“I remain entranced, handling goods as they are shoved in, listening and nodding. I have been slowly dissolving into this cavity”

– from Nog, a surreal American cult novel by Rudolph Wurlitzer (1968) wherein a man wanders into situations that completely atomize him

This is the second of three end-of-the-year essays about transformational technologies (and one very transformational company) that will take us into the next decade and maybe beyond. Not predictions. Predictions are a fool’s game. These are transformational technologies that have already set the table. For the first essay, “The Language Machines : a deep look at GPT-3, an AI that has no understanding of what it’s saying”, and an introduction to this end-of-the-year series, click here.

Also, please see links at the end of this post for my entire Amazon series

18 December 2021 (Crete, Greece) — In 1937, the famed writer and activist Upton Sinclair published a novel bearing the subtitle “A Story of Ford-America”. He blasted the callousness of a company worth “a billion dollars” that underpaid its workers while forcing them to engage in repetitive and sometimes dangerous assembly-line labor.

Eight decades later, the market capitalization of Amazon has exceeded $1.7 trillion, while the value of the Ford Motor Company hovers around $30 billion. We have entered the age of one-click America – and as the coronavirus makes Americans more dependent on online shopping, Amazon’s sway will only intensify.

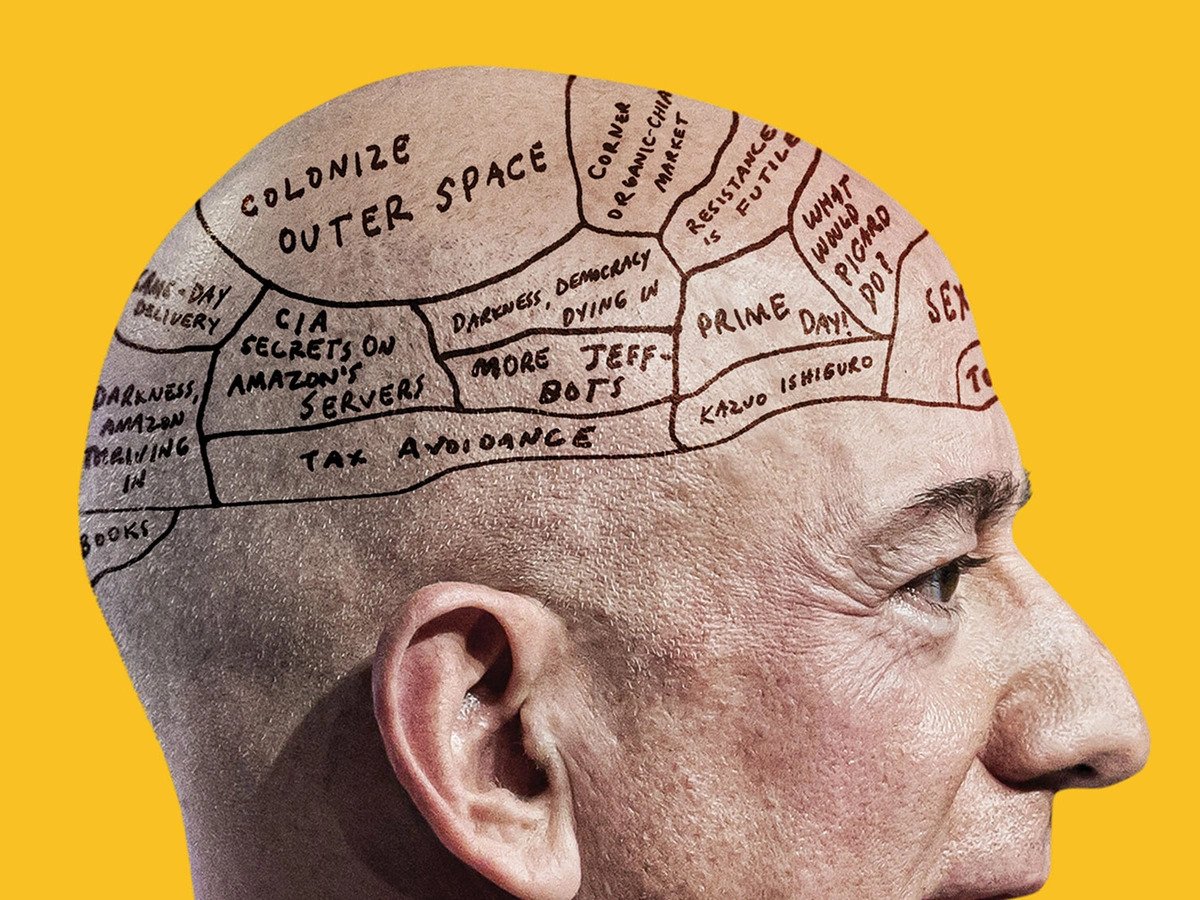

Scores of books and lengthy articles have been written about America’s most conspicuously dominant company – and one that is also beginning to dominate the world. I cannot compete with these scholarly texts as far as breadth but I can offer my view on how America’s recent economic and social history, coupled with its most recent history dealing with the COVID pandemic, has led to an America falling within that company’s growing shadow. Amazon’s sprawling network of delivery hubs, data centers, and corporate campuses, cloud storage, etc. epitomizes a land where winner and loser cities and regions are drifting steadily apart, the civic fabric is unraveling, and work has become increasingly rudimentary and isolated. And Amazon and Jeff Bezos became corporate forces to be reckoned with in Washington, DC – like no other person or company before it. Not John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil, nor J P Morgan and all of his companies. They were amateurs.

In this essay I will focus on only four pieces of the Amazon Goliath:

1. A brief overview of America’s recent economic and political history to explain how and why America has fallen under Amazon’s growing shadow

2. How Amazon set the minimum wage across America – something the Federal government could not do

