“The elites prefer that everyone sinks rather than arrive at a society in which they have lost power”

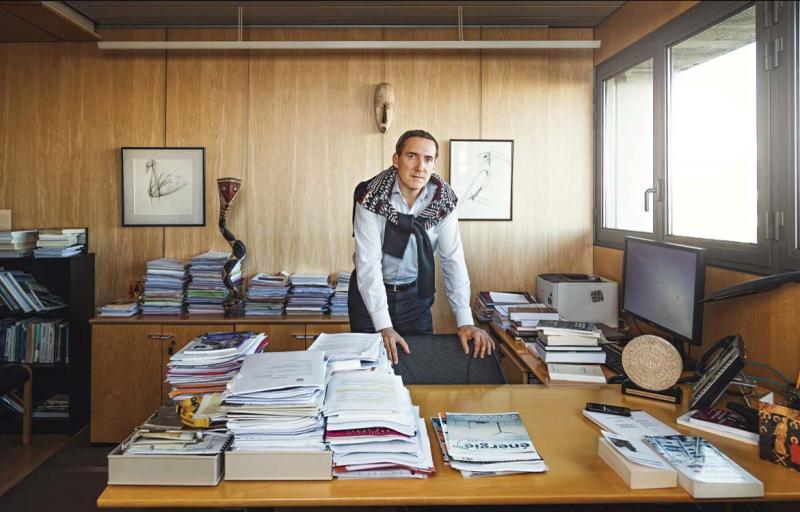

Gaël Giraud

22 July 2022 – Gaël Giraud is chief economist at the Agence française de développement (AFD) and research director at the CNRS. His work focuses on money, financial market regulation, the role of energy in growth and game theory. His seminal works are “Illusion financière” (Financial Illusion) published in 2014, and a volume he co-edited with Cécile Renouard entitled “Vingt propositions pour réformer le capitalisme” (Twenty proposals for reforming capitalism) published in 2012.

The following are a few snippets from a long interview he did with “Socialter”, a French bimonthly magazine that deals mainly with ecological, democratic and social economy issues and now boast a circulation of 45,000 copies. I’ve taken the liberty of translating it to English and providing editor notes.

Gaël Giraud: “part of the elite is suffering from the Titanic syndrome

Can you remind us of the imminent dangers of biodiversity disruption?

No one knows because it will depend on the reaction of humanity. The work we have done at the French Development Agency (AFD) and as part of the Energy and Prosperity Chair suggests that the business-as-usual scenario – where we do not implement a carbon tax with a level and base adjusted to the scale of the challenge, where we do not make any additional efforts – is leading us towards disasters of global proportions.

But it is important to point out right away that such disasters have happened before. A relatively unknown example – which we are now discovering thanks to the work of American historian Mike Davis – is that in 1890 there was a massive El Niño effect [editor’s note: an exceptional climatic phenomenon], which affected Brazil, Africa, India and China, and whose consequences (floods, droughts, etc.) were completely neglected by the colonial administrations of the time. The result: nearly 50 million deaths in a few years. This largely explains the reason for the “backwardness” of the countries of the South compared to European countries. What is phenomenal is that Western administrations were both able to let this happen and to erase it from our memory.

Our greatest task is not to repeat this kind of morbid feat. And it has already begun. Yemen is being destroyed; columns of migrants are fleeing Honduras and Guatemala; the Horn of Africa is tipping over into violence, partly as a result of global warming… Moreover, the collapses underway do not only concern humans. With our animals, we represent 97% of the biomass of vertebrates on Earth: the rest has already been decimated. Regional collapses can only be avoided if there is massive investment in public finances, real decarbonisation (in France, emissions rose by 3.2% last year) and a radical reduction in the material footprint of our consumption, especially that of the wealthiest.

