Google has announced it’s developing new “privacy-focused” replacements for its advertising ID. But curb your enthusiasm on this, as it’s not coming for (at least) two years. And Facebook’s reaction is – well, don’t forget that Google and Facebook are presently facing a lot of scrutiny over some pretty solid-looking claims that they colluded over ad pricing.

And Apple? Well, Tim Cook has pretty much robbed the mob’s bank, hasn’t he?

In Part 1 I discussed how Facebook and Mark Zuckerberg are suddenly boxed in due to a number of issues, especially with U.S. state regulators seeing Facebook vulnerability and blood in the water.

In Part 2 I discuss in more detail the paradigm shifting issues.

17 February 2022 (Athens, Greece) – Ah, the simple days. In the beginning, e-commerce was very utilitarian. You knew what you wanted before you turned on your PC, you clicked on it and you bought it. The first really successful organizing layer on top of the web, search, was also very utilitarian and, of course, so was the first big online advertising model, which was explicitly based on search. But ever since then, e-commerce, discovery and advertising have been moving and expanding across the spectrum – expanding from utility to experience, and from search and lists to suggestion and discovery.

The global advertising business is now worth about $600bn a year, and at least half of that (and growing) is digital. A huge chunk of this is now being overturned, due to regulation – like the European Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Protection Act (CCPA) – on one side, and the duopoly platform companies (Chrome, iOS) on the other. Cookie-based, cross-site, third party tracking is going to disappear (well, in some manner), as is some of the related tracking that had been built into iPhones such as the Identifier for Advertisers (IDFA) which is a random device identifier assigned by Apple to a user’s device.

Yes, you can advertise based on what’s on the page (“context”), and you can advertise based on what else someone did on your site (“first party”), but advertising based on what someone did on another site (3rd party, those bloody cookies) is going to look totally different. What does that mean? How different? No one quite knows. It’s all fluid, something-in-progress.

Obviously, no one actually likes cookies. In the last 25 years, the adtech business built a vast inverted pyramid of complexity, obscurity, rent-seeking, arbitrage and occasional fraud on top of cookies, which were never really designed for any of this. That also brought a lot of privacy problems, only some of which were inherent to the underlying business purpose (“show relevant ads and measure ROI”). Now all that’s going away – well, kind of. As I noted, it is all a bit hazy.

But over the last decade or so we have been pounded by the new moral view of “tracking”, and a great deal of political advocacy (“ban targeted ads!”), but we have not really had any good public conversations around what will happen next, or even what we want. And that has offered all kinds of opportunities for Big Tech. I have bunches of questions and these are just a few:

• So we seem to be excited that we are transferring targeted data directly from advertisers to platforms, which is at least “theoretically” consent-based, so does that solve all those pesky GDPR and CCPA like questions?

• Indeed, this will stop third party data and cookies, where we track people across different sites, leaving only first party data — where Apple, Google or the New York Times will track you within the same service — so I guess that’s not considered “evil”?

• How much advertising will move to purely contextual targeting? Could you make a federated signed-in model across multiple sites and thereby convert 3-party to 1st-party data, or has the privacy campaign basically killed the competition campaign?

• And what does all of this mean for the relative efficiency and market power of the biggest sites with the most context and the most first-party data – isn’t this all pretty great for the oligopolies? And which ones, in particular?

Plus, as I have detailed in numerous posts, location tracking is really quietly, sometimes surreptitiously, baked into the web’s modern data collection regime. Apple, Facebook and Google have created a network of commercial surveillance with their tracking technologies. The practice of third-party tracking on websites has become so widespread and complicated that special software is needed to understand and track this modern data collection regime. For a brief introduction to how this works read a post I published two years ago which needs an update but the basic principles are all still current.

What we have seen in recent years is significantly enhanced information sharing and networking capabilities among smartphone users, advanced by geospatial technologies which have undeniably permeated almost all aspects of modern life in our society. Social media apps are increasingly location-based, providing analysts with access to a wide range of shared spatial data, such as check-ins, geo-tagged images, video clips or text messages, or reviews of businesses and other localities.

OK, there is a positive impact. Based on these data, research studies provide valuable insights into spatio-temporal aspects of marketing, event detection, political campaigning, disaster management, migration, transport, natural resource management, human mobility, urban planning, tourism, epidemics, and communication. But let’s ignore “the good” for the moment.

