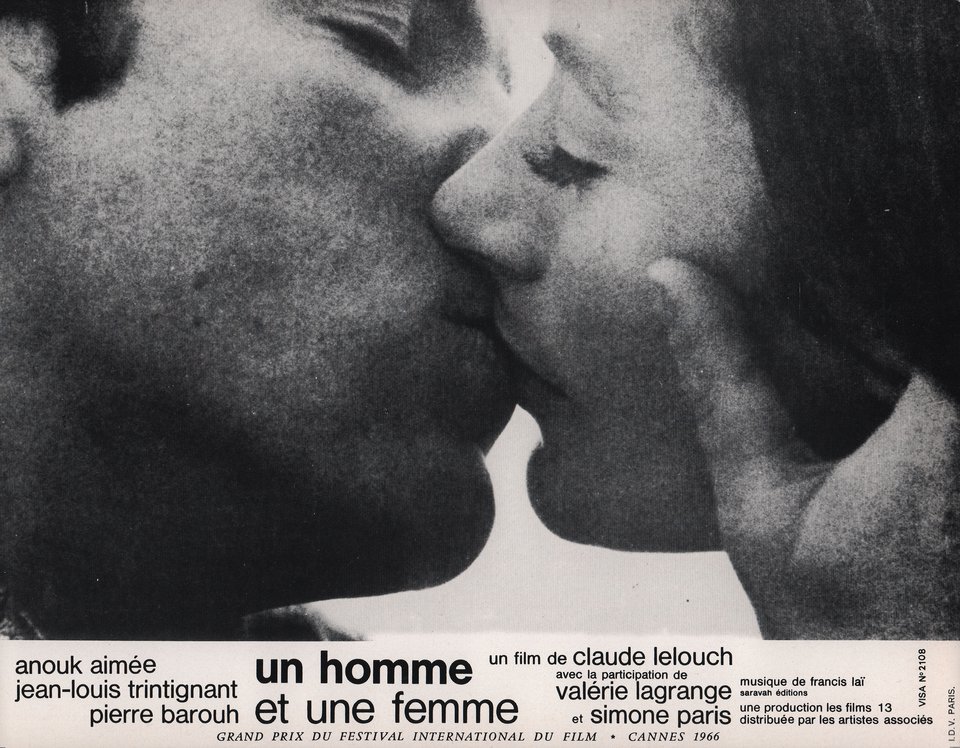

Jean-Louis Trintignant passed away this week at the age of 91. In 1965, the actor shot “A Man and a Woman” under the direction of Claude Lelouch. It is one of my favorite movies, if not just for the magnificent theme song. Lelouch, a distinctive director, was then virtually unknown, but the actor fell under his spell. A film phenomenon was born, placing Trintignant in the history of cinema.

Last night the “Le Monde” film critic Samuel Blumenfeld wrote a magnificent review of Trintignant and of the movie. The following is the English translation. Vous pouvez lire la version originale française en cliquant ici.

11 August 2022 (Mykonos, Greece) – More than the film itself, the banner on the poster for the 1965 film A Decadent Influence by an unknown filmmaker, Claude Lelouch, attracted Nadine Trintignant’s attention. It was two words, in the form of a warning: “Single screening.” The film was released for only one day and in a single cinema in Paris, the Studio Cujas, in the Latin Quarter. The filmmaker was not well, to say the least, and his strange behavior was nothing new. He destroyed his first feature film, Le Propre de l’homme (1960). The second, La Vie de château (1961), remained unfinished.

It was his fourth one that Nadine perceived as a message in a bottle that she felt was her duty to read. She entered the cinema and emerged skeptical. She didn’t like A Decadent Influence. “But,” she said, “I thought Jean-Louis would love this guy’s freedom.” The Jean-Louis she was speaking of was Trintignant, and the guy was Lelouch. She immediately went to pick up her husband at the Gare de Lyon and took him to see the film. The actor fell in love with it, to the point of wanting to meet its creator as soon as possible. After all, Lelouch had himself been in the actor’s position four years earlier, just before shooting The Easy Life: a little bit nowhere.

This 28-year-old director, his junior by seven years, threw Trintignant off right away. The actor was struck by Lelouch’s unusual body. “An amazing body, not pretty, but amazing. Powerful, stocky, a little freaky.” It was simple, he had the impression that this mutant director was born with a camera in his hand and that his body was formed around it.

