There are enormous tasks that lie ahead. But because we have been so dumbed down and want relief from this horrid year, we are … once again … ignoring the science.

23 November 2020 (Athens, Greece) – For all that scientists have done to tame the biological world, there are still things that lie outside the realm of human knowledge. The coronavirus was one such alarming reminder, when it emerged with murky origins in late 2019 and found naive, unwitting hosts in the human body. Even as science began to unravel many of the virus’s mysteries – how it spreads, how it tricks its way into cells, how it kills – a fundamental unknown about vaccines hung over the pandemic and our collective human fate: vaccines can stop many, but not all, viruses. Could they stop this one?

Well, it’s complicated. Pfizer and Moderna have separately released preliminary data that suggest their vaccines are both more than 90 percent effective, far more than many scientists expected. Neither company has publicly shared the full scope of their data … and that’s a big issue as I note below … but independent clinical-trial monitoring boards have reviewed the results to the point they meet with threshold of the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) so that the FDA will soon scrutinize the vaccines for emergency use authorization.

And as I write this, AstraZeneca and Oxford University have announced their vaccine is “highly effective”, up to 90 percent effective.

It is remarkable. I do admire the disciplines that got us three working vaccines in about 11 months from sequencing what was then 2019-nCov.

But there are enormous tasks that lie ahead – manufacturing vaccines at scale, distributing them via a cold or even ultracold chain, and persuading wary Americans to take them – which are not trivial. These are all within the realm of human knowledge.

And because we have been so dumbed down and want relief from this horrid year, we are … once again … ignoring the science.

Just because two vaccines were recently shown to be 90% effective does not mean the end of the pandemic is in sight. Far from it. In the U.S., half of the American public polled don’t trust COVID vaccines. As S. Churchill (a risk forensics expert and Global Risk Mitigation Specialist) puts it so succinctly:

• Some believe that vaccines are dangerous and a smaller cohort do not believe the pandemic is a real. Another subset have little faith in government. They view objecting to vaccination campaign mandates as an intrinsic right.

• Worse, young adults are especially prone to asymptomatic infection. This age group is vulnerable to peer pressure. They may be among the least willing to undergo vaccination.

• And does the vaccine prevent symptoms? Does it keep the vaccinated public from spreading the virus? How long will immunity last? How well does it protect the elderly and those with a weaker response to the flu vaccine?

• And will these new mRNA vaccines induce short-duration resistance, allowing possibility of repeated reinfection risk, as is the case for natural immunity against a respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)? A clue for you: RSV and COVID19 viruses and nanoparticles catalyze aggregation of sticky molecules from bodily fluids before invading cells, enabling immune evasion and increased disease severity.

mRNA vaccines offer a clever shortcut. We humans don’t need to intellectually work out how to make viruses; our bodies are already very, very good at incubating them. When the coronavirus infects us, it hijacks our cellular machinery, turning our cells into miniature factories that churn out infectious viruses. The mRNA vaccine makes this vulnerability into a strength. What if we can trick our own cells into making just one individually harmless, though very recognizable, viral protein? The coronavirus’s spike protein fits this description, and the instructions for making it can be encoded into genetic material called mRNA.

But speak with any epidemiologist and therein lies the danger. The next few months will be a test of one potential downside of mRNA vaccines: their extreme fragility. mRNA is an inherently unstable molecule, which is why it needs that protective bubble of fat, called a lipid nanoparticle. But the lipid nanoparticle itself is exquisitely sensitive to temperature. For longer-term storage, Pfizer/BioNTech’s vaccine has to be stored at –70 degrees Celsius and Moderna’s at –20 Celsius, though they can be kept at higher temperatures for a shorter amount of time. Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna have said they can collectively supply enough doses for 22.5 million people in the United States by the end of the year.

Judging by headlines … and even the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna press releases … “it’s game over for coronavirus”. It seemed the end of the pandemic had been spied over the horizon.

