24 May 2020 (Brussels, BE) – What if the IoT provided us with advanced warning of a pandemic event … but nobody was listening? That’s exactly what happened with COVID-19 in the United States, according to Inder Singh, CEO of Kinsa Health, a company that makes connected thermometers. Singh made this bold statement earlier this week on a “Stacey On IoT” virtual event titled, “Why didn’t the IoT predict COVID-19?” And Stacey is Stacy Higginbotham, the IoT maven.

Also on the panel were Dr. Jennifer Radin, an epidemiologist at the Scripps Research Translational Institute, and Dena Mendelsohn, director of health policy and data governance at Elektra Labs, which tests and compiles data on consumer-grade medical devices around what and how they track health information.

NOTE: I am averaging about 6 Zoom chats a week so I thought I’d share a few with my listserv.

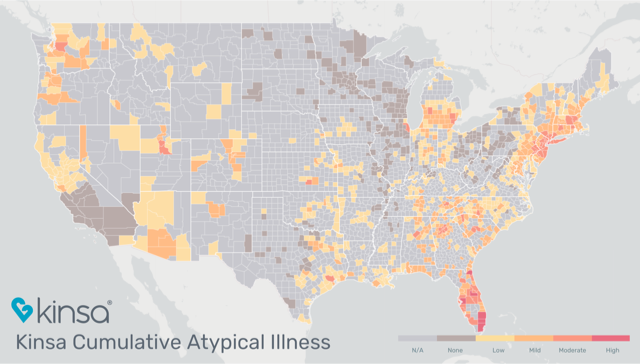

A screenshot of Kinsa’s data showing atypical fevers across the U.S.

Neither Radin or Mendelsohn disagreed with Singh, who subsequently proved his case by sharing Kinsa data from around the country – which is freely available online – that shows body temperature spikes in normal situations. The first sign of an abnormal health situation across the U.S. population appeared in early March, roughly three days before the CDC noted COVID-19 hotpots in the northeast region of the country as well as in Florida.

Three days might not sound like much of a warning sign, but there’s another interesting correlation in Kinsa’s data.