Trintignant also felt that Lelouch was navigating between financial failures, artistic catastrophes and the wounds of narcissism. If his next film didn’t work, he would have to move on to something else, and the doors of the cinema would be definitively closed. He would go into business, as he imagined it, that is to say, “buying things that he would then sell.” So, if Lelouch had only one more film to make, he might as well be part of the adventure, decided Trintignant.

Lelouch also shared this dream. “I loved him in And God Created Woman,” said the filmmaker. “Every time I saw him again, he called out to me. There was his look – his strikingly sensual lips. His smile was a universal passport. And then his voice resonated in such a special way. As soon as Jean-Louis started to speak, we listened. It was like music, there was something irrational about it. With a voice like that, you can’t say stupid things, it deserves first-rate lyrics.”

‘A love story like real life’

A few months later, he went to see Trintignant and gave him a script with a simple, strong, almost working title: A Man and a Woman. Trintignant would be the man. This last chance script started from an image, or rather an impressionist tableau, which appeared to Lelouch several months earlier, at the end of a car journey between Paris and Deauville (northern France). It was a journey made on a whim, in order to escape his own impasse, and which ended in front of a deserted beach where a young woman, her child and a dog were wandering. The child was very small, he could barely walk, and the dog was running around. The light was overwhelming – the woman’s silhouette was magnificent. But what did her face reveal? What story did it tell? At that moment, no one, not even the artist, could have imagined that this tableau would become the central scene in A Man and a Woman and would travel around the world.

A scenario had to be found for this image. Lelouch imagined a simple love story, the story of a second chance: A film script in which a girl whose husband, a stuntman, died in an accident on a film set, and a lawyer whose wife committed suicide. “I wanted to tell a love story like one that exists in real life,” said Lelouch, “and not one like in the cinema. The story of a man and a woman, both widowed, with their scars.”

Trintignant did not see himself as a doctor or a lawyer. He preferred a profession that made women dream. According to him, there are three such jobs: bullfighter, gynecologist and racing driver. In 1966, on the occasion of the release of A Man and a Woman, he told Philippe Labro from Elle that a “Gynecologist is one of the most seductive professions. The ladies talk about themselves to a man who listens to them, and they talk about intimate things.” But a racing car driver turned out to be more in line with the actor’s tastes and biography.

He himself was the nephew of Maurice Trintignant (1917-2005), winner of the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1954, and the first Frenchman to win a Formula 1 Grand Prix, in Monaco, in 1955. Maurice always remained a totem for Jean-Louis. There were his many records and the aura of the champion, of course. But the mutual admiration between the two men was first and foremost a matter of the personal relationship. Maurice always sustained this young man’s interest in motor racing, in the manner of a returned passion, of a destiny on which he had turned his back.

It is true that the actor only got his driver’s license at the age of 20 and that his parents kept telling him that he did not understand anything about driving and mechanics. But fate got involved, with its share of superstitions and fatalism. His uncle Louis Trintignant was killed in a race at the wheel of his Bugatti in 1933. Maurice had his first race in 1938 in the same car, which he had refurbished himself. As an adult, the actor remained in the shadow of the star, between supporter and mechanic. He sometimes helped Maurice to change the spark plugs, to polish his car, to push it. He made himself a discreet part of the entourage of his champion, a status that he did not have the strength, or the talent, to endorse.

Broken shooting

With A Man and a Woman, Lelouch allowed Trintignant to become the driver of his own dreams. One of the film’s strengths was being, in part, almost a documentary about its main actor, given that the character resembled the actor so much. Moreover, the role and its interpretation allowed many viewers to identify with this man who revealed secret and unfulfilled passions. The racing driver played by Trintignant was not the greatest. If he sometimes finished in the lead, he didn’t often win. He did his job conscientiously. The woman he met loved him because he knew how to find the words to describe his passion. “I think it’s a form of seduction to talk about your job,” Trintignant told Labro.

Lelouch wanted Anouk Aimée to play the female character. But how to reach and convince the actress and icon of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita? Trintignant, who was already a star in Italy, took care of it – they were filming neighbors in Rome – and managed to dispel her doubts about this still emerging director.

A Man and a Woman was made on a shoestring budget. The 470,000 franc budget (the equivalent of about 650,000 euros today) was ridiculously low and the filming had to be limited to three weeks, which was ridiculously short when the average was eight. The team was also reduced to five people: its director, an operator, a stage manager, an assistant who was also a scriptwriter, and a prop maker who also served as a stagehand and electrician. Since Lelouch could not afford to buy enough color film, part of the film was shot in black and white, accidentally giving it a special patina.