The small print, though, gives pause for thought: the results were revealed in a Pfizer press release, not a published scientific paper; it is unknown how long immunity lasts or whether the symptoms of those who did contract Covid-19 were mild or severe; it has not been revealed how well the vaccine, called BNT162b2, worked in older age groups – the key targets of any nationwide vaccination strategy. Neither do we know whether the vaccine curbs transmission as well as easing disease symptoms.

There were also logistical issues. The formulation needs ultra-cold temperatures to stay stable and is packaged “as if James Bond might courier it back to London for M16: special suitcases, lined with dry ice and GPS trackers, are each capable of storing 5,000 doses at -70˚C for ten days, as long as they are not opened more than four times” (Cliff Packard in The Guardian). Even Professor Sahin (who co-founded BioNTech in 2008 and has served as Chief Executive Officer since that time) admitted in a press briefing the logistical challenges meant it would be summer 2021 before the pandemic started to recede.

The Pfizer good news was followed by a booster from Moderna, which claimed its vaccine was nearly 95 per cent effective. The U.S. company’s data showed it appeared to work in older people and to stop severe disease. The Moderna vaccine, called mRNA-1273, has the edge on Pfizer in terms of practicality: it can be stored for six months at -20˚C and, once thawed, for a month in a fridge.

These encouraging results, while preliminary, justify restrained optimism. The gamble by many vaccine teams, including Pfizer and Moderna, to build their vaccines by copying the spike protein – the portion of Covid-19 that most readily presents itself to the immune system – is apparently paying off (the Russian Sputnik-V vaccine is also claimed to be more than 90 per cent effective, but details are scant).

Yes, overall, it is good news. As the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center noted it is positive news because we now know that spike protein vaccines probably work against coronavirus. Over the weekend, CNN International had an interview with Dr Saul Faust (professor of paediatric immunology and infectious diseases at the UK’s Southampton University) who directs the Southampton’s National Institute of Health Research Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility COVID-19 vaccine project and he also saw the news as very positive. The UK project has just begun a trial of the Janssen Covid-19 vaccine (also known as the Johnson & Johnson vaccine).

I have 20+ doctors and epidemiologists assisting me as resources for my COVOD-19 series. One works at the Centre for Vaccinology in Ghent, Belgium and they are vaccinating test subjects with the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. She keeps me in the loop.

Pfizer and Moderna will now apply in the U.S. for “emergency use authorisation” so its vaccine can be rolled out to high-risk groups. But the arrival of the first official vaccine may bring new headaches. Other clinical trials, which could yield excellent second, third, fourth and even fifth Covid vaccines, will not have finished.

That could throw the ongoing trials into ethical doubt. I did not find a U.S. source but the UK-based Journal of Medical Ethics puts it like this and it certainly applies to the U.S. trials:

“There are compelling reasons why it would be unethical to trial a novel vaccine when an effective product already exists. Volunteers on other clinical trials would be entitled to pull out to receive a licensed vaccine. The possibility of other vaccine trials collapsing would be a grave setback. According to Kate Bingham, head of the UK government’s vaccine task force: ‘If we don’t continue all the trials, we won’t know if we have better vaccines coming behind the front-runners.’ Bingham also added that nobody has seen the fine detail on the Pfizer/BioNTech results yet.”

