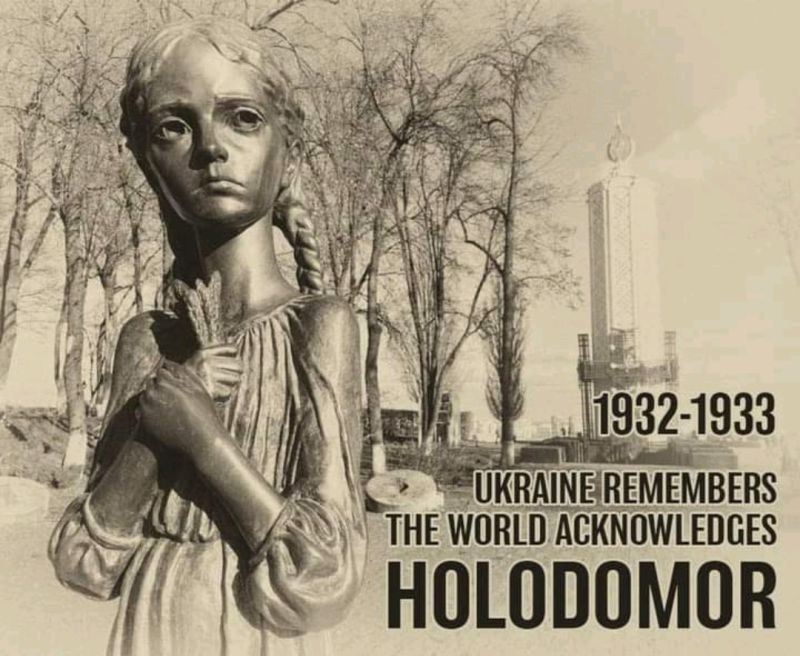

ABOVE: the statue of a little girl entitled “Girl with Ears of Grain” is in Kyiv and symbolizes the memory of 3.5 million children killed by starvation during the famine genocide of the Ukrainian nation in 1932–1933, an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people engineered by the Soviet government to destroy Ukraine politically and socially.

25 November 2023 – Today Ukraine commemorates the 90th anniversary of the Holodomor of 1932-1933, an event commemorated on the 4th Saturday of every November. And Russia has also decided to commemorate this day by launching a record number of Iranian drones into Ukraine, following the good tradition of the Soviet Union – the genocide of Ukrainian people. Just the cycle of Moscow’s impunity which will go unpunished.

Arguments over land take many forms in many places and have been going on for many centuries. One of the more poignant in recent times (the current Ukraine War notwithstanding) involves the violent intersection of a dispute involving vast tracts of territory – millions of broad acres of exceptionally fertile land in central Europe – with the craft of journalism. And in particular with one young British journalist who in the spring of 1933 discovered something terribly wrong, a crime of unfathomable proportions that was then unfolding in the central plains – yet again – of Ukraine.

His name was Gareth Jones, and he was born in 1905 in South Wales, the son of a local schoolmaster. He died on the eve of his thirtieth birthday, far away from home in western Manchuria. He had been murdered, shot three times in the head, by Chinese agents working for the NKVD, the Soviet Union’s much feared domestic secret police.

He was murdered in retaliation for a series of newspaper eyewitness reports that he had written two years before, in which he bluntly accused the Soviet Union of confiscating vast tracts of arable land in the center of Ukraine, and in the process starving millions of people, creating a genocide of near unparalleled ferocity and longevity. Gareth Jones has been named a hero in today’s Ukraine, and there are statues in his honor and any number of plaques and memorials, as well as a Hollywood movie.

What made his dramatic and terrible report, which was first published in a London newspaper, the Evening Standard, on Friday, 31 March 1933, of such monumental and lasting importance was its immediate denunciation – but not a repudiation by the Soviet authorities, who one might think had ample reason to refute suggestions that their policies were spawning a widespread famine in their southern provinces. Instead, the rebuttal was issued by Walter Duranty, a journalist for The New York Times, a native Briton born in Liverpool and who for the eleven years previously had been based in Moscow. He was a well connected figure of considerable influence, eminence and power, and he had already won a Pulitzer Prize for his extensive assessment – in a groundbreaking, multipart series – of the social and political effects of the Bolshevik revolution. And as was later revealed, in the employ of the Soviet government.

The tragedy that was reported by Gareth Jones – not a whisper of which made it into any of Duranty’s initial reporting – turned out to be wholly true, and when fully confirmed, it shocked the world. Ten million peasants had been starved to death, maybe more. The unfolding events of 1932 and 1933 in Ukraine are regarded by most today as a classic case of a genocide, and of a genocide far greater in number than any other in properly recorded modern history.

The event is now known in Ukraine and beyond as “the Holodomor” – murder by starvation. It is now known to have been the result of a Stalinist policy madness born of a tyrannical and ideologically driven desire in Moscow to have the land taken away from the ordinary peasantry of Ukraine, for it to be turned into great collectivised and industrialised farms, which would be established in a way that would be entirely consonant with the Marxist ideal of public ownership – and to cover-up a disastrous planning decision by Moscow who needed to blame somebody other than itself.

The policy instead created a human disaster of unimaginable proportions, and Gareth Jones – though he would soon thereafter pay the ultimate price for its exposure – was the first to reveal it to the world. His first revelation appeared – not under his own byline, but under that of another Pulitzer Prize winner, H. R. Knickerbocker, who had listened to Jones at a press conference he held in Berlin on his return from his surreptitious expedition to the Ukraine – as the lead in the New York Post of Wednesday, 9 March 1933. The headline was stark: “FAMINE GRIPS RUSSIA, MILLIONS DYING … SAYS BRITON”. The story was picked up by a host of other newspapers the next day, and on the day after that, Friday, Jones was able to publish his own piece in the Standard:

All that is best in Russia has disappeared. The main result of the Five Year Plan has been the tragic ruin of Russian agriculture. This ruin I saw in its grim reality. I tramped through a number of villages in the snow of March.

