The intangible, universal vision of human rights held by the former justice minister permeated his writings and opinions until the end of his life.

He died in Paris on February 9th, at 95 years of age.

Robert Badinter, the president of the Constitutional Council at his home in May 1992, Paris, France.

9 February 2024 — The commander is dead. The thin old gentleman, whose time-worn figure could have been blown away by a gust of wind, for many years walked slowly, between two conferences, down the paths of his beloved Luxembourg garden, which unfolded beneath the windows of his beautiful Paris apartment. He used to take a short break there to buy a piece of licorice, of which he was very fond of and which was served to him with respect.

The austere Robert Badinter, wearing the armor of the law and a high idea of his mission, softened with age, submerged in memories and countless readings, and walked in the footsteps of his familiar shadows, Condorcet and Fabre d’Eglantine, a stone’s throw from the Sénat where he held a seat and whose intricacies he knew very well. Badinter, who will always be remembered as the man who abolished the death penalty in France, died in Paris during the night of February 9, at 95 years of age.

‘An intellectual in politics’

Badinter, born on March 30, 1928, in Paris, was a Jansenist from the upper bourgeoisie; he was also “republican, secular and Jewish” and not always easy to get along with, and one of the most hated ministers of his generation. With the dust of time settled, he remains the incarnation of a kind of integrity that belonged to the left that the test of power could not divert from its ideals. He spent 30 years as a lawyer, almost five years as justice minister, nine years as president of the Constitutional Council, and 16 years as a senator. He was criticized, not without reason, for having worked for a long time at sculpting his own statue, but he never stopped serving as a conscience. He was “an intellectual in politics,” walking in the footsteps of Nicolas de Condorcet, whose fervent biographer he was with his wife, Elisabeth.

On the evening of February 9, 1943, young Robert entered the building in Lyon where his parents, Charlotte and Simon, had gone to flee the German occupation of the northern half of France. But the Germans were already there. Klaus Barbie, the head of the Gestapo in Lyon, had signed the family’s deportation order a few hours earlier. The young man understood immediately, ran down the stairs and melted into the night. Simon, his father, was deported and would never return from the Sobibor extermination camp. Born in Bessarabia, in present-day Moldova, which was then under the Tsarist boot, he had fled the pogroms and then the Bolsheviks in 1919. For him, “a poor, Jewish, revolutionary student,” his son wrote in 2007, “France and the Republic were one and the same, mingling the Revolution, the emancipation of the Jews, human rights, Victor Hugo and Zola.

Until 1940, the Badinter family marveled at the extent of the freedom that was offered France, the first country to recognize the equal rights and conditions of Jews in 1791. “You could be a civil servant, an officer, a judge, when it was inconceivable elsewhere,” Badinter pointed out. Louis XVI’s sister expressed this in a sublime manner when she said, “The Assembly has put the last nail in the coffin of its follies, it has made citizens of the Jews.” Badinter often repeated the words of Emmanuel Levinas’ father, a Lithuanian rabbi, who, at the time of the Dreyfus affair said, “A country where they tear each other to shreds over a little Jewish captain is a country where one must go.” The lawyer judged that “this was a great way of seeing the Dreyfus affair: looking at the bright side, while half the population was devouring the Jews. Levinas always laughed when he said that, but it is profoundly true and, for men like my father, the French Republic was sacred.”

The family was viscerally French and patriotic. They talked politics at home. Simon Badinter was a socialist, he took his son 8-year-old son Robert – sitting on his shoulders – to listen to Léon Blum during the Popular Front left-wing coalition that governed France between 1936 and 1938. Simon “spoke French perfectly,” said his son, but it was a very literary French, very imbued with old turns of phrase, he spoke a language of the 18th century, which was very chastened, very polite.” Robert’s mother, “a very beautiful woman,” came from Bessarabia, like his father. The two met in 1920 in an unlikely “dance for the Bessarabians in Paris,” which always stunned their son: “It’s incredible that they met there, when they were born 60 kilometers away from each other in a corner of tsarist Russia!”

In 1943, the boy was not yet 15 years old. His other grandmother was deported to Auschwitz, then his uncle, his father, “and I don’t know the number of my cousins,” said the old man gravely. “You know, many of my people are on the wall of the Holocaust Memorial.” As a young man, he “did not even understand what it meant” to be Jewish, he said in 2018. “It’s part of my being. I am French, French Jewish, it is inseparable. It’s not a word, it’s a lived reality, I lived through the entire Occupation.”

