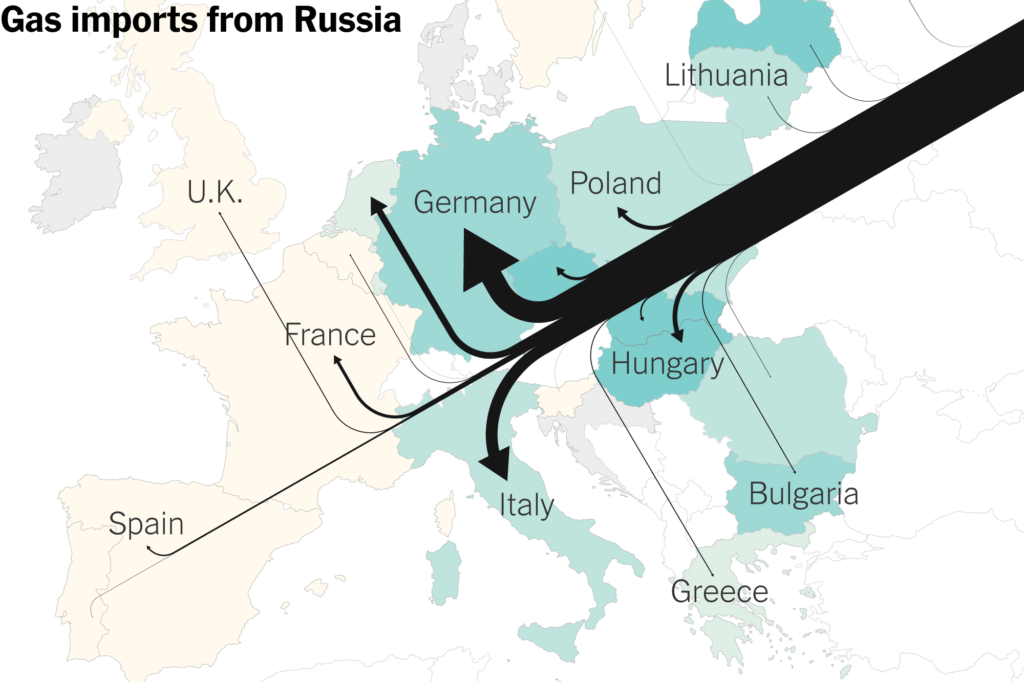

31 March 2022 – Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has created an energy crisis of unprecedented levels, as reflected in the rapid increase in commodity prices. European countries and the United States have responded by sanctioning Russia, and Germany has halted certification of the Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline. Concerns about the extent of Europe’s energy reliance on Russia, particularly for natural gas but also for coal and oil, are rising as the conflict worsens.

Reducing Europe’s dependence on Russian gas has been widely discussed for the past 15 years in Brussels. Despite alarm bells from a January 2009 crisis that led to the disruption of Russian gas transiting through Ukraine for two weeks and Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Europe has not stemmed natural gas imports from Russia. In contrast, Russian pipeline gas deliveries to Europe increased post-2014, and Europe also started importing Russian LNG from the Yamal LNG project, which started in 2017.

It is an aspect of the war I have not discussed because it is far outside my competency. But I had a discussion with a member of the Center on Global Energy Policy, a formidable group out of Columbia University in New York City, which has done a deep dive into Europe’s dependence on Russia and how this adverse relationship developed (a long and convoluted history and really deserves a long post).

We did discuss numbers. In 2020, Europe, including Turkey, imported about 185 billion cubic meters (bcm) of Russian gas which equates to about 36 percent of Europe’s total gas demand of 512 bcm. But mainly the discussion was about politics.

And it boils down to this. No one wants to be Europe’s Jimmy Carter. As Europe struggles with an energy crisis triggered by Russia’s war on Ukraine, few politicians are keen on telling their citizens to cut their energy use. Germany’s Economy and Climate Minister Robert Habeck on Wednesday became a rare exception when he told his fellow citizens:

“We are doing the utmost. Do the same. Save energy. With a great community effort by the government and the people in this country, the companies and the citizens, we can already become more independent from Russian energy imports.”

According to the Columbia group, the EU sends about €800 million a day to Russia for oil and gas imports. Obviously the Ukrainian government wants that stopped, arguing the cash is helping fuel Vladimir Putin’s war machine. But most EU governments are loath to risk their economies and the ire of their voters even when confronted with bombed Ukrainian cities and dead civilians. It’s not that there’s a dearth of ideas. The International Energy Agency (IEA) and the European Commission have put forward a smorgasbord of policies in recent weeks. These include lowering thermostats in homes by a degree to cut gas consumption and slashing oil demand by cutting speed limits, introducing car-free Sundays, offering free public transport and getting people to work from home.

