In “The Language Puzzle”, archaeologist Steven Mithen explores how linguistic and evolutionary development go hand in hand, from our grunt-filled past to our garrulous present

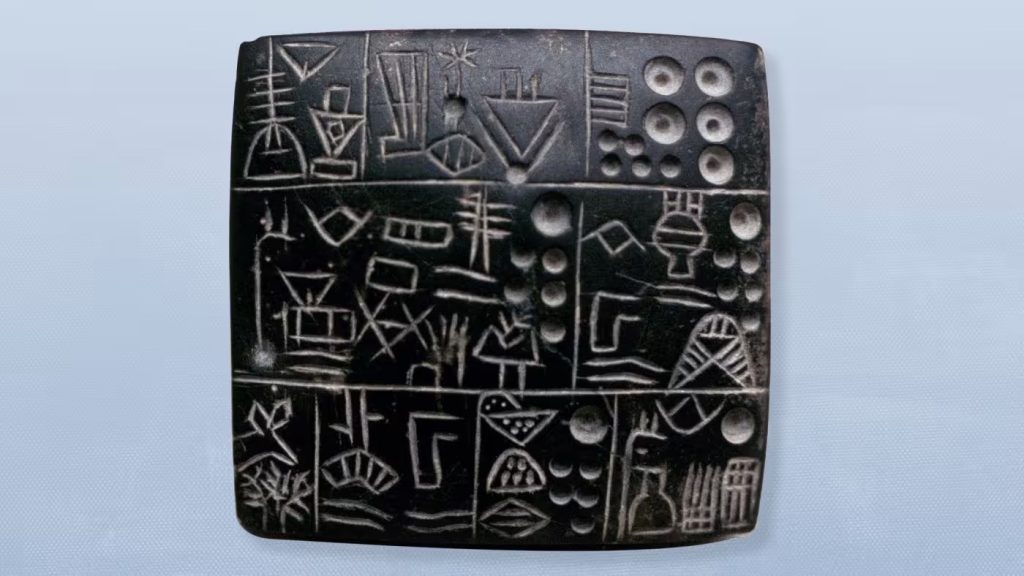

ABOVE: Administrative tablet of stone, dated to the Mesopotamian/Sumerian period, 3100-2900 BC. See further notes on this tablet at the bottom of this post.

22 March 2024 – In 1929, the American anthropologist and linguist Edward Sapir told a group of unwitting study participants that the made-up words mil and mal referred to different-sized tables, then asked them to guess which referred to the bigger table.

Whether the volunteers were English or Chinese, child or adult, about 80 per cent intuitively chose mal. That same year, the German psychologist Wolfgang Köhler pulled a similar trick with maluma and takete, asking people to identify which meant “round” and which meant “spiky”. Maluma was overwhelmingly linked to a round shape; the sharp movements of the tongue required to utter takete led volunteers to associate it with a spiky shape.

These clever experiments shed light on synaesthetic links between vocal sounds and symbolic shapes that might have arisen in our ancestral past. So-called “iconic words”, which show a resemblance between form and meaning, include onomatopoeic terms such as “boom” and “splash”. They, writes archaeologist Steven Mithen in The Language Puzzle: How We Talked Our Way Out of the Stone Age, “would have obviated the need for learning by early ancestors because their meanings can be intuitively grasped”.

Iconic words are just one clue in the enduring mystery of how Homo sapiens came to acquire the flowing, compositional language that is so different from the grunts and screams of our closest relative, the chimpanzee. That history includes genetic mutations that changed brain shape, sparking a cognitive fluidity that facilitated the development of metaphor and abstract thought. Metaphor “enhanced communicative power, including the ability to describe and explain complex technological skills and ideas to others”, Mithen suggests.

That language-driven meeting of metaphorical minds, he argues, created spear throwers, bows and other tools — which further drove linguistic and technological change, supplemented by an evolving vocal tract and hearing apparatus. A command of fire, which extended social activities into the night, turned our ancestors into storytellers by introducing the concept of the supernatural. Somewhere along the line, our forebears added arbitrary words — those named by convention, as opposed to iconic words — to the lexicon.