3. The incredible power of Amazon’s cloud services

4. Amazon’s growing expansion across Europe

1. Understanding Amazon’s immense, growing shadow: a brief U.S. economic and social history

Like all great crisis, the global pandemic of 2020 revealed the weakness of nations it attacked. In the case of the United States that weakness was the extraordinary inequality across different places and communities. When it reached the country, the coronavirus first struck its upper echelons, the highly prosperous precincts that had tighter connections with their global peers than with scruffier places in their own backyard: Seattle, Boston, San Francisco, Manhattan.

But within weeks it had leached into less privileged redoubts, as if guided by an unerring homing instinct for the most vulnerable, among whom it would do the most damage: up in the Bronx, where confirmed cases were twice as likely to be fatal as elsewhere in the city; in central Queens, where it ravaged small houses packed with large families of Bangladeshi and Colombian cab drivers and restaurant workers, and where a hospital demanded that a boy come up with the money for his mother’s cremation while his father lay in intensive care, unlikely to survive; in Detroit, where far more people would die than in Seattle, San Francisco, and Austin combined; and in the small city of Albany, Georgia, where a single funeral seeded a contagion that led to more than sixty deaths within a few weeks in a county of only 90,000 people.

No one should have been surprised by the disparity of the impact, because the divides had been there for anyone to see, getting more noticeable by the year, wherever your travels took you. Maybe you were driving into metropolitan Washington, D.C., from the mountains in West Virginia or western Virginia or western Maryland. One minute you were in small, underpopulated towns blasted by the opioid scourge and bereft of any retail except the omnipresent chain dollar store. Barely an hour later you were heading into the capital’s great exurban maw on a ten-lane interstate, creeping past glass and concrete cubes with inscrutable corporate acronyms, in some of the very wealthiest counties in the country.

Or maybe you were taking the train out of Washington, getting off less than an hour later in Baltimore and experiencing a drop in atmospheric pressure extreme enough to cause dizziness. From a city teeming with money and young strivers to one that was full of emptiness. You emerged from the handsome Beaux Arts train station into a plaza that was too quiet, a major downtown thoroughfare that was too quiet. At a gas station two blocksaway, two people – white woman, Black man – were sitting on the ground, in plain view outside the teller door, snorting something off the back of their fists.