This has led to the creation of a new discipline I have written about before – geospatial data science. It is a transdisciplinary field that extracts knowledge and insight from geospatial big data using high-performance computing resources, spatial and nonspatial statistics, spatiotemporal analysis models, GIS (Geographic Information Systems) algorithms, machine learning methods, and geovisualization tools. It is also why we’ve seen the emergence of a geospatial cloud and the building of a comprehensive cyber infrastructure.

And it is why we are only at the infancy of cloud computing. What we are seeing now is only the beginning of a long-term explosion in use – and Big Tech earnings. Companies are geared to spend a trillion dollars on cloud services over the next 5 years, meaning that there is a lot more room for tech companies to keep growing. And “Big Tech”? I think when it comes to anticipating the future for Big Tech, we weren’t thinking big enough.

So for “The Horsemen of FAAMG” .. Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Google … it has meant a seamless technology stack which includes a geodata hub for sharing assets and facilitating community engagement, cloud services, online analytic tools, real-time big data processing, and a nice set of presentation options. “Location intelligence” in the trade. And while location intelligence can be gleaned from social media enriched with locational clues, mined to a high degree, developers have realized that advanced geospatial / geographic information systems are foundational and not an add-on so they need to be baked into operating systems.

Yesterday Google unveiled proposed rules to limit how advertisers track more than 2.8 billion people using phones powered by its Android software, but the company is taking a different approach than that of Apple, which restricted iPhone ad tracking last year. Let’s take a look at Google first.

My personal blog listserv (of which you, dear reader, are a member, and who now number 23,000 strong) is weighted heavily toward the advertising, digital media and mobile industries (53% of my list) with about 9% of you self-tagging as being in some aspect of data privacy.

So I spent a good part of my day yesterday and today chatting with a number of members steeped in the app-tracking ecosystem about Google’s new proposals and found there seemed to be a consensus there are 4 key distinctions from Apple’s rules. There’s also one way in which they are similar: both will hurt Facebook owner Meta Platforms and the advertisers who buy ads through the social network. Hours of conversations, text messages and emails so I’ll try to summarise the key points.

1. Google will take a more hands-on approach to controlling what data advertisers access than Apple

Apple set broad guidelines for how app developers could comply with the new iPhone restrictions without getting kicked out of the App Store. That has caused app developers and ad platforms to adopt varying interpretations of the letter and spirit of Apple’s rules, raising questions about whether and how Apple is policing the system.

By contrast, one of Google’s proposals would implement a system in which apps could wall off certain data from transmission to third parties, such as firms that help app developers sell ads and track how the ads performed. Another proposal would have Android devices analyze consumers’ app usage to create high-level topics the person is likely interested in, such as travel or fitness. Google would then share those topics with advertisers so they would still have some data to inform their ad spending.

The new proposals could also limit app developers’ ability to use common methods to identify users and target ads to them even when they opt out of certain types of ad tracking on their Android devices. Today, Google’s Android privacy settings allow users to opt out of interest-based advertising and ad personalization on the device. But some app developers rely on a common method known as fingerprinting, in which they use a device’s IP address to identify and track users. Google’s new proposal could prevent that. Apple has said its privacy rules forbid fingerprinting.

2. Android owners are unlikely to see “Ask app not to track” prompts as iPhone owners do

While Apple required developers to serve a prompt asking iPhone users for permission to track them for advertising purposes, there is no mention of a similar system coming from Google. More than 80% of iPhone users click the button to disable tracking when they see it, according to mobile measurement and data firm AppsFlyer. Users who opt out of tracking ask apps not to share a unique identifier – tied to their device – that app developers can use for ad purposes.

On Android, Google appears likely to phase out the use of that unique ad identifier. Anthony Chavez, vice president of product management at Google, said in a video about the new privacy proposals that the overarching goal was to “remove the need” for advertising that relies on identifiers. Chavez’s comment suggests Google is crafting an entirely different system for tracking and targeting users on their mobile devices while at the same time cutting down on the amount of consumer data the millions of Android apps can collect and share about their users.

One of my readers noted Google’s approach here is not to belabor consent from users as Apple does, but to file the teeth of any data sharing that could occur on its platforms. She said by doing so, Google can avoid “another Cambridge Analytica,” a reference to the now-infamous research firm that obtained user data from Facebook without the users’ consent.

3. Google is taking a slower, gentler approach than Apple

I read the press releases and watched some of the Google announcements and it seems Google went out of its way to reassure developers that any major changes would happen after plenty of notice. In its big blog post announcing the Android privacy proposals, Google said any big changes were at least two years away, and, without naming Apple, it criticized the approach that “other platforms” have taken as blunt and ineffective.

And an important point noted by another reader. Because of Google’s business model and its $200 billion–revenue ad machine, the company has a greater incentive to take a more collaborative approach with app developers and advertisers. It plans to seek feedback on its proposals over the coming year and launch a test of its proposals by the end of the year. Google is developing its privacy efforts on Android alongside its work on phasing out web trackers, or third-party cookies, on its Chrome browser. Some of the proposals published Wednesday mirror the work done by Google’s Chrome team, including the creation of a system to target consumers based on topics they are interested in, as determined by what they’ve looked at. Google introduced the Topics proposal in recent weeks (which I covered in detail here) after a prior proposal for an alternative to Chrome cookies faced heavy criticism from privacy advocates and ad industry members alike.

Part of Google’s slowness in making changes to Android and Chrome comes from its concern over rivals’ allegations that changes limiting their ability to track users would work to Google’s advantage. Because of the sheer volume of data Google knows about people from Search, Android, Chrome and YouTube, which other app developers don’t have access to, new restrictions could make it harder for developers to prove the ads they sell are working. That could cause advertisers to spend even more money with Google versus competing apps – a topic I covered ad nauseam in my GDPR screeds when I noted that the EU regulators simply did not “get” how any of this advertising and digital world worked and had suggested nothing stops these platforms from upturning the cart in their favor.

The more Google becomes “privacy friendly”, the more arguably advantaged they are themselves because it’s a walled garden.

4. Like Apple’s iPhone rules, Google’s changes are bound to hurt Meta

The recent iPhone privacy changes made it hard for Meta, one of the biggest mobile ad sellers, to prove to advertisers that their ads are working. The toll from Apple’s changes became clearer in recent weeks, as Facebook parent Meta told investors the rules would erase $10 billion in revenue this year because they hurt the company’s ability to prove to advertisers that the ads they buy are working. On Wednesday after Google’s announcement, Meta shares fell 2%, Snap’s stock price fell 3.4% and shares of mobile ad tech company AppLovin tumbled 9% – all of them sustaining steeper losses than the broader S&P 500 index.

As a result of Apple’s changes, some advertisers who buy ads on Facebook and Instagram, another Meta app, shifted their spending to the Android version of those apps. But Google’s eventual changes could similarly dampen the value of that ad spending and prompt even more advertisers to give up on Meta. One of my readers runs a company which provides business coaching and marketing services to large businesses in the wedding industry. He said he is spending 80% less on Facebook ads than he did a year ago because the impact of his ads declined after the new iPhone rules went into effect: “People are making it very clear they prefer not to have businesses and apps track their activity online. Our company is listening to what they’re telling us, which is really create better and more valuable content to draw us in organically”. To make up for decreased ad spending, he now attends more conferences, provides free educational tools and appears on podcasts to find new business. And it is working.

Publicly, Meta appeared to appreciate the slowness of Google’s approach. Dennis Buchheim, vice president of advertising ecosystem at Meta, said in a tweet Wednesday that it is “encouraging to see this long-term, collaborative approach to privacy-protective personalized advertising from Google”.

And as for when Google will finally make this change? Well, you all know me. I’m a cynic. I read an amusing write up called “Google Keeps Android Ad Tool Into At Least 2024, Exploring Other Options”. Google said it would give “substantial notice” before axing what is known as AdId. But it will immediately begin seeking feedback on its proposed alternatives, which Google said aim to better protect users’ privacy and curb covert surveillance, before it makes changes. But better than what? What happens if there are technical issues in 2024? Well, if they need more time to better protect users’ privacy and curb covert surveillance, of course. Gee, and here I was thinking it was Apple primarily marginalizing Facebook 😂

Last May Apple introduced a new ad unit to the App Store: a paid placement on its Search page. Rumors of this new unit had circulated previously, although the notion that Apple would increase the density of ad placements in the App Store was wholly predictable. Tim Cook had been hinting at it for over two years. Apple was expanding its mobile advertising platform in parallel with the rollout of the App Tracking Transparency (ATT) privacy policy, which presents meaningful commercial challenges to other mobile ad platforms and will likely diminish their operational efficiency.

