For more than a decade, Zuckerberg has worried about one thing above all else: controlling the next big tech platform. Caught between the gatekeepers of Apple and Google in mobile, he has tried mightily to regain control of his own destiny. There’s one person still standing in Facebook’s way. And that person isn’t a whistleblower.

It’s a guy that runs a tech behemoth more than twice as valuable as Facebook. Because this is a story about power.

25 October 2021 (Paris, France) – This is going to be a very Facebook-heavy week. Over the weekend and this morning newsletter writers were noting their weekend and weekly editions could have been completely filled with just Facebook links. Before I get into the story about name changes and “platformization”, just a sampling of Facebook pieces (from scores):

Inside Facebook, Jan. 6 violence fueled anger, regret over missed warning signs • Washington Post

Internal alarm, public shrugs: Facebook’s employees dissect its election role • NY Times

Facebook’s internal chat boards show politics often at centre of decision making • WSJ

What Facebook knew – and when – about how it radicalized users • NBC News

Haugen claims backed by new Facebook whistleblower filing with SEC • The Washington Post

How many users does Facebook have? The company struggles to figure it out • WSJ

Facebook launched a limited pilot of its cryptocurrency money project • Facebook

Facebook: ‘Nanotargeting’ Users Based Solely on Their Perceived Interests • Unite.AI

As I noted last week, this “teaming up” by CNN, the Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post and other outlets is unusual. It’s not often that major news organizations coordinate to sift through a large trove of leaked company documents and agree not to publish stories about them until a certain date.

But in the world of news related to Facebook, these are extraordinary times. Something similar happened in 2016 when the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists published financial leaks in an investigation called the Panama Papers, uncovering details of the global elite’s tax havens, and in 2013 after ex–National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden released top-secret documents, kicking off a storm of coverage in global newspapers about how the U.S. and other governments spy on citizens and organizations.

And Facebook’s almost programmed response? It’s only convincingly troubled by “disinformation” if it’s about itself. The usual MO of Facebook’s chiefs has been to deny they even did the thing they’re being accused of, until the position becomes untenable. At that point, they concede they did whatever it was on a very limited scale … until that position becomes untenable. Next up is accepting the scale was more widespread than initially indicated, but with the caveat that the practice has now come to an end … until that position is the latest to become untenable. Because clear evidence always comes forward that the practice never came to an end and, in fact, only became more widespread. As Guardian columnist Marina Hyde put it last last week:

We get rinsed; they repeat. Of course, many of us have long accepted that when the firm finally does cause the apocalypse, the event will be succeeded by a video of Facebook VP Nick Clegg going: “We will do better.” I am now beginning to think the event may even be preceded by a Clegg video announcing: “We will learn from this. Find out from WHAT when the darkness falls next week.”

So this week it’s Facebook’s turn to feel the Wrath of Kahn. But let’s move onto the bigger issues.

Are the problems with social media essentially familiar or novel? If you read mainstream reporting, the online malaise (especially in the U.S.) seems to fit neatly within journalism’s favorite framework: abuse of corporate power. We’re told that like Big Tobacco, Facebook concealed warnings about the harms of its product (although Big Tobacco is a very poor analogy which I’ll discuss in a separate post). Like for Standard Oil, the remedy is trust-busting.

But to others, social media is a “technological shock” that is so large that we should abandon most existing premises and theories and just try to figure out what the hell is going on. The stories we’re drawing upon to make sense of our online moment seem exhausted. They are so inadequate that we must write new ones from scratch.

And that need to write new ones comes from a long provenance. In my blog posts I often quote Philip Agre, especially his pioneering article from 1994 titled Surveillance and Capture which is about the way computing systems and networks “capture” data. I love the word “capture”, an implication of a measure of violence as these systems force their environment (us) into the modus of data-engines. He predicted that we’d see a permanent translation of the flux of life into machine readable bits and bytes. And without using the word “platform” but in every sense of the word meaning platform, he said this was all due to the growing reliance on data-driven decision systems, systems “that would need ever more behavioral data as they move into cyberphysical systems. It will completely overhaul our existing information infrastructure, and the thirst for data will have no end”.

It’s also brings up one of the things I detest about the Internet and how it has changed our thinking. It is the inexorable disappearance of retrospection and reminiscence from our digital lives. Our lives are increasingly lived in the present, completely detached even from the most recent of the pasts. And yet we have this enormous global information exchange at our disposal. So much of what we are experiencing now, often considered as “new”, has been addressed in detail in the past. Besides Agre, Nicholas Negroponte and his book “Being Digital”, originally published in January 1995, jumps to mind. His book provides a general history of several digital media technologies, many that Negroponte himself was directly involved in developing. He said “humanity is inevitably headed towards a future where everything that can will be digitalized (be it newspapers, entertainment, or sex) because we’ll get better at controlling those unwieldy atoms”. He introduced the concept of a virtual daily newspaper (“customized for an individual’s tastes”), predicted the advent of web feeds, personal web portals, “mobile communications in your pocket”, and that “touch-screen technology would become a dominant interface”.

But in a sense, this is hardly surprising: the social beast that has taken over our digital lives has to be constantly fed with the most trivial of ephemera. And so we oblige, treating it to countless status updates and zetabytes of multimedia (almost 4 thousand photos are uploaded to Facebook every second), and the latest “business news” which is really a press release or a paid ad (and rarely disclosed as such). This hunger for the present is deeply embedded in the very architecture and business models of social networking sites. Google and Facebook and Twitter and [insert your fav social media or news feed here] are not interested in what we were doing or thinking or writing 5 years ago, or 10 years ago, or 20 years ago; it’s what we are doing or thinking about right now that the systems say “we really need to know”.

Obviously Agre did not use the word in 1994 but all of his work is tracking the concept that we have been “platformed”. What sets the new digital data superstars apart from historical firms is not their market dominance; many traditional companies have reached similarly commanding market shares in the past. What’s new about these companies is that they themselves are the markets.

Platformization has become the order of the day in every domain, not just Amazon / Apple / Facebook / Google / Microsoft. Agriculture, retail trade, transportation, tourism, banking, finance, on-demand services: name it, and you can spot it. This shift has fostered monopolistic tendencies and market concentration across the economy. As Stacy Mitchell (a brilliant journalist whose focus in on concentrated economic power) said over 6 years ago in her in-depth report on Big Tech’s platform power (with a focus on Amazon’s power, scope and impact) : “we are going to have a multi-trillion-dollar monopoly/ecosystem hiding in plain sight.”

And for Mark Zuckerberg this has made all the difference.

Blame this man

Rebranding a company. We’ve seen a few biggies. When I wrote about Google’s metamorphosis into Alphabet I noted it took months, not weeks, of planning. Google had surfaced the idea at least a year in advance.

And so we hear that Facebook is considering some kind of rebranding – perhaps following Google and creating a new “Alphabet” umbrella holding company with a new name. The rationale? Allegedly Zuckerberg wants to reorient the company to the “metaverse”. So make Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp separate units in parallel to “the future stuff”. This might ring-fence “the future stuff” brand from the somewhat tarnished “Facebook stuff” (do consumers associate Waymo with Google?)

But me thinks The Zuck has gone down the metaverse rabbit hole the same way old Bill Gates did with his “Information Superhighway” way back when. Surely there is some displacement at work here. It’s more fun to talk about AR glasses than be shouted at in Congress.

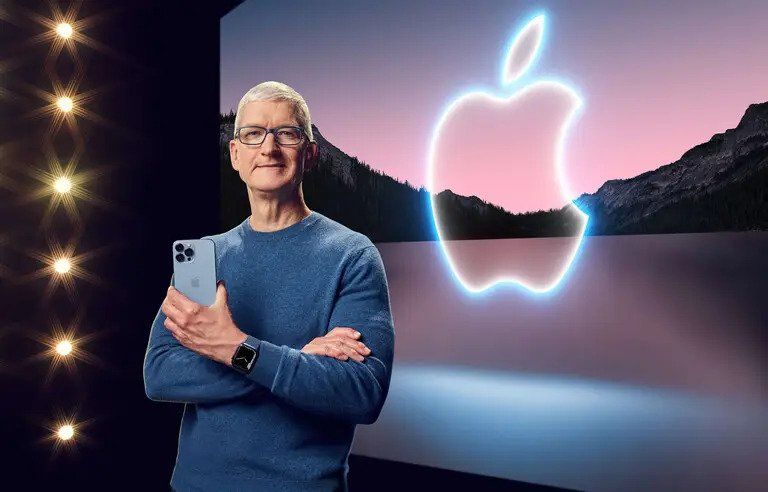

But as a CEO, I would be more likely to slam the brakes on a major rebrand in the middle of a crisis than I would be to assume such a change would solve that crisis. And so I strongly urge you to think not of Haugen, but of a different name when you’re trying to make sense of the big changes to come: Tim Cook. Because the Apple CEO is the real target of the rebrand. Let me explain.