The collapse “predicted” by the Meadows report seems hard to avoid, since nothing is happening anyway…

The first Meadows report [editor’s note: published in 1972, is was the first comprehensive report that discussed the possibility of exponential economic and population growth with finite supply of resources and the adverse effects, better known now as the famous “Limits to Growth”] did not take climate change into account: we did not have the same amount of information then as we do today. It included pollution, the saturation of our waste absorption sinks and the depletion of natural resources. It considered 10 scenarios for the planet. Two led to a global collapse: one in the 2020s, the other in the 2050s and 2060s. Then the Australian physicist Graham Turner did what is called backtesting on the Meadows trajectories and showed that these two scenarios are the ones that most closely match the trajectories currently followed by the planet.

The scarcity of natural resources is already a reality. Copper, for example, is a fundamental metal for its industrial uses – for which we currently have very few substitutes – and for which infrastructures linked to renewable energies are even more demanding than those for fossil fuels. In the years to come, we will therefore need even more copper than we do today. This does not mean that there will be no more copper after 2060, but that we will not be able to increase the annual quantity available, or only at an exorbitant cost in terms of water and energy. This kind of perspective tends to confirm the dark side of the Meadows report if, in the meantime, we do not make efforts in R&D to reduce our dependence on copper and all critical minerals.

In fact, on a global scale, the share of fossil fuel emissions remains at around 80% and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are increasing. How can we explain so much inaction and denial?

The first factor is on the industry side. It is very complicated today for a company to make efforts and switch to a green production model if its competitors do not do so, because they will inevitably have a temporary competitive advantage capable of killing the virtuous industry. As long as we continue to regulate relations between companies through competition, there will be a premium for vice, for brown industry. On the banks’ side, we see the same problem in the granting of green loans. As long as we do not introduce a green supporting factor – that is to say, a bonus in terms of capital requirements for banks that grant green loans and a malus for those that grant brown loans – it will be very difficult for a bank to finance only green loans.

The second factor is that some of the elites are suffering from what we might call “Titanic syndrome”. I tell myself that it’s already too late to change the ship’s course and that we’re going to hit the ice, so I’m busy preserving access to the lifeboats for myself and my family without worrying about the rest of the ship. Meanwhile, I continue to fly every week, polluting in a context where the richest 10% of the planet are responsible for 43% of emissions. A real cynicism is lurking among certain financial elites who tell themselves that, even if they send their children to Scandinavia, they will always manage to secure access to drinking water, clean oxygen, energy and minerals.

In a country like Nigeria, expatriates live in villages built ex nihilo by multinationals. Inside: a swimming pool, a cinema, a concert hall; thermal cars are cleaned with drinking water and a shrink is paid to treat the expat’s depressed spouse. On the other side of the four- to five-metre high walls, flanked by watchtowers, police dogs and barbed wire, Nigerians lack water to drink… This “bunkerization” of certain elites is a fantasy of the “Varennes flight” that completely overlooks the fact that the rich ghettos are closely dependent on their hinterland and the working classes who work there, and that the upheavals in biodiversity also affect Sweden.

Or look at South Africa’s economy which is largely based on coal on the one hand and market finance on the other. This is what allowed the English minority, and somewhat Afrikaner, to retain economic power despite the end of apartheid and 1994. Inequality continues to rise in South Africa. What for? Because giving political freedom to the entire population has not solved the problem of the distribution of power linked to the holding of capital. And the capital in South Africa is coal-fired power plants and finance capital. So how will South Africa’s elites consent to the energy transition as they owe their power only to coal and market finance?

These elites will only agree to make this transition the day they are certain that they can do so under conditions that allow them to guarantee to retain power.

In my opinion, one of the geopolitical blockages of the transition is that our elites are not as stupid as some might say. It is not true that they have not understood the seriousness of climate change, the seriousness of the erosion of biodiversity. They are negotiating in such a way that we are gradually arriving at a transition that is favorable to them and therefore socially unequal.

This brings to mind Bruno Latour‘s view that some of the elites have abandoned the idea of a common world …

Not all, of course! I meet many captains of industry who have understood that the energy transition is the business of today and tomorrow. Even fossil fuels can be “cracked” to produce hydrogen without CO emissions2 .

There is also the “taboo” question of the demographic bomb: how are we going to manage this immense growth and try to re-establish a form of equality?

