How America’s major newspapers have stumbled in covering a serious phenomenon

23 January 2023 – It is impossible in a column such as this to parse the morass of antisemitism in America. It is huge, it is complex. But it is vital that we see how the fundamental rhetoric that has propelled antisemitism over many centuries around the globe helps fuel the larger movement. This is about the “othering” of Americans. It is about dividing the country into “us” and “them”.

I do know the reality. I know that hate has always been a part of the human experience. But it has wreaked havoc across history, causing the pain, suffering, and death of countless people. It is fueled by seeing others as enemies rather than as fellow members of the human species. But antisemitism is one virulent manifestation of this “us vs. them” mindset. To survive and thrive, America must reject it in all of its forms.

And my issue is that I am gripped by history – and by the present day. By the war in Ukraine, and by the Holocaust. Anyone who researches the history of Jews who is not Jewish will sooner or later experience a moment of heart-stopping resonance as I have. As I noted before, when I was reading In the Midst of Civilised Europe about the pogroms of 1918-21 and the onset of the Holocaust, there was Ukraine on the map on the inside cover. Reading that book in 2022 made it impossible not to contemplate the significance of place. The Holocaust was a European phenomenon with many different starting points. Veidlinger has produced a riveting and nuanced account of developments in one very specific location: the area claimed by the Ukrainian People’s Republic in the aftermath of the First World War. [I have a postscript about the book below].

And writing and film producing about the Holocaust, about genocide, about antisemitism, I do so as a reader and as a “watcher”, not as a true scholar. And I readily admit I have read but a fraction of the Holocaust and genocide literature available in English, which is itself only a fraction of the literature available in Dutch, French, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Polish, Yiddish, and other languages.

But over the last 5+ years of research and video and film production my friends and colleagues have recommended an endless stream of sources plus their intimate experiences and knowledge. One such source is the magazine Jewish Currents which is the subject of this post. Well, actually Mari Cohen, the magazine’s assistant editor. In the current issue Mari writes:

At the end of last year, I was honored to be invited by Nieman Lab, a Harvard-based outlet that covers the media, to participate in their “Predictions for Journalism 2023,” in which they ask people from across the industry to offer short forecasts about where they think it’s headed. Topics range from how AI will change newsrooms to how reporters should approach right-wing politics. I was excited to share some of my thoughts on the state of antisemitism coverage with Nieman’s audience.

I sent in a little essay on the subject, but Nieman Lab never posted it. After an initial email telling me that my piece would be published soon, the editor stopped responding to the multiple follow-up messages that I sent over the course of several weeks. I still think my piece about how traditional journalistic practices perpetuate an incomplete—at times harmful—understanding of antisemitism is worth sharing. So we’re publishing it as today’s newsletter. Here it is, exactly as it was written in December 2022.

The following is that article:

AT THE START OF 2022, a gunman barged into a synagogue in Colleyville, Texas, and took four congregants hostage; at the end of the year, just last month, two men who allegedly planned to attack a synagogue were apprehended in New York City. This moment calls for a serious, rigorous exploration of the nature of antisemitism and how to fight it—and yet mainstream media coverage of antisemitism regularly fails to rise to the occasion. Articles about spiking antisemitism often contribute to an ahistorical fearmongering that is likely to only deepen Jewish communities’ anxiety and make it harder to accurately assess antisemitic threats. They tend to flatten a rich academic debate about the historical nature of anti-Jewish activity into clichéd descriptions of antisemitism as the “oldest hatred.” Differences between state-sponsored antisemitic policy and individual antisemitic actions are rarely elucidated. The most egregious coverage conflates Palestinian solidarity activism with antisemitism, equating, for example, politicians who have courted antisemitic white nationalists with those who have sought to restrict US funding for Israeli human rights abuses.

Journalists, of course, don’t come to this approach entirely on their own. They rely on a set of sources that encourage a particular perspective on antisemitism. Most articles on antisemitism in major publications cite the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), the century-old organization considered the central voice of American Jews on matters of persecution. Like any institution, however, the ADL is not a neutral arbiter but a political actor—one that from its early days worked to minimize the influence of radical and less-assimilated corners of American Jewry and forge a centrist, respectable community that could work hand-in-hand with the US government. Since the late 20th century, the ADL has served as an ardent advocate for the state of Israel, targeting critics of Israel, especially from communities of color, as zealously as it pursues neo-Nazis. Even setting aside its conflation of antisemitism and anti-Zionism, the ADL’s numbers cannot reliably be used to track changes in the prevalence of antisemitism over time, given that the organization regularly changes its reporting methodology—including, for its 2021 report, incorporating data from an entirely new group of sources. Yet the ADL buries the caveats about its numbers deep in its press releases and reports, instead employing its statistics to support claims of a shocking increase, an assertion that most news articles parrot as fact. That’s part of what leads to articles that claim that American antisemitism today is comparable to that of the 1930s and ’40s—despite compelling evidence that anti-Jewish sentiment and institutional discrimination were higher in the interwar period.