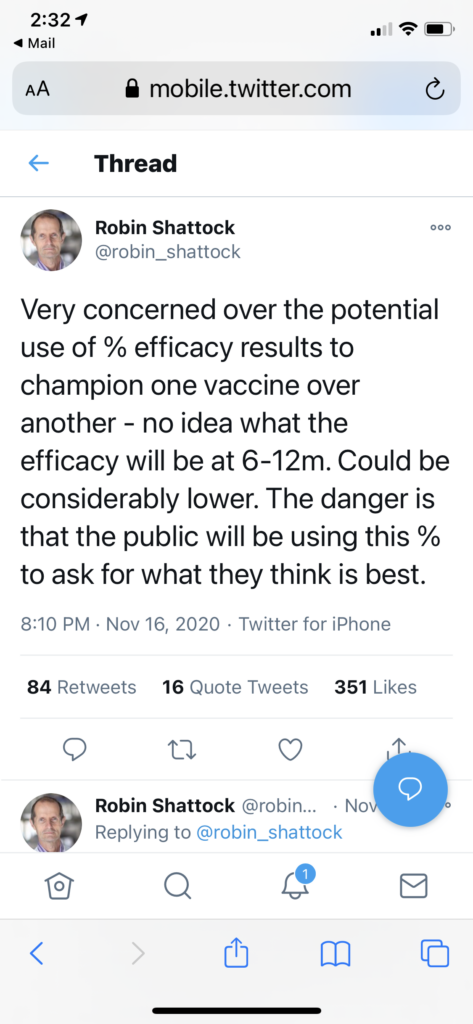

Some of the immunity snapshots revealed in the preliminary data were taken just weeks after trial volunteers received boosters. Professor Robin Shattock, who is leading a Covid vaccine project at Imperial College London, warned in a tweet that the observed immunity might not endure:

There are also practical imperatives for keeping the vaccine race alive despite Pfizer and Moderna’s early dominance: the bid to defeat Covid-19 is not a national effort but a global one demanding billions of doses – beyond the scope of any one manufacturer. The world needs not only Vaccine One, but also Two, Three and Four – as many as science can throw out.

Advanced clinical trials for potential COVID vaccines all run along the same lines. First, tens of thousands of people are divided into two groups: a test group and a control group. The test group receives the experimental coronavirus vaccine; the control group is injected with a placebo or dummy formulation that offers no protection against Covid-19 (the Oxford trials use a meningitis vaccine as the control; some use saline solution. There is a good summary of the Oxford trials here).

The recipient does not know whether she has received the coronavirus vaccine or the control one – and neither does the person who administered it. This “blinding” is important: a person who knows they might be protected might behave more recklessly. Then the scientists sit back and wait for participants to get COVID-19 in the real world. In the Pfizer/BioNTech study, 94 people out of more than 43,000 participants developed symptomatic infections. At that point, the study was “unblinded” to find out how the infections were spread across the two groups. The majority of infections happened in the control group that received the dummy, suggesting the coronavirus vaccine was indeed protecting the test group.

Trials vary in how quickly they reach the numbers that allow these statistically meaningful early readouts, depending in part on how much virus is circulating. It can take weeks, sometimes months, to accumulate the necessary numbers. The wait can be longer if the dosing regime requires a booster. The two doses of the Pfizer vaccine are 21 days apart; the Janssen vaccine requires a gap of 57 days between injections. The Moderna doses are a month apart.

The prospect of volunteers dropping out of ongoing trials if they are summoned in spring or early summer to be given an approved vaccine is, according to Professor Faust:

” … a really important question. Will it affect the trials? We hope not but of course it could. Participants in the Novovax trial have already started asking us about this when they come for their appointments.”

He is heartened that they haven’t cancelled, instead quizzing researchers about the Pfizer news. When people hear why it’s important to science for vaccine trials to continue regardless of developments elsewhere, he says, they have been persuaded to continue.

One book I urge you to read is Mark Honigsbaum’s The Pandemic Century which puts all of the various issues and aspects of vaccine development in perspective. He is actually a vaccine test volunteer, having joined the Novovax vaccine trial. In a BBC interview he said:

“I immediately wanted to do it, mostly out of curiosity, if I’m honest, and because it might be useful when I write about it. I think people like me, who promote vaccines as safe and important medical interventions, should be prepared to be guinea pigs for the sake of the wider community. I also have an 88-year-old mother who I see regularly, with social distancing, and it would make it easier if I knew I couldn’t transmit the virus to her.”

More interesting, having just turned 60, Honigsbaum might end up being called for a licensed vaccine before the Novovax trial is finished.