I do not think that this is a taboo question – at least it should not be. The United Nations’ median scenario for demographic change predicts 9 billion inhabitants on the planet in 2050, 11 billion by the end of the century. This will considerably complicate the resolution of the ecological transition equation. The question naturally arises as to whether it would not be better to limit births in areas where fertility rates remain high. Sub-Saharan Africa is the only region in the world that will experience a strong population surge in the coming decades. Today, about 1.2 billion people live in Africa, and there will be at least 1 billion more in the next 30 years.

Sub-Saharan African States are well aware of this difficulty. The fact remains that it is not as easy as one might think to bend a demographic curve. Everyone has the Chinese example in mind. If China has succeeded in reducing its birth rate to 1.7 children per woman, it is not certain that this is mainly due to the one-child policy. Why? Because Thailand has experienced exactly the same change in its birth rate, without any anti-natalist policy. Conversely, India sterilized 8 million people without any impact on its birth rate! It is very likely that what has allowed the collapse of the Chinese birth rate is that in less than forty years, Beijing has managed to lift 700 million people out of extreme poverty.

Conversely, the fact that the demographic transition in sub-Saharan Africa has slowed or even regressed is largely due to the structural adjustment plans put in place in the 1980s. These plans contributed to the destruction of many of the social services that were previously provided by the States. We must continue to promote the education of young girls, as AFD is doing, but bearing in mind that curbing the demographic growth curve fundamentally implies having resolved the problem of poverty.

When we read your work, we understand that energy is the primary factor of growth, whereas it is a non-issue for many economists. Why can’t we integrate energy and natural resources into economic models?

First, there are technical reasons: the analytical construction of what is called “neo-classical economics” is largely incompatible with the consideration of natural resources. This type of economics is manufactured to justify the reduction of the share of wages in GDP in favour of capital. Wages and capital are supposed to be the only ingredients of GDP, increased by a “magic” variable called “technical progress”.

If we deconstruct this, then the essence of conventional analysis collapses: trickle-down theory, the relevance of structural adjustment plans, including the one imposed on Greece since 2010. Many economists feel unable, rightly or wrongly, to break with this paradigm of a static, equilibrium economy without money and natural resources, and rewrite a dynamic, monetary theory, where the ecosystem services we enjoy, the mineral and energy resources we extract play a fundamental role.

So we should create new indicators of wealth?

Yes, GDP is a very bad indicator. It must be supplemented by a measure of the anthropogenic pressure on ecosystems in the form of an ecological debt that weighs as much as monetary debts. We also need to revise our analytical and accounting framework, because if the economy depends very heavily on the biosphere, then it must, for example, verify the first two laws of thermodynamics. But all neo-classical models blithely violate these two laws, which is probably why much of what we economists say about the impacts of climate change and the collapse of biodiversity makes physicists fall off their chairs.

When they hear William Nordhaus [editor’s note: the latest “Nobel Prize” winner in economics] say that +6°C by the end of the century means a 10% loss of global real GDP, they wonder what kind of world these economists live in. Most of our current models have little to do with the real world. An economy is really a gigantic metabolism, a dissipative structure (in Prigogine’s sense) maintained in disequilibrium by the energy and matter it constantly takes from its environment and the waste it exudes. Just like a galaxy, a cyclone, a Carnot machine, or any living organism. As long as we do not adopt this circular and thermodynamic point of view, we will remain incapable of thinking about the economic collapses in progress and the way to escape the next ones.

What do you hope for?

I have hope in humanity’s capacity for conversion. Even if it is obvious that it will take a long time to convince the sphere of market finance not to opt for the bunkerization scenario. It will certainly be complicated, but I hope that the majority of people will become aware soon enough that a ghettoized world will necessarily be very unpleasant, including for those who will live inside the bunker. Everything must be done to accelerate a participatory and equitable ecological transition where everyone is involved, where we collectively learn to adapt to the warming that has already taken place and where a minority of stowaways will not shirk their responsibilities behind walls.