A record of not creating any new tech companies, so a strategy of just throwing its toys out of the pram and blaming America for its own failures.

But is a new antitrust argument forming?

10 November 2020 (Chania, Greece) – Margrethe Vestager, the European commissioner who oversees competition, has announced formal antitrust charges against Amazon over how it uses data about the merchants on its platform. The case focuses on the online retailer’s dual role, both as a marketplace for third-party vendors and also as a competitor which sells its own goods. The charge sheet, which is part of a probe that started nearly two years ago, fleshes out concerns that Amazon may be abusing its role by using the data it gathers on merchants to compete against them.

The statement of objections comes as antitrust officials across the 27-country bloc, the United States and elsewhere are increasing their scrutiny over how these companies operate across the global digital economy. Amazon was quick to rebut:

“We disagree with the preliminary assertions of the European Commission and will continue to make every effort to ensure it has an accurate understanding of the facts. Amazon represents less than 1 percent of the global retail market, and there are larger retailers in every country in which we operate.”

Amazon’s response was in line with its long-standing policy to play down antitrust concerns, noting that many retailers have their own private label offerings, and that online sales represent only a small sliver of the overall retail sector. Independent merchants are free to use some or all of Amazon’s services and can expand their reach and start selling online with limited initial investment, the company has noted many times before.

The Commission on Tuesday also opened a separate in-depth investigation into Amazon’s alleged favoring of retail offers that use its logistics and delivery services. Brussels will investigate the criteria that Amazon sets to select the winner of the Buy Box – a pop-up window showing customers additional products when they proceed with a purchase – and to enable sellers to offer products to Prime users.

Two immediate points:

• By focusing on Amazon’s potential misuse of data, the Commission is opening up a new line of attack against some of the world’s most powerful companies, and is following in the footsteps of national regulators, notably those in Germany, who have similarly focused on the e-commerce giant’s online activities over the last 18 months.

• Vestager held out the possibility that the EU would work to settle the complaints with Amazon. As I have noted in previous posts, she was forced to acknowledge that large fines “have not helped to remedy the dominant positions of Big Tech companies”.

There is a lot to unpack here and I will address the EU approach to regulating technology in my monograph (a draft of the EU chapter should be out next week) but I’ll outline a few points:

• Most retailers have private label, Amazon is only a single-digit percentage of retail, and Amazon in fact enables independent merchants who might not exist otherwise. So many antitrust advocates assume the world is static and that consumers – or suppliers, for that matter – have no choice in the matter. To that end, even if Amazon uses 3rd-party sales data, the company doesn’t require exclusivity from its 3rd-party merchants; rather, it is those third-party merchants that clamor for access to Amazon’s customers and massive investments in fulfillment. If they believe that Amazon is using their data unfairly … well, don’t sell on Amazon.

• That 3rd-party merchants don’t want to do that – just as newspapers or wannabe “Aggregators” (I’ll come to that in a moment) don’t want to stop Google from indexing their site – isn’t a demonstration of Amazon’s illegal market power, but rather an attestation to how well they serve customers. So many people start their searches on Amazon – very much by choice, given that they can access any website in the world – that merchants see it as worth the risk. And again, as Amazon notes, there are a good number of those merchants that would not exist without Amazon. It seems counterproductive to punish Amazon for creating opportunity.

And on a personal note … oh the irony that a continent that relishes in keeping stores closed on Sunday to the detriment of everyone gets upset when someone creates convenience for consumers and they actually vote with their feet. If you want to live in the 9th century, don’t use the internet. Don’t pretend to want competition. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could find a way to run a government with the same kind of focus on lowering costs, incredible customer service focus, user friendly customer interfaces etc that Amazon have used to enhance our lives?

Banning Amazon would be the only way to stop Europeans from using it, because Europeans are incapable of launching their own alternative. Europe has taxed, regulated, and legislated all innovation out of the continent and the best and brightest emigrate … or get jobs leaching off government posts (I’m talking to you, Boris). The U.S. gave us the internet (yes, France gave us minitel but stumbled on the business model. Great story. It’s in my monograph). The U.S. gave us the iPhone and an App Store that transformed the world, and Europe gave us Nokia ring tones. The U.S. indexed all of the knowledge of the world and made it freely searchable, and Europe created a right for criminals to hide their past.

But let’s move on.

All of this keeps coming back to the “Aggregator-Platform” distinction developed by Ben Thompson (more below) which many of us see as the key to understanding the blistering complexity of technology, competition and what is/is not “antitrust”.

There are so many benefits to these large companies, for both users and small suppliers, that as long as there is nothing locking either in, I am exceptionally wary of regulators thinking they know better. Platforms are different, because they actually leave no alternative – if Apple blocks your app, you’re toast, there is no “a click away” – which is why I think they are much more deserving of regulatory time and attention.

