The biggest takeaway is a sense of bearishness about Slack. This is the sort of action you take when you feel deeply threatened.

The Dude Abides

24 July 2020 (Chania, Crete) – This Monday one of the more notable Congressional hearings in Silicon Valley history is set to take place. The 15-member House Judiciary Antitrust Subcommittee will ask questions of Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, Apple CEO Tim Cook, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, and Google CEO Sundar Pichai. The event is what’s known as an evidentiary hearing: members of Congress are gathering evidence as part of a 13-month investigation into competition and digital marketplaces. The outcome could be legislation that seeks to rein in the market power of these giants, limiting their ability to create monopolies. Or it could turn out to be one more theatrical tech hearing in a series of them, where members of Congress look to score points with gotcha-style questioning as CEOs furrow their brows and promise that a member of their teams will follow up on that later.

As I have noted in several earlier pieces, regulators are still grappling with an age in which we have been “platformed”. What sets the new digital data superstars apart from historical firms is not their market dominance; many traditional companies have reached similarly commanding market shares in the past. What’s new about these companies is that they themselves are markets. Yes, markets have been around for millennia; they are not an invention of the data age. But digital data superstar firms don’t operate traditional markets; theirs are rich with data which gives them enormous power. It’s why data protection is so futile, as I have explained in numerous posts. This weekend I’ll have a full analysis of what to expect from Monday’s hearing.

Interestingly, Microsoft is conspicuously absent from Monday’s proceedings, but Slack is determined to make sure that Microsoft is a part of the conversation. From yesterday’s Financial Times:

The workplace messaging app Slack has filed a formal antitrust complaint against Microsoft with the EU, accusing the tech group of unfairly bundling its rival app Teams with its Office 365 tools. The complaint accuses Microsoft of “illegal and anti-competitive practice” and of abusing its market power to eliminate rivals in an alleged breach of EU competition law. “Microsoft has illegally tied its Teams product into its market-dominant Office productivity suite, force installing it for millions, blocking its removal, and hiding the true cost to enterprise customers,” Slack said in a statement…

Jonathan Prince, vice-president of communications and policy at Slack, said his company’s offering was of higher calibre than Microsoft’s and that it threatened the US tech giant’s “hold on business email, the cornerstone of Office”. He said: “But this is much bigger than Slack versus Microsoft — this is a proxy for two very different philosophies for the future of digital ecosystems, gateways versus gatekeepers”…

Slack wants Brussels to force Microsoft to sell Teams separate from Microsoft Office, said a person with direct knowledge of the complaint.

Slack CEO Stewart Butterfield blasted a Tweetstorm yesterday and noted Ben Thomson, who earlier this month had a piece on Microsoft and competition:

