“Modern military professionals talk of war’s nature as chameleon-like. A chameleon’s skin may change color to fit its surroundings, but it remains a chameleon. In contrast, war’s character—the institutions that participate in war, the weapons, the doctrines, and indeed the whole process of warfare itself—is said to change over time and across cultures” – Antulio Echevarria, U.S. Army War College

8 September 2022 (Crete, Greece) – I’ve just returned from an 8-day sail, armed only with my paper notebooks and colored pens, plus a few very-long-hardcopy reads. No laptop. No mobile phone. Just my emergency marine phone. It’s the opportunity to go over and over the same material, adjusting, correcting, copying out, underlining, coloring. It is a tactile, maybe even childish and seemingly pointless activity, but it always seems to force you to examine things in every detail, from every available point of view.

I’m a passenger these days, no longer skipper due to my back injury, so I hobble about the deck – using the silence and space of the sea for thoughts to unfurl in whatever direction, undisturbed by the instantaneous world back on-shore. Focused instead on “Big Picture” things to which I have not given enough thought.

It was rather pleasant to be absent from the social media firehose, from corrupt political classes, sclerotic bureaucracies, heartless economies, and God-only-knows what multiple, simultaneous crises with epic proportions you all went through while I was gone. Ah, the Age of Permacrisis. Liberal democracies – can you ever govern your way through them ??!!

So in a perverse way it was rather easy to reconnect yesterday and scan through my information firehouse and see authoritarianism, democracy, digital repression, disruptive technologies, dissent, human rights, surveillance, surveillance capitalism, techno-authoritarianism, the Ukraine War and … a new British Prime Minister?

I’ve written about 12,000 words of my long-form essay “Ruminations aboard the Shipwreck Civilization” – my “Really Big Picture” piece, which I have been wrestling with over the past 6 years. I even brought with me for my sail an enormous folder labeled “SHIPWRECK” into which I’ve shoved handwritten and typewritten notes, made in various states of intense reflection, disquietude, and hope. When I took the folder out during the trip, spread out across my bunk, alas its contents did not miraculously assemble themselves into the outline of an e-book – as the mountain of peas, beans, and grains sorted themselves out for Psyche in the Greek myth. But they did remind me how persistently certain realities and urgencies had been haunting me over a period of time. And while Psyche’s task was to separate legume from groat, millet grain from lentil , my task is different – it is rather a work of connection. But the words did flow.

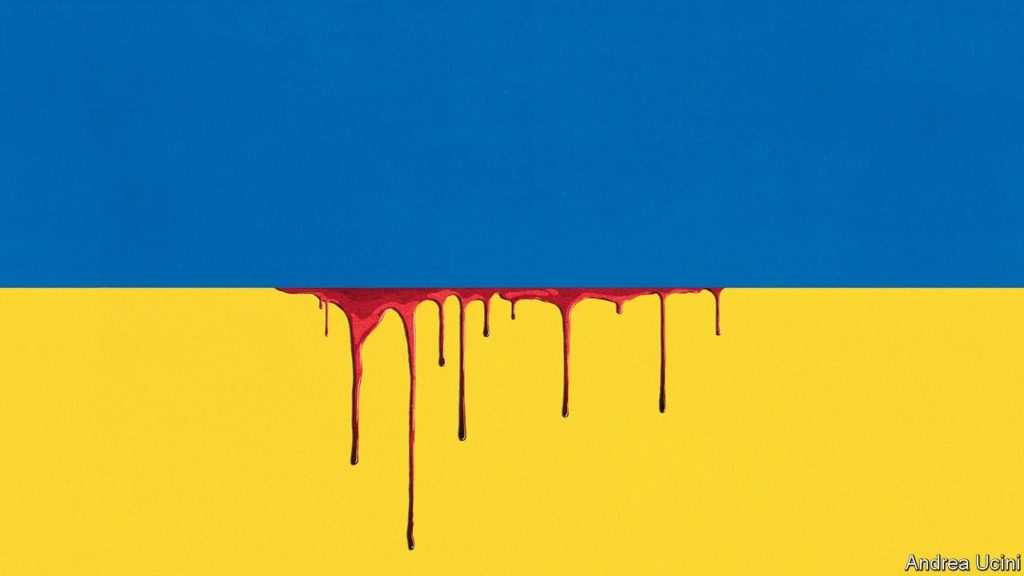

And I did finish a shorter piece on the Ukraine War though it, too, needs a lot of work. But herein a few thoughts:

When he invaded Ukraine, Putin appeared to believe victory would come quickly. Once he realized he’d miscalculated Russia’s military strength and badly underestimated Ukraine’s ability and willingness to fight, as well as US and European determination to back Kyiv, Putin had to scramble. It hasn’t been easy to maintain the fiction that the fighting would never demand compromise from Russia’s government or sacrifice from Russia’s people.