To understand why mainstream press coverage so frequently adopts the narrative of institutions like the ADL, it can be helpful to turn to the cultural theorist Stuart Hall, whose 1978 book Policing the Crisis (written with several collaborators) sought to understand how particular narratives about crime were perpetuated in British culture. Hall and his coauthors argued that the tight deadlines and culture of “objectivity” found in the newsroom led reporters to frequently turn to a particular set of easy-to-reach established voices—whom Hall calls “primary definers”—to serve as experts, resulting, in Hall’s words, in a “systematically structured over-accessing to the media of those in powerful and privileged institutional positions.” It’s easy to see how this operates in contemporary crime coverage, where law enforcement accounts tend to serve as the backbone of news reporting; similarly, in coverage of antisemitism, major organizations like the ADL—and often other Jewish groups with similar politics like the Jewish Federations of North America or American Jewish Committee—play the role of “primary definers.” Hall argues that while journalists often give “counter definers” who dissent from institutional interpretations a voice in their stories, such actors are forced to respond within the framework already laid out by the primary definers, and therefore, in a sense, have already lost the battle. For example, once the assumption has been established that anti-Zionism is antisemitism, advocates for Palestine are placed in the defensive position of insisting they are not antisemitic, rather than setting the terms of discussion about Israel’s treatment of Palestinians.

Subverting the structural manner by which journalism can reproduce hierarchies of power is no easy task. It’s a challenge I regularly confront in my own reporting, when turning to respected institutions often feels like the easiest way to establish credibility with my audience. Reporting on the issue of antisemitism, in particular, can feel like wading into a minefield: No one wants to risk appearing to minimize the danger of antisemitism, and given the history of pernicious antisemitic tropes about Jewish power, it can feel fraught to apply scrutiny to major Jewish institutions. And when the fight for liberation by one group (Palestinians) is frequently maligned as an act of hate towards another (Jews), the discourse can become intimidating to parse. But the stakes are high. Laws restricting Americans’ ability to boycott Israel, supported by many Jewish institutions in the name of fighting antisemitism, are now serving as templates for new statutes limiting the right to boycott all sorts of industries, from fossil fuel companies to gun manufacturers. Meanwhile, former President Trump sat down to dinner this month with antisemitic white nationalist Nick Fuentes and the Hitler-praising rapper formerly known as Kanye West—and has defended himself by citing his record of pro-Israel policymaking. Good journalism requires courage and a commitment to the truth in all its complexity. If reporters aren’t up for that, they should find another beat.

From “In the Midst of Civilized Europe” which I noted above:

In the years after the Holocaust, survivors began compiling memorial books, one for each city and town. These literary monuments to destroyed communities preserved local stories and documented the names of victims. But such memorial books are not only histories of the prewar period; they are also prehistories of the war itself.

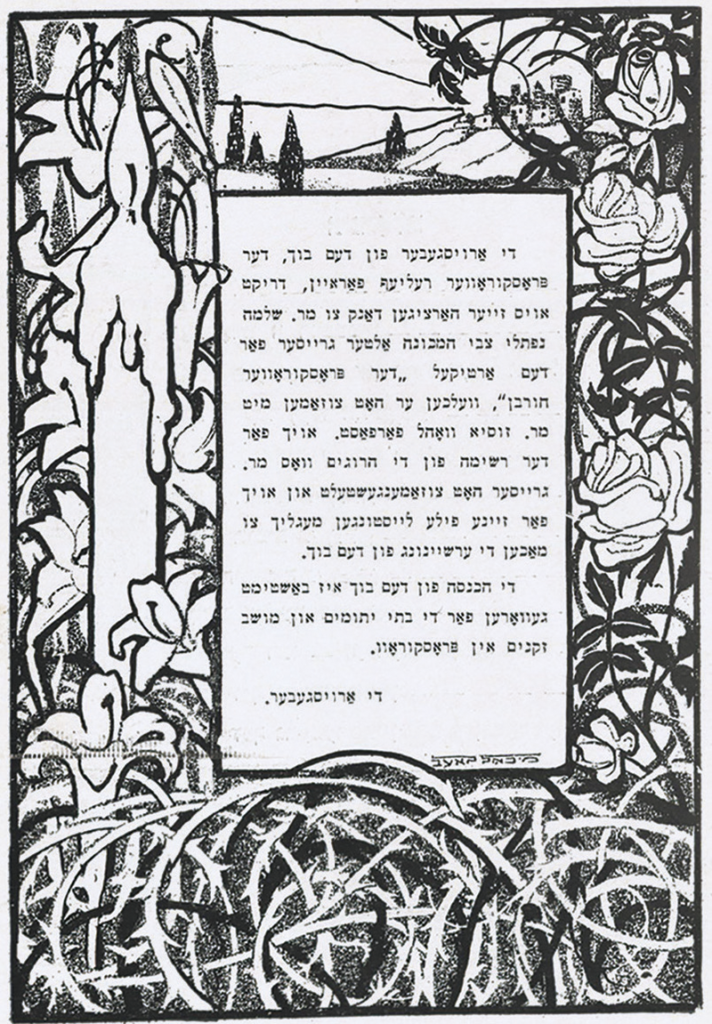

Take the newly discovered memorial book from the town of Proskuriv, in what is now Ukraine. The book, Khurbn Proskurov, whose cover is depicted above, captures the calamity the city endured. It concludes with the names of the martyred—a list that extends to thirty pages.

What differentiates Khurbn Proskurov is that it was written in 1924—nine years before Hitler’s rise to power and fifteen years before the start of the Second World War. It commemorates the real beginning of the Holocaust: on February 15, 1919, Ukrainian soldiers murdered a thousand Jewish civilians in what was at the time possibly the single deadliest episode of violence to befall the Jewish people in their long history of oppression.