King’s philosophy speaks to us through the written word, and constitutes his most enduring legacy.

Alas, it is now just history, not to be repeated.

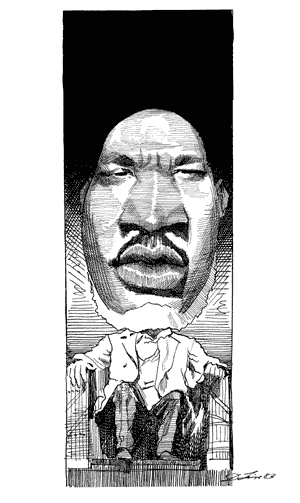

20 January 2025 — “Dissonance” is the theme today (more than usual, that is) as the U.S. presidential inauguration coincides with Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Over the last few months as I took in Gaza and Trump’s re-election and Ukraine and the Los Angeles fires and [oh, just fill in the blank] I have struggled with sane responses to insane times.

It is probably hard for younger generations of Americans in 2025, 57 years after King’s assassination, to fathom just how controversial a figure he was during his career, and particularly around the time of his death. That is because King’s image has undergone a remarkable transformation in these five (almost six) decades. To be honest, over the years, every time the holiday came around I never really paid King much mind.

But this year, I did pay him some mind.

Over the weekend during my annual “book clear”, when I peruse my library collection and select books to be gifted to libraries and friends, I came across The Heavens Might Crack: The Death and Legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. And it fell into a category in my library becoming too common: a book half-read, with lots of my pencil notes in the margin, and stuffed with copies of articles germane to the subject of the book.

And so, I began to re-read the book. In fact, I went beyond that, and I have almost completed it.

As I read it I realized the author (Jason Sokol) is correct. The movement MLK helped to lead has been absorbed into a triumphant story of American exceptionalism, in which the actions of individual people matter less than the dynamism of the supposedly inexorable wave of human progress that swept the country forward from the Declaration of Independence to the civil rights movement. The strength of the opposition to civil rights for blacks, the antagonizing and discomfiting words King used, and the aggressively disruptive tactics he and his supporters employed have been pushed into the background.

What got me at the very beginning of the book was Sokol’s remembrance of the day of King’s murder, his parents screaming “They’ve killed King!” He was 9 years old. I was 17 years old.

He remembered his father’s downcast face, downcast eyes, the resignation of one who had long suspected this would happen – a painful but near-inevitable outcome. Maybe at 9 years old you can sense those feelings. I am not sure what I really sensed at 9.

But at 17 years old, coming from a family who was opposed to King’s efforts, I had a different vibe from my family. And living in an integrated school district that experienced constant social and political conflict I knew what some of this nameless “they” were capable of doing.

Open cruelty was not uncommon in my world, but I was fortunate to move beyond it. More regularly, however, there was faux politeness and friendliness, mixed with an expectation of deference, whites masking their smoldering hostility toward black people. That a person who sought to disrupt that world would draw upon himself actual fire, even though he denounced “eye for an eye” thinking and spoke of love conquering hate, should have surprised no one.

And at the ripe old age of 17 years I was just becoming familiar with people like Stokely Carmichael and Malcolm X.

But Sokol makes a brilliant point early on in the book. He notes that King now fits so comfortably into the present-day popular understanding of American history that one might think that nearly all Americans had supported him enthusiastically from the very start, and that his murder was a tragic event unmoored from any wider opposition to his activities. His birthday is a national holiday. There are streets named for him in cities and towns throughout the nation. He has a monument in the nation’s capital. Figures like King, Harriet Tubman, and Rosa Parks have now become “safe” in ways they never were when they were operating at the height of their powers. Stripped of their radicalism, they are welcomed as sources of inspiration in the curricula of almost every elementary school in the country.

Well, they were welcomed. As we know, MAGA is stripping out all of this history as fast as they can across as many U.S. school districts as they can.

And isn’t it wonderful. King especially has become useful to both liberals and conservatives, who use language from his speeches and writings to support their irreconcilable views about the best direction the country should take on matters of race.

Conservatives have exploited his call for judging people by the “content of their character”, rather than the “color of their skin” to fight affirmative action, while liberals insist that King was speaking of a world to come that could only be brought into existence through the use of race-conscious measures for as long as they were needed. This seemingly universal desire to accept King has come at a cost. Making him all things to everyone fogs the clarity of his moral vision and severely undervalues the contributions he made to this country.

Recovering and, in some cases, discovering the real Martin Luther King is a big theme in Sokol’s book. Whether chronicling his days as a young seminarian, poring over his writings, or recounting the final period of his life, he insists that after all that has been written about the man, we have yet to take his true measure.

