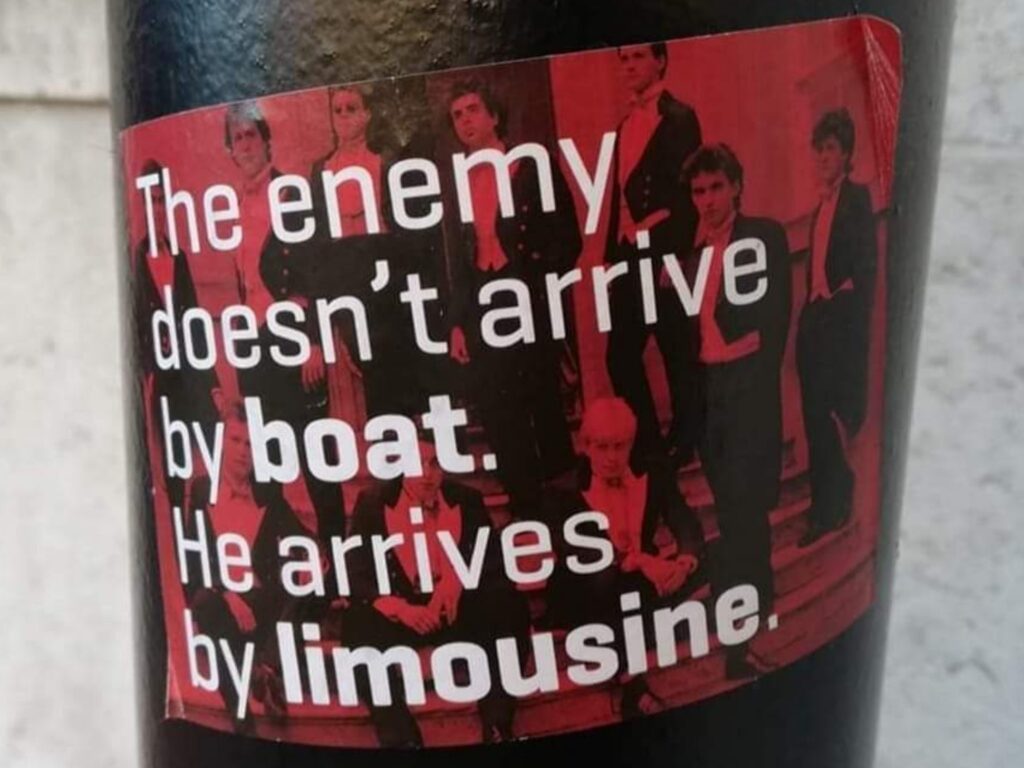

Forget the lonely teens in hoodies, says security expert Bruce Schneier – it’s the rich and powerful who undermine the rules

“When it comes to finance and politics, hackers come dressed in business attire,” writes Schneier

18 February 2023 – In this weekend’s edition of The New York Times Sunday edition (out now) there is an Op-Ed by David Miliband, the former foreign secretary of the United Kingdom. It’s about impunity – the current mind-set that laws and norms are for suckers. He writes:

“Impunity is the exercise of power without accountability, which becomes, in starkest form, the commission of crimes without punishment. In Ukraine this goes beyond the original invasion. It has included repeated violations of international humanitarian law, which is supposed to establish clear protections for civilians, aid workers and civilian infrastructure in conflict zones every day. The danger is that few people will ever face consequences for these crimes.

The impunity in Ukraine is only one part of a broader global trend. In conflicts around the world, attacks on health facilities have increased by 90 percent in the past five years, and twice as many aid workers have been killed in the last decade as in the one before that. In recent years, civilians account for 84 percent of war casualties — a 22-percentage point increase from the Cold War period.

The lack of accountability for crimes in places like Syria and Yemen has fueled the culture of impunity we now see in Ukraine and elsewhere.

It’s not just war zones. Impunity is a helpful lens through which to understand the global drift to polycrisis, from climate change to the weakening of democracy. When billionaires evade taxes, oil companies misrepresent the severity of the climate crisis, elected politicians subvert the judiciary and human rights are rolled back, you see impunity in action. Impunity is the mind-set that laws and norms are for suckers”.

It ties in nicely with a new book out by Bruce Schneier, the well-known security expert, who turns his gaze to the increasingly vulnerable financial, legal and political systems that underpin society:

“When most people look at a system, they focus on how it works. When security technologists look at the same system, they can’t help but focus on how it can be made to fail”.