The shooting was so poor that Lelouch wondered if he would make it through the first week. Trintignant, on the other hand, was delighted with this contraband atmosphere. The group became a tribe and the proximity welded them together. The actor found what he had been looking for since his arrival in Paris in the early 1950s: a family. The search for a clan was one of the great stories of his life. It was linked to his adolescence, in Provence (southeastern France), which he described in these terms: “My parents were very nice, but I was not very happy at that time, not well in my skin, rather sad … I even had a taste for suicide. Don’t ask me why, I don’t know. My parents got along very well.”

Nadine described a family of provincial bourgeois that were “not funny at all.” The actor’s mother was “wonderful,” according to his future wife. “His father, on the other hand, I would prefer not to talk about,” she said. So let’s talk about the mother. Claire Trintignant regretted that her youngest son was not homosexual, in order to keep him in her bosom – Jean-Louis remained dressed as a girl until the age of 7 – and considered any woman an intruder. She finally came to her senses, but she won on one point: that he would do theater and not motor racing.

Host family

Released from military service in 1958, literally broken, morally disillusioned, no longer going out much, and realizing that his father and mother were not the solution, Trintignant had to invent other families. He first took refuge in Rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière, in Paris, with Claude Langmann’s parents. Langmann was also plagued by doubt and depression, they had at least this in common. It was Trintignant, in part, who introduced his friend to the world of cinema before he became a director and a great producer, under the name of Claude Berri. Trintignant was also seduced by Claude’s father, Hirsch Langmann. He was struck by his personality, his enthusiasm, his way of believing in others and his optimism taking the place of a plan even though he had experienced the Shoah. Trintignant found a piece of lost paradise within this host family.

The actor joined another clan after his marriage in 1960 to Nadine Marquand. His wife’s parents, Jean and Lucienne, were patriarchs with strong personalities, reigning over six children, all linked to the artistic world: Huguette, Carole and Nadine were film editors; Liliane, a collaborator with Coco Chanel, designed costumes; and Serge was an actor, appearing in several films made in the early 1960s by a family friend, Roger Vadim: Les Liaisons dangereuses (1959), Blood and Roses (1960), Please, Not Now! (1961).

That just left Christian Marquand who, by his physique, his haughty face, his immense size, his natural charisma and his taste for a party, was the star of the clan. He appeared in Senso (1954), by Luchino Visconti, and in And God Created Woman (1956), by Vadim, with whom he was very close. His other best friend was Marlon Brando, whom he met in the early 1950s when the American actor was not yet a movie star, but rather a Broadway theater star, and he made Paris his favorite vacation spot.

“In my family, Jean-Louis found a freedom he had not known before,” said Nadine. “At the very beginning of our relationship, I said to myself: ‘He is so shy that this enthusiastic family will scare him.’ But the exact opposite happened, he fell in love with my family. Coming out of a first lunch with my clan, he said, ‘They are all wonderful! I love your dad, I love your mom, your brothers are wonderful.'”

‘He didn’t know his place as an actor’

It was perhaps on the set of A Man and a Woman that Trintignant was happiest. Every morning, Lelouch described the situation to the actors, gave them the essential lines of dialog and threw them into the arena. For the scenes between Aimée and Trintignant, he took the actress aside to explain what she should say to her partner, and then he did the same with the actor. The two actors did not know what the other was going to say. This was Lelouch’s “reportage” method: He created an event and organized himself to capture it as well as possible. This strategy yielded impressive results.

One should also observe Trintignant in the last 20 minutes of the film, at the wheel of his car, on a journey of more than 1,000 kilometers between Monaco and Deauville, in a symbolic race against the clock, after receiving a telegram from Aimée, in which were three words written in the form of a promise: “I love you.” During this journey, Trintignant’s stream of consciousness unfolds, his character’s but also his own, since Lelouch let him improvise his lines: “A woman who writes ‘I love you,'” the actor wonders, “should we go to her house? After all, I’m no female psychologist.” In this wild self-portrait emerged an individual who had everything to learn from life, the very opposite of a star, unless a star is precisely this individual whose clumsiness is upsetting.

Lelouch was convinced that the car played its part in Trintignant’s happiness during filming. “The motorcar racer unlocked many things in him,” said the director. “Jean-Louis often sees the dark side, he is not a positive person. I’m different, I am attracted by the light. We both found ourselves in the car. It is my place of choice. I become the most creative when I’m behind the wheel.”

