The debate over the universalist approach to Holocaust memory

24 April 2025 — The internationally recognized date for Holocaust Remembrance Day corresponds to the 27th day of Nisan on the Hebrew calendar. It marks the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. In Hebrew, Holocaust Remembrance Day is called Yom Hashoah.

This year is it remembered today, 24 April 2025. This week I have been buried in 65 notebooks and 30+ document folders and 120 hours of film footage as my team and I (finally) begin the slow task of editing my film on genocide, taking time to film some connecting clips to make it a seamless narrative.

But today triggered my memory on a recent story that somewhat puts The Shoah and Gaza in perspective. The following essay is a work-in-progress but this draft caught the eye of a publisher with whom I shared it last night, and who now wishes me to expand upon it. So I share it with you, with the proviso some pieces need more exposition, and a serious editor needs to take a scalpel to it.

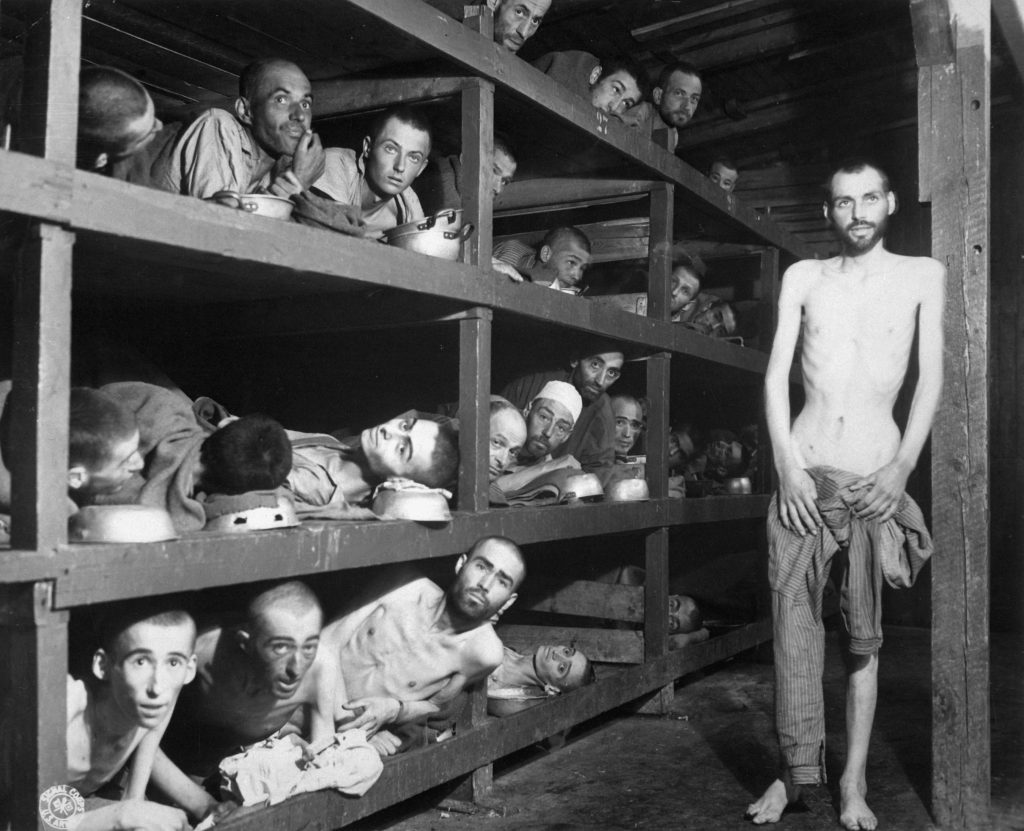

Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar, Germany, on 16 April 1945 when U.S. troops entered the camp. Eli Wiesel can be seen in the second row, seventh from left.

On the 1st of April, the memorial site at the former Buchenwald concentration camp announced that the Israeli philosopher Omri Boehm would no longer be speaking at the eightieth anniversary commemoration of the camp’s liberation on the 19th of April. Boehm, who teaches at the New School in New York, was disinvited because of pressure from the Israeli embassy. It was announced he will give his lecture at a later date. The director of the memorial site, Jens-Christian Wagner, said that the reason for the decision, with which Boehm agreed, was to protect Holocaust survivors from political conflict. Wagner also described the controversy as “the worst thing I’ve experienced in twenty-five years of memorial work”.

How did an Israeli philosopher, the grandchild of a Holocaust survivor, become the object of such a campaign by the Israeli government? Boehm is an outspoken critic of Netanyahu as well as a proponent of a binational resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He is also a Kantian philosopher with universalist, Enlightenment commitments.

