Parisians navigating the narrow streets of the 4th arrondissement in recent days may have heard a familiar, yet nearly forgotten, sound. The bells of Notre Dame Cathedral have been ringing again after nearly five years, in preparation for the famed building’s long-awaited reopening.

We are enchanted, in a digital age, by the iconography, the building as a depiction of a moral order and a medieval cosmos, but also by the sheer authenticity of ancient buildings.

7 December 2024 (Paris, France) – Notre Dame officially reopens today with a liturgical ceremony. Tomorrow the cathedral will host a public Mass, and its bells will again begin marking the hours of daily life in the French capital.

On April 15, 2019, at about 6:50 p.m., Frédéric Lenica, the chief of staff to Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo, was among the first to telephone the fire department. Smoke was rising from the roof of the 850-year-old cathedral, and Lenica could see it from Hidalgo’s office. Parisians watched from rooftops as the beloved building burned, and they gasped when the cathedral’s spire crashed through the roof in a torrent of flames at 7:30 p.m.

Those flames were not yet extinguished when French President Emmanuel Macron vowed to rebuild the cathedral, “bigger and more beautiful,” calling it “part of France’s destiny”. He promised it would be done in 5 years, and most restoration experts and architectural experts said “impossible”. He did it in 5-1/2 years and the world was stunned. Last night I watched a special presentation on the Arte TV network (the European public service channel dedicated to culture) which explained the “dream team” Macron assembled, and how it was done.

Macron needs this. He is gravely weakened politically (a situation of his own making) and he hopes to win a new lease of political life from today’s ceremonial reopening of Notre Dame, and the related events over the weekend. Macron will seek to present the renovated cathedral as a symbol of France’s inner reserves of creative strength. In a speech marking the occasion, he will urge the world to see beyond the country’s current political crisis and admire the determination, organization and hard graft that have rescued one of France’s most famous buildings in just five years.

The long-awaited event comes just as France enters a period of deep uncertainty triggered by the fall of Prime Minister Michel Barnier’s government on Wednesday. A replacement has yet to be named. Five-and-a-half years after the devastating fire, Macron had planned to make the cathedral’s reopening the optimistic climax of 2024 – a year also marked by the Paris Olympic Games.

But while he seeks to capitalise on the project’s undoubted success, a contrast is unavoidable between the depressed state of the country as a whole, and the soaring achievement of fixing this magnificent Gothic cathedral.

I have a personal history with this magnificent cathedral. Herein a few reflections.

Like everyone else, I presume, I feel an attraction for zero points, for the axes and points of reference from which the positions and distances of any object in the universe can be determined:

* the Equator

* the Greenwich Meridian

* sea-level

There is a circle on a large square in front of the Notre-Dame Cathedral (the square had disappeared when they were making a new carpark and no one thought to put it back until a number of years ago) from which all French distances by road are calculated. You can even calculate other points across the globe.

But rather than some dry symbol of measurement the spot (known as “Paris Point Zero”) has attracted a number of local rituals, be it of the “wish-granting” variety by throwing a few coins on it, or by spinning in a circle on one foot atop the marker to gain your heart’s desire or kissing a loved one above the plate to ensure an eternal devotion.

Others still pay pilgrimage to the site when they feel that they have experienced Paris to its fullest, using it as a proverbial period in the story of their journey.

No, the “Paris Point Zero” is not the centre of France. But Notre-Dame has occupied the heart of Paris and the French for the better part of a millennium, its twin medieval towers rising from the small central island wedged between the storied left and right banks. It is the center of the center, rising in its audacious immensity from the bedrock of the Île de la Cité, Paris’s historical nucleus. The cathedral has for centuries been enshrined as an evolving notion of “Frenchness”. And in so many people’s imaginations, this feeling that Paris is not supposed to change, that its monuments such as Notre Dame are not supposed to be affected by the passage of time.

I was a student here at the Sorbonne in 1972 and 1973. For me, Paris was everything. My intellectual sauce. Painting, music, political awareness, writing, performance, creating, activism … thriving on repurposing. Trying to make sense of all the changes happening inside myself and in the society around me. And having every opportunity to do it. As Ernest Hemingway wrote “If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you.”

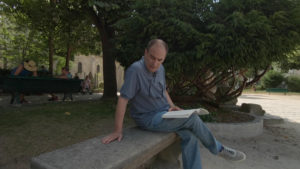

A few years ago we did a special video for the French publishing industry. In one segment I introduced the viewers to “my bench” (still there after all these years, with some of the same pigeon poop, I think) located in a small park across from Notre Dame. It is where I spent many an afternoon studying (and sleeping) across from the cathedral.

I made scores of trips back to Paris thereafter, and have lived and worked here on-and-off for years. Many a night one of the things I love best about this city is taking an after-dinner walk to Notre-Dame with my wife just to soak in the Gothic facade, the monstrous gargoyles and the darkened rose windows. We typically make our way from our flat in the Marais and toward the Pont Louis Philippe to cross the Seine. No matter how many times we’ve seen the ivory towers of Notre-Dame soar above the tip of the Île St.-Louis, they are always breathtaking. Sometimes you see the entire southern facade of the cathedral lit up, its pillars, gargoyles and flying buttresses bathed in bright white.

