China has reached its true Sputnik moment – and a new national industrial policy is born

3 August 2021 – Since the early days of the Cold War, the United States has led the world in technology. Over the course of the so-called American century, the country conquered space, spearheaded the Internet, and brought the world the iPhone.

In recent years, however, China has undertaken an impressive effort to claim the mantle of technological leadership, investing hundreds of billions of dollars in robotics, artificial intelligence, microelectronics, green energy, and much more. Washington has tended to view Beijing’s massive technology investments primarily in military terms, but defense capabilities are merely one aspect of great-power competition today – little more than table stakes. Beijing is playing a more sophisticated game, using technological innovation as a way of advancing its goals without having to resort to war. Chinese companies are selling 5G wireless infrastructure around the world, harnessing synthetic biology to bolster food supplies, and racing to build smaller and faster microchips, all in a bid to grow China’s power.

In the face of China’s technological drive, U.S. policymakers have called for greater government action to protect the United States’ lead. Much of the conventional wisdom is sensible: boost R & D spending, ease visa restrictions and develop more domestic talent, and build new partnerships with industry at home and with friends and allies abroad. But the real problem for the United States is much deeper: a flawed understanding of which technologies matter and of how to foster their development. As national security assumes new dimensions and great-power competition moves into different domains, the government’s thinking and policies have not kept pace.

I’ll address all of these points in a longer post this fall after my break. But right now I want to address a bigger point that I think most people are missing. By seemingly dismantling critical parts of its technology sector, China is redefining what progress means. That’s the central argument being put out by Chris Darby, Noah Smith, Dan Wang and many others. It’s impossible to navigate the complex relationships between business and the Chinese state but on the outside it looks like China is “smashing” its tech sector. Why would it do such a thing? Simple:

Beijing has determined that too many resources were being poured into consumer-facing tech so the decision was made to pivot those resources back into military technology.

It’s way too much to cover in a short blog post like this but I’ll unpack the basic tenets.

As Noah Smith details in a blog post, those who pay attention to business news have probably noted an interesting and curious phenomenon over the past few months:

China is smashing its internet companies. It started — or at least, most people in the U.S. started noticing it — when the government effectively canceled the IPO of Ant Financial, then dismantled the company. Jack Ma, the founder of Ant and of e-commerce giant Alibaba, was summoned to a meeting with the government and then disappeared for weeks. The government then levied a multi-billion dollar antitrust fine against Alibaba (which is sometimes compared to Amazon), deleted its popular web browser from app stores, and took a bunch of other actions against it. The value of Ma’s business empire has collapsed.

But Ma was only the most prominent target. The government is also going after other fintech companies, including those owned by Didi (China’s Uber) and Tencent (China’s biggest social media company). As Didi prepared to IPO in the U.S., Chinese regulators announced they were reviewing the company on “national security grounds”, and are now levying various penalties against it. The government has also embarked on an “antitrust” push, fining Tencent and Baidu — two other top Chinese internet companies — for various past deals. Leaders of top tech companies (also including ByteDance, the company that owns TikTok) were summoned before regulators and presumably berated. Various Chinese tech companies are now undergoing “rectification”.

For those outside China’s byzantine, opaque nexus of party, government, and big business, it’s very difficult to figure out what’s going on. Just who is ordering these actions is not clear, or what the ultimate result of the crackdown will be. That makes it very hard to figure out why it’s happening. Some observers see this as an antitrust campaign, similar to the ones going on in the U.S. or the EU. China’s leaders famously want to prevent the emergence of alternative centers of power, but is the West so different in this regard? One of the driving motivations behind the new antitrust movement in the U.S. is to curb the political power of Big Tech companies specifically; if you wanted to, you might see the Chinese tech crackdown as simply a Neo-Brandeisian movement on steroids.

But step back a bit and look at “The Big Picture”. The breadth of the Chinese crackdown suggests a major difference. The U.S. has slapped down a few of its corporate giants before — Microsoft, AT&T, Standard Oil — but ultimately it didn’t crush the industries these companies were a part of. We’re unlikely to see major action against all the U.S. internet companies at once, and broad EU action will likely take the form of new rules rather than a sweeping crackdown. Noah:

China’s attack on its tech companies, in contrast, seems far more comprehensive — it’s not just attacking the biggest internet companies, it’s attacking the entire sector. An important piece of evidence here is that China also appears to be reducing venture funding. If you want more competition you don’t squash new entrants. For whatever reason, China is suddenly not a fan of the industry we call “tech”.

This is strange because for years, it was conventional wisdom in the Western media that having a “tech” sector was crucial to innovation and growth etc. In fact, for many years American pundits argued that China’s economy would be held back by the government’s insistence on control of information, because it would make it impossible for China to build a world-class tech sector. Then China did build a world-class tech sector anyway, and now it’s willfully smashing the world-class tech sector it built. So much for U.S.-style “innovation”.