Half a year later, the war has become a costly stalemate. It has killed more Russians (U.S. intelligence and Ukraine estimate hover at 50,000+) than the Soviet troops killed in a decade of war in Afghanistan, and according to U.S. military estimates, Russia has neither enough troops nor enough weapons to subdue Ukraine. I’ll come back to that in more detail in the longer piece.

In addition, Western sanctions have disrupted Russian supply lines and the Russian arms industry. Newly declassified US intelligence documents claim that Russia is now forced to buy millions of artillery shells and rockets from North Korea, low-tech weapons that Russia can’t quickly manufacture in needed quantities. US intelligence has also reported that some drones Russia bought from Iran have proven defective.

To weaken Western support for Ukraine, Putin has weaponized Russian energy exports to Europe and threatened the free flow of grain from Ukraine amid an international food crisis. Neither move has yet had any impact on US and European policy. And while China remains happy to buy discounted Russian oil Europe no longer wants, it has so far proven unwilling to defy US warnings not to violate weapons and parts sanctions against Moscow.

Ukraine, meanwhile, appears to believe it can win the war and has begun a counter-offensive. Its forces are making “verifiable progress” and have “launched likely opportunistic counterattacks” in the country’s south and “retaken several settlements” from Russian forces, according to the Institute for the Study of War, a Washington-based think tank that monitors military action in Ukraine (my best source for independent analysis on the war). Ukrainian partisans have reportedly carried out successful attacks on Russian forces inside Russian-held territory, including Crimea, which has been in Russian hands since 2014.

The big question for Putin: how long can he continue telling the Russian people that Russia is not at war? (Using the word “war” inside Russia to describe military action in Ukraine can still send an offender to prison for 15 years.) More to the point, how long can Putin ignore criticism from hawkish Russian nationalists and their calls to put the country on a war footing that includes a large-scale draft to provide more troops and an admission that tough economic times lie ahead?

The outside world has no evidence that large-scale conscription and other calls for sacrifice would produce public protests that threaten Putin’s future. But his refusal (so far) to take these steps, despite clear evidence that his plans for Ukraine have gone badly off track, suggests he fears the risk of unrest.

In fact, a new study suggests that fear may be well-founded. I had with me during my sail a draft copy of a report that was issued this week in final form, from the Carnegie Center for International Peace. It found that opinions on the war inside Russia “are becoming polarized” in ways that suggest “growing conflict within Russian society”. I tend to take these studies of Russian society with a grain of salt but it does comport with other studies I have seen.

So, in short, Western leaders and Western military intelligence is trying to figure out just how badly must this war go for Putin to tell Russians that their country is truly at war?

The on-the-ground reality is that Ukraine’s fate won’t be decided in Donbas, where the biggest part of Ukrainian and Russian forces are concentrated, but hundreds of miles away, on the more obscure battlefield of the south-west. The country’s future turns on Russia’s ability to hold on to a piece of land on the western side of the Dnieper, between two port cities: Russian-occupied Kherson, and Mykolaiv, less than forty miles north-west. If Ukraine manages to sweep the Russians from Kherson, the western half of the country will be protected by the great barrier of the Dnieper, Putin will suffer a politically damaging defeat and Kyiv will be closer to freeing its biggest ports from Russian blockade.

And that is the biggie: U.S. and European military intel are sceptical of Ukraine’s ability to resist the invaders but are supplying them weapons as if they can. Because winter is coming. If Russia clings on to its western bridgehead, it will retain the potential to swallow more of Ukraine, threatening Mykolaiv, Odesa and the rest of the Ukrainian Black Sea coast all the way to the Danube, and, eventually, the whole country.

When this war broke out, I attended the virtual classes held by the U.S. Army War College. One instructor noted that military hardware and fighting techniques and technology, the likes of which nobody could imagined, would change the character of this war in both predictable and unpredictable ways. But you still had to be mindful of war’s “intangibles”, those elements of conflict that exist in parallel to its changing character, but which have a timeless quality about them. One such concept is the “warlike element” and its relationship to a people’s war or to the arming of an entire nation. It sheds a very useful light on our observations of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

More to come.