One big issue coming to light: whether companies will “unblind” a participant’s status – in other words, tell them whether they’ve received the experimental vaccine or a dummy. That might influence their decision. Will a dropout also agree to come back for check-ups? Follow-up checks are used to gather long-term safety data, which regulators will want to see.

And there is an additional safety issue: if a person has received one or two experimental shots, what will be the effect of adding a second vaccine, even if it has been approved? It is unlikely to be a worry, Professor Faust explains, but it will be important to monitor those who end up having multiple different vaccines. One option being discussed is a national study that collects blood samples from this mix-and-match cohort of patients.

As far as “who gets the vaccine first”, the general thought is that provided the vaccine reduces disease in older people, who are most at risk of death and disease, the general population will then be vaccinated by age from the oldest first and down to those aged 50 and over. Younger age groups will be included depending on supply. Children, who seem virtually immune to coronavirus, may be considered for immunisation depending on their contribution to transmission, and the vaccines’ safety profiles.

The fact that Covid-19 vaccines will find their way into such a wide range of people – young and old, sick and healthy – means that the promising news from Pfizer and Moderna is the beginning, not the end, of the story. Researchers are still urging people to sign up for trials; more than 300,000 in the UK have obliged, and 500,000 in the U.S. but the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases says the U.S. really needs one million volunteers especially more volunteers from diverse backgrounds. They are especially keen to recruit from black, Asian and minority ethnic communities, who are underrepresented in clinical testing but are up to twice as likely to become infected with coronavirus.

And as the Wellcome Trust noted on its blog this weekend, we’ll need a range of vaccines that can work for a range of people. At this stage, we don’t have the complete efficacy data for the vaccines emerging from phase III clinical trials, including how effective they are for people of all ages, from different ethnic backgrounds, with different immune systems, and in different countries. We also don’t know how long immunity might last for, or whether the vaccines stop transmission of the disease. Said Charlie Weller, Head of Vaccines Programme at Wellcome, who writes about COVID-19 for the Wellcome blog:

“With these unanswered questions, we can’t rely on one or two vaccines to help us gain control of the pandemic. And it might be that one vaccine is not as effective for everyone. We often need multiple vaccines for a disease, to be able to protect different groups. For example this year in the UK we’re using four different flu vaccines – the decision for which one is given is based on a person’s risk group and how their immune system might respond. The vaccine given to a teenager with a robust immune system is not the same as the vaccine given to someone over the age of 65.

If we have a varied Covid-19 vaccine portfolio, we can be confident to find the right vaccine for every person.”

It’s enormously important that we have a range of vaccines, not just for the volume of doses, but so we have vaccines that work in different ways. It is entirely premature to take our foot off the gas at this point.

As far as the larger issues, fodder for a subsequent post. I spent part of the weekend looking at reports debating whether COVID-19 will become more, or less, dangerous. One rather lengthy research paper suggested that the virus was mutating to become more infectious. However, this hasn’t been proven. Neither is there evidence to show that the virus is causing more severe disease as it spreads, or is becoming less infectious. Viruses do mutate, but the mutation rate for SARS-CoV-2 – about two mutations a month, or every second or third transmission – is similar to other RNA viruses like influenza.

And what will the next pandemic be, because we know it is coming. Science magazine and Nature magazine (to name but two of the many) have detailed there are thousands of viruses in animals with the potential to infect people – but a pathetically small number of teams are studying them systematically to identify the main risks. But we do know what needs to be done to reduce the specter of further pandemics:

• Reduce habitat destruction that increases the risk of contact between humans and wild animals

• Eliminate markets for wild animals

• Develop epidemic and pandemic plans (and test them)

• Ensure there are good stockpiles of personal protective equipment

• Improve surveillance for new diseases

• Respond quickly to outbreaks

International scientific and political collaboration and coordination are also essential. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that good science and good governance are essential to prevent and fight pandemics. Alas do we really have the political or organization will to do anything?

More to come.