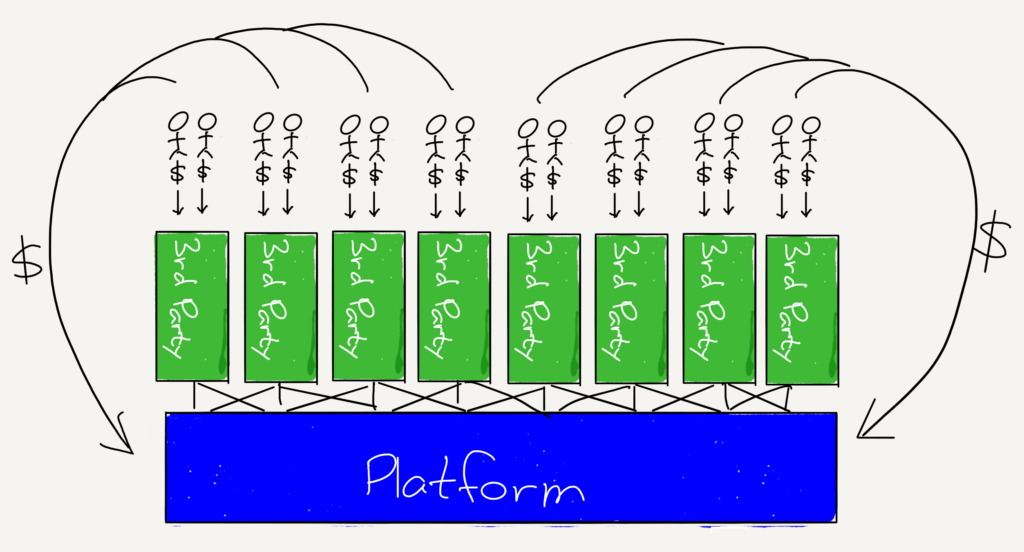

This is ultimately the most important distinction between Platforms and Aggregators: Platforms are powerful because they facilitate a relationship between 3rd-party suppliers and end users; Aggregators, on the other hand, intermediate and control it. The actual big, integrated players – Google and Facebook – integrate customers and research and development to dominate marketing; DTCs (direct-to-consumers) may have online retail operations, but that is a modularized – and thus commoditized – part of the value chain (and meanwhile, Amazon continued to integrate retail and logistics).

Despite the fact that Amazon had effectively split itself in two in order to incorporate 3rd-party merchants, this division is barely noticeable to customers. They still go to Amazon.com, they still use the same shopping cart, they still get the boxes with the smile logo. Basically, Amazon has managed to incorporate 3rd-party merchants while still owning the entire experience from an end-user perspective. Aggregators tend to internalize their network effects and commoditize their suppliers, which is exactly what Amazon has done.

And Amazon benefits from more 3rd-party merchants being on its platform because it can offer more products to consumers and justify the buildout of that extensive fulfillment network; 3rd-party merchants are mostly reduced to competing on price. That, though, suggests there is a platform alternative – that is, a company that succeeds by enabling its suppliers to differentiate and externalizing network effects to create a mutually beneficial ecosystem. That alternative is Shopify, and Shopify will play a large role in every antitrust argument.

The Characteristics of Aggregators

Aggregators have all three of the following characteristics; the absence of any one of them can result in a very successful business (in the case of Apple, arguably the most successful business in history), but it means said company is not an aggregator.

1. Direct Relationship with Users

This point is straight-forward, yet the linchpin on which everything else rests: aggregators have a direct relationship with users. This may be a payment-based relationship, an account-based one, or simply one based on regular usage (think Google and non-logged in users).

2. Zero Marginal Costs For Serving Users

Companies traditionally have had to incur (up to) three types of marginal costs when it comes to serving users/customers directly.

• The cost of goods sold (COGS), that is, the cost of producing an item or providing a service

• Distribution costs, that is the cost of getting an item to the customer (usually via retail) or facilitating the provision of a service (usually via real estate)

• Transaction costs, that is the cost of executing a transaction for a good or service, providing customer service, etc.

Aggregators incur none of these costs:

• The goods “sold” by an aggregator are digital and thus have zero marginal costs (they may, of course, have significant fixed costs)

• These digital goods are delivered via the Internet, which results in zero distribution costs

• Transactions are handled automatically through automatic account management, credit cards payments, etc.

This characteristic means that businesses like Apple hardware and Amazon’s traditional retail operations are not aggregators; both bear significant costs in serving the marginal customer (and, in the case of Amazon in particular, have achieved such scale that the service’s relative cost of distribution is actually a moat).

3. Demand-driven Multi-sided Networks with Decreasing Acquisition Costs

Because aggregators deal with digital goods, there is an abundance of supply; that means users reap value through discovery and curation, and most aggregators get started by delivering superior discovery. Then, once an aggregator has gained some number of end users, suppliers will come onto the aggregator’s platform on the aggregator’s terms, effectively commoditizing and modularizing themselves. Those additional suppliers then make the aggregator more attractive to more users, which in turn draws more suppliers, in a virtuous cycle.

