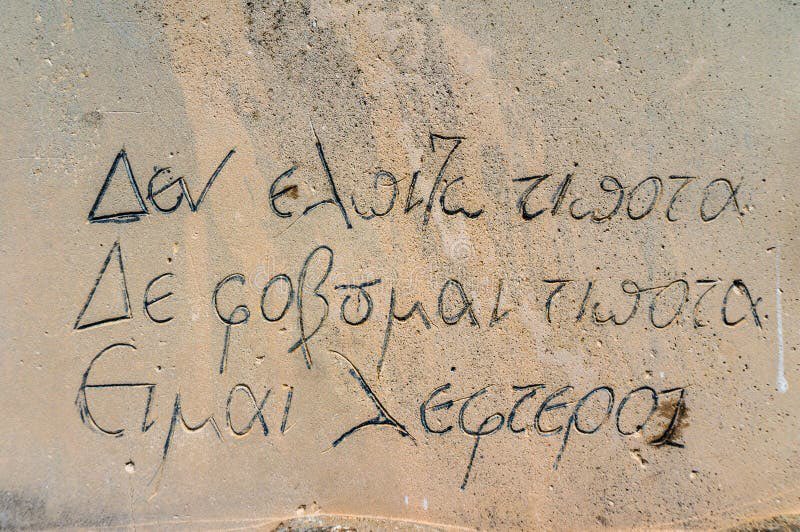

The epitaph on the grave of Nikos Kazantzakis in Heraklion, Crete:

“I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free”.

20 April 2025 — On this Easter Sunday, I turned to Nikos Kazantzakis. I am irreligious and find his work illuminating. Central to many of his works, such as his novels “The Last Temptation of Christ” and “Christ Recrucified”, he questioned Christian morals and values.

As he traveled Europe, he was influenced by various philosophers, cultures, and religions, like Buddhism, causing him to question his Christian beliefs. He never claimed to be an atheist, but his public questioning and critique put him at odds with many in the Greek Orthodox church. The Church tried to excommunicate him, but failed.

But Kazantzakis was simply acting in accordance to a long tradition of Christians who publicly struggled with their faith, and grew a stronger and more personal connection to God through their doubt. Kazantzakis’s interpretation of the Christian faith really predated the more modern, personalized interpretation of Christianity that has become popular in the years after Kazantzakis’s death.

He is considered a giant of modern Greek literature. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 9 different years. In 1957, he lost the Prize to Albert Camus by a single vote. Camus later said that Kazantzakis deserved the honor “a hundred times more” than himself. Kazantzakis died a month later. Camus had always been a great admirer of his work. As my good friend Chris Donegan has noted “ironically, Kazantzakis explored much of the same territory as Camus, but with more humanity and mysticism”.

The novel “Christ Recrucified” (which I re-read this weekend) tells the story of a Passion play put on in Anatolia, where a popular shepherd boy, Manolios, is chosen to play the part of Jesus. During rehearsals, a group of starving refugees arrive. They are from a nearby village that had been devastated by the Turks, but they are turned away.

And the cowardly clergy fear that if it stands with the refugees, the village will turn against the church.

So it, too, rejects the refugees and turns against Manolios who supports them. Manolios had taken his new role as Jesus a little too seriously, they said.

He is murdered by the villagers. “Two thousand years have gone by and men crucify you still,” says Father Fotis, one of the few remaining godly priests.

Not much has changed today.