A police commissioner gave false identity cards to Robert, his brother and his mother, and the three of them hid in Cognin, an Alpine village that welcomed and protected them. “In those terrible hours, that village was for me France,” he later said. “I am convinced everyone knew. Nobody ever said anything. All it took was for one word to get to Touvier and we were dead. Paul Touvier and his militia were in Chambéry, 4 kilometers from us.” After the Touvier trial, in 1994, Badinter, who was then president of the Conseil Constitutionnel, called the mayor of Cognin to tell him that he wished to return to the village. “To tell the story. Because I always thought it was very important for children to know that their parents are good people. With such a conviction, a child is better equipped in life.” Badinter bought them a Directoire-style “Declaration of the Rights of Man” and signed the back with all his titles. “The mayor was there and I found girlfriends, buddies, who were all, unfortunately, old like me, we fell into each other’s arms. ‘Ah, Yvette! Ah, Robert!’ It was divine, we had dinner, it was June, the weather was so nice.” He was made an honorary Cogneraud, a citizen of Cognin, and he was more than a little proud of this.

A deep-rooted sense of injustice

He never wore the yellow star; the family had already left when the order to wear the star was published in the occupied zone. In Lyon, it was not enforced and the Badinter family subsequently changed their identity. He first encountered the judicial system at the Lycée Vaugelas in Chambéry. One of his teachers, a member of the militia, was sentenced to death in 1944 (he was eventually pardoned). Badinter hated the man who had been in the militia, but he admired the teacher and discovered that, during the Liberation, justice, first and foremost resembled revenge. The episode anchored the feeling of injustice in him very deeply.

At the end of the war, as he watched the news and saw the state of those leaving the camps, understood that his father would not return. “I said to my brother: ‘Above all, don’t let mom go to the movies, try to make sure…’ (she went, of course, with a cousin), because I immediately said to myself ‘My father is not an athlete, he could never have held on for two years,’ it was just impossible. “

In spite of everything, he and his brother went to the Lutetia, the Parisian hotel where the deportees were gathered. “Absence is so obsessive,” Badinter explained. “It’s a very strange thing, it’s a constant fact of being human, as long as you haven’t seen your parent dead, it remains an idea, a concept, a pain. But mourning is impossible. For a long time, I dreamed that my father would turn up.” Back in Paris, the Badinter apartment was occupied by a collaborator, who refused to give up the place. The trial lasted a year, the young man heard “despicable remarks” about his family and did not get the place back until 1947.

A brilliant student, a hard worker (and an unapologetic ladies’ man), Badinter studied sociology and obtained a one-year scholarship to Columbia University, where he met Dwight D. Eisenhower, the future president of the United States. He did voiceover work for actors who were supposed to have a French accent in order to earn a few bucks, and discovered the weight of the law in American society and the firm shield it offers against the excesses of power.

In Paris, he enrolled in law school, and obtained his doctorate in 1952. The young man never forgot his father’s orders. “Real life, the only life, was the life of the mind, which is so profound in Judaism, it is the preeminence given to study, to intellectual rewards. The real revenge on prejudice and ignorance was knowledge. It is the only thing that liberates. For men like my father, knowledge and understanding were essential.” Moreover, the young Badinter easily pictured himself as a university professor. Teaching for him was “an eternal pleasure,” he would do it all his life.

Photo taken January 18, 1977 of Patrick Henry (glasses) in the box of the accused, and his defender Me Robert Badinter (foreground). In 1976 he killed 8-year old Philippe Bertrand, a child, and was sentenced to life imprisonment, evading the guillotine. The death penalty was abolished when Badinter became Minister of Justice.

His most vivid memory went back to 1977, the day after the Troyes verdict, where he had saved the skin of Patrick Henry, who was guilty of kidnapping and killing a 8-year-old boy. As he had for the last three years, Badinter entered the amphitheater at the Sorbonne. All the students were standing and they applauded him for a long time. On the blackboard, someone had written, “Thank you, Mr. Badinter.” The professor opened his briefcase and said: “Thank you. He was lucky. So am I.” And he calmly began his lecture.

