It’s now wait-and-see, partly because that’s just the nature of the problems, and partly because I think there is no unifying public sphere with sufficient authority at this point to settle any of it for people who are not of a particular persuasion.

Ambiguity, uncertainty and the fog-of-pandemic – the dominant themes of our time.

12 October 2021 (Milos, Greece) – In the summer of 2019 I had done one of my “self-isolation” moves, getting off the grid for almost 3 months. I had returned to Crete to continue an ongoing project my wife and I started a number of years ago: volunteer work with a sea turtle research and conservation organization based in Chania which is on a mission to protect endangered sea turtles and their natural habitats. I also just needed the silence and space for thoughts to unfurl in whatever direction, undisturbed by the “real” world.

I rediscovered my use of paper notebooks and the joy of making lists and diagrams and flow-charts (with four different colored pens!!) and some (pathetic) illustrations. I wanted to use those notebooks … automatic error-correction is never the default … and go over and over the same material, adjusting, correcting, copying out, underlining, coloring . . . the way that tactile, childish and seemingly pointless activities always seem to force you to examine things in every detail, from every available point of view.

And I began to reread Rachel Carson (the Library of America had recently issued a monster, new compendium of all her writings and my publisher consortium had sent me a paperback copy). Everybody knows Silent Spring, but it’s her books and articles about the sea (exploring the whole of ocean life from the shores to the depths) that deserve more attention. She was incredibly prescient about what was happening to the seas due to exploitation, and even more so about what she perceived was the growing “government assault on science and nature”. She wrote about our plundering of wildlands, disrupting established ecological niches, destroying life cycles.

No, she did not write about novel diseases, such as Ebola, HIV, Marburg, and SARS, or human infectious diseases having a zoonotic origin. But she wrote about how humans do not operate within their ecosystems in the same way as other species, even other top-level predators. That we don’t have “an ecological niche” but that we dominate and alter the local ecosystems. That we are part of a massive biosphere … blundering into ecosystems we are part of but destroy.

Much of it all came back to me last year during the pandemic lockdown. My media team and I (6 full-time staff with an added 6 freelancers during COVID) jumped into “everything-coronavirus” and produced 100+ articles and private client memos (many of these pieces are freely available here).

And, yes, there was a tsunami of material to read. With a high level of complexity. The unprecedented uncertainty amid the coronavirus pandemic … especially the data … had decimated our carefully laid plans and unsettled our minds at equal pace. This coronavirus, with its health, social, scientific and economic impacts, had made the content production engine of this world go into overdrive, leaving most of us struggling within an infodemic.

Also, I was venturing onto ground where I had no guarantee of safety or of academic legitimacy (a second, minor university degree in physics, of all things, but an avid reader of all-things-science my entire life) so it was not my intention to pass myself off as a scholar, nor as someone of dazzling erudition. It was enough for me to act as a messenger for those who did have the knowledge, and offer my own reflections on that knowledge. As I wrote at the time:

No doubt the old dream that once motivated Condorcet, Diderot, or D’Alembert has become unrealizable – the dream of holding the basic intelligibility of the world in one’s hand, of putting together the fragments of the shattered mirror in which we never tire of seeking the image of our humanity. But even so, I don’t think it’s completely hopeless to attempt to create a dialogue, however imperfect or incomplete, between the various branches of knowledge effecting and affecting this pandemic.

Today my team and I are onto other things but I still receive weekly updates from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

In the end I think this coronavirus has forced us (once again) to see that there really is no division between the “hard” sciences” and the “soft” sciences. Our move to take traditional disciplines and fragment them into 1,000 autonomous domains is misguided. To understand, to cope with this coronavirus and what will become the “new normal” (a very dubious term but it will need to suffice for this post) we need to deal with the complexity of this new territory.

I am still struggling with this stuff. I still have much to learn. So far all the complex/interlocking dynamics exposed show a basic absurdity at the heart of our global society. It is not a system aimed at satisfying our desires and needs, at providing humans with greater amounts of physical utility. It is instead governed by impersonal pressures to turn goods into value, to constantly make, sell, buy, and consume commodities in an endless spiral and ignoring the effect of that system on the “normal human”.

And now? There is little left to say except to see things play out. I think the basics are clear: vaccines are going to work very well, but not prevent breakthroughs completely and that Delta is very good at finding the remaining pockets of the unvaccinated. Barring a major new development, I think that’s it for the next few months, and real life will answer more of the remaining open questions.

Yes, I am in a mostly wait-and-see partly because that’s just the nature of these problems, and partly because I think there is no unifying public sphere with sufficient authority at this point to settle any of it for people who are not of a particular persuasion. Ambiguity, uncertainty and fog-of-pandemic remain the dominant themes. There is more we do not know about this virus than what we do know.

So I’ll be watching these things:

1 – Will there be a big winter wave? Maybe less likely in places with high vaccination rates, or who have already had major outbreaks.

