It’s no secret that the Republican Party’s rise in the South went hand in glove with the rise of the civil rights movement and desegregation. Dallas was the epicenter of an ultraconservatism that echoes to this day – and the reason for Kennedy’s trip.

23 November 2024 — On November 22, 1963, as he travelled by motorcade through Dealey Plaza in downtown Dallas, the 35th President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, was killed by the bullets of a sniper (two snipers?); one of Kennedy’s traveling companions, the Governor of Texas, John Connally, was also shot.

I was 12 years old at the time of Kennedy’s assassination. In my last year of elementary school, before I would move up to the “big kids school”. We had an “AV Club” at my school. That’s “audio visual”. One of the responsibilities of the AV Club was to wheel into a classroom one of the massive TV sets we had whenever a teacher wanted to show an educational program of some sort.

Note to readers: video tape recorders became commercially available in the U.S. in early 1963. Our school system was very progressive and our school owned several large TVs plus several several video tape recorders and players.

About mid-day the Club’s director (a guy in his mid-30s who had a deep knowledge of TVs and videos and all sorts of electronic things and who peaked my interest in media and telecommunications) came into the classroom where I was, quietly whispered something to my teacher, who motioned me to go with the director. With other members of the Club we wheeled our 3 TV sets onto our basketball court – which at the time I thought was a funny request. There were teachers there already, all sobbing. I had no cue what was going on.

Shortly thereafter the school principal made an announcement for the “older students” to assemble in the basketball court. Once assembled, she quietly, softly told us of the news from Dallas. There was crying and shouting, as teachers tried to comfort the students. I remember the principal saying something about how the day would be historic and that we needed to watch this day, live, as it was happening. I do not remember how long we watched the news of Dallas. But I remember the constant sobbing. And I remember the 4 days of mourning wherein the entire country seemed to close down.

Each time this date comes around I think of that day in 1963. Yesterday, as fortune would have it, I was having a long lunch with an ex-U.S. Marines buddy. Who made the Marines his life, becoming a sniper, of all things. One of these days I’ll write about his thoughts on the computational ballistic analysis of the cranial shot to Kennedy.

And when I got older I learned just how historic the day was.

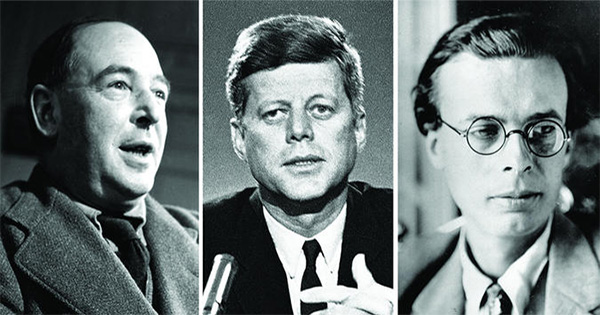

C. S. Lewis died in his home in Oxford, England at 5:30 pm, followed an hour later by the death of John F. Kennedy, followed, seven hours after that, by the death of Aldous Huxley. Three giants, all gone in the blink of an eye. And I am acutely aware that millions of non-famous people also die each day of every year, many of them also giants in someone’s eyes. But on any ordinary day, the death of either author would make headline news. But the 22nd of November 1963 wasn’t an ordinary day.

Unsurprisingly, there are many notable letters related to all of these events – not least Laura Huxley’s account of her husband’s death, which can be read here. She mentions Kennedy’s death.

Last night I read “Lady Bird” Johnson’s account of that day – she being the first lady of the United States from 1963 to 1969 as the wife of then president Lyndon B. Johnson. And I re-read a few chapters from Edward Miller’s book “Nut Country: Right-Wing Dallas and the Birth of the Southern Strategy“. Both will be relevant as I continue my story after this (perhaps overlong) introduction.

Above: when Lyndon Baines Johnson and Lady Bird Johnson visited the Baker Hotel in Dallas in November 1960, Dallas Republican Congressman Bruce Alger led the hecklers who confronted them.