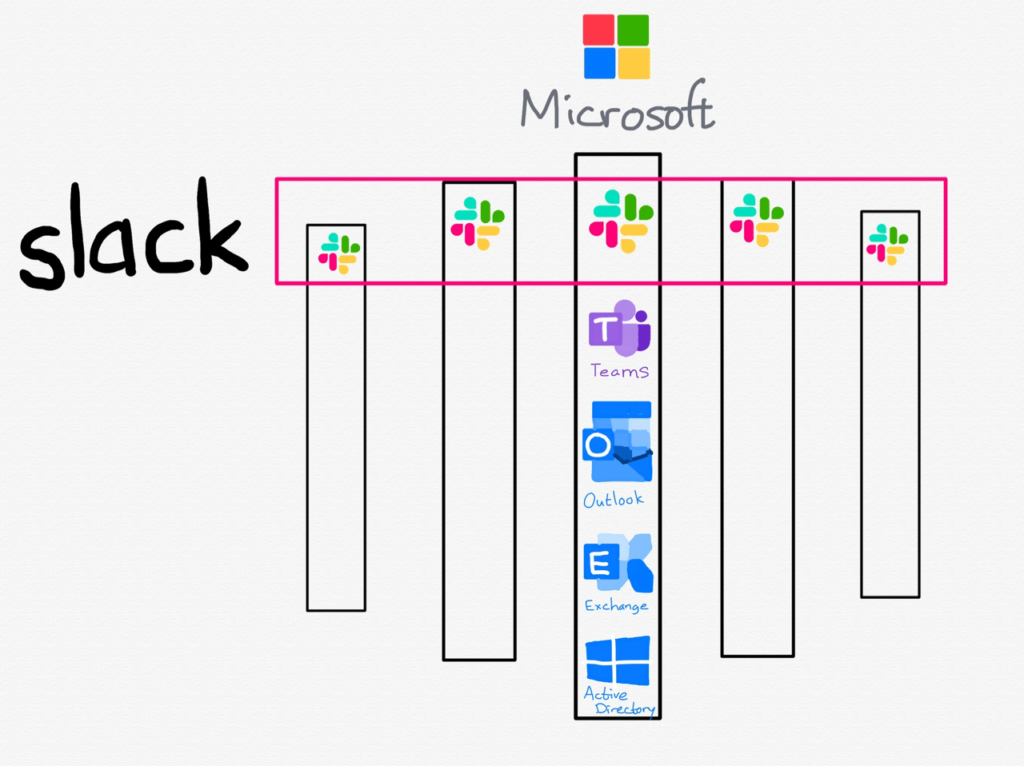

Ben’s piece is long so to summarise, he posited that Teams was beating Slack for three reasons:

• First, Teams is bundled with Office 365, and most companies use Office 365; this is the point that Butterfield is referring to.

• Second, Microsoft has a superior ground game, both in terms of direct sales but also its entire partner and integrator ecosystem.

• Third, Teams is actually better than Slack, at least from a certain perspective.

It’s this last point that is consistently missed by Microsoft skeptics and I’ll quote from Ben’s piece:

This is what Slack — and Silicon Valley, generally — failed to understand about Microsoft’s competitive advantage: the company doesn’t win just because it bundles, or because it has a superior ground game. By virtue of doing everything, even if mediocrely, the company is providing a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, particularly for the non-tech workers that are in fact most of the market. Slack may have infused its chat client with love, but chatting is a means to an end, and Microsoft often seems like the only enterprise company that understands that.

To that end, I gave Slack credit for its focus on Slack Connect: if Microsoft was going to integrate within a company, Slack could focus on being the enterprise social network. As Ben sketched out:

This complaint, though, highlights a big mistake in the analysis. Teams is actually good, particularly for non-tech companies and their workers that simply want everything to work together. Such a company, by definition, is not going to bother parsing the difference between a network-focused chat app and Sharepoint-with-lipstick. Both are marketed as communication apps, which is exactly how they are going to be judged. And, given that, why would these low information companies bother with Slack when they already have Teams – both do chat, right?

Tying in the U.S. and the E.U.

What is noteworthy is that the success of Slack’s complaint likely rests on this same question.

First off, notice the reference to “tying”, which is a legal term for an activity that was long considered per se illegal under antitrust law. Tying is the practice of compelling a customer to buy one product in order to get access to another; the problem with assuming it is always illegal is that nearly all products contain multiple items. A car, for example, comes with tires, which are its own market; at the same time, is it a market failure for a car company to sell a car with tires of its choosing? To that end, over the last 35 years, the Supreme Court has limited the cases in which tying is per se illegal, instead directing lower courts to apply a rule-of-reason analysis, which weighs the benefits of tying against the downsides, and rules accordingly.

The most famous example of this sort of decision, though, was not made by the Supreme Court, but rather the DC Circuit Court of Appeals in United States v. Microsoft. The District Court initially found that Microsoft was guilty of tying according to the per se test — i.e. it found that bundling Internet Explorer with Windows was tying, and thus illegal — but the Appeals Court ruled that the District Court should have used a rule of reason test to decide if the tying was illegal. That, though, never happened, because the U.S. government settled with Microsoft before the District Court ruled.

The European Commission, meanwhile, actually did resolve its suit against Microsoft; what is interesting is that the European Court of First Instance (now known as the General Court) applied what looks a lot like a rule-of-reason test to Microsoft’s bundling of Windows Media Player, or, to be more specific, endorsed the European Commission’s approach which required that:

(1) the company concerned is dominant in the tying market;

(2) the tying and tied goods are two distinct products;

(3) the tying practice is likely to have a market distorting foreclosure effect; and

(4) the tying practice is not justified objectively or by efficiencies. Point number four in particular sounds a lot like a rule of reason sort of approach.

In that case, and again two years ago in the Google Android case, the European Commission found that the ability to download alternatives to Windows Media Player and Google Search and Chrome was not a sufficient defense against the illegal effects of tying. That, by extension, suggests that if Office 365 is found to be dominant, the fact that Slack can be used alongside Office 365 will not be a sufficient defense to charges that bundling Microsoft Teams is illegal.

That, though, is why the question of what exactly Teams is will loom large. The Court of First Instance ruled in the Microsoft case:

The Court notes that, as the Commission observes both in the contested decision and in its pleadings, Microsoft does not show that the integration of Windows Media Player in Windows creates technical efficiencies or, in other words, that it ‘lead[s] to superior technical product performance’ (recital 962 to the contested decision).