The gaps were everywhere. Between booming Boston and declining in dustrial cities like Lawrence, Fall River, and Springfield. Between New York and the struggling upstate cousins of Syracuse, Rochester, and Buffalo. Between Columbus and the smaller Ohio cities it was pulling away from: Akron, Dayton, and Toledo on down to Chillicothe, Mansfield, and Zanesville. Between Nashville, the belle of the Upper South, and its poor relation, Memphis. Yes, the country had always had richer and poorer places, but the gaps were growing wider than they had ever been. Through the final decades of the nineteenth century and for the first eight decades of the twentieth century, as the country grew into the richest and most powerful nation on earth, poorer parts of the country had been catching up with richer ones.

But starting in 1980, this convergence reversed. In 1980, virtually every area of the country had mean incomes that were within 20 percent of the national average – only metro New York and Washington, D.C., fell above that band, and only parts of the rural South and Southwest fell below it. But by 2013, virtually the entire Northeast Corridor from Boston to Washington and the Northern California coast had incomes more than 20 percent above average. Most startlingly, a huge swath of the country’s interior had incomes more than 20 percent below average – not only the rural South and Southwest but much of the Midwest and Great Plains as well. As for the places already wealthy in 1980, they were now off the charts. Income in the Washington area was a quarter higher than in the rest of the country in 1980. By the middle of 2015, that gap was more than twice as large.

As this regional inequality grew, so did its consequences. There was, above all, the political cost, a rising resentment in the left-behind places that made voters susceptible to racist and nativist appeals from opportunistic candidates and cynical TV networks. Economic decline did not excuse racism and xenophobia – rather, it weaponized it. Such resentment carried especially strong weight in the American political system, which apportions power by land, not just population, most obviously in the Senate. As regions declined and emptied out, those left behind retained outsized clout to express bitterness.

But the damage went beyond that. Regional inequality was making parts of the country incomprehensible to one another – one world wracked with painkillers, the other tainted by elite-college admission schemes. It was making it difficult to settle on nationwide programs that could apply across such wildly disparate contexts – in one set of places, the housing crisis was about blight and abandonment, while in the other, it was all about afford ability and gentrification.

Inequality between regions was also worsening inequality within regions. The more prosperity concentrated in certain cities, the more it concentrated within certain segments of those cities, exacerbating long-standing imbalances or driving those of lesser means out altogether. Dystopian elements in cities such as San Francisco – the homeless defecating on sidewalks in a place with $24 lunch salads and one-bedroom apartments renting for $3,600 on average; high-paid tech workers boarding shuttles to suburban corporate campuses while lower-paid workers settled for 200-square-foot “micro-apartments” or dorm-style arrangements with shared bathrooms or predawn commutes from distant cities such as Stockton – were a feature of both local and national inequality.

The growing imbalance of wealth was making life harder in both sorts of places. It was throwing the whole country off-kilter. To some degree, regional inequality was simply a corollary of income inequality, which itself, by 2018, had grown wider than it had been in the five decades since the census started tracking it – so wide that Moody’s issued a warning that it could threaten the country’s credit profile and “negatively affect economic growth and its sustainability.” As the very rich got ever richer, so did the places where they had always tended to live.

But there were other factors, too. There was the nature of the tech economy, which encouraged agglomeration of talent. There was the changing nature of employment: the less you could expect to spend a career with one company, the more you wanted to be somewhere where there were many employers in your field. With the rise of the two-income couple, you wanted to be somewhere where both of you could find fulfilling work.

There were social dynamics, too. The country’s most successful people were seeking each other out, taking mutual comfort in their comfortable lives, to a degree they never had before. Even within cities, the wealthy had become more likely to live with each other – from 1980 to 2010, the share of upper-income households living in wealthy neighborhoods, rather than more mixed ones, had doubled. Meanwhile, further down the ladder, fraying social bonds and the collapse of the traditional family-trends driven partly by the diminished prosperity in left-behind-places were making it less likely that you were going to move somewhere with greater opportunity. If you were a single mother, you couldn’t leave behind the relative who provided childcare, even if you could hope to afford rent in a thriving city.