Or, better yet, during the day, going inside and walking the long, lead-covered stretch of roof flanked by a line of flying buttresses so close that you can touch them. The rooftop on which we walked was destroyed. That rage-filled fire 5 years ago engulfed it. It has now been completely restored.

The fire drove me back to Victor Hugo’s novel Notre-Dame de Paris (retitled The Hunchback of Notre-Dame by English publishers, a title forever imprinted in the minds of countless readers) in search of the soul of Notre Dame when its physical form surely was likely to disappear before our eyes. I went automatically to my favorite digression, Hugo’s long contemplation on how the printing press had replaced architecture as the principal means of conveying meaning to the masses.

Note: the novel is full of these “intermissions”, Hugo’s pontifications on all sorts of subjects.

As Hugo explains, the history of architecture is the history of writing. Before the printing press, mankind communicated through architecture. From Stonehenge to the Parthenon, alphabets were inscribed in “books of stone.” Rows of stones were sentences, Hugo insists, while Greek columns were “hieroglyphs” pregnant with meaning.

Note: And in a way, it is a bit amusing. By the time Victor Hugo’s novel was published in 1831, the building was pretty much a wreck. Hugo called it a “vast symphony in stone” as “powerful and fecund as the divine creation,” and despaired that it had come to be an object of ridicule.

The popularity of his book helped reposition Notre-Dame as a symbol of French identity, inspiring its restoration by the 19th-century architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Viollet attempted to restore the church’s Gothic character, undertaking a vast project of architectural reinvention and private imagination, redoing the figures on the facade, recreating stained glass windows and adding many ornate touches, including to the spire that burned down. When the spire collapsed, all those layers of history seemed to evaporate.

I don’t think Hugo could have predicted we would all watch the destruction of the cathedral in a Twitter livestream. But the cathedral takes up such huge imaginative real estate not only in my mental map of Paris, but, I would guess, in the mind of any tourist who has seen it.

How could it not? It bears the weight of generations of history and of fiction, its image is immortalized on postcards, tea towels, and key rings. It’s a featured stop on any tour, a monument every friend and family member back home asks about. For historians, architects, artists, Catholics, the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris seemed an unshakably constant source of beauty and wonder. It was a helpful cultural touchstone. In conversation everyone could put their hand to the old stone first quarried centuries ago and understand what the other person was talking about. In personal reflection, I never got the sense I was alone with my hand literally or metaphorically on the cathedral stone.

I have often wondered where the spot was that Hugo found the word “Ananke” engraved deeply in the stone. The Gothic calligraphy convinced him it was a hand from the Middle Ages, and the fatalistic, melancholy meaning of the word struck him deeply. “Ananke” is a Greek personification of inevitability. Who had been moved to write such a thing? When Hugo returned to the cathedral the word “Ananke” had disappeared. Someone had painted over it or scraped it off.

I drifted away from religion years ago but I still find the cathedral sacred as far as history. The cathedral is a palimpsest of an edifice — something reused and rebuilt, showing traces of its past under the additional story of each new century. Each generation modified the cathedral according to its needs: a space for Catholic worship remodeled according to new trends and tastes, a storehouse during the French Revolution (with some statues of kings beheaded, according to the then new prevailing ethos), an architectural marvel of the Romantic re-interpretation of the Gothic.

And as noted in Luc Sante’s The Other Paris, the physical trace of the rabble is retained in the oldest parts. It’s been surmised that the stone carvers tasked with creating the hundreds of figures adorning the portals of the cathedral enlisted drunks and vagrants to sit as models. Observes Sante:

Thus, the physical trace of the rabble is retained in the oldest, most august, most sanctified monument of the city.

As Hugo points out in the preface to the novel, “mutilations” come to Gothic cathedrals from every quarter. The priest paints, the architect rebuilds, and the people follow and destroy it. This isn’t even the first or most famous time the cathedral has badly needed repair.

Upon that fragile memory of a vanished word, Hugo wrote the most popular story of the cathedral. It brought the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris to public consciousness not just in France but across the world.

And Hugo wasn’t the only literary great to draw inspiration from the cathedral. Marcel Proust, who is most famous for the six early-20th-century texts that comprise In Search of Lost Time, was also deeply impressed. Notre Dame de Paris was spellbinding for Proust. There is a wonderful book by Mary Bergstein on Proust and photography in which she details Proust’s visual imagination, his visual metaphors, and his photographic resources and imaginings. She notes he was “even known to have thrown a fur-lined overcoat on over his nightshirt and to have stood in front of the cathedral for two hours in order to receive fresh inspiration from the portal of Saint Anne”.