But notice that China isn’t cracking down on all of its technology companies. As Chris Darby has noted:

Huawei, for example, still seems to enjoy the government’s full backing. The government is going hell-bent-for-leather to try to create a world-class domestic semiconductor industry, throwing huge amounts of money at even the most speculative startups. And it’s still spending heavily on A.I. It’s not technology that China is smashing — it’s the consumer-facing internet software companies that Americans tend to label “tech”.

Why do Americans equate “tech” with companies like Google, Amazon, and Facebook, anyway? Noah:

One reason is that the consumer internet industry is something America is really good at — unlike its electronics hardware industries, consumer software is something that hard-driving Asian competitors haven’t yet been able to beat the U.S. at. Another reason is that software companies make a lot of profit — Facebook made over $18 billion in 2020, three times Micron or Honeywell and six times Cisco. It just announced another blowout 2nd quarter for 2021. With their low overhead, network effects, troves of intellectual property, strong brand value, and differentiated products, successful software companies naturally tend to generate high margins. That’s true for smaller software companies as well as big ones. And since in America we often tend to equate profit with value, this means we think of the consumer-facing software industry as being our industrial champion, generating a huge amount of economic value for our nation.

China simply see things differently. The Chinese government has decided that the profits of companies like Alibaba and Tencent come more from rents than from actual value added — that they’re simply squatting on unproductive digital land, by exploiting first-mover advantage to capture strong network effects, or that the IP system is biased to favor these companies, or something like that. There are certainly those in America who believe that Facebook and Google produce little of value relative to the profit they rake in; maybe China’s leaders, for reasons that will remain forever opaque to us, have simply reached the same conclusion.

But there is something much bigger going on here. If you’re interested in China and its economy (which I am because it impacts my work in the mobile technology industry), one analyst everybody reads is GaveKal Dragonomics’ Dan Wang. In a recent post he noted:

I find it bizarre that the world has decided that consumer internet is the highest form of technology. It’s not obvious to me that apps like WeChat, Facebook, or Snap are doing the most important work pushing forward our technologically-accelerating civilization. To me, it’s entirely plausible that Facebook and Tencent might be net-negative for technological developments. The apps they develop offer fun, productivity-dragging distractions; and the companies pull smart kids from R&D-intensive fields like materials science or semiconductor manufacturing, into ad optimization and game development.

The internet companies in San Francisco and Beijing are highly skilled at business model innovation and leveraging network effects, not necessarily R&D and the creation of new IP. I wish we would drop the notion that China is leading in technology because it has a vibrant consumer internet. A large population of people who play games, buy household goods online, and order food delivery does not make a country a technological or scientific leader. These are fine companies, but in my view, the milestones of our technological civilization ought to be found in scientific and industrial achievements instead.

As Chris Darby and Noah Smith have noted, Dan’s job is to keep his ear to the ground, figure out what the movers and shakers in China think, and relay those thoughts to us. So when he started talking about the idea that consumer internet tech isn’t real “tech”, everybody immediately wondered if China’s leaders were thinking along the same lines. Dan subsequently wrote:

It’s become apparent in the last few months that the Chinese leadership has moved towards the view that hard tech is more valuable than products that take us more deeply into the digital world. Xi declared this year that while digitization is important, “we must recognize the fundamental importance of the real economy… and never deindustrialize.” This expression preceded the passage of securities and antitrust regulations, thus also pummeling finance, which along with tech make up the most glamorous sectors today.

In other words, the crackdown on China’s internet industry seems to be part of the country’s emerging national industrial policy, something Wang goes into in great details in this article in this month’s Foreign Affairs magazine (another magazine you should read). Instead of simply letting local governments throw resources at whatever they think will produce rapid growth (the strategy in the 90s and early 00s), China’s top leaders are now trying to direct the country’s industrial mix toward what they think will serve the nation as a whole.

And what do they think will serve the nation as a whole? Power. Geopolitical and military power for the People’s Republic of China, relative to its rival nations. Noah Smith back into this:

If you’re going to fight a cold war or a hot war against the U.S. or Japan or India or whoever, you need a bunch of military hardware. That means you need materials, engines, fuel, engineering and design, and so on. You also need chips to run that hardware, because military tech is increasingly software-driven. And of course you need firmware as well. You’ll also need surveillance capability, for keeping an eye on your opponents, for any attempts you make to destabilize them, and for maintaining social control in case they try to destabilize you.