It was no accident that wealth was growing more concentrated in certain places at the same time as whole sectors ofthe economy – three-quarters of all U.S. industries, by one estimate – were growing more concentrated in certain companies. This trend had been underway for decades as the federal government had relaxed its opposition to corporate consolidation, and it caused regional imbalance in all sorts of ways. Airline mergers led to less service in smaller cities, which made it harder for them to attract businesses. Consolidation in agriculture meant that less of the money spent on food ended up with those who had actually produced it in rural areas and small towns. Mergers in sectors like banking and insurance meant that many small and midsize cities lost corporate headquarters and the economic and civic benefits that came along with them.

Put most simply, business activity that used to be dispersed across hundreds of companies large and small, whether in media or retail or finance, was increasingly dominated by a handful of giant firms. As a result, profits and growth opportunities once spread across the country were increasingly flowing to the places where those dominant companies were based. With a winner-take-all economy came winner-take-all places.

To the extent that regional inequality and economic concentration were being written about, it was often on their own terms, without relation to one another. In fact, they were intertwined. And as I began to think about this intertwining, it became clear that one of the most natural ways to tell this story was through Amazon, a company that was playing an outsize role in this zero-sum sorting. To take a closer look not so much at the company itself, exactly – that would be the terrain of other accounts such as the 2 volume set by Brad Stone – but rather, to take a closer look at the America that fell in the company’s lengthening shadow.

The company was an ideal frame for understanding the country and what the country was becoming, given how many contemporary forces it represented and helped explain. There was the extreme wealth inequality encapsulated by its founder’s outlandish personal fortune and the modest wages of the vast preponderance of its employees. There was the nature of the work most of them were engaged in: rudimentary and isolating, out on the edge of town, often with unreliable hours and schedules. Bezos and his team had studied the economic and social history of the U.S. over the last 30+ years and specifically located their fulfilment warehouses in the most depressed, economically suffering regions of the U.S. It provided them the cheapest labor and millions of dollars in tax credits and government subsidies. Every community was willing to give Amazon anything it wanted to locate its warehouses in these depressed communities, raising employment levels and creating ripple effects in collateral local industry).

There is also the immense influence the company had amassed over the country’s elected government, both in the states and in Washington, where it had insinuated itself into the power structure of the nation’s capital. There was the unraveling of the civic fabric that the company contributed to, through its undermining of face-to-face commercial activity and the tax base of countless communities (those tax credits and subsidies I noted above). In upending how we consumed – the ways that we fulfilled ourselves – it had recast daily life at its most elemental level.

Amazon was far from the only force driving regional divergence. Rival tech giants, Google and Facebook,had hoovered most of the country’s digital advertising revenue into the Bay Area, in the process eviscerating local journalism; across a swath of other industries, private equity firms based in cities such as New York and Boston had profited greatly by extracting the value of companies scattered in small and midsize cities across the country before shrinking the companies’ payrolls or shutting them down altogether.

But Amazon far more than any other served as the ultimate lens on the country’s divides because it was present just about everywhere, in very different forms. Early on, it had promised to be an equalizing force, offering its initial products -books – to every comer of the country and the world, like a Sears catalog for our time. Over time, in its astonishing proliferation, it had segmented the country into different sorts of places, each with their assigned rank, income, and purpose. It had not only altered the national landscape itself, but also the landscape of opportunity in America – the options that lay before people, what they could aspire to dowith their lives.

And it was the company that was poised more than any of its fellow giants to emerge from the pandemic even more dominant than before. For tens of millions of Americans, the mode of consumption it had pioneered for a quarter century had transformed from a matter of convenience to “one of necessity” – it was now, by official government decree, “essential”. As many of its smaller rivals were furloughing and laying off workers, or preparing to enter bankuptcy or cease operations forever, the company was hiring hundreds of thousands