NOTE TO READERS: I have been a big fan of Schneier ever since he coined the phrase “security theatre” to describe the bullshit, convoluted, serendipitous and often pointless security processes we’re all subject to in airports, etc.

Failure here does not mean malfunction, but rather the subversion of the system’s intended goal. An ordinary person sees an ATM as somewhere to withdraw cash. A hacker sees it as “just a computer with money inside”. The aim of his book (“A Hacker’s Mind”) is to show us how thinking like a hacker can help us re-evaluate modern problems of regulation and enforcement, and make sense of a world where rules increasingly feel made to be broken.

NOTE TO READERS: if you subscribe to Schneier’s blog, a lot of this material will be familiar. If you do not, the book puts it all together very nicely.

But first, we must update our understanding of what a hacker looks like. Even if the cliché of the lonely teenager cranking out code into the night ever held any truth, when it comes to finance and politics, hackers come dressed in business attire. Schneier argues that it is the rich and powerful who hack financial and legal systems, finding ways to avoid taxation or undermine regulations designed to protect the rest of society. Although, quite frankly, its usually the rich and powerful in concert with the help of governments.

Seen through this lens, tax lawyers become “black hat” (malicious) hackers, poring over lines of regulation to find bugs and exploits that will profit their wealthy clients, such as the “Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich” tax avoidance strategy used by some of the world’s largest multinationals to squirrel away profits in tax havens.

A chapter on venture capital shows the hacking metaphor hard at work. Here Schneier focuses on multibillion-dollar investments made by SoftBank’s Vision Fund and others into persistently profitless gig economy companies such as Uber and Deliveroo. He argues that the approach damages both markets and the labor force, and that instead of picking winners, this kind of VC strategy creates conditions where companies cannot lose, in a way “that would be called communism if the government did it”.

Schneier’s fixes for these problems borrow from the lexicon of computer security. The fixes range from “red teaming” new tax laws — employing tax lawyers to eliminate loopholes before legislation gets passed, in hacker speak to switch their black hats for white hats — to helping regulators react faster when existing governance regimes are subverted, giving authorities the ability to issue the equivalent of “patches” to the rules.

So the old, classic question, has moved from “how do elites govern us?” but “how do elites succeed in evading our systems of governance?” Schneier describes a world in which “social and technical systems are evolving rapidly into battlefields of constant subversion and countersubversion”, and predicts a near future where this relentless undermining of trust has catastrophic results. It’s a hauntingly credible vision.

Computerisation has accelerated the pace and scale at which the wealthy can undermine the rules. Artificial intelligence may do much worse. Schneier invokes stock market flash crashes, as well as the distortion and fragmentation of public discourse by social media algorithms that silently tailor news feeds to individual bias, as portents of what is to come. In a recent interview promoting the book he said:

“Large-language models such as ChatGPT and Google’s LaMDA are trained on, among other things, the web, which is to say society’s sooty exhaust, carrying all the errors, mistakes, conspiracies, biases, bigotries, presumptions, and stupidities — as well as genius — of humanity online. It is a gift to the elites, supporting their underlying corruption in society’s soul”.

Humans are still better hackers than machines, and Schneier presents plenty of evidence to suggest that in the near future this will not change. For now, “while a world filled with AI hackers is still a science-fiction problem, it’s not a stupid science-fiction problem”. Schneier beseeches us to get our house in order before AI takes us to a point of no return.

In places, the hacking metaphor feels stretched thin. Schneier often bumps up against issues that feel both familiar and intractable: there’s exposition of the faults of the American legislative process that are neither new nor insightful. The metaphor only takes us so far, and Schneier is smart enough to realise that computer code and human-made law operate according to their own distinct logics. Yet occasionally the starkness and sheer bombast of his prose leave his analysis searching for a place to land.

With “A Hacker’s Mind”, Schneier joins other technology specialists who have turned their focus to problems in politics and markets — partly, one feels, out of exasperation at the failure of these structures to hold technological threats in check. Given the role of the computer paradigm in complicating corporate, legal and political life, it makes sense that a security expert should cast his net a little wider. “A Hacker’s Mind” may stop short of guiding us to the end of the tunnel, but I think you’ll find it sheds vital light on the beginnings of our journey into an increasingly complex world.