Criticism of the image of a benign King-who-suits-everyone is not new; a recalibration of his image has been underway for years now, prompted mainly by the belief that the radical nature of his views, especially his economic beliefs, has been minimized in an effort to create a King who can be accepted by Americans of any race or political persuasion. Despite the myriad books, articles, documentaries, and a feature film about his life, the author suggests that we do not know the real King. Doing justice to the man who gave his life for a cause we claim to honor, he insists, requires coming to a better understanding of who he actually was.

But Sokol does a remarkable job. His piece on the latter part of King’s life reminded me that it was not only his challenge to segregation that made him a hated figure. King’s “Social Gospel critique of American capitalism” also incited forces of reaction, including the John Birch Society, White Citizens’ Councils, and the FBI (read: J. Edgar Hoover), who all launched disinformation campaigns to discredit King and his movement.

King intended from the start of his public career to work to end racial discrimination and poverty for all Americans, a fight that would proceed in two phases:

1. The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, which killed de jure segregation, was the culmination of the “first phase.”

2. That done, King started to speak even more openly and insistently about the “second phase”, which would be a “struggle for economic equality”, with unions as the linchpin of this effort. King, along with his aide Bayard Rustin, had long thought that there should be a “convergence” between unions and the civil rights movement.” Everything was at stake for King here: if the second phase of his plan for social transformation was successful, “everyone could have a well-paying job or a basic level of income, along with decent levels of health care, education, and housing”.

He soon found, however, that “union racial politics remained contradictory and complicated.” The same racism that permeated American society also had a firm grip on the union movement. As had been true throughout American history, many poor and working-class whites had no interest in solidarity with blacks against white elites. King’s efforts to support black unionism and to forge an alliance between the black and the white working classes reveals the arduous effort that he put into this project, most heartbreakingly in his final years, when he drove himself to exhaustion.

King had already drawn connections between the civil rights movement and unionism at the beginning of his career, joining, in the words of the historian Thomas Jackson, “a vanguard of activists who were vigorously pushing a combined race-class agenda in the late fifties.” In a 1957 speech he voiced the hope that the union movement would spread, and that black and white union members would join together in opposition to the most predatory aspects of capitalism. King rejected communism, but even before he became an activist, he questioned the basic morality of the country’s economic system, writing in 1952 to his future wife, Coretta:

I am much more socialistic in my economic theory than capitalistic. Capitalism has outlived its usefulness. It has brought about a system that takes necessities from the masses to give luxuries to the classes.

King realized that a truly successful effort to bring about economic justice would require an enormous reallocation of resources.

By 1967, he was willing to speak openly about the country’s need to reassess its priorities. Why, he asked in a speech at Riverside Church in April of that year, should the United States spend money on an immoral and wasteful war in Vietnam when that money could be used to fight a real war on poverty at home? King knew that support for that social war was on the wane as critics portrayed it as a drain on the country’s resources. He countered by singling out the Vietnam conflict as not only a “demonic suction tube” siphoning money from needed social programs, but as evidence of a deep moral crisis in the United States. A country that put “profit motives and property rights” ahead of “people” was easy prey to “racism, extreme materialism, and militarism.”

King’s decision to combine the call for racial solidarity to achieve an economic transformation in the United States with a critique of a war supposedly being waged to stop communism abroad made him the target of a host of sinister forces. He often received messages marking him for death. President Lyndon Johnson was beside himself at what he took to be King’s apostasy. This was probably not just about the substance of King’s words: the concern was also procedural, for King was violating a strongly held, and not so hidden, norm. It was fine for black preachers to do what they had done since the days of slavery: act as intermediaries for and champions of the black community on subjects said to touch directly on its purportedly narrow interests. King was testing boundaries on many fronts.

The two projects that galvanized King in his final year represent the apotheosis of his focus on economic justice: the Poor People’s Campaign and his support for the striking sanitation workers of Memphis, Tennessee – the latter would bring him to his fateful trip to that city in April 1968.

With the Poor People’s Campaign, King hoped to reprise his triumphant 1963 March on Washington by leading thousands of poor people to the nation’s capital to demand a “radical redistribution of economic power.” The effort was fraught from the start, as his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, had neither the funds nor the infrastructure to organize the huge event he envisioned. The task was not only physically draining, it was psychologically difficult. For as King crisscrossed the country to promote the effort, “the right-wing hate campaign against him escalated.” While in Miami to speak to a group of ministers, King remained in the conference hotel because the police could not ensure his safety.