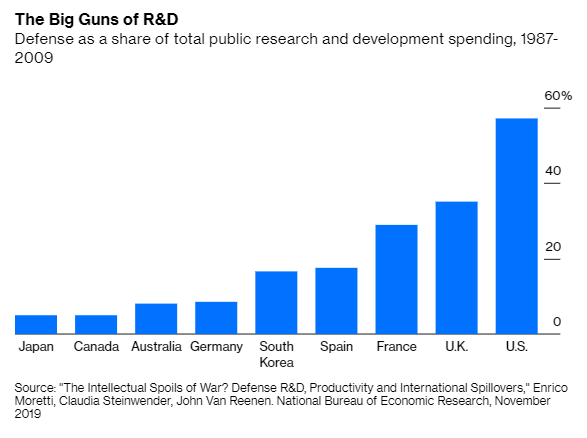

It’s easy for Americans to forget this now, but there was a time when “ability to win wars” was the driving goal of technological innovation. The NDRC and the OSRD were the driving force behind government sponsorship of research and technology in World War 2, and the NSF and DARPA grew out of this tradition. Defense spending has traditionally been a huge component of government research-spending in the U.S., and many of America’s most successful private-sector tech industries are in some way spinoffs of those defense-related efforts (see following chart):

But, alas, the U.S. got fat and lazy. After the Cold War, its priorities shifted from survival to enjoyment. Technologies like Facebook and Amazon.com, which are fundamentally about leisure and consumption, went from being fun and profitable spinoffs of defense efforts to the center of what Americans thought of as “tech”.

Noah again:

But China never really shifted out of survival mode. Yes, China’s leaders embraced economic growth, but that growth has always been toward the telos of comprehensive national power. China’s young people may be increasingly ready to cash out and have some fun, but the leadership is just not there yet. They’ve got bigger fish to fry — they have to avenge the “Century of Humiliation” and claim China’s rightful place in the sun … and yadda yadda yadda.

And so when China’s leaders look at what kind of technologies they want the country’s engineers and entrepreneurs to be spending their effort on, they probably don’t want them spending that effort on stuff that’s just for fun and convenience. They probably took a look at their consumer internet sector and decided that the link between that sector and geopolitical power had simply become too tenuous to keep throwing capital and high-skilled labor at it. And so, in classic CCP fashion, it was time to smash.

And so China reached it’s true Sputnik moment – when it realized it could not count on the United States to supply its technology and that it must cultivate domestic alternatives. And that it was going in the wrong direction. Washington bristled at Beijing’s ambitions for semiconductor self-sufficiency and then proceeded to punish Chinese companies naive enough to depend on American technologies. U.S. companies are now facing uncomfortable questions on whether they can be counted on to be reliable suppliers. For all the complaints about Xi’s efforts to drive “offensive decoupling,” it is the United States, not China, that is forcing Chinese firms to abandon American products – and now these companies are pursuing domestic self-sufficiency with a vengeance.

Is all of this enough to make Chinese industrial policy work this time around? It is likely that in a decade, China will have made greater technological advancements under the U.S. export-control regime than it would have had the United States not forced China’s leading companies to buy from weak domestic firms. Had the United States implemented necessary but measured reforms—strengthening the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States and prosecuting intellectual property theft—and stopped there, “Made in China 2025” would have likely played out in the usual way, with inefficient state-owned enterprises and government ministries taking the lead rather than innovative tech firms. But as Nick Devlan, a China watcher, notes:

But this time is different. True, China has big technological hurdles to overcome, including weak basic research, ambiguous intellectual property protections, and excessive bureaucratic meddling. Yet the United States cannot assume that China’s leading firms will stay down forever: companies are rushing to fill the demand that U.S. firms can no longer supply. Chinese firms have to reinvent only certain wheels, with many simply working to recreate technologies that already exist. And no U.S. restriction can change the fact that China is an enormous market loaded with entrepreneurial talent and technical expertise.

The ripple effects of Chinese technological success will be felt beyond China. For one thing, they will shape American politics. A Beijing less dependent on U.S. products will feel less apprehensive about retaliating against American firms, giving it license to respond to perceived affronts. For another thing, as Sarah Sewell notes in another article in this month’s Foreign Affairs, technological dominance will shift the Chinese leadership’s calculations on Taiwan:

Beijing knows that any armed invasion of the island would prompt U.S. sanctions that could inflict great pain on the Chinese economy. Greater self-reliance would deflate the threat of those sanctions and remove a deterrent against military action.

The economic consequences of Chinese technological dominance on the United States would be no less significant. For the most part, U.S. technology firms have stayed a few steps ahead of their Chinese competition. But they might fall back as their sales dip and as Beijing launches a more powerful drive to replace them. If China comes to dominate semiconductor production in the way it has dominated solar panels, then the United States will have lost its last crown jewel in manufacturing as the products become commoditized and profits disappear.

But, it’s nuanced. At this point, no effort on behalf of the U.S. government can deter China’s state from its end goal of industrial self-sufficiency. But Washington can still change the calculations of private Chinese tech companies. Many of these businesses would rather not have to reinvent their tools and find new suppliers and would likely stick with U.S. technologies if given the chance.

But slowly, ever so slowly, U.S. analysts are saying “Washington should know better than to fuel its greatest competitor”. They realize that what is at stake is the future global center of technological innovation. And China is making it very clear that the “Pacific century” is indeed the path forward.

One Reply to “China points the way to a technology solution: just smash the sector to bits”