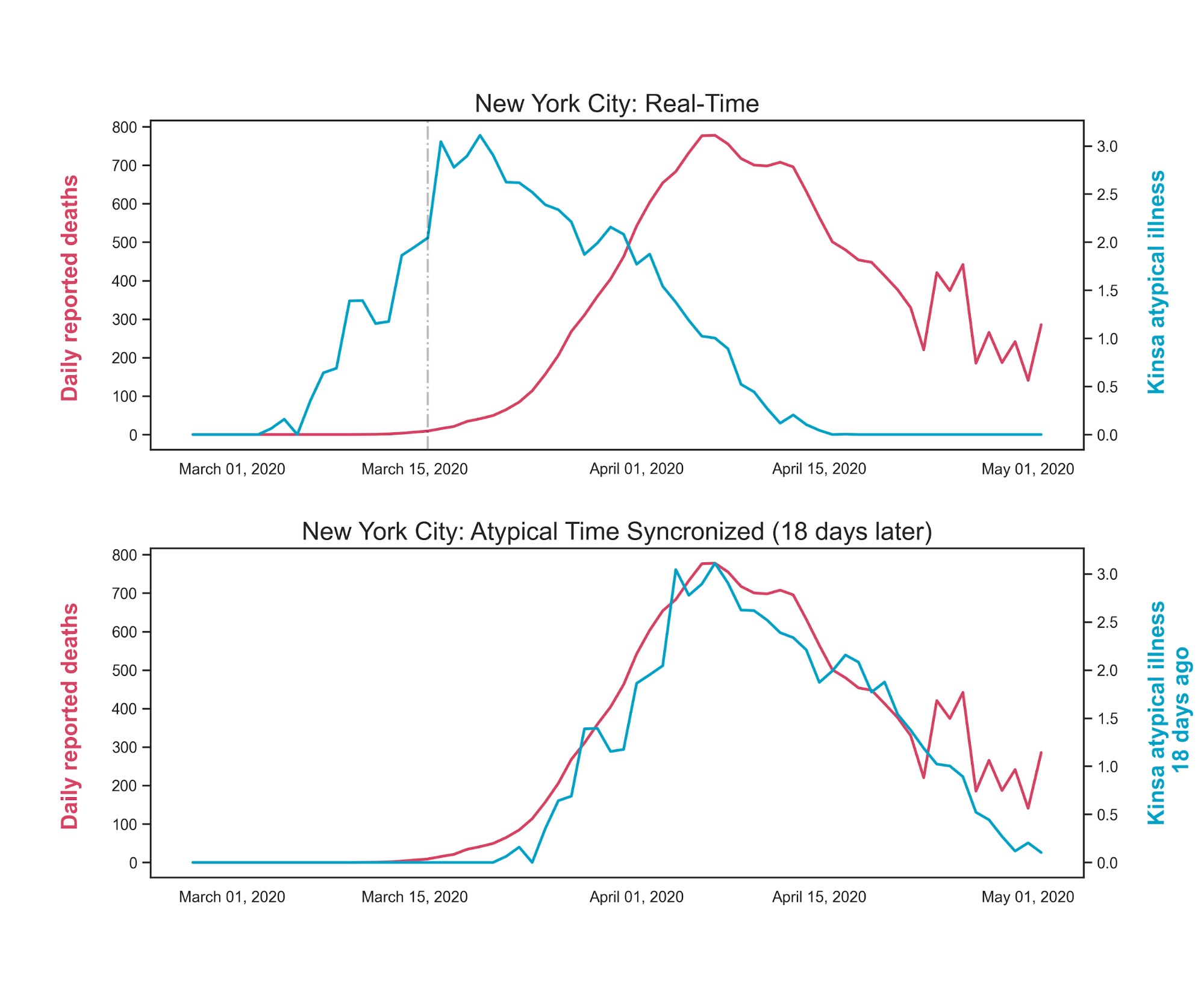

Singh first showed a two-month graph of abnormal temperatures in New York City, then it lined up with a graph illustrating the number of COVID-19 deaths in the same region. There’s a clear correlation between the two when adjusted for 18 days. In other words, we had a nearly three-week “early warning” health predictor between abnormal temperatures and COVID-19 cases that, sadly, ended in thousands of deaths.  Radin also believes in such early warnings, which Singh said is a better term than “syndromic surveillance.” She has previously used the measurements of 47,000 Fitbit users to suggest that such data can predict influenza outbreaks. That report is currently being verified in a public study for U.S. residents that wear health-tracking devices that support data from both Apple Health and Google Health. People can participate by donating their historic and real-time health data from these wearables to the DETECT study using a mobile app called MyDataHelps.

Radin also believes in such early warnings, which Singh said is a better term than “syndromic surveillance.” She has previously used the measurements of 47,000 Fitbit users to suggest that such data can predict influenza outbreaks. That report is currently being verified in a public study for U.S. residents that wear health-tracking devices that support data from both Apple Health and Google Health. People can participate by donating their historic and real-time health data from these wearables to the DETECT study using a mobile app called MyDataHelps.

So, we’re all set with an early warning detecting system for COVID-19 and other potential illnesses, right? Not so fast, said Elektra’s Mendelsohn: “Because COVID-19 is so novel, to date no current tech gadget is the magic bullet for tracking or monitoring COVID-19. Fever is present in many cases of COVID-19, but it’s not present in all of them.”

The other issue, said Mendelsohn, who agreed in principle with Radin and Singh on the benefits of real-time health monitoring sensors, is that not all tracking sensors and wearables measure health metrics the exact same way. That’s where Elektra Labs comes into play. When the company evaluates medical devices that track health info – devices that could potentially be used as early warning detection systems – it asks some key questions:

• Does the technology record accurate measurements?

• Is it measuring relevant information based on symptoms?

• Can people use the tech at home and is it readily available to all sections of the population?

• Are there potential differences between home devices and medical devices?

Sensor-enabled devices that meet the necessary criteria can indeed be used to detect the onset of deadly illnesses, which can, in turn, help stem their spread. As Singh noted, “When someone ill enters the health care system, it’s two weeks too late.”

Of course, regulations and data privacy are critical to establishing such early warnings. If the law doesn’t protect personal information or the companies that provide solutions don’t handle that data responsibly, consumers won’t share it, which reduces the effectiveness of any system that gets put in place. Dr. Radin said the DETECT study has an Institutional Review Board asses their use of data, and that participants can “choose to share as much or as little data as they want.”

Kinsa’s approach, meanwhile, has always been to provide population-level information, not personal or identifiable health data. According to Singh, Kinsa rarely shares de-identified data because there’s always the potential to use it to re-identify individuals. Moreover, he said, the company has only shared de-identified data four times, “and that was to researchers, along with specific, non-sharing clauses they agreed to.”

From a privacy standpoint, Mendelsohn noted that current HIPAA laws don’t apply to health-tracking devices directly. She added that one of the reasons people lose control over their private health data is that it gets used by organizations to make decisions on everything from insurance rates to new hires.

“There’s a difference between data rights and privacy,” Mendelsohn said, though consumers typically equate them. Data rights are more of a legislative framework outlining what data will be used for and how, and giving consumers the ability to see and potentially delete what they don’t want shared with others. Privacy is more akin to opening or closing the door to your personal information, either providing or restricting access to it. Singh said it’s possible to have both “100% privacy with data rights and useful information for early warning health systems.”

Aside from the technical and data challenges, what else is needed for the IoT to help predict illness outbreaks? Funding, funding, funding.

All three panelists agreed that the federal government isn’t yet investing in early warning systems populated by wearable or other personal sensor data. As a result, there is little federal funding for these projects and the new devices that monitor personal health.

Instead, the U.S. continues to fund what it always has at the federal level – prevention techniques and medicinal research, as well as less technical approaches – with no tangible funding available from state and local governments. Dr. Radin said we need more data streams for predictive models, which is why the DETECT program openly shares its findings with public health officials. As they see the value in the data, it could lead to more funding advocacy.

That funding is essential when it comes to researching technical, “21st century” approaches to using health data in predictive models. The challenge isn’t really how to use sensors or interpret data, although there are still some improvements that can be made there from a standards perspective. It’s how to get public health officials to believe in the data provided by IoT devices, do the appropriate scientific research to validate results, then use that information to take proactive instead of reactive steps.

Based on the panelists’ comments, it sounds like in some cases, IoT is ready to predict the next outbreak. We’re just waiting for the government to start ensuring sound data rights and enough of the U.S. population to have wearable devices so as to provide large streams of secured health information. Perhaps the next time IoT alerts us of an impending epidemic, someone will be listening.

To watch the entire event, click here: