The global shortage of microchips remains one of the most significant technology stories in the world

14 September 2021 (Milos, Greece) – The global shortage of microchips remains one of the most significant technology stories in the world. The world’s leading suppliers of semiconductors are pushing to overcome the prolonged chip shortage that has hampered production of everything from home appliances to PCs to autos. Chip makers are trying to eke out more supply through changes to manufacturing processes and by opening up spare capacity to rivals, auditing customer orders to prevent hoarding and swapping over production lines. The bad news is, there are no quick fixes, and shortages will likely continue into next year, according to most industry’s executives. Jay Greenberg has provided the most detailed overviews on how this all happened.

Despite the intense amount of coverage and debate, I continue to learn more and more about the complexity of manufacturing chips every week. The more I learn about the process, the more intriguing and layered it becomes. And having been weaned on Jay Greenberg’s work plus Donna Meadows’ Thinking in Systems plus the in-depth pieces by Jordon Nel is has been so much easier.

To that end, I was still stunned by the insights of Dr Willy Shih of Harvard Business School:

“When you think about a process that has 700 steps, you need to execute each step with a very high yield. Because if you had 99 per cent yield for the first step and 99 per cent for the second step, you and I would think, “Wow, that’s pretty good, right?” But if you take 99 per cent yield through 700 steps, by the time you’re done, you’ll get nothing at the end which is workable”.

This extraordinarily complicated process has given rise to several smaller companies who have emerged as veritable kingmakers during the global shortage. These companies manufacture substrates that connect chips to the circuit boards that keep them in place in computers and other devices.

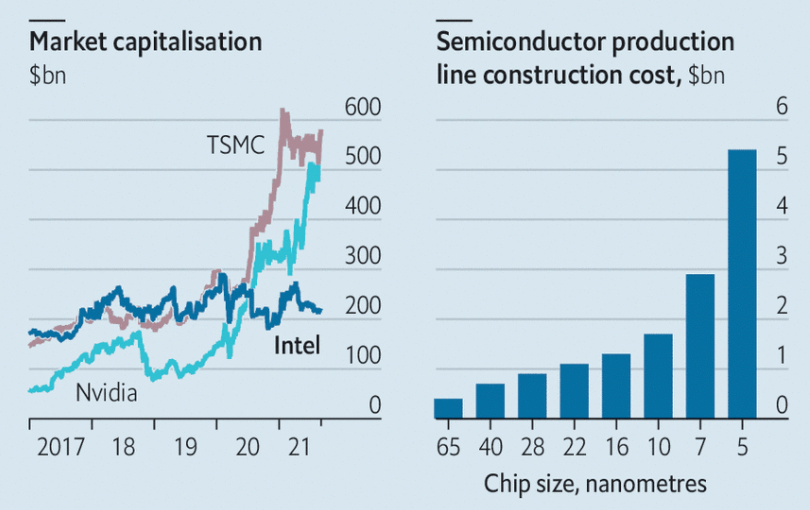

This sector of the manufacturing process used to be a backwater, but now substrate manufacturers can almost name their price. Investigating how elaborate chip manufacturing and supply chains have become reveals just how deep a crisis we face. It’s going to be a long ride until the shortages end and in the short term, prices are going to rise. And note how Intel is trying to reinvent itself and get back to the forefront of chipmaking.

SOURCE: The Economist

For those of you who subscribe to my weekend “Brain Droppings” column where I try to do a deep-dive into one subject, this is why I expect the chip shortage to contribute to engineers reducing the number of physical components used and turning instead to software to handle functions that had historically been done in hardware. The shortages tied to the pandemic are an accelerator for this shift, but it has been happening for years as the industry adjusts to the end of “Moore’s Law” and the ability to eke out more performance at lower costs.

As I have noted and as have the pundits I mentioned above have noted, electrification of vehicles and the internet of things were two driving forces behind the resurgence of chip sales heading into 2020. That’s because electric cars require a lot more computer and chip-based components than those powered by gas, while the IoT is adding silicon to devices that historically haven’t required (or really needed) chips. In 2019 (the last on-site event I attended) I was at the Munich, Germany tech innovation show and I saw the prototype for a lightbulb … a light bulb! … with 12 components.

Plus, consumer demand for smarter products ramped up. Many people felt compelled to invest in new computer gear, lights, and cameras for their Zoom setups at home, and some even bought new homes that they wanted to make smart. As for the automotive companies, they quickly realized that demand wasn’t dropping, so they tried to ramp up production. But without chips – the underlying building block of any “smart” product – those companies were forced to wait, which explains why it’s a great time to sell your used vehicle and why you can’t get a rental car right now.

And there is a third shift happening … which really needs one of my TL;DR posts 🙂 … that will change the market for both chips and hardware going forward. Costs are rising. Labor costs are creeping higher because it costs more to protect workers from COVID. Plus, in many manufacturing industries, there aren’t a lot of new workers coming in to replace those that are not returning. Meanwhile, material costs are rising because labor and shipping costs are rising.

For decades the industry has been a slave to “Moore’s Law”, that law that says chip makers could double the number of transistors on a chip (transistors dictate performance) every 18 months to two years. “Moore’s Law” meant that every two years or so a new generation of computers got more powerful. It led to falling prices for memory, CPUs, and even basic GPUs.

But it’s becoming harder to eke out those performance gains. Plus, there are many products, such as power management chips or timing chips, that don’t benefit from “Moore’s Law”. So as the fundamentals of chip economics change, suppliers will have to adapt. I expect (have seen) chip companies reassess their product lines and eliminate older ones with low margins. At the same time, many engineers and designers see shortages in certain parts and so are designing them out of their products entirely. They may choose to integrate more functions into a newer, specialty chip or handle something in software that used to depend on hardware. Chipmakers that can build these integrations and this software will have an advantage.

It is why we are seeing creeping opportunities for startups that want to tackle this problem as well – where the serious VC money is going. I have been a limited partner in a VC firm for 4 decades and now I see this surge in meeting notices with startups and engineers who are trying to consolidate more hardware into a single system on a chip or do away with it altogether.

Yep. These are tough times for chip companies and for the growing number of industries that rely on their wares. But that pressure usually leads to real innovation, which is exactly what we need right now.