The program is new, and still imperfect – and like all human-made projects likely will remain so, even after most of its kinks are worked out. But it uses new technology to help an age-old need to connect.

13 November 2022 (Washington, DC) – Over the last 5 years I have been involved in a film project that has been the most challenging of my career. It has been a deep dive into the political uses of dehumanisation, genocide and massacre, with a primary focus on the life of Jacques Semelin, one of the world’s leading authorities on these subjects. The project was delayed due to COVID, but during that time I had the opportunity to significantly expand it. And, obviously, the project changed due to the Ukraine War (how could it not?).

For more background on the project with links to the videos we’ve finished and some of the background stories click here.

On this trip to the U.S. I have spent more time at the U.S. Holocaust Museum which directly contributes to the following story. It is about a tool using artificial intelligence (AI) built by Daniel Patt, a software engineer for Google, and it could hold the key to putting names to some of the many faces, both victims and survivors, in hundreds of thousands of historic photographs. I was fortunate to be at the Museum on the day the BBC was filming a story about the project and I was allowed to tag along on their assignment. But, I should add, the Museum staff knew about my work and had given me filming rights on previous visits so it was not all that difficult for the BBC to acquiesce.

We’re used to seeing pictures taken of Jews before or during the Holocaust. Black and white photos, some grainy or ill-focused, others sharp and artful. Some of the older pictures show hopeful-looking children or happy family; as time goes by, the expressions becoming increasingly grim. By the end, they’re desperate-looking faces, staring out from a mass of other faces. We look at them, hope that they’re the pictures of the few who escaped, knowing that by definition most of them did not.

But in most cases we don’t know the names of the people in those photographs. If they’re not family heirlooms, preserved with names written on the back, the people in them became anonymous long ago, even as their faces haunt us. But technology often makes the seemingly impossible – retrieving names from the fog of unrecorded history – possible.

Of course, it’s complicated.

One of the seemingly impossible tasks that artificial intelligence can perform is facial recognition. That is, it can identify a person from an image; it can put a name on a flicker in a video. I have written about this in numerous posts and it is amazing.

SIDE NOTE: last week at one of the Pentagon cybersecurity sessions I saw how the Pentagon can identify which Russian generals are in the war zones in Ukraine. More on that later this week.

This AI is also highly controversial, as you well know. It can erode privacy, even when it works right, and it tends to be far less successful with people of color than with white people, and that’s resulted in many false identifications. It’s particularly dangerous when it gives law enforcement agencies incorrect results.

But in this case it can, with increasing accuracy, give the nameless back their names.

The project allows people to upload their photos. Then Numbers to Names, as Patt calls his project (his partner is Jed Limmer, a very close friend) will select 10 images from the archives to which is has access – mainly the archives of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, which has more than 34,000 photos, many of them with dozens of faces; last year I spend 2 days going through part of that archive – that are possible matches with the questioner’s uploaded images. Altogether, there are about 500,000 images that the project can search. That’s about two million faces.

The program is new, and still imperfect – and like all human-made projects likely will remain so, even after most of its kinks are worked out. But it uses new technology to help an age-old need to connect.

Patt thought of the project when he was at the Polin Museum in Warsaw in 2016. From an interview in The Jewish Standard:

“I was just overwhelmed by the feeling that I was looking at family photos. Three of my four grandparents were Holocaust survivors. I knew all of them. One, my 91-year-old grandmother, lives in Manhattan. I had the thought that if I left the museum, I would never see them again – those haunting photos, those faces, possibly of my lost family. I didn’t know if they were online”.

So software engineer that he is, he started thinking about technology, quickly moving from how to digitize them and make them accessible to the larger problem of how to identify the people in them. He talked to his long-time friend Jed Limmer – the two men met more than a decade ago when they both worked at a bank, but Limmer’s ancestors had left Europe long before the Holocaust.

Limmer has been on the boards of small nonprofits, so he had experience in the nonprofit space. He thought the idea was powerful, and he wanted to be involved in it.

They have been working with a huge number of photos from many Holocaust archives, taken by many photographers, for a range of reasons. There were really interesting photos taken by a Bulgarian photographer. He captured the Jews as they were being registered in Macedonia. Those photos, among the many that the project uses, are available online, along with many others on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s website. Many are terrifying, deeply sad images.

Plus, there is a trove of photographs taken by Nazis, some from the pre-Holocaust era, of people just living their lives. Limmer has said:

“I felt like when I was looking at those pictures, I was looking at myself. These weren’t people who lived hundreds of years ago. This was 80 years ago. I felt like there was something wrong with not working to identify them and sharing them with their descendants.

“The project got started in earnest in the last few years, pre-Covid. Our original plan was that people could go to a museum, there would be a private booth, and you could be photographed there. That photo would be uploaded immediately and then there would be a private experience, when the entire collection would be compared to your face, to see the pictures most similar to your own photo.”

Right now, not everyone who tries will find a face he or she recognizes, but if you are someone who has lost a relative in the Holocaust, or if you have a connection, there is a “reasonable chance” that you’ll be served that person’s photo. That reasonable chance is the key point of the project. It’s the best effort to find a photo of your family, but even if you don’t find it, it’s still worth trying.

People are most likely to be matched accurately with relatives who were about the same age in the photograph as the seeker is now. Some of the photos come with identifying information, others do not.

There are two ways to do the search. If you go to the website, numberstonames.org, you’ll see a button that says “Select and image”. If you do that, and hit search, you’ll get 10 results that are the most similar to the face in the photo you uploaded. You can get the results of a search of about 34,000 photos – that’s about 170,000 faces – in a couple of seconds. That’s the quick search.