What Apple has done, quite frankly, is rob the mob’s bank. In bolstering its ads business while severely handicapping other advertising platforms – but especially Facebook given its recent claim that it lost $10 billion dollars due to ATT – with the introduction of a privacy policy that effectively breaks the mechanic that those platforms use to target ads, Apple has taken money from a party that is so unsympathetic that it can’t appeal to a greater authority for redress. Apple has brazenly, in broad daylight, stormed into the Bank of Facebook, looted its most precious resource, and, camouflaged under the noble cause of giving privacy controls to the consumer, fled the scene.

And Facebook is left with little recourse. The company had attempted to sway consumer sentiment to its side through an enormously wide-reaching PR campaign, but its efforts were hobbled by the narrow messaging that was available to it. Facebook couldn’t explain in detail why ATT will harm consumers because, in doing so, it would need to reveal in a lot of detail just how it personalizes ads – through observing conversions on third-party websites and apps. So Facebook was restricted to a fairly weak PR strategy, which was to highlight that small businesses would be harmed by ATT.

This is true, of course, but it doesn’t invigorate a deep well of compassion from consumers. Does anyone want to acknowledge that their local florist or butcher is personalizing ads to them? Meanwhile, Apple simply had to mention “privacy” whenever objections to ATT were raised and mainstream media outlets rushed to defend it. The same crowd that embraced “Move fast and break things!”

Apple’s exploitation of leverage in this situation has been breathtaking. It’s important to note here that ATT allows users to opt out of tracking, which is a peculiar term that is defined in a very specific way. When a user opts out of tracking through the ATT prompt, that user prevents the app from co-mingling any data it collects with data owned by other parties for the purposes of ad targeting. Last year I explained why this particular privacy protection is, charitably, exaggerated, and, cynically, deceptive:

Apple’s strategy in deploying ATT. It has artificially defined “privacy” as the distinction between first- and third-party data usage. The the largest platforms simply entrench their market positions. Google owns search and Chrome, and Apple owns the App Store. If first-party data is the commodity of empire for digital advertising, then Google and Apple and various other large platforms fortify their empires through the “first-party mandate”: the decree that the use of first-party data in ad targeting is privacy compliant but that the co-mingling of first- and third-party data for ad targeting is not.