This means that for aggregators, customer acquisition costs decrease over time; marginal customers are attracted to the platform by virtue of the increasing number of suppliers. This further means that aggregators enjoy winner-take-all effects: since the value of an aggregator to end users is continually increasing it is exceedingly difficult for competitors to take away users or win new ones.

This is in contrast to non-aggregator and non-platform companies that face increasing customer acquisition costs as their user base grows. That is because initial customers are often a perfect product-market fit; however, as that fit decreases, the surplus value from the product decreases as well and quickly turns negative. Generally speaking, any business that creates its customer value in-house is not an aggregator because eventually its customer acquisition costs will limit its growth potential.

One additional note: the aforementioned Apple and Amazon do have businesses that qualify as aggregators, at least to a degree: for Apple, it is the App Store (as well as the Google Play Store). Apple owns the user relationship, incurs zero marginal costs in serving that user, and has a network of App Developers continually improving supply in response to demand. Amazon, meanwhile, has Amazon Merchant Services, which is a two-sided network where Amazon owns the end user and passes all marginal costs to merchants (i.e. suppliers).

Platforms Versus Aggregators

Google and Facebook are products of the Internet, and the Internet leads not to platforms but to aggregators. While platforms need 3rd parties to make them useful and build their moat through the creation of ecosystems, aggregators attract end users by virtue of their inherent usefulness and, over time, leave suppliers no choice but to follow the aggregators’ dictates if they wish to reach end users.

The business model follows from these fundamental differences: a platform provider has no room for ads, because the primary function of a platform is provide a stage for the applications that users actually need to shine. Aggregators, on the other hand, particularly Google and Facebook, deal in information, and ads are simply another type of information. Moreover, because the critical point of differentiation for aggregators is the number of users on their platform, advertising is the only possible business model; there is no more important feature when it comes to widespread adoption than being “free.”

The two most-discussed companies, Facebook and Google, are not really platforms at all: they are aggregators, and the difference is significant. Yes, both aggregators and platforms ultimately rely on attracting end users.

The critical point, though, is that what ultimately makes a platform worth using in the long run is the applications that run on it. If you listened to Apple talk about the new improvements to the iPad a few months ago you heard Cook describe the new iPad as “something that instantly transforms into virtually anything that you want it to be”. The transformation of glass is what happens when you open an app. One moment your iPad is a music studio, the next a canvas, the next a spreadsheet, the next a game. The vast majority of these apps, though, are made by 3rd-party developers, which means, by extension, 3rd-party developers are even more important to the success of the iPad than Apple is: Apple provides the glass, developers provide the experience.

Apple improves the iPad by making it a better platform for developers. Specifically, being a great platform for developers is about more than having a well-developed SDK, or an App Store: what is most important is ensuring that said developers have access to sustainable business models that justify building the sort of complicated apps that transform the iPad’s glass into something indispensable.

What’s fascinating to consider is that it’s arguable the iPad would actually be in a much better position were it owned by Microsoft: the company is at its core a platform company that has long bent over backwards to accommodate its developers even at the expense of the user experience. That, though, is the rub: in consumer markets the only way to gain the prerequisite scale to be a platform is to first have a superior product, like Apple. More than ever each has what the other needs.

What About Amazon?

So where is Amazon? Certainly the long-term progression, particularly AWS, is towards being a platform. Then again, AWS as a platform is very different from Windows or iOS. Look again at this illustration:

In the traditional platform model, the platform monetized via end users: they were the ones that actually bought Windows PCs, or Macs and iPhones. This is a very different model than AWS: no end user pays AWS directly; they pay the service that runs on AWS, which pays Amazon. That means that Amazon is competing not as an aggregator in the slightest, but as a pure infrastructure provider, where the only differentiators are features, price, and a tendency towards sticking with a choice already made.

HOWEVER … Amazon.com, on the other hand, is much more akin to an aggregator. Certainly the company is a platform for 3rd-party merchants, but its attractiveness to those merchants and general power over suppliers is rooted in its ownership of the customer relationship. To that end, in the long run, perhaps the most interesting antitrust question (outside of Google and Android) ends up being Amazon’s retail arm.

Hence the EU Commission attention: Amazon’s own brand of products, expanding on existing private-label efforts that include batteries, baby products, clothing, household goods, etc., etc. The brands are available only to Amazon Prime subscribers, who pay monthly or annual fees in exchange for fast delivery as well as video and music streaming.

The implication of being both an aggregator and a platform is that Amazon is uniquely placed to use its platform providers as de facto customer research: see what people want to buy, and then make its own version, and leverage its ownership of discovery to put its products at the top … a point made in delicious detail by Lina Khan in Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox.

More to come.