For more than a decade, Zuckerberg has worried about one thing above all else: controlling the next big tech platform. Caught between the gatekeepers of Apple and Google in mobile, he has tried mightily to regain control of his own destiny. He pushed apps based on open web standards. He tried to build a phone. He sought to control new hardware platforms in the living room. He vowed that he wouldn’t ever again let Facebook be so dependent on platforms run by other tech companies.

And so in 2014, he paid $2 billion (yes) for a small virtual reality startup called Oculus VR. Everyone thought he was crazy. Zuckerberg, though, saw it as a form of liberation, a deal that would wean Facebook off the mobile platforms it didn’t control by helping him build one it would.

He certainly has been building away. It’s obvious how virtual and augmented reality have become an almost singular focus for him, as is clear in all of the interviews he has conducted since then. If you read these interviews closely you can feel the tension with Apple. The Zuck views the Apple threat as an existential matter, and that’s motivating him to make a shift away from the “big blue app” as a core part of Facebook’s core identity. Instead, Zuckerberg is pushing the company in a direction that is better suited to its investment in and ambitions for the “metaverse” – that fancy word for the digital realm we’re supposedly all going to play, work and communicate in through our VR and AR devices.

You need to focus on the stakes for Facebook’s metaverse moonshot when scrolling through all the analysis and commentary on VR and AR products. Its certainly possible that the metaverse will never converge or will just stay fragmented and that you will have multiple universes you will have to navigate across. A bit like the scenario we have on mobile phones today with these different kinds of app ecosystems. But Facebook’s soon-to-be-chief-technology-officer, Andrew Bosworth, reveals the tell: “We’re hoping for a more web-like outcome, to be honest with you, but it’s hard”.

Because there’s one person still standing in Facebook’s way. And that person isn’t a whistleblower. He runs a tech behemoth more than twice as valuable as Facebook, which has far more experience in hardware and is also spending gobs of money building VR and AR headsets and software, with the goal of becoming the dominant platform for the metaverse. His name is Tim Cook. Changing a company name certainly won’t win that battle. But it is Facebook attempt to shift its corporate culture and focus so that it has a better chance for success. Get out the

Because this battle is formidable. As I noted last week in my discussion of Apple’s disruption of the microprocessor market (a classic case of Clayton Christensen’s disruptive innovation framework), the big point is that across phone, tablet, TV, watch, speaker, laptop, and desktop Tim Cook has created a platform of capabilities that are unmatched even in one device group, let alone the whole spectrum. It is an unprecedented situation. Apple has developed a whole family of operating systems. These are not just related, but vastly similar enabling a huge ecosystem opportunity. THIS was Microsoft’s vision going back to early 1990s. THIS is now Mark Zuckerberg’s vision.

And it brings us to the obvious.

Technology companies are shaping the global environment in which governments operate. Political scientists rely on a wide array of terms to classify governments: there are “democracies,” “autocracies,” and “hybrid regimes,” which combine elements of both. But they have no such tools for understanding Big Tech. These companies exercise a form of sovereignty over a rapidly expanding realm that extends (somewhat) beyond the reach of regulators: digital space. They maintain foreign relations and answer to constituencies, including shareholders, employees, users, and advertisers.

This is an enormous topic, far beyond the immediate scope of this specific post. I will expand it in a subsequent musing. But just one example:

After rioters stormed the U.S. Capitol on January 6th, some of the United States’ most powerful institutions sprang into action to punish the leaders of the failed insurrection.

But they weren’t the ones you expected. Facebook and Twitter suspended the accounts of Donald Trump for posts praising the rioters. Amazon, Apple, and Google effectively banished Parler, an alternative to Twitter that Trump’s supporters had used to encourage and coordinate the attack, by blocking its access to Web-hosting services and app stores. Major financial service apps, such as PayPal and Stripe, stopped processing payments for the Trump campaign and for accounts that had funded travel expenses to Washington, D.C., for Trump’s supporters.

The speed of these technology companies’ reactions stands in stark contrast to the (continuing) feeble response from the United States’ governing institutions. Congress still has not censured Trump for his role in the storming of the Capitol. Its efforts to establish a bipartisan, 9/11-style commission failed amid Republican opposition. Law enforcement agencies have been able to arrest some individual rioters – but in many cases only by tracking clues they left on social media about their participation in the fiasco.

Side note: how well planned was it? Over this past weekend Rolling Stone published its report on how protest organizers said they participated in “dozens of planning meetings” with members of Congress and White House Staff.

States have been the primary actors in global affairs for nearly 400 years. That is starting to change, as a handful of large technology companies rival them for geopolitical influence. The aftermath of the January 6th riot serves as the latest proof that Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Twitter are no longer merely large companies; they have taken control of aspects of society, the economy, and national security that were long the exclusive preserve of the state. The same goes for Chinese technology companies, such as Alibaba, ByteDance, and Tencent. Nonstate actors are increasingly shaping geopolitics, with technology companies in the lead.