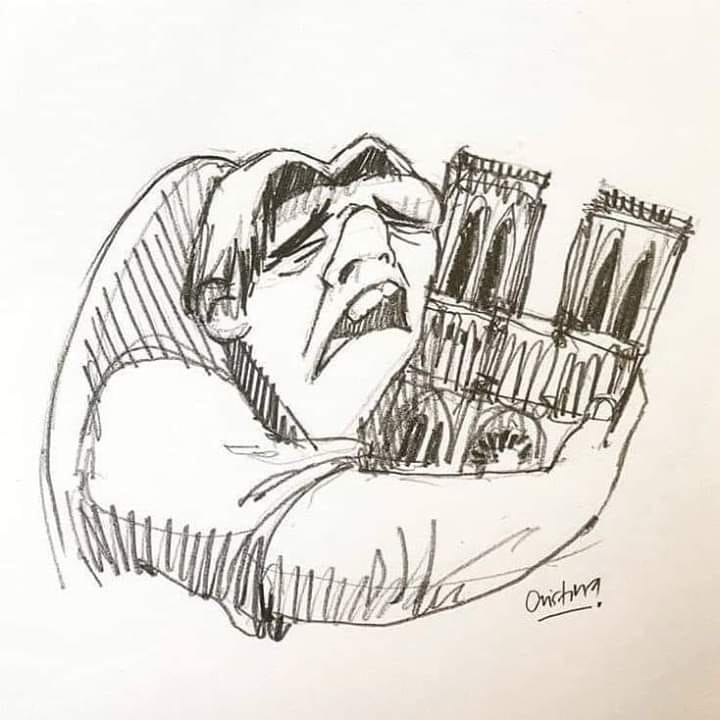

And in a way, the fire’s symbolism was hard to miss

As many had commented that week, France was burning. The fire at Notre-Dame happened on the day that Macron was supposed to explain how he intended to address the demands of the “Yellow Vest” movement. An anguished, restless nation has struggled to cope with the monthslong uprising and with the frayed social safety net that spurred the protests. Generations that had come to rely on this social safety net, as a matter of national pride and identity, see it going up in smoke.

But this fire was not like other recent calamities. When flames killed dozens trapped in Grenfell Tower in London, it exposed a scandalous lack of oversight and a city of disastrous inequities. When a bridge collapsed in Genoa, Italy, also taking life, it revealed the consequential greed of privatization and a chronic absence of Italian leadership. When the National Museum of Brazil burned down, also through unconscionable government neglect, it wiped a tangible swath of South American history from the face of the earth, incinerating anthropological records of lost civilizations.

Notre-Dame, where no one died, represents a different kind of catastrophe, no less traumatic but more to do with beauty and spirit and symbolism. Visited by some 13 million people a year, the cathedral, established during the 12th century, is the biggest architectural attraction in Paris. It is an emblem of the old city – the embodiment of the Paris of stone and faith – just as the Eiffel Tower exemplifies the Paris of modernity, joie de vivre and change.

Not that Notre-Dame hasn’t changed. Scarred repeatedly, it is a kind of palimpsest of French history. Finding its Gothic architecture outmoded and ornate, Louis XIV destroyed much of the church’s interior and swapped it out for one he regarded as more classically tasteful. During the Revolution, insurgents ransacked the cathedral, plundering treasures and decapitating statues of Old Testament figures on the building’s facade, which they mistook for portraits of French kings. They rededicated Notre Dame to the “Cult of Reason”, melting its great bells.

Through its many transformations, Notre-Dame has remained “the great stage where great events in France have been rehearsed and repeated for centuries,” as the historian Robert Darnton has put it – where the cathedral’s archbishop blessed the flags carried by French armies going off to war, before crowds of weeping parents and spouses. Where Parisians wept Monday, as they also did along the banks of the Seine and at the plaza of the Hôtel de Ville.

Back in 1871, the Paris Communards, their revolt dying out, adopted a scorched-earth policy and burned down the Hôtel de Ville, with its paintings by Delacroix and Ingres. So the building from which Parisians watched the fire is a reconstruction. The cathedral had been undergoing an extensive restoration. Gargoyles were broken, balustrades had collapsed, flying buttresses were stained by pollution. Water had seeped through cracks in the spire’s wood frame.

AND TODAY?

France today is still wrestling with how to reinvent itself for a new age. Considering the great sweep of time, that Yellow Vest uprising will no doubt come to seem like just another data point in the long evolution of a nation that has survived setbacks and returned, again and again, to an abiding glory. But today’s political turmoil just might mark a serious shift in French political and social direction.

In his landmark television series “Civilization,” standing before Notre-Dame, the art historian Kenneth Clark asked: “What is civilization? I don’t know. I can’t define it in abstract terms — yet. But I think I can recognize it when I see it.” He then turned toward the cathedral: “And I am looking at it now.”

Someday, the fire of 2019 may well fade into the history of Notre-Dame. And it might take many years to repair todays’ political damage.

But the great cathedral will reinvent itself, too.

The Cathedral last night