It seems that it is precisely Boehm’s universalist humanism that is the problem. On 2 April, the Israeli embassy in Germany articulated its reasons for demanding Boehm’s disinvitation:

The decision to invite Omri Boehm, a man who has described Yad Vashem as an instrument of political manipulation, relativised the Holocaust and even compared it to the Nakba, is not only outrageous, but a blatant insult to the memory of the victims. Although these claims of Holocaust relativisation are false, the embassy’s accusation situates the Boehm affair directly in the tradition of recent “comparison controversies”, such as arose when the journalist M. Gessen compared Gaza to a Nazi ghetto.

For the Israeli embassy, it would seem, any perspective that does not assert the absolute uniqueness of the Holocaust amounts to “relativization” and reduces the Holocaust’s importance. This leads Israel’s representatives to reject the consensus terms on which the Holocaust has been institutionalised as a “cosmopolitan” memory – that is, as a memory of universal importance. As the embassy put it:

Under the guise of science, Boehm is attempting to dilute the commemoration of the Holocaust with his discourse on universal values, thereby robbing it of its historical and moral significance.

In a sarcastic follow-up post on X two days later, the embassy doubled down on its rejection of universalism: it attacked Jens-Christian Wagner, despite his decision to remove Boehm from the commemoration, and accused the director of performing “fashionable intellectual acrobatics”. The embassy then deployed a comparison far more provocative – not to say offensive – than anything in Boehm’s own writings: inviting Boehm to speak at a Holocaust commemoration, it suggested, “is like inviting Bashar al-Assad to give a lecture on human rights”.

Boehm does not question the singularity of the Holocaust nor does he compare the Holocaust and Nakba as historical events. Clearly nobody who wrote that piece has ever read him.

He does, however, recognize that they each make demands on the present and have become entangled in the politics of Israel and Palestine – as Hannah Arendt and others long ago predicted they would. In his book Haifa Republic, for instance, Boehm argues that “both the Holocaust and the Nakba are central to Israel’s fraught past” and that to achieve peace “the perspective from which the events are recollected” must undergo a “fundamental reconsideration”. Through such a reconfiguration of memory, Boehm suggests, a kind of forgetting can also take place that would allow both Israeli Jews and Palestinians to begin to put traumatic pasts behind them and forge an egalitarian democratic future.

In the speech that Boehm would have given at the Buchenwald commemoration – and that was published instead in the Süddeutsche Zeitung and in English in Haaretz – he reasserts his universalist position while rejecting facile comparisons:

When people talk about the brutal massacre of 7 October these days, they sometimes say “Never again!” Others look at the destruction and hunger in Gaza and say the same thing. In so far as both statements imply a comparison with the Holocaust, the one is as misleading as the other.

This critique of comparison is not a rejection of the imperative expressed in the slogan “Never again”, but rather a call to universalize it. “Never again” cannot apply only to particularities: it cannot mean, as Boehm puts it, merely ‘never again for us’. Rather:

“Never again” is only valid in its universal form. A world in which the repetition of the horrors of Buchenwald is still possible is a world in which these horrors could repeat anywhere – and can also impact Jews.

The Israeli embassy was correct that Boehm takes a universalist approach to Holocaust memory, even if the accusations of relativization by way of comparison misrepresent his arguments.

Regardless of his actual views, however, what is most significant in this controversy is the embassy’s rejection of universality. In severing the Shoah from “universal values” the embassy rebuffs decades of mainstream discourse on why we should remember the Holocaust. It retreats far behind Elie Wiesel’s 1979 articulation in the founding document of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum that “the universality of the Holocaust lies in its uniqueness: the Event is essentially Jewish, yet its interpretation is universal”.

The embassy also rejects the 2000 Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust, which emerged from a conference on Holocaust memory and education attended by representatives of 46 states (Wiesel was the honorary chairman). The Stockholm Declaration, much of which was drafted by the Israeli Holocaust historian Yehuda Bauer, states unequivocally in its first paragraph: “The unprecedented character of the Holocaust will always hold universal meaning”.

This universalist message, which has been described as exemplary of a “cosmopolitan memory” was embraced at the time by the Israeli state, which took part in the Stockholm Forum from the beginning and remains a member of its successor organization, the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. In turning on Omri Boehm, an avowedly universalist, Enlightenment defender of cosmopolitan principles, the Israeli embassy has delivered a serious blow to a cosmopolitan Holocaust memory that Israel and its representatives helped to shape.

At a moment when Israel is accused of genocide at the International Court of Justice – and in the opinions of many human rights organizations and prominent Holocaust scholars – a universalist memory of the Shoah is apparently too much to bear.

The recognition of the “pastness” of the Holocaust is happening in a culture where the presence of the event has been entrenched in the last generation. Recognition of its pastness is not equal to forgetting, nor is it simply a result of the passing of 80 years since 1945. Indeed, it is partly a result of the very intense public and professional preoccupation with the Holocaust, the cumulative effect of which has been to make the event not only an integral part of German, Jewish, and European history, but also into a central moral event in human history.