And although Europe wants to play, its companies do not have the size or geopolitical influence to compete with their American and Chinese counterparts. It thinks it can “regulate” these behemoths. I’ve written numerous pieces on why the GDPR is pointless, and by year end I hope to consolidate all of them into a monograph.

And, yes, U.S. regulators are just as clueless. Last week the U.S. DoJ published a un-redacted version of last year’s antitrust complaint against Google. My main impression after reading the complaint is how complex and poorly understood adtech is. I mean, for the DoJ lawyers not understand the “data box” … yikes! More to come.

Most of the analysis of the Western “technological shock” is stuck in a statist paradigm. It depicts technology companies as mere elements in a conflict between and among hostile governments. Mere foot soldiers, if you will, of governments. But technology companies are not mere tools under the control of governments. None of their actions in the immediate aftermath of the Capitol insurrection, for instance, came at the behest of the government or law enforcement. These were private decisions made by for-profit companies exercising power over code, servers, and regulations under their control.

These companies are increasingly shaping the global environment in which we all operate. They have huge influence over the technologies and services that will drive the next industrial revolution, determine how economic power (even and military power) is projected, shape the future of work, and redefine our social contracts.

The implications of this fact bear on virtually all aspects of civic, economic, and private life. For a new generation of entrepreneurs, Amazon’s marketplace and Web-hosting services, Apple’s app store, Facebook’s ad-targeting tools, and Google’s search engine have become indispensable for launching a successful business. Big Tech is even transforming human relationships. In their private lives, people increasingly connect with one another through algorithms.

Technology companies are not just exercising a form of sovereignty over how citizens behave on digital platforms; they are also shaping behaviors and interactions. The little red Facebook notifications deliver dopamine hits to your brain, Google’s artificial intelligence algorithms complete sentences while you type, and Amazon’s methods of selecting which products pop up at the top of your search screen affect what you buy. In these ways, technology firms are guiding how people spend their time, what professional and social opportunities they pursue, and, ultimately, what they think. This power will grow as social, economic, and political institutions continue to shift from the physical world to digital space.

These companies are increasingly providing a full spectrum of both the digital and the real-world products that are required to run a modern society. Although private companies have long played a role in delivering basic needs, from medicine to energy, today’s rapidly digitizing economy depends on a more complex array of goods, services, and information flows. Currently, just four companies – Alibaba, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft – meet the bulk of the world’s demand for cloud services, the essential computing infrastructure that has kept people working and children learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. The future competitiveness of traditional industries will depend on how effectively they seize new opportunities created by 5G networks, AI, and massive Internet-of-Things deployments. Internet companies and financial service providers already depend heavily on the infrastructure provided by these cloud leaders. Soon, growing numbers of cars, assembly lines, and cities will, too.

And national security, a role that has traditionally been reserved for governments and the defense contractors they hire? When Russian hackers breached U.S. government agencies and private companies last year, it was Microsoft, not the National Security Agency or U.S. Cyber Command, that first discovered and cut off the intruders.

This is why the machinations of Apple and Facebook mean so much. It’s more than technology stacks and a “metaverse”. It goes to the very nature of society stacks.

And before you jump in, yes: Big Tech’s eclipse of the nation-state is not inevitable. Governments are taking steps/will take steps to tame an unruly digital sphere (China) and the West will continue to do what it can (the EU’s attempts to regulate personal data and AI, and the U.S. going after the digital gatekeepers via numerous antitrust bills). Yes, the technology industry is facing a political and regulatory backlash on multiple fronts. Technology firms cannot decouple themselves completely from physical space. Those virtual worlds sit in data centers which are all housed somewhere.

I’ll leave in there. I’ve run too long as it is. But one last point.

As technology has gown more sophisticated, states and regulators have found themselves increasingly constrained by outdated laws and limited capacity. Digital space is ever growing. Facebook now counts nearly three billion monthly active users. Google reports that over one billion hours of video are consumed on YouTube, its video-streaming platform, each day. Over 64 billion terabytes of digital information was created and stored in 2020, enough to fill some 500 billion smartphones.

In its next phase, this “datasphere” will see cars, factories, and entire cities wired with Internet-connected sensors trading data. As this realm grows, the ability to control it will slip further beyond the reach of states. And because technology companies provide important digital and real-world goods and services, states that cannot provide those things risk shooting themselves in the foot if their draconian measures lead companies to stop their operations.