The “Southern strategy” (born in Dallas) was basically the effort by Republicans to generate support among whites in the South. It was very difficult for Republicans to get elected in the South after Reconstruction. Alger (a Dallas Republican elected to Congress in 1954) and John Tower (Texas’ Republican senator from 1961 to 1985) and a number of other people from Dallas developed racial strategies to capture those white voters. The whole point was to make it very clear to African-Americans that the Republican Party was not sympathetic. It was the primary reason for Kennedy’s trip to Texas, to fight their growing strength.

“It all began so beautifully,” Lady Bird remembered. “After a drizzle in the morning, the sun came out bright and beautiful. We were going into Dallas.”

It was November 22, 1963, and President John F. Kennedy and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy were visiting Texas. They were there, in the home state of Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird, to try to heal a rift in the Democratic Party. The white supremacists who made up the base of the party’s southern wing loathed the Kennedy administration’s support for Black rights. They were threatening to go with the Republicans, or split off into their own party.

That base had turned on Kennedy when he and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, had backed the decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in fall 1962 saying that army veteran James Meredith had the right to enroll at the University of Mississippi, more commonly known as Ole Miss.

When the Department of Justice ordered officials at Ole Miss to register Meredith, Mississippi governor Ross Barnett physically barred Meredith from entering the building and vowed to defend segregation and states’ rights.

So the Department of Justice detailed dozens of U.S. marshals to escort Meredith to the registrar and put more than 500 law enforcement officers on the campus. White supremacists rushed to meet them there and became increasingly violent. That night, Barnett told a radio audience: “We will never surrender!” The rioters destroyed property and, under cover of the darkness, fired at reporters and the federal marshals. They killed two men and wounded many others.

The riot ended when the president sent 20,000 troops to the campus. On October 1, Meredith became the first Black American to enroll at the University of Mississippi.

The Kennedys had made it clear that the federal government would stand behind civil rights, and white supremacists joined right-wing Republicans in insisting that their stance proved that the Kennedys were communists. Using a strong federal government to regulate business would prevent a man from making all the money he might otherwise; protecting civil rights would take tax dollars from white Americans for the benefit of Black and Brown people. A bumper sticker produced during the Mississippi crisis warned that “the Castro Brothers” – equating the Kennedys with communist revolutionaries in Cuba – had gone to Ole Miss.

That conflation of Black rights and communism stoked such anger in the southern right wing that Kennedy felt obliged to travel to Dallas to try to mend some fences in the state Democratic Party.

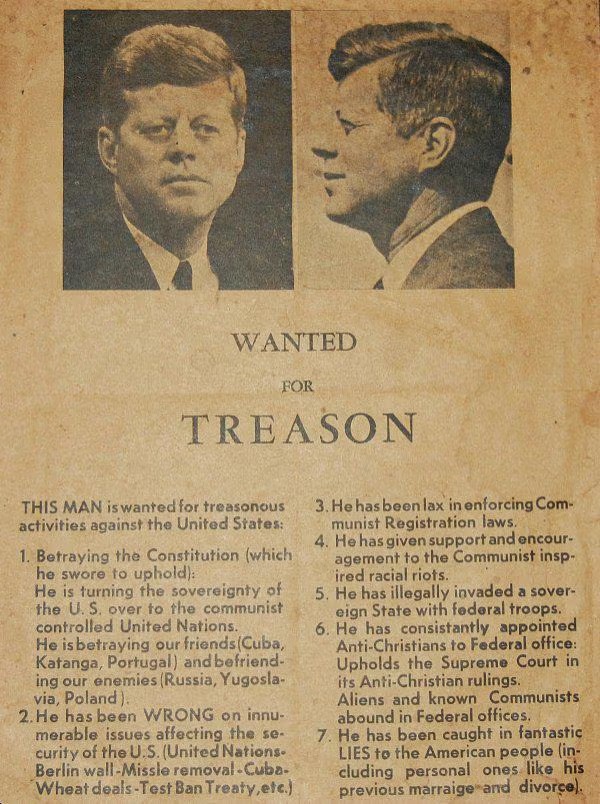

On the morning of November 22, 1963, the Dallas Morning News contained a flyer saying the president was wanted for “treason” for “betraying the Constitution” and giving “support and encouragement to the Communist inspired racial riots”. The flyers were being distributed everywhere.