The full search is accessible by going to the menu. You can sign up and create an account, and then you upload a photo. We run the search over a much larger set of photos – about 500,000 – and you get the results in about a day. It’s free to users.

Patt and and Limmer funded the site and the technology behind it with their own funds but now they are working with FJC, an organization that incubates innovative philanthropies. This project was a perfect match for them. They handle the infrastructure, taking the burden off Patt and Limmer.

And the number of searches has begun to rise dramatically. Right now, they are throwing a lot against the wall, to see what sticks. But they need to fundraise. There is a huge cost to what we are doing, and right now it is completely self-funded. My company, Luminative Media, is providing some funding.

The two men feel that they don’t have much time to spare. Patt recently noted:

“There is an urgency to it. My grandmother – who is very private and doesn’t want her name or any biographical details made public – was 9 at the beginning of the war. If any photographs of any of her relatives are to surface, it would be best should that happen soon.

We also want to partner with schools and universities. The search experience is something that is unforgettable. If you can match a photo with a name and a place and a family, you are potentially helping not only the descendant, and maybe even the survivor him or herself, but if there is nobody still alive, you are finding someone who had a life”.

Although the project is brand-new, there is one fairly well-known story its backers tell. The rocker Geddy Lee, from the band Rush, is the son of a Holocaust survivor, Mary Weinrib, who died last summer at 95. Numbers to Names was able to identity a photograph of Ms. Weinrib in a DP camp after she was liberated from Bergen-Belsen. Then, the technology helped Lee find more photos of his extended family in Yad Vashem’s collection. This brought in funding from various sources.

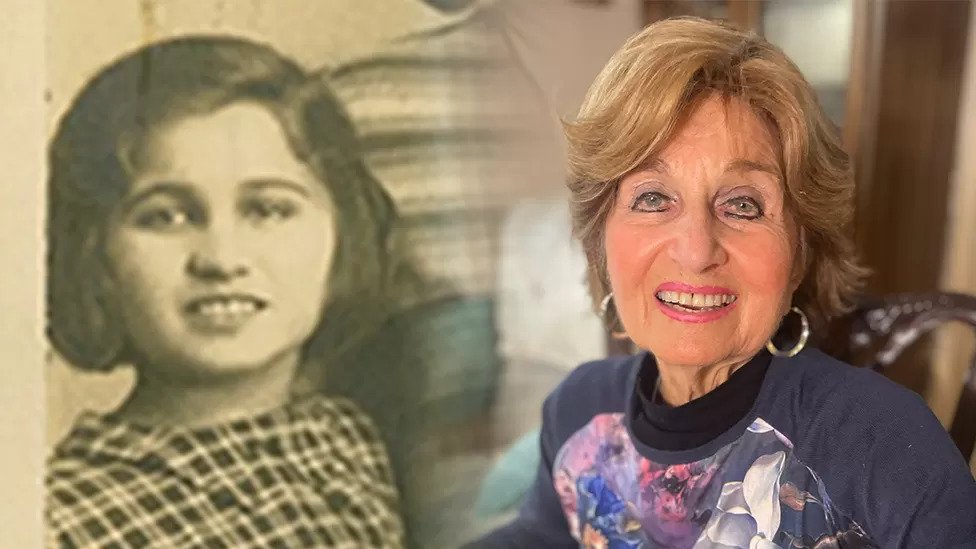

The BBC story followed Blanche Fixler

From the BBC report:

Blanche Fixler remembers hiding inside a bed while Nazis searched for her.

“I felt them tapping on the bed,” she recalls. “I said, you better not breathe or sneeze or anything – or you’ll be dead.”

Blanche was a survivor – she was lucky. Six million Jews like her were murdered by the Nazis in the Holocaust during World War Two. The names of more than one million of those people are unknown.

Now a tool using artificial intelligence (AI) – built by Daniel Patt, a software engineer for Google – could hold the key to putting names to some of the many faces, both victims and survivors, in hundreds of thousands of historic photographs. It found Blanche in a wartime photo which she had never seen before.

Daniel’s website, Numbers to Names, uses facial recognition technology to analyse a person’s face. It then searches through archive photos to find potential matches. The software has been cross-referencing millions of faces, to try to find matches for people who have already been identified in one photo – but not in others.

That detective work – joining the dots – could then help identify some people in photos whose identities are currently unknown.

Blanche, who is now 86 and lives in New York, knew about the family snapshot below on the right – but she had never previously seen the group photo on the left, which was taken in France during the war.

It was Daniel’s AI software which made the connection.

ABOVE: Blanche’s face in the archive photo on the left, was previously listed as unidentified – she knew about the family photo on the right

Blanche was known by the name Bronia as a child. She lived in Poland when the Nazis came looking for her and her family.

Her mother and her siblings were murdered – but she was saved, thanks to her Aunt Rose, who hid her.

Daniel travelled to meet Blanche to reunite her with the lost image from the past.

It triggered a long forgotten memory in her – a French song she learned as a child.

Blanche immediately recognised herself standing at the front of the large group of people, but that’s not all.

She also identified her Aunt Rose and one of the boys in the photo – giving Daniel and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum new information to work with.

“It’s so important to identify these photos,” says Scott Miller, director of curatorial affairs at the museum. “You’re restoring some semblance of dignity to them, some comfort to their family, and it’s a form of memorial for the entire Jewish community. That’s part of the problem. I can’t stress enough how important these photos are of individuals.

“We all know the figure – six million Jews were killed – but it’s really one person six million times. Every person has a name, every person has a face.”

ABOVE: Blanche is in the middle of the front line – previously only three people in this photo had been identified