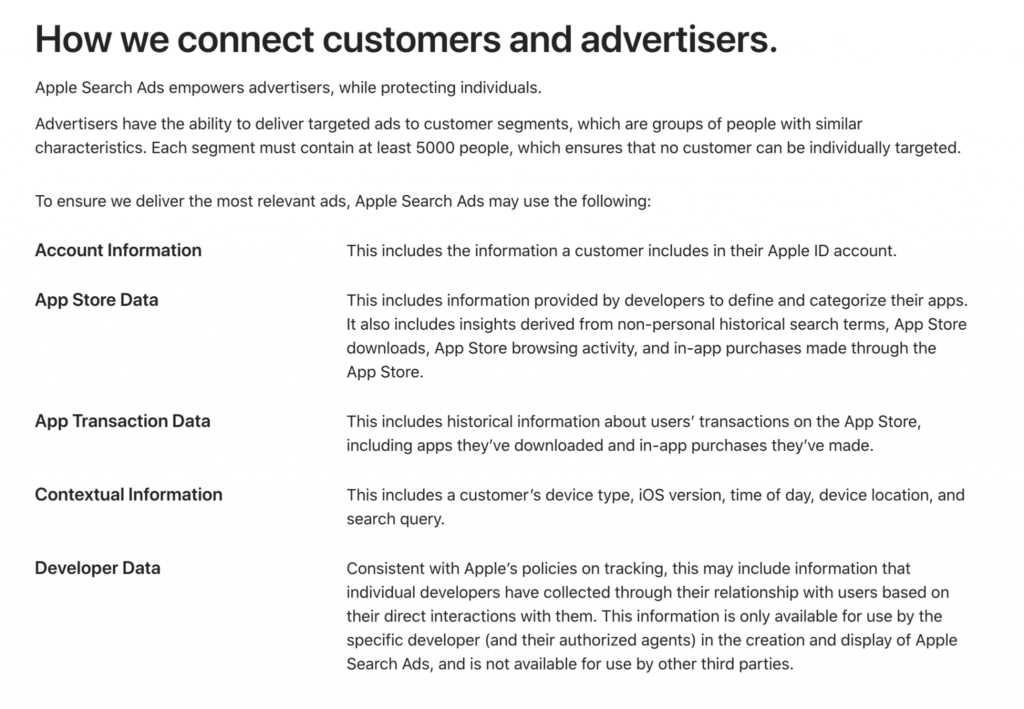

Note here that Apple is very public about the fact that it utilizes users’ app transaction data for the purposes of ads targeting. In the privacy documentation for its Apple Search Ads network, Apple details exactly what data is used to target ads to users, which it describes as “connect[ing] customers and advertisers”:

Apple uses data about in-app purchases that users have made and apps that they have downloaded to personalize ads. This data was previously available to other advertising platforms through the event streams they ingested from apps and websites via SDKs and pixels, but ATT will sever that access. Apple is using the particular definition of “tracking” — and a very generous definition of all transactions facilitated through the App Store as being first-party data — to capture advertising market share.

For the sake of intellectual honesty, it’s important to flag three facts here:

1. Apple has used the data identified above to target ads with Apple Search Ads since it was launched, so this isn’t new.

2. Apple isn’t alone in defining tracking in the way I describe above: so does the W3C, for instance.

3. Apple does not build user profiles for use in ad targeting. As Apple’s privacy documentation states, Apple puts users into segments on the basis of their behavior, in an application of differential privacy. Each segment must be comprised of at least 5,000 users before that segment can be targeted.

When only first-party data is permissible for use in advertising targeting, then the largest consumer tech companies will simply grow their first-party datasets. Apple is claiming that the entirety of the App Store exists in its first-party data environment and so every interaction that takes place in any app is fodder for its ads optimization algorithm.

But under these conditions, the exact quality and quantity of consumer data continues to be harvested and utilized for ads targeting under ATT as was utilized before ATT. Nothing has changed with ATT: a “Big Tech” company continues to monitor app usage and monetization for the purposes of targeting ads, except that with ATT, the company is Apple instead of Facebook. To a true privacy zealot — someone for whom any ads targeting is an ethical disaster — would this new privacy configuration of “First Party = Good, Third Party = Bad” be acceptable?

This is the odious specter of ATT: it’s an obvious commercial land grab dressed up as a moral crusade, and it will ultimately subvert the open web and the freemium business model. ATT doesn’t provide real consumer choice, and Apple has clearly privileged its own ad network with this new privacy policy in very obvious ways. And Apple has engineered all of this while being cheered on by parties that ape Apple’s commercial slogan regarding the righteousness of first-party data for ads targeting. Case studies will be written in decades to come about Apple’s astute attack on Facebook via an esoteric advertising identifier. If anything is clear from the (protracted) rollout of ATT, it is that Apple’s PR department deserves a pay raise.

Part of the challenge analysing all of this “need to regulate” requires looking at how much of the noise is “religious”, and full of wishful thinking. Ah, those politicians and regulators screaming hysterical stuff. My favorite continues to be the idea that “if we simply banned all tracking then we would solve problems of privacy, misinformation and radicalism on social media”. As though contextual ads would work differently. All platforms optimise for engagement and if you have been following this shift toward 1st party data and subscription services who’ll see it optimises for engagement just as well. This just reflects the opacity and complexity of the market and how so many just do not understand it.

But it also brings up the elephant in the room I have been writing about for 2+ years: advertising and data will retreat/have retreated inside silos (Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, TikTok, etc.) where nothing is passed around or shared. Taken to its logical conclusion, most of these privacy regulations will simply not apply.

So regulators: you really need to figure out just what in hell is the problem you are trying to solve and/or regulate.