Kennedy warned his wife that they were “heading into nut country today.”

But the motorcade through Dallas started out in a party atmosphere. At the head of the procession, the president and first lady waved from their car at the streets “lined with people – lots and lots of people – the children all smiling, placards, confetti, people waving from windows,” Lady Bird remembered. “There had been such a gala air,” she said, that when she heard three shots, “I thought it must be firecrackers or some sort of celebration”.

The Secret Service agents had no such moment of confusion. The cars sped forward, “terrifically fast – faster and faster,” according to Lady Bird, until they arrived at a hospital, which made Mrs. Johnson realize what had happened. “As we ground to a halt” and Secret Service agents began to pull them out of the cars, Lady Bird wrote, “I cast one last look over my shoulder and saw in the President’s car a bundle of pink, just like a drift of blossoms, lying on the back seat. It was Mrs. Kennedy lying over the President’s body”.

As they waited for news of the president, LBJ asked Lady Bird to go find Mrs. Kennedy. Lady Bird recalled that Secret Service agents “began to lead me up one corridor, back stairs, and down another. Suddenly, I found myself face to face with Jackie in a small hall, outside the operating room that had her husband. You always think of her – or someone like her – as being insulated, protected; she was quite alone. I don’t think I ever saw anyone so much alone in my life”.

After trying to comfort Mrs. Kennedy, Lady Bird went back to the room where her husband was. It was there that Kennedy’s special assistant told them, “The President is dead,” just before journalist Malcolm Kilduff entered and addressed LBJ as “Mr. President.”

Officials wanted LBJ out of Dallas as quickly as possible and rushed the party to the airport. Looking out the car window, Lady Bird saw a flag already at half mast and later recalled, “[T]hat is when the enormity of what had happened first struck me.”

In the confusion – in addition to the murder of the president, no one knew how extensive the plot against the government was – the attorney general wanted LBJ sworn into office as quickly as possible. Already on the plane to return to Washington, D.C., the party waited for Judge Sarah Hughes, a Dallas federal judge.

By the time Hughes arrived, so had Mrs. Kennedy and the coffin bearing her husband’s body. “[A]nd there in the very narrow confines of the plane – with Jackie on his left with her hair falling in her face, but very composed, and me on his right, Judge Hughes, with the Bible, in front of him and a cluster of Secret Service people and Congressmen we had known for a long time around him – Lyndon took the oath of office,” Lady Bird recalled.

As the plane traveled to Washington, D.C., Lady Bird went into the private presidential cabin to see Mrs. Kennedy, passing President Kennedy’s casket in the hallway.

Lady Bird later recalled: “I looked at her. Mrs. Kennedy’s dress was stained with blood. One leg was almost entirely covered with it and her right glove was caked…with blood—her husband’s blood. She always wore gloves like she was used to them. I never could. Somehow that was one of the most poignant sights—exquisitely dressed and caked in blood. I asked her if I couldn’t get someone in to help her change and she said, ‘Oh, no. Perhaps later…but not right now.’”

“And then,” Lady Bird remembered, “with something – if, with a person that gentle, that dignified, you can say had an element of fierceness, she said, ‘I want them to see what they have done to Jack'”.

All of this history was brought home to me on election night when, with the election outcome certain, Trump brought out a queue of people to speak on his behalf. One was Dana White, who Trump thanked, calling him “a great man”.

White is the chief executive of Ultimate Fighting Championship (the American mixed martial arts promotion company) that is testosterone on steroids. He played a key role in Trump’s second ascension to the White House, helping him reach millions of young (white) male voters, getting him on every white male alt-right program/podcast he could, plus several times on Joe Rogan’s podcast channel – considered to be the most influential and most watched podcasts in the world, and extremely alt-right.