Knowledge is a key to a new understanding. We know infinitely more about the Holocaust today than we did in 1970, 1980, 1990, or 2000. The shock of Holocaust representation – think for example of Claude Lanzman’s 1985 Shoah, or Art Spiegelman’s 1986 Maus, or more importantly Steven Spielberg’s epic historical drama film Schindler’s List in 1993.

All of these have been absorbed by our culture and given way to sombre reflection. The startling revelations of continuous historical studies have made their way into mainstream historiography. The Holocaust shocked and startled because it was so much part of the present.

But in Israel, times are changing. Look at this generated image from a popular Israeli website:

On the left is the tattooed arm of a Holocaust survivor. On the right is a survivor of the Nova party, the site of Hamas’ most lethal massacre. The caption says “we will not forget and we will not forgive“.

Several of my friends and contacts in Israel tell me the 4th generation of the Holocaust has become the 1st October generation. That is the meaning of this image. They have found the way to outsmart time. One friend told me:

This is our loop, our inextricable bond – with ourselves alone. We inhabit the same universe as our ghosts. No one else is allowed to enter. The memory of the holocaust enhances the memory of 7.10.23 and vice versa. There are no other memories or lessons to be learned. It may be a vicious circle. That is of no importance. The only thing that matters is that it is our circle. Our time flows as we want it to flow.

Even the laws of physics bounce off the ramparts we weave from memory and desire. Murderous solipsism. We alone are real.

What we have across the world is politicians searching for verbal formulas that can appease public opinion while providing moral cover to the carnage in Gaza. It hardly seems believable, but the evidence has become overwhelming: we are witnessing some kind of collapse in the free world.

At the same time, Gaza has become for countless powerless people the essential condition of political and ethical consciousness in the 21st century – just as the First World War was for a generation in the West.

And, increasingly, it seems that only those jolted into consciousness by the calamity of Gaza can rescue the Shoah from Netanyahu and re-universalize its moral significance. Perhaps that is a hopeless task.

Many of the protesters who fill the streets of their cities week after week in the U.S. and Europe and elsewhere have no immediate relation to the European past of the Shoah. They judge Israel by its actions in Gaza rather than its “Shoah-sanctified” demand for total and permanent security. Whether or not they know about the Shoah, they reject the crude social-Darwinist lesson Israel draws from it – the survival of one group of people at the expense of another. They are motivated by the simple wish to uphold the ideals that seemed so universally desirable after 1945:

• respect for freedom

• tolerance for the otherness of beliefs and ways of life

• solidarity with human suffering

• a sense of moral responsibility for the weak and persecuted

These men and women know that if there is any bumper sticker lesson to be drawn from the Shoah, it is “Never Again … for Anyone” – the slogan of the brave young activists of Jewish Voice for Peace.

But I think they will lose. I think we have entered a world of unaccountability at on so many levels. I think Israel, with its survivalist psychosis, is not the bitter relic of the past as many would like to believe.

Rather, it is the portent of the future of a bankrupt and exhausted world. The full-throated endorsement of Israel by far-right figures like Javier Milei of Argentina and Donald Trump, and its patronage by countries where white nationalists have infected political life – the U.S., UK, France, Germany, Italy – suggests that the world of individual rights, open frontiers and international law is receding, soon to be gone.

I think Israel will succeed in ethnically cleansing Gaza, and even the West Bank as well, in the name of “security”. They have even said that is their plan,

As I have noted many times before – there is too much evidence that the arc of the moral universe does not bend towards justice. It cannot. There are men, too powerful, who can make their massacres seem necessary and righteous. It’s not at all difficult to imagine a triumphant conclusion to the Israeli onslaught no matter the human cost.

And I imagine the fear of catastrophic defeat weighs on the minds of the protesters. Disbelief over what they see every day in videos from Gaza and the West Bank and fear of more unbridled brutality hounds those online dissenters who daily scream at the pillars of the Western fourth estate for their intimacy with brute power.

Accusing Israel of committing genocide, they seem deliberately to violate the “moderate” and “sensible” opinion that places the country as well as the Shoah outside the modern history of racist expansionism. And they probably persuade no one in a hardened Western political mainstream.

But then all of us, when we address our resentments to the miserable conscience of our time are not at all speaking with the intention to convince. We are just blindly throwing our word onto the scale, whatever they may weigh. Feeling deceived and abandoned by the free world, we air our resentments if only to try and make the crime a moral reality for the criminal, in order that he be swept into the truth of his atrocity.

Israel’s clamorous accusers today seem to aim at little more. Against the acts of savagery, and the propaganda by omission and obfuscation, countless millions now proclaim, in public spaces and on digital media, their furious resentments. In the process, they risk permanently embittering their lives.

But, perhaps … just perhaps … their outrage alone will alleviate, for now, the Palestinian feeling of absolute loneliness, and go some way towards redeeming the memory of the Shoah.