A chance entrance to the world of law

In 1950, at 22 years old, he passed the certificate of aptitude for the profession of lawyer and entered the world of law, “by chance, not by vocation.” He started out modestly in a lawyer’s office, where his job was writing false letters containing break-ups or insults, intended to be used in divorce cases. This was his initiation into what he called “the judicial comedy” and he took a certain pleasure in his role as “a lawyer’s assistant.” This was when he met Henry Torrès, a formidable baron of the criminal bar, whose voice was “bronze,” whose stature was “powerful” stature and whose eloquence was “sublime.” Torrès later said that he had never met such an insolent young man, but Badinter was under the spell and very quickly came to call him “my master.” “He’s in his element in a storm,” said Senator Gaston Monnerville about the master. “When Henry Torrès argues, he’s like a gigantic lumberjack cutting down the forest.”

A writer, journalist and lawmaker, Torrès was an old-fashioned lawyer, who both fascinated and irritated Badinter; the young disciple was wary of his conventional eloquence, which sometimes seemed “heavy, old-fashioned, almost old-fashioned” to him. His style was assertive, it belonged to a new generation that used sober, effective rhetoric, and was supported by an in-depth understanding of the files. Georges Kiejman was of the same caliber, as was Jean-Denis Bredin. And when Torrès gave up the job in 1956, Badinter had to find clients. His colleagues, who found him cold and distant, do not care for him very much. (Tt was true that he didn’t often say hello to them.) But he had the good fortune to meet Jules Dassin, an American filmmaker who had fled McCarthyism. The director had a problem, but no money, Badinter had talent, but no clients: They immediately came to an agreement. And the lawyer soon prospered in copyright law, then found partners and set up an up-to-date firm where he defended the interests of Charlie Chaplin, Brigitte Bardot, Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Sylvie Vartan, Coco Chanel, and Raquel Welch who were followed by the magazine L’Express and the publisher Fayard.