You have seen the numbers. Trump was averaging 15 million viewers on these various podcasts while Kamala Harris, sticking to main stream media, was averaging 4.5-5 million viewers.

White had used his enormous connections to leverage appearances for Trump on these friendly, right-leaning podcasts with millions of young listeners, and he was very upfront about his motivation in connecting Trump with so-called “manosphere” or “bro-casters”, saying the move was intended to tap into young voters:

“You’re getting conversations in these podcasts, and you yourself, as a young kid, get to really see who Donald Trump is, not the bullshit you hear from the far-left media”.

In interview after interview young voters had told CNN (and other organizations doing polling) that they decided to support Trump after listening to podcasts helmed by Joe Rogan and other influential figures.

The latest study from the Pew Research Center showed that 40% of young adults aged 18 to 29 “regularly” get their news only from these types of news influencers, most of whom skew conservative. Trump’s sit-downs with Rogan, Theo Von, Adin Ross, and Andrew Schulz, all of whom boast millions of followers across social media platforms, allowed him to reach directly to young voters without the scrutiny that typically comes with interviews with journalists.

But left unsaid was that every one of these alt-right programs gleefully raise the flag of racist propagandist – with no regrets. Trafficking in ugly misogyny. Proudly. But in in order to reach mainstream Americans, these white supremacists have learned to cloak their racism in disorienting terms like “white politics”.

It brought me back to Miller’s book and the history that led to Dallas’ being labeled “the City of Hate”.

What was the “Southern strategy”, how did Dallas become its epicenter, and how is it reflected in today’s American politics?

It is a long story and best understood by reading Miller’s book. But a few brief points.

The Southern strategy was basically the effort by Republicans to generate support among whites in the South. It was very difficult for Republicans to get elected in the South after Reconstruction. As I noted in the picture caption above, Alger Tower and a large number of other people from Dallas would use racial strategies to capture those white voters. The whole point was to make it very clear to African-Americans that the Republican Party was not sympathetic.

Alger was the first Republican who is able to do this. He personified the whole point of the book: how moderate conservatives and ultraconservatives fought for control in Dallas, forcing public officials to adjust to each new turn. At the time of Alger’s election, it is unheard of to have a Republican congressman from Dallas. But he is elected and becomes one of the country’s most reactionary congressmen. His 1956 re-election campaign is a hugely important precedent for the racialization and the future Southern strategy of the Republican Party.

It marks the first time a Southern Republican had abandoned a measured stance on desegregation and embraced the segregationist position to maintain and build his electoral coalition. He made a political decision to signal to white voters that he was antagonistic toward the interest of civil rights and blacks.

A lot of pressure comes to bear on Alger to change his position on civil rights and adopt a more segregationist position. Alger set a huge precedent that was followed thereafter in a consistent and steady pattern by other Dallas Republicans, as well as 1964 Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater.

But one of the tricks was to use ministers to spur a drive for the spiritual defense of segregation, using the Bible to back up segregation. Using the Bible to support the continuance of segregation.

There were figures trying to dampen that, but they were far less than effective. Ultraconservatism was becoming a very, very powerful force.

And oil money was a big driver of that force, and particularly the money of H.L. Hunt. What started as oilmen trying to make sure they paid low taxes seems to have led to something more radical.

There was presidential Republicanism. There were individuals who supported LBJ and they supported the (Democratic) speaker of the House, Sam Rayburn. These were Republicans who would vote for Democrats.

But many people in the oil business began to support Republicans more frequently in order to maintain the oil depletion allowance (that lowered their tax burden). They were making a lot of money, and they wanted to keep that money. They realized they were moving into the white-collar, upper-middle class, and they realized the tax policies of that particular time were a burden, and they started supporting the Republican Party for the reasons of lessening their tax burden. That was one reason. It wasn’t the only reason.