I saw children with swollen bellies. I slept in peasants’ huts, sometimes nine of us in one room. I talked to every peasant I met, and the general conclusion I draw is that the present state of Russian agriculture is already catastrophic, but that in a year’s time its condition will have worsened tenfold.

If it is grave now, and if millions are dying in the villages, as they are, for I did not visit a single village where many had not died, what will it be like in a month’s time? The potatoes left are being counted one by one, but in so many homes the potatoes have long run out. The beet, once used as cattle fodder, may run out in many huts before the new food comes in June, July and August, and many have not even beet.

‘Have you potatoes?’ I asked. Every peasant I asked nodded negatively with sadness.

‘What about your cows?’ was my next question. To the Russian peasant the cow means wealth, food and happiness. It is almost the center-point upon which his life gravitates.

‘The cattle have nearly all died. How can we feed the cattle when we have only fodder to eat ourselves?’

Walter Duranty made a hurried reply which appeared in The New York Times, and under the less than reassuring headline “RUSSIANS HUNGRY, BUT NOT STARVING”. He refers to the Ukraine situation in his piece, cabled from Moscow in response to Jones’s Berlin news conference of a few days before, clearly having been pressed into service by his foreign editor (and the Soviets we would later find out), who must have been stung by the jeremiads in the competing Manhattan papers.

Somewhat wearily, Duranty describes Jones as a man “of a keen and active mind” who had “taken the trouble to learn Russian, which he speaks with considerable fluency” but then he goes on to denounce the Welsh journalist in tones of patrician superciliousness. He felt, he said, that Jones’s judgment was “somewhat hasty” and was based on “a forty-mile walk through the villages in the neighborhood of Kharkov, a totally inadequate cross-section of such a big country – and nothing could shake his conviction of impending countrywide doom”.

A photograph of Duranty taken around this time shows him and two contented-looking guests dining comfortably in his Moscow flat, attended by a servant with an uncanny resemblance to the young Trotsky pouring a glass of red wine. The table is set with candles, silverware and fine napery. The dinner plate in front of the photographer’s seat appears loaded with food. In the image the diners may well have been hungry, but most certainly were not starving, nor probably ever had been. Duranty was prolific, and the articles he wrote during the next few days kept to the theme of good harvest and prosperity.

But Duranty’s reputation began to suffer. Malcolm Muggeridge, who had begun his own vivid investigation, declared Duranty to be the “greatest liar” he had ever known, Joseph Alsop, the celebrated mid-century American syndicated columnist, said that “lying has become Duranty’s stock-in-trade”.

NOTE: all of this eventually persuaded The New York Times in 1990 to break rank with their long dead correspondent’s official reputation. The newspaper denounced him publicly and decried his reporting from Moscow sixty years before as “some of the worst reporting to appear in this newspaper”. The storm led to a move to strip Duranty, posthumously, of his Pulitzer. But the Pulitzer board, both in 1990 and then again after a further Times appeal in 2003, declined to revoke the award. “There was no evidence”, the Pulitzer board said … in a masterly piece of pusillanimous evasion. All despite mountains of evidence from former journalistic colleagues, from intelligence agencies, and even from the FBI that Duranty had known perfectly well that what he was writing was only vaguely concealed Kremlin propaganda, that his deception had been deliberate, and he was on the Soviet dole.

What Gareth Jones discovered – and really did discover – during his “forty-mile walk through the villages” was the appalling practical consequence of an act of Kremlin policy that had been hammered out in the spring of 1929 and which was targeted unequivocally at both the peasantry who worked the fields in the country’s southern agricultural belt and the land that they owned. The stated intention of this policy was to destroy one specific component of the USSR’s peasant class, and to wrest their land away from them wholesale, confiscating it and turning it over, in immense quantities, to the ownership of the state.

Stalin’s so-called Five Year Plan, the first of several such economic stimulus programs bent on promoting massive changes to the new country’s industrial and agricultural sectors, went into formal practical effect in October 1928. Within six months before the plan’s details had even been completed it was shown to be a complete disaster, both hastily and shoddily contrived, and so not surprisingly turned out to be a massive debacle. But somebody had to be blamed and hard currency was needed to prop up the government. And so we learn of a Soviet party official, Sergey Syrtsov, who said it was the Soviet people to whom we blame for the shambles, especially the Ukrainians.

And the damnable word that Syrtsov uttered to describe them was kulak, which in literal translation, and in its Turkish etymology, means “fist”. A kulak in the Soviet Communist lexicon was a tight-fisted person – a relatively prosperous man of the countryside who owned a small amount of land and who made a modest profit from it. But they were “parasites” in the eyes of the revolutionaries, and of whom there were millions in the immensely wide grain-growing regions of the southern and eastern Soviet Union – Ukraine. They had been identified as the most verminous creatures in the population of the USSR. They were a class of people worthy of utter public contempt, just as were the greasiest of landlords and the greediest of capitalists. And must be destroyed and their lands seized.

I can recommend scores of books and articles I have read that go into the brutal details of how the Soviets executed this famine genocide. It is a horror story.

But I’ll point you to a fabulous multi-media web site called “Ukrainer” which puts all of this in perspective: witness statements, a debunking of the myths and common lies of the Holodomor, details on these crimes committed against humanity, how the Holodomor influences Ukraine today, etc., etc. To access the site please click here.

“Death solves all problems. No humans, no problem.” – – Joseph Stalin