From the mid-1970s onwards, motor racing was a major part of Trintignant’s life. In 1977, he participated in 14 races in the French production car championship. In 1980, he almost lost his life during the 24 Hours of Le Mans after a flat tire on his Porsche at 300 kilometers per hour. He had his first Monte Carlo rally during the filming of A Man and a Woman and returned four times, between 1977 and 1984. “Jean-Louis’s passion for automobiles has always appeared simple to me,” said Nadine. “He does not know his place as an actor and deplores it. In motor racing, there is a first, a second and a third. At least he knows exactly where he stands, and that suits him.”

Global triumph

Trintignant would never be on a par with Paul Newman, who came second in the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1979, or Steve McQueen, who came second in the 12 Hours of Sebring, in the United States, with one foot in plaster, for one simple reason. “Jean-Louis tends to drive with the blinker on. In the language of the drivers, he does not go fast enough,” said Gérard Pirès, who directed the actor inAct of Aggression (1975). They were both members of the Star Racing Team, made up of stars of the show – Guy Marchand, Claude Brasseur and the stuntman Rémy Julienne – who drove in rallies.

For Trintignant, racing was less of a desire for competition than an inner process. Being behind the wheel gave structure to his solitude and legitimized it. There was also the sensual pleasure of driving, one of the dimensions of the character he plays in A Man and a Woman: Driving fast on a long journey allows him to find Aimée and to figure out what he is going to say to her. “From the tips of your fingers, from the tips of your toes, you can feel the car reacting,” said the actor in Un homme à sa fenêtre (“A Man at his Window”), his 1977 autobiography, “and it pierces your whole body until it nestles in your spine! I don’t know anything else that creates such an emptiness in itself!”

A Man and a Woman was chosen by the Cannes Film Festival selection committee to represent France in 1966. The press screening was interrupted by a machine breakdown. “I thought I was going to die,” said Trintignant. He was surprised by his fragility on the screen, but he was very much in love with the film. He was not the only one. A Man and a Woman won the Palme d’Or tying with The Birds, The Bees and The Italians, by Pietro Germi. With more than four million tickets sold, it became the greatest success of Lelouch’s career and of Trintignant’s as well, if we exclude Les Liaisons dangereuses (1959), by Roger Vadim, and Is Paris Burning? (1966), by René Clément, where he played supporting roles.

A Man and a Woman, which won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film and Best Original Screenplay in 1967, was a global triumph. Better still, this love story became a social phenomenon. Its freedom, its sentimental freshness, the happiness that transpires from a happy ending, the obvious and communicative pleasure of Lelouch filming, Aimée’s fragile beauty and Trintignant’s burning coldness, all crowned by the unstoppable melody written by Francis Lai (Chabadabada…) make it the signature work of an era.

Tame the passing of time

And then, this low-budget film brought in a fortune. From then on, the French actor was neither too small nor too big to shoot. He could choose. This new freedom offered him unprecedented material comfort. “All of a sudden, after A Man and a Woman, we had money. And, like all people who are not used to it, we did a lot of foolish things. We bought houses, I sometimes dressed at the great designers and Jean-Louis changed cars all the time,” said Nadine.

The couple’s life was transformed into a game of Monopoly. A house in Belle-Ile (northwestern France) was sold to buy a new one in Pont-l’Evêque, which was abandoned to settle in Saint-Maximin (southeastern France). It was in Lambesc (southern France) that the actor settled for several years, before settling permanently in Uzès, 40 kilometers from Avignon. A house was not an investment for the actor, nor the ostentatious display of his success. He described the one in Lambesc as “honest and austere,” with many rooms to accommodate the people he loved, but modest enough to allow him to preserve his solitude. “I dream of a house where the walls would be white,” he wrote, “where there would be wooden stools, very hard beds, a certain austerity that is a bit monastic.”

This taste for discretion was his uncle Maurice’s legacy, a man who retired to his vineyard near Nîmes, in search of simplicity after his career as a racing driver. In 1966, Jean-Louis Trintignant bought the vineyards of Rouge Garance, near Uzès, which he cultivated organically. He retained his uncle’s approach: Motor racing also served to tame the passing of time. In the Trintignant universe, seconds are not meant to be erased, but lived, one after the other, with intensity but also in the greatest simplicity. The actor would be well served. The years that followed A Man and a Woman were phenomenal, at least on the level of cinema.