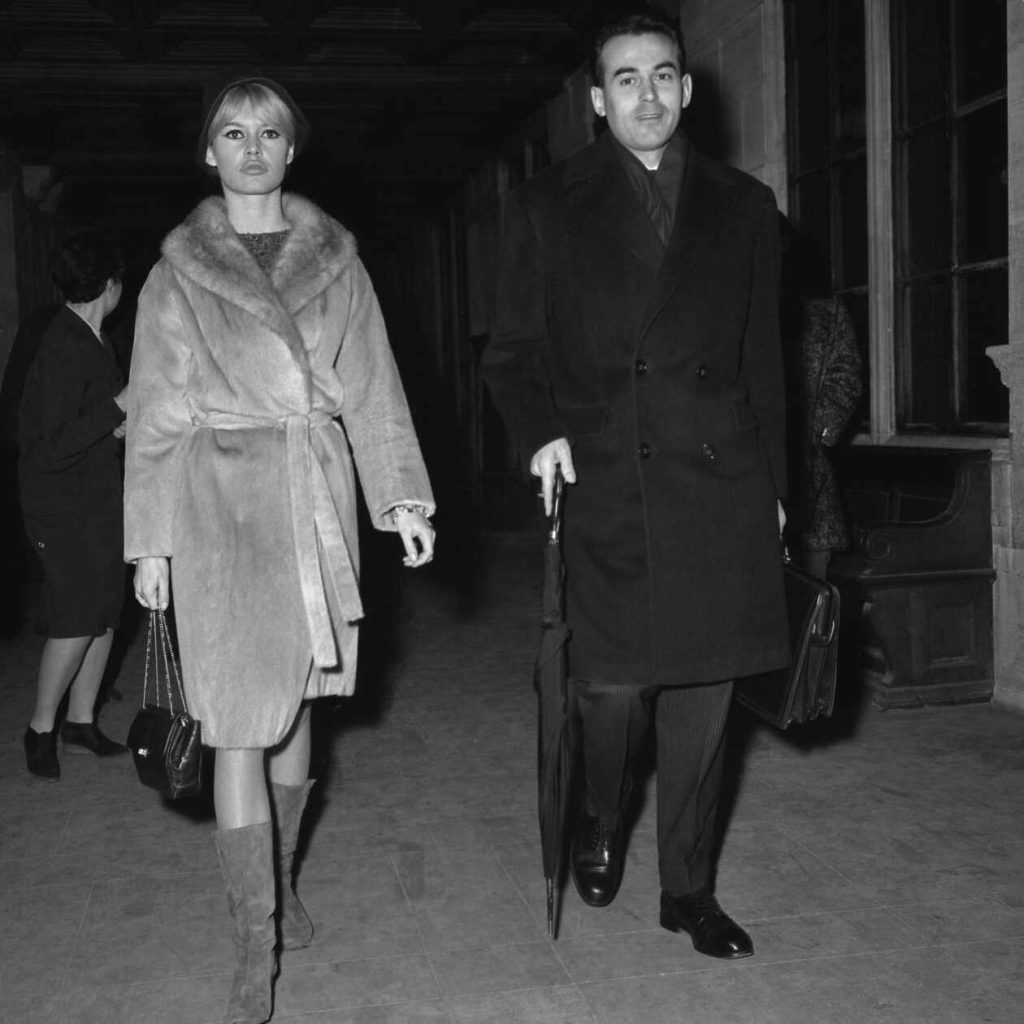

French actress Brigitte Bardot goes to the Palais de Justice of Paris accompanied by her lawyer Robert Badinter, on November 21, 1962, concerning the action taken by the actor Sami Frey against the Parisian weekly.

In 1955 the young litigator married a pretty actress, known as Anne Vernon, but whose real name was Edith Vignaud. She played the role of the mother of Geneviève (Catherine Deneuve) in Les parapluies de Cherbourg (The Umbrellas of Cherbourg). He divorced her and in 1966 remarried the writer Elisabeth Bleustein-Blanchet. They had three children – including one named Simon.

Bredin, a young man who was ‘too well brought up’

In 1966, Badinter joined forces with Jean-Denis Bredin, the first secretary of the Conférence du Stage (a highly respected prize for eloquence at the bar). They both founded a very successful business law firm, with Badinter taking charge of press law, copyright law and corporate law, and Bredin of inheritance and arbitration cases. The firm did not practice criminal law. The two men, both university professors, got along very well and had little in common. Badinter, always filled with a holy passion, was seen as a competitive adventure in the halls of justice, while Bredin was a young man who was “too well brought up,” as he titled his memoir, in which he portrays himself as an exquisitely courteous, refined dilettante. On the day the luscious Raquel Welch came to the firm, Bredin did not dare to talk about money, but Badinter took care of it without beating about the bush, not yet having the image of being a frugal Jansenist as he does today.

Along with Bernard Jouanneau, he was also brought in to defend François Mitterrand, leader of the Parti Socialiste (PS), who was being sued for defamation by Charles de Gaulle’s nephew, who reproached him for somewhat sharp comments on the Resistance in L’Expansion. Pierre Lazareff, the omnipotent boss of the newspaper France-Soir, introduced them to each other. The hearing took place on February 19, 1973, in other words, before the first round of the legislative elections on March 4. Mitterrand risked being stripped of his civil rights for one to three years. Badinter played for time and spent hours developing a treasure trove of legal arguments. “You won’t wear us down,” the judge warned him, but he managed to get the trial postponed. “A scoundrel’s tactics,” complained the judge. Although Mitterrand was ultimately found guilty, it was after the elections. Required to pay damages, he congratulated the young man on having “stopped the judicial machine.”

Badinter became close to former prime minister Pierre Mendès France, a photo of whom was still watching over him 30 years later in his office as minister of justice. But he was not a member of the circle of close friends with whom Mitterrand launched the renewal of the left. More personal than political, their relationship became closer later. In 1984, the Mitterrand, then president, asked Badinter to countersign, in the greatest secrecy, the act by which he recognized his illegitimate daughter, Mazarine Pingeot.

Amnesty International and the League of Human Rights

The lawyer was not interested in political games and apparatus maneuvers, even if it was sometimes necessary to bow to them. He was an unsuccessful candidate in the 1967 legislative elections in Paris, and he didn’t run again. The years that followed saw the founding of the Parti Socialiste, which would obtain a resounding electoral victory in 1981. Badinter was more at ease in the ranks of Amnesty International and the League of Human Rights. This did not make his link to Mitterrand any weaker. He had the ear of the first secretary of the PS as he would have that of the president, to whom he recommended, in the 1970s, a promising young man named Laurent Fabius, who would become prime minister.