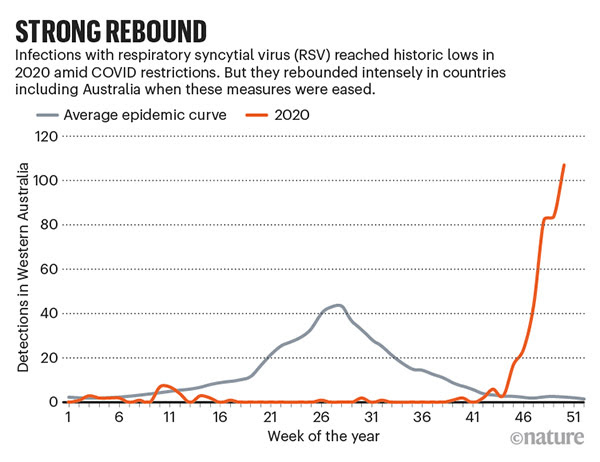

2 – What’s going to happen with flu? I’m told it’s nowhere to be seen, but never underestimate the flu. Ask Australia:

I think the COVID-19 pandemic is continuing to have unusual and unexpected effects on a number of respiratory diseases — some have been quashed, others have ploughed through and still more are rebounding off-season. These fluxes are complicating medical responses to the pandemic, but also providing scientists with an opportunity to study how these viruses spread.

3 – It’s still unclear where this disease will finally land once the first round of “most everyone has had the infection/been vaccinated” concludes, almost certainly sometime in 2022 but possibly earlier in some places. It’s hard to dismiss the fact that we now have another human coronavirus into the mix of respiratory diseases we have to deal with, but perhaps all that we have learned about respiratory diseases in general (especially aerosol transmission) and the new frontiers of vaccines and antiviral therapeutics may help balance out the harms.

As I have noted many times before, we are in an age of atomised and labyrinthine knowledge. Many of us are forced to lay claim only to competence in partial, local, limited domains. We get stuck in set affiliations, set identities, modest reason, fractal logic, and cogs in complex networks. And too many use this complexity of knowledge as an excuse for dominant stupidity.

Throughout the pandemic, there have been some things that have been confusing, but many that should not have been. I know there will be some pretty large books to be written about it all. But as I ponder storytelling and science and the public sphere I often wonder: is it because we find the ambiguous, the plot twist, the counterintuitive more interesting than the boring, basic and even obvious? Is this part of what drives this confusion?

I’m not sure because at some point we lost the plot by our own storytelling. We added complexity to things that were simple, and overly-simplified things that needed nuance. And we also got bogged down by too-much, too-clever, contrarian thinking.

We live in an inherently unstable system: everyone is connected but no one is in control. The world is always in overdrive, with a relentless acceleration in human development over the past two centuries. We are living longer, producing more, consuming more, devouring energy and space on an unprecedented scale – and generating waste and emissions in tandem. But then maybe I am just a fableist. Perhaps this pandemic was “nature’s revenge” on our voracious species.

As Gaia Vince has noted (a long-time connection of mine who I quoted throughout my COVID series):

Humans do not operate within their ecosystems in the same way as other species, even other top-level predators. We don’t have an ecological niche, but rather we dominate and alter the local—and now, global—ecosystem cumulatively to suit our lifestyles and improve our survival, including though habitat loss, introduction of invasive species, climate change, industrial-scale hunting, burning, planting, infrastructure replacement, and countless other modifications. It means that while other species do not naturally cause extinctions (except in rare circumstances, such as on islands), humans currently threaten over 1 million of the world’s 8 million species.

We are a part of the biosphere and as we blunder into ecosystems we must be mindful of the greater systems that we are all a part of. We are trapped in a spiral. We have lapsed into magical thinking, unable to navigate a web of complexity, blind to simple solutions, staring down broken systems. With devastating consequences that we are only just beginning to address.

In my wild Imaginings I see geologists from a future civilization examining the layers of rock that are in the slow process of forming today. In the same way we examine the rock strata that formed as the dinosaurs died off. That civilization will see evidence of our sudden (in geological terms) impact on the planet – including fossilised plastics and layers both of carbon, from burning carbon fuels, and of radioactive particles, from nuclear testing and explosions – just as clearly as we see evidence of the dinosaurs’ rapid demise. We can already observe our layers forming today.

I’ll end with a quote from one of my favorite books, by the evolutionary biologist E.O. Wilson, who wrote in The Social Conquest of Earth (2012):

“We have created a Star Wars civilization, with Stone Age emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology.”

As he details in his book, although kin psychology lies at the foundation of genetic ingroups, humans form factions around anything and simply being a member of a group is usually enough. This is called the “minimal group paradigm” and it is one of the most well-established findings in social psychology – research has shown that even beliefs about whether hotdogs are sandwiches can generate discrimination. Our instinct to assemble and join insular, protective groups is so ancient and powerful that it is unlikely we will ever arrest it, and despite the more sinister ramifications that result from forming coalitions, we probably wouldn’t want to even if we could. We remain in those silos and the concept of a shared society is lost.

Our modern fate – to be forever lost.