What is significant about this is that had Microsoft demonstrated the benefits of integration, it could have prevailed; of course Google failed on this point — although the European Commission decision has not yet been ruled on by the Courts — but I suspect that Microsoft has a better argument with Teams than Google does with Search and Chrome. If it can make the case that Teams being integrated with Office results in superior outcomes for end users, the company could win. In other words, in this particular case, the U.S. and E.U. are actually closer in their approaches than it might seem.

That noted, the case law, at least in the European Union probably does favor Slack (presuming that Office 365 is found to be dominant, and Teams primarily a chat app), particularly given the leeway which the European Commission has to define those questions of efficiency.

Microsoft Competition Concerns, Then and Now

Leaving aside the relevant regulations for a moment, the overall optics of this move are really not great. This is a company that “welcomed” Microsoft to the market with a smarmy ad professing to teach them how to compete. And then, Microsoft did just that, with a product that actually worked with the products people were already used to using (to be cynical, Slack was fine with Sharepoint, but considers Sharepoint-that-works uncompetitive).

Moreover, as Casey Newton noted in his blog last night, this line from Slack’s press release, Tweeted by the company’s Twitter account, is rather disingenuous:

Casey’s points:

Microsoft is not acting like a gatekeeper, at least not for Slack. There are zero technical limitations stopping any Office 365-based organization from using Slack. And while Slack’s reference to a gateway is ostensibly about Slack’s integrations with other applications, it is hard to escape the sense of entitlement usually seen in the consumer space from apps that don’t understand why they should have to convince users to enter their URL or download their app, but rather expect Google or Facebook to do their customer acquisition for them, for free. Slack wants regulators to make Microsoft price its zero marginal cost software in a way that fits Slack’s business model, because customers are making choices Slack doesn’t like.

That is not to say that Microsoft doesn’t present real antitrust concerns, even beyond the tying issues I noted above; the more that data moves to the cloud the deeper potential lock-in becomes. Indeed, the very fact that Microsoft’s out-of-the-box integration is so useful is in part because Microsoft takes the time to make sure different applications work together, but also because Microsoft shares data between its own apps easily, sometimes with APIs it doesn’t expose to competitors.

So, to put it in old Microsoft terms, while the bundling of Internet Explorer dominated the headlines, the real problem was Microsoft’s leveraging of its API, including widespread allegations about special capabilities for Office; today the headlines may be about bundling Teams, but the potentially bigger issue is special capabilities for other Microsoft applications, particularly when it comes to accessing data.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway, though, is a sense of bearishness about Slack: this is the sort of action you take when you feel deeply threatened, and the nature of this complaint makes it seem like Slack is feeling its addressable market constrict like a python as would-be customers standardize on Teams. Here Butterfield’s focus on the Snap comparison resonates: the social network said in its quarterly earnings (yes, I read this stuff for my TMT clients) that it gained fewer users than expected during the lockdown; Instagram gave folks Stories which axe it’s membership skyrocket, but Snap never came up with something new to attract new users at the rate it once did (that ended up being TikTok).

Slack’s attempt to build a social network may be facing a similar fate.

The potential legal argument between Slack and Microsoft certainly seems to be more than a discrete business disagreement between an established giant and a pesky “intruder”. This action perhaps gives us a sort of preview of what’s to come for all future app “homes” or environments.

By “homes”, I refer to where an individual app lives, whether by itself (a standalone such as Slack) or as part of a bundle (MS Word, Excel, Teams, etc. or Google’s bundle for instance). Given those two types of homes or communities in the broader sense, is there a trend that is peeking out from behind the curtain? In fact, is that curtain being ripped away rather than gently pulled aside?

We can see one indicator in the eDiscovery discipline and its related apps. There are a plethora of apps or tools or software…however one wishes to refer to them…that are standalone products offered by specific companies as their main financial resource. Granted, the variety is shrinking due to buyouts and mergers on a grand scale, as newcomers appear that are really just blinking stars eagerly waiting to be sucked into the black hole of some major app. But as a perfect example of the curtain moving back, Microsoft (yet again) may be an example of a major software company establishing a new model, by its attempt to integrate eDiscovery processes and tools directly into its Office365 suite. Will we see some of the top-tier eDiscovery companies such as Exterro or Zasio among others ultimately blend into two or three software suite communities, losing their identification as individual “homes” that consumers gravitate to for a specific need?

And the ultimate question rears its head in the midst of that turmoil: What would this scenario do to inventiveness and intuitive creativity? It is not that hard to imagine a sense of sameness or bland mimicry creeping into the design of new tools; the threat of curtailing risk or inventive new thought is always there when the goal is to be folded into an existing community.