At that time, Robert Badinter, a lawyer, had two faces. The first was the discreet face of a specialist in business law, the second was the flamboyant face of a defender of famous cases. He assisted the families of Judge François Renaud, who was assassinated in Lyon in 1975, and Jean de Broglie, former minister under de Gaulle, who was assassinated under mysterious conditions in Paris in 1976. He also defended André Resampa, former vice-president of the government of Madagascar, who was prosecuted in his country for treason; Klaus Croissant, the lawyer of the Baader gang; Ali Bhutto, the former Pakistani prime minister, who was hanged in 1979; and the socialist trade unionist Edmond Maire, who was accused by the Communist Party of having “pacified Algeria with a flamethrower.” The lawyer of politicians was also, on occasion, the lawyer of great criminals. He gained a reputation as the official defender of thugs and his most bitter opponents would shamelessly bring this up when he was appointed minister of justice.

However, Badinter was first and foremost a business lawyer. In his entire career, he only argued in court 20 times, seven times in capital punishment cases in France, and two abroad. But he had a certain understanding of justice, and refined his criticism of the judicial institution following the Algerian war; he was also a determined opponent of the death penalty, having made the fight a personal matter. But this came with risks – 1976 a bomb exploded on the doorstep of his apartment – and even in his own office, some found it difficult to understand why he defended murderers. “Defending,” said Badinter, “means loving to defend, not loving those we defend.”

In L’Exécution (“The Execution,” 1973), a terrible account and a bedside book for generations of lawyers, he told what it was like to defend Roger Bontems, who was sentenced to death in June 1972 in Troyes by a criminal court for complicity in the murders of a guard and a nurse after a hostage-taking at the Clairvaux prison. He had promised his client: “You will get out of this, Bontems.” “Are you sure?” “Absolutely.” He swore to him that the president would pardon him. Bontems was not the one who had killed, it was Claude Buffet, the other hostage taker. But President Georges Pompidou refused to be swayed and grant a pardon. One early morning in November 1972, Bontems was taken to the guillotine after a last glass of cognac. Badinter was there, in the cold courtyard of the Santé prison. He never forgot “the sharp slap of the blade against the buffer.” Neither would his readers. On the other hand, he did somewhat forget his co-defender, the excellent Philippe Lemaire, who is reduced in the book to the simple role of co-worker and who held a grudge for a long time. Badinter wanted people to know that the fight to abolish the death penalty was personal.

This failure made him the man who went on a crusade. The preface he wrote in 1989 to Victor Hugo’s Dernier Jour d’un Condamné (Last Day of a Condemned Man) showed to what extent he mixed the fight of those years with that of the writer. “A tireless fighter, he fought against the death penalty in Parliament as well as in the trial courts, in writing as well as orally,” an exact portrait. In 1977, in the same courtroom in Troyes, Badinter saved Patrick Henry’s head, when he was on trial for the kidnapping and murder of a child. The man, who, in front of the Parisian civil courts, displayed the cold eloquence of a jurist who was sure of his art, became a passionate spokesperson in the criminal courts, making the court and the jurors tremble. On that day, he delivered a defense speech that the day’s witnesses would not soon forget – and of which no written record remains, given that Badinter did not write down his speeches. He defended and saved the heads of six convicts. “They will be my witnesses when I appear before the Lord,” smiled the old man. “I am a modest sinner, like everyone else, but I have witnesses for the defense, although, for the most part, they are murderers.”

The end of the death penalty

Henry’s life sentence did not make up for Bontems’ execution. The road was still long until that day in the fall of 1981 when Badinter finally spoke the words of deliverance from the podium of the Assemblée Nationale before a sparse audience: “I have the honor, on behalf of the government of the Republic, to ask the Assemblée Nationale to abolish the death penalty in France.” On October 10, 1981, law no 81-908, appeared in the Official Journal. Dated the day before, its first article soberly declared, “The death penalty is abolished.” At the time, there were seven death row inmates in French prisons, whose lives were saved.

The old man kept a large black leather notebook, the original text of the law, flanked by a huge seal and hanging from a thin tricolor ribbon. “I wrote the first article, ‘the death penalty is abolished,’ with my own hand, with so much satisfaction,” Badinter said, at 88 years old. We could stop there. All the rest is uninteresting. The following articles serve to remove from the penal code the reference to a punishment that no longer exists. The text is short and the signatures take a whole page. “You will notice, unfortunately, that there is only one survivor left,” said Badinter, in 2016, referring to the artisans of the abolition. “All the others are gone. I am the only one left.” President Mitterrand, Interior Minister Gaston Defferre, and Defense Minister Charles Hernu all died before him.