Thomas and Henrietta Maria Bowdler and the works of William Shakespeare.

A short bit for the writers among us.

9 February 2022 (Crete, Greece) – Unauthorized changes to a text reside in the murkier confines of the copyright system, where, at most, moral rights may hold court. Our lexicon captures this mist: characterize such alterations as “expurgation,” distortion”, or “red-penciling”, and it may raise eyebrows. But call it “editing”, and furrows on one’s brow are less likely.

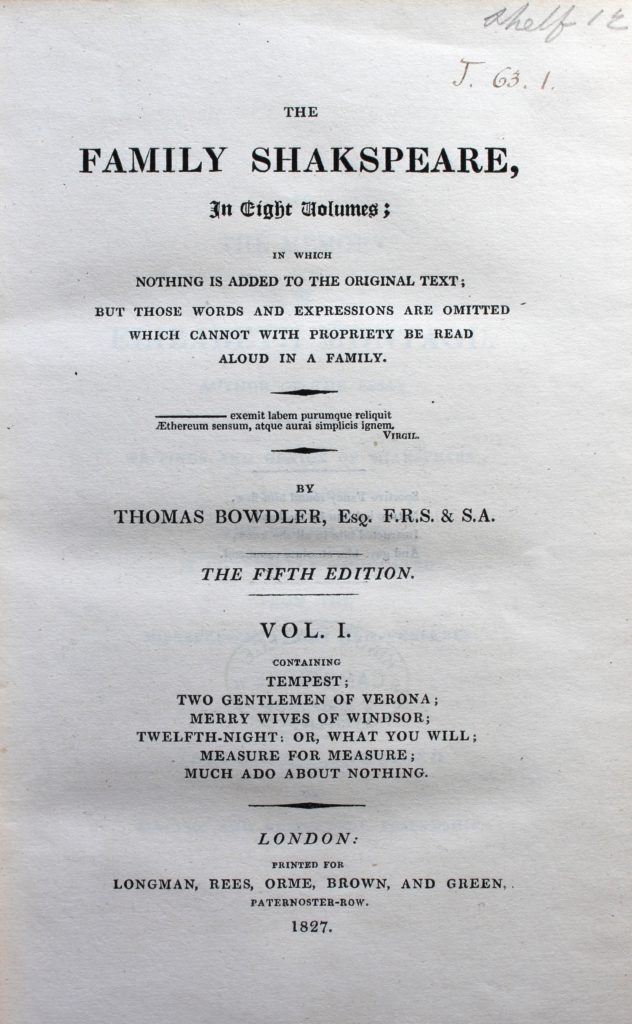

Within this lexicon there is one particularly curious synonym – “bowdlerization” (per the Cambridge Dictionary, “to remove words or parts from a book, play, or film that are considered to be unsuitable or offensive”). Whence, and why, this 19th century term? The answer discloses an engaging tale, which still has the power to instruct, where the works of William Shakespeare met pre-Victorian sensibilities of what was suitable, even in non-public spaces.

As a pure matter of etymology, “bowdlerization” derives from the family name of Thomas Bowdler (1754–1825), and his sister, Henrietta Maria Bowdler (1750-1830), both from a small village near Bath, England. Their father was a banker, Thomas as trained as a doctor, while Henrietta Maria moved in literary and related social circles. What brought together the two siblings was a book publishing project, The Family Shakespeare, first published in 1807, with a second edition published in 1818. Further editions followed.

As described in Smithsonian Magazine, Bowdler’s goal was to produce an edition of Shakespeare’s works

“in which nothing is added to the original Text: but those words and expressions are omitted which cannot with propriety be read allowed in a Family”. In other words, The Family Shakespeare was Shakespeare without the ‘indelicacy of expression’ the Bard often favored.

And so, “bowdlerizing” was born.

The article refers to a literary scholar, Adam Kitzes, suggesting that the general reservation of the Bowdlers regarding Shakespeare’s texts was that the works suffered from an overabundance of literary “realism”. So, to the literary ramparts went the Bowdlers. Their goal was to make contents suitable for a father to read aloud to his family without fear of corrupting the listeners, this against a sense that licentiousness was on the rise in early 19th century England.

In so doing, the sought to present a text that preserved Shakespeare’s “beauties”, while removing the “blemishes”. The result are texts that resemble the original, at least plot-wise, but without material phrases in places, or even entire plot events missing. The 1807 edition addressed twenty of Shakespeare’s thirty-seven plays, while the second edition included all thirty-seven of them.

How well do they do? The article reports that in the first edition, about 10% of the text was removed, with particular attention to avoid any whiff of religious irreverence. So

to avoid blasphemy, exclamations of ‘God!’ and ‘Jesu!’ were replaced with ‘Heavens!’ or omitted altogether. Or, Lady Macbeth’s plaintive entreat – ‘Out, damn’d spot!’ – was changed to ‘Out, crimson spot!’

Now, as for plot

Some of the changes were more drastic: the prostitute character in Henry IV, Part 2 is omitted, while Ophelia’s suicide in Hamlet becomes accidental drowning.

The degree of cooperation between Thomas and Henrietta Maria in producing The Family Shakespeare remains a subject of debate. It was once assumed that Thomas was the anchoring oar (despite he being a doctor, while Henrietta Maria was an already published author), but more recent examination suggests that it was a collaborative effort.

Some are of the view that Henrietta Maria initiated the project and took the lead in producing the first edition (even as her name was omitted from the title page). Thomas did so only for the later editions, starting with the 1818 edition. Even that may have been a smoke screen. Thomas may have championed his authorship “to avoid [Henrietta Maria] having to admit publicly to having understood the passages requiring removal.”

Irony was often a key feature of the literature of that period, and nothing could have been more ironic than the fact that the Bowdlers were fond, very fond, of Shakespeare. In publishing the book, they wanted to broaden the appeal of Shakespeare’s works to “vulnerable” readers, this by sanitizing the text (as expressed, to separate the “wheat” from the “chaff”).

In so doing, they hoped, The Family Shakespeare would encourage Shakespeare’s plays to be read aloud, even enabling a family to “perform” the play in their private setting. Bowdlerizing the text was a source of good, not something to be condemned.

Today, the term “bowdlerize” bears a pejorative connotation. It may not be in the league of book-banning, but doing so still is something to be frowned upon (“So what do your parents do? They bowdlerize books.”). Or not. The Bowdler siblings were earnest in their convictions, and they were not part of any government-sanctioned campaign of censorship. If you chose to acquire their book, you presumably knew what you were getting.

Moreover, as the article observes:

The Bowdlers, and the numerous copycat expurgators, were vigorously slapped down by a literary establishment that was concerned with the ‘authentic’ Shakespeare, who even then was seen as a unique genius. At once so exalted and yet so fragile, Shakespeare’s language had taken on such a sacred status that it was vulnerable to even the slightest touch.

This observation recalls a session I had a few years ago at the Frankfurt Book Fair about the use of a reproduction of an early 19th century painting, in a truncated form, as a contemporary book cover. There, the issue was the authenticity of a work of art in an age of mechanical reproduction. Here, while authenticity can also be raised regarding the literary work, mechanical reproduction is not of concern.

When there is no moral right varnishing on the text, can we speak of an “authentic” work of literature, which is exempt from any later alteration? Depending upon one’s answer, perhaps the Bowdlers should be entitled to a bit more sympathy.