The plight of the garbage collectors of Memphis in the 1960s perfectly illustrated the connection between racial discrimination and economic injustice. The men worked in dangerous and difficult conditions, carrying garbage in tubs on their heads, often with maggots and liquids raining down. They had to bring their own clothes and gloves and had no regular work breaks, and were given fifteen minutes for lunch. They worked from dawn till after dusk with low wages and no overtime pay. The workers, most of whom were too poor to pay union dues, defied an injunction against public employee strikes and marched under banners saying “I Am a Man.” Their situation and their response to it moved King deeply, so much so that he decided to make Memphis the starting point of the Poor People’s Campaign march to Washington.

As nearly every book written about King makes clear, the specter of an untimely death haunted King. He tried to buffer his fear by developing a numb fatalism, a defense against the dread that someone might kill him at any moment. He had survived an earlier attempt on his life in 1958, when a woman, suffering from mental illness, stabbed him in the chest, narrowly missing his heart. In the years that followed, the threats were more clearly politically motivated. He was a man propelled forward by a mission. Writes Sokol:

If dying violently was inevitable, he reckoned, he might as well resign himself to it. He girded himself mentally against the nerve-racking despair of constant panic.

And he quotes Andrew Young, who was with King when he was killed:

He was philosophical about his death. He knew it would come, and he just decided there was nothing to do about it.

King simply pressed on. It is hard to imagine such conviction in the face of all the forces arrayed against him, and to think of just how young King was (in his thirties) as he contemplated the violent end of his life.

And although King was greatly respected by many at the time of his death, there was a general sense that he had peaked – that his time as a leader of black America was coming to a close.

Sokol explores the differing reactions to what happened in Memphis on April 4, 1968:

News of King’s murder stopped people in their tracks and rendered them speechless, moved many to tears and others to celebration, drove some to violence and still others to political activism. Significantly, white contempt for King knew no geographical bounds. To an extent that might shock many today, large numbers of whites across the country were happy about what had happened.

But then things began to change. King’s martyrdom, along with John F. Kennedy’s and Robert F. Kennedy’s, altered the way people saw him. The three men, often pictured together on tapestries and in portraits that hung on the walls of many homes, became symbols of a tragic loss of possibilities. As the years wore on, Sokol writes, “King looked ever more appealing.”

Yet King’s elevation to something like sainthood has obscured the truly herculean effort he put into what was called “the struggle”. The true nature of his labor has been lost.

And yet his magic endures.

King’s great gifts as an orator allowed people to tap into the emotional power of an old-style preacher, whose cadences lifted audiences whether they were listening carefully to his words or not. His uncanny ability to turn a memorable and lyrical phrase, to conjure a vivid metaphor, to stir his listeners’ emotions, and to move people to action across a wide range of audiences allowed for the deployment of an age-old racial categorization: blacks supposedly exist in the realm of emotion, whites in the realm of the intellect.

But that’s the effort you need, to critically engage King’s writings with the aim of rescuing him as a “systematic thinker,” not just a masterful orator and inspiring leader.

And Sokol does not write about the following, but it is noted in a review of his book.

Much has been written about what many saw as the failure of the first black president of the United States, to carry forward King’s legacy. Many black writers had initially supported Barack Obama, but soon began to launch fierce criticisms of the president.

The longing for even a King-like figure is understandable, but the president of the United States, the head of a secular country of over 300 million people with varying views, interests, and aspirations, cannot reasonably be – and should not be – a prophetic leader guided by Christian theology, as King emphatically was. The salient point is that King’s writings blended the theological and the philosophical, as did his speeches. Christianity was central to King’s persona and his plans of action. His understanding of economic inequality and the best ways to deal with it grew out of his belief in the Gospels. “There are few things more sinful,” he said, “than economic injustice.” A man such as he could not reach the highest level of his calling within the confines of the American government.

The horror today? There is no figure aspiring today to take on King’s mantle, America being a culturally fragmented country, and destined to become more so over the next 4+ years. No such person could ever succeed on the national stage.

But for me, there is no way to read Sokol’s book (or any other book about King) without a profound sense of longing, as one muses about what might have been. Through modern technology, we can still hear and see him in recordings of his speeches and interviews, and we will continue to do that as we commemorate his birth and his death.

But King’s philosophy, speaking to us through the written word, may turn out to constitute his most enduring legacy.

Alas, it is now just history, not to be repeated.

BELOW: An interview from 1966. I can only repeat some of the comments you’ll see posted on the clip: he spoke with power, with a sense of calmness, one of the most articulate persons I have ever heard. The style of his tone and how he speaks is like listening to music, an amazing rhythm as he speaks.

And most importantly, he speaks the truth.