Hunt’s role in key.

Hunt had a veritable media empire. He had an organization called “Facts Forum” that was involved with television, it was involved with mail and radio. He had a relationship with Dan Smoot, who was a very active commentator on ultraconservative politics that was filled with conspiracy theories and with apocalyptic language that “we are in our last days and that this is the last gasp of liberty”.

All of this leads us to the Kennedy assassination and the description of Dallas as “the City of Hate.” We are told Kennedy was killed by a Marxist, but the fervor of ultraconservatism in Dallas had created enormous antipathy against the president.

The year following the Kennedy assassination, Alger loses his seat in Congress. A lot of Dallasites determined they needed to go in a different direction and quash the ultraconservative language that had become an albatross for them. There’s one story in the book that an activist Republican out gathering signatures for Barry Goldwater heard of the assassination and went home and tore up the signatures. She was just completely convinced Goldwater couldn’t win in those conditions. Many business elements in Dallas determined Alger was an inefficient congressman. He was not able to get the type of pork to Dallas that would be sufficient if Dallas was going to continue to be the Athens of the Southwest. They determined that Earle Cabell, then the mayor of Dallas, would be the better politician.

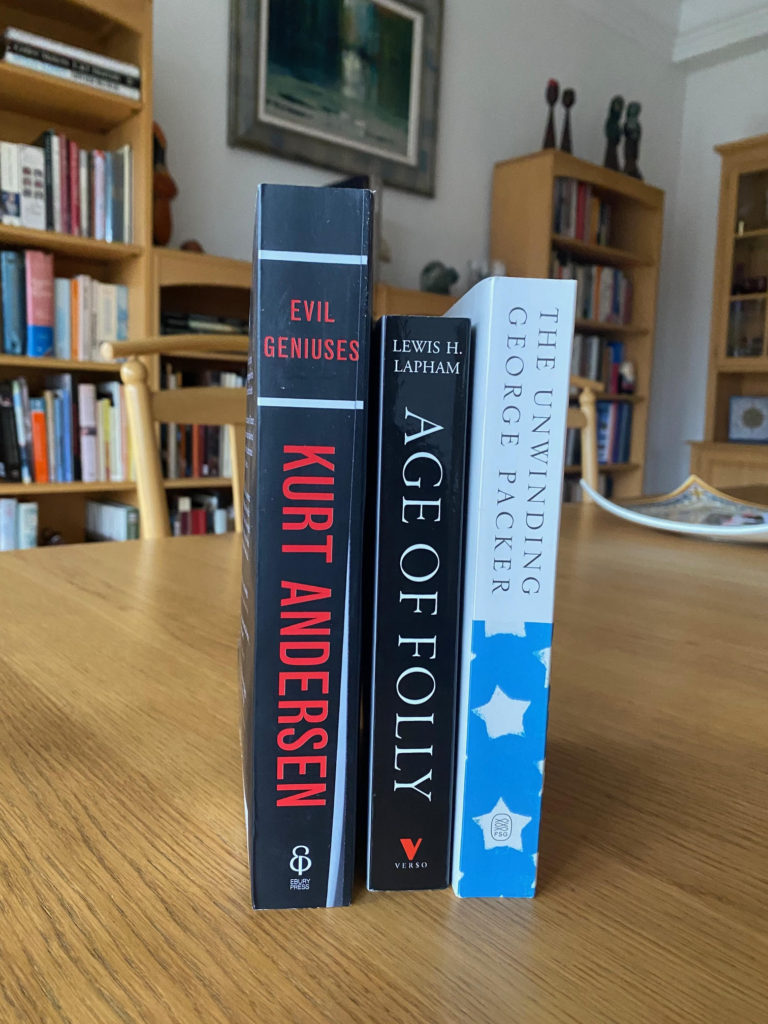

But some of the ultraconservative language you saw prior to the assassination continued. It didn’t completely end there. In fact, it began to build again in the 1970s and you heard that same tone this year, the same tone that dominated Dallas in the middle of the last century. It was called “the tentacles of rage” and it is brilliantly chronicled in three books I have quoted in many posts: “The Unwinding“, “Age of Folly” and “Evil Geniuses“.