SIDE NOTE, JUST TO SHARE SOME CREDIT: The IEA said its measures could cut EU oil demand by 6 percent in four months and Russian gas imports by a third by the end of the year, while the Commission has proposed its own cluster of actions it says could slash demand for Russian gas by two-thirds this year. National government agencies have also echoed the IEA. Germany’s federal environment agency said earlier this month that turning down thermostats by 2 degrees would reduce Russian gas imports by 7 percent.

And on Monday the president of the French energy regulator, Jean-François Carenco, joined the chorus of voices calling for measures to cut energy — which, as Habeck also pointed out, would have the side effect of saving people money: “Whether it is by lowering the heating, the air conditioning, the lights, there is an emergency and everyone must make an effort”.

But politicians are being quite careful in what they’re asking people to do. Habeck on Wednesday suggested that Germans turn down their thermostats by a degree or two, acknowledging that his appeal might sound “disproportionate” to those struggling to pay surging energy bills. And last night EU competition boss Margrethe Vestager, at a presentation, said “Control your own and your teenager’s showers. And when you turn off that water, and then you can say: ‘Take that, Putin!’” Ummm. Ok, Margrethe. Go get him.

Behavioral change is never an easy sell from government, especially for a continent that has gotten – how shall I say this – fat and lazy. And there are cautionary tales for politicians.

The Carter criterion

From the explosion of popular rage in France at fuel price increases that sparked the Yellow Jacket movement in 2018, to the PR disaster that followed former U.S. President Carter’s call for Americans to pull on their sweaters to cut energy use during the 1970s oil crisis – Carter was politically crucified. The disagreement and resistance comes really from a deep, underlying sense of: ‘I don’t want other people to interfere with how I live my life!!” Just scan Twitter. And not just “English” Twitter. French, German, Italian, etc. Twitter. So it is politically safer for politicians to challenge Russia by building wind farms and boosting solar panels – measures that many EU governments have backed.

Even tepid calls for a change in behavior don’t go over well. Not long after Russia’s invasion, French Economy Minister Bruno Le Maire said everyone must “make an effort” to cut their personal energy use and create “total independence in terms of energy”. But that saw him bashed by the far right. With an election at home looming, the administration of French President Emmanuel Macron is now even more cautious. Example? When she co-launched the IEA’s oil demand roadmap earlier this month, French Minister for the Ecological Transition Barbara Pompili would only say it contained “some interesting ideas.”

Although politicians are nervous, the Columbia group noted many opinion polls have shown strong support for action against Russian imports. Surveys earlier this month found around half of Germans support an energy embargo, something the government doesn’t back – although later another survey found two-thirds opposed this measure. Eh, polls.

But avoiding the issue of reducing consumption is doing Europeans a disservice. It’s failing to actually help consumers make the link between their energy bills, the energy insecurity that we are potentially facing and the war in Ukraine. You’d need a mix of clear messaging and financial incentives could make voluntary energy-saving “palatable” to consumers. Better than reaching a point where you need to actually restrain consumption.

But that requires political leadership, abandoning selfishness … and we’ll get that when pigs fly.

Oh, and about those oligarch sanctions …

My readership tends to be a pretty savvy group so my guess is most of you have read that private jets linked to Russian oligarchs and officials appeared to continue flying into and out of EU and UK airports despite flight bans and sanctions imposed after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Guardian had a story on it, and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project had an extensive report over this past weekend. As I noted when the oligarch sanctions were levied, it was all just public theatre.

One of my OSINT sources told me it is easy to track all of these flights using such sources as the flight tracking service Flightradar24. Doing so he tracked all sorts of private jets in and out of Helsinki, Geneva, Milan, Munich, Paris, etc. The data and records you can access show ownership of the jets but do not show details of who was on board the plane.

And then there are the big players who completely avoided sanction. Governments were apparently reluctant to disrupt markets where super-rich oligarchs are big players. There are 4-5 tycoons who are the wealthiest of the oligarchs (total net worth exceeds $700 billion) who were not sanctioned anywhere.

Why not? Sanctions experts say it’s mostly due to their critical stakes in vast energy, metals and fertilizer companies. Some might be too far from the center of Kremlin decision-making or too difficult to sanction, but mostly it is due to markets. The U.S. learned the hard way in 2018 when it sanctioned billionaire Oleg Deripaska, who controlled the world’s largest aluminum company outside China. That caused global prices to soar, only stabilizing after Deripaska decided to move on and sold his interest in the company in 2019.