In short, our ancestors moved from producing the apelike calls of Australopithecus afarensis 4mn years ago, via the iconic words of Homo erectus 2mn years ago and strings of utterances from Neanderthals 50,000 years ago, to the roughly 7,000 languages spoken today. As Mithen writes of the human past, “brain, language and material culture have been bootstrapping each other into modernity”.

Mithen, a professor of early prehistory at the University of Reading whose previous books explore the evolution of culture and music, intended to write a history of farming but, as he explains early on, veered off-script. His hypothesis, barely mentioned after the introduction, is that language gave rise to agriculture around 10,000 years ago. That development was a “crossroads for Planet Earth”, he argues, leading ultimately to towns, civilisation, empires, industrial revolutions and globalization — even the Moon landings.

Instead of ploughing the farming furrow, he was sucked down the rabbit hole of language, which has lured many a science writer before him. Mithen recognises that language is an “all-encompassing brain, body, social and cultural phenomenon” that requires a knowledge of such disciplines as linguistics, psychology, neuroscience, genetics and anthropology, each with its own data, theories, methods and terminologies.

Unfortunately, Mithen feels compelled to give us all of them, in an account that sometimes feels more like a textbook than a work of popular science. The chapter on genetics, for example, starts by explaining DNA, with descriptions of nucleotides, protein production and transcription factors. His tendency to dot every “i” and cross every “t” subtracts from, rather than adds to, the bigger picture.

Nonetheless, as someone with a deep love of language but with little linguistic knowledge (I can speak several languages but I cannot write well in any of them), I learned a great deal from reading The Language Puzzle. Some Amazonian languages lack words for numbers beyond 1 and 2; a gestural origin for language is unlikely because these are largely absent in apes; the debate about whether language influences perception and thought remains alive.

As Mithen writes:

“Whether or not we think in words, they certainly augment our thought. The act of labelling items in the world, whether they are sensations, material objects, actions or abstract ideas, makes them salient and concrete. The ability to find new labels – for example, the noun hundred to represent “ten tens” or aunt to signify a parent’s sister – allows for more efficient thought and the flowering of increasingly complex concepts.

It is only really in the final chapter that Mithen circles back to the Middle East, where agriculture started:

“By 10,000 years ago, the hunter-gatherers of the Fertile Crescent had become farmers. They had talked their way into this new lifestyle by using words to build both the concepts and the technology it required. With such constant talk and chatter, dialogues and gossip, speeches, conversations and tête-à-têtes, it was inevitable that new concepts would arise, inventions be made, and lifestyles would change.”

It is a romantic tale but, in relaying it, our narrator faces the same struggle as others, whether Steven Pinker in The Language Instinct (sympathetic to Noam Chomsky’s idea that we are born with an innate universal grammar) or Daniel Everett more recently in How Language Began (which leans towards culture rather than genetics). There is no neat, easy-to-sequence trail of evidence that leads from the grunt-filled past to our garrulous present.

As Mithen himself acknowledges, the fossil record is sparse, ancestral brain tissue has long gone and we can infer only limited information from the behaviour of chimpanzees, with which Homo sapiens last shared a common ancestor 6mn years ago. Languages, sadly, die out all the time, along with much of the history they encode.

All this highlights the self-referential irony of trying to demystify this almost magical human power through which I am linking my mind to yours. We can only make sense of how our species came to tell each other stories by telling each other more stories.

A few notes on the tablet that leads this post

This stone tablet offers a fascinating glimpse into the administrative practices of Mesopotamia/Sumer during 3100-2900 BC. The tablet, meticulously inscribed with hieroglyphics, serves as evidence of early written communication and record-keeping systems.

Believed to have been used by administrators, possibly within large temple institutions, this tablet likely documented crucial information such as the allocation of rations or the movement and storage of goods. Each pictograph was carefully etched onto the clay surface using a sharp instrument, demonstrating the meticulousness and precision required in these administrative tasks. This artifact not only represents an important piece of history but also highlights the significance placed on effective administration even in ancient civilizations.