The point was that America needed a transformation. Miller’s book shows how a group of influential far-right businessmen, religious leaders, and political operatives developed a potent mix of hardline anticommunism, biblical literalism, and racism to generate a violent populism – and widespread power. Though those figures were seen as extreme in Texas and elsewhere, mainstream Republicans nonetheless found themselves forced to make alliances, or tack to the right on topics like segregation. As racial resentment came to fuel the national Republican party’s divisive but effective “Southern Strategy,” the power of the extreme conservatives rooted in Texas only grew.

George Packer and Lewis Lapham carried that into present day American politics.

I’ll come back to all of these books later this year in my traditional end-of-the-year long form essay, focused on what I think Trump 2.0 means. So for now, let’s conclude.

I saw all of this echoing throughout this year’s presidential campaign. It’s safe to say that a lot of the incendiary speech has certainly trumped the careful deliberation among the right, and conspiratorial thinking that was long a characteristic of “Nut Country” in the 1950s is very much in vogue today. The apocalyptic doomsday rhetoric that ultraconservatives like H.L. Hunt and Dan Smoot and all the others used back then was very much part of the Trump campaign today.

“Disinhibition” is a word that has recently migrated from the lexicon of psychology into that of American politics. It refers to a condition in which people become increasingly unable to regulate the expression of their impulses and urges, and this year it very obviously applied to Trump’s increasingly surreal, vituperative, and lurid rhetoric.

But it now must also apply to the institutions of American government: with allies on the Supreme Court and with control over the Senate and the House of Representatives, Trump will have no one to regulate his urges.

And perhaps it applies to American society, too. This is a disinhibited electorate. It is no longer, on the whole, frightened of its own worst impulses. Up to now it has been possible to take some comfort in Trump’s failure to win the popular vote in either 2016 or 2020, and in the fact that not once during his time in the Oval Office did a majority of Americans approve of the job he was doing. (This was true of no previous president in the era of polling.) It could be said with some justice that he did not really embody America.

But now he does. The comprehensive nature of his victory suggests that alongside the very large core of voters who are thrilled by his misogyny, xenophobia, bullying, racism and mendacity, there are many more who are at the very least not repelled by his ever more extreme indulgence in those sadistic pleasures. They know what he’s like – and don’t much mind.

This is hard for Democrats (and just plain democrats) to get their heads around. Both inside and outside the U.S., liberals and progressives have had a default assumption that, even if their government sometimes does terrible things, Americans themselves are essentially decent and benign.

They are not.

The Harris campaign, with its messages of joy and hope and its (bleakly fruitless) pursuit of an imagined reservoir of Republicans too well-mannered to vote for Trump, rested on the same supposition.

And more’s the pity.

The actual vote came down not to the margin of error but to the margin for error. Half of Americans seem to think that their country has none, the other half that it has plenty. One tribe fears that, after almost a decade of Trump bombarding its laws, institutions, and civic life with verbal and physical assaults, another four years of him in the White House will kill them off for good. Harris appealed to those fears.

But the other tribe thinks the U.S. can afford to gamble its future on a carnival barker, a wild improviser, a reckless disrupter. It has, paradoxically, a deep confidence in the America that Trump disparages with such dark relish, believing that a good shaking-up will not break the country but bring it back to its true self. Trump is a confidence man in both senses – he may be conning much of his own electorate, but they give him the benefit of their nonchalant belief that he is not destroying American norms, merely restoring an imagined American normalcy.

This is something else that made the campaign hard to comprehend. Trump drew a picture of an America on the brink of extinction – but many of his voters trust in an idea of an America that is so fundamentally resilient that it can afford to take breathtaking risks. Harris offered hope in the promise of America – but many of her voters see the country as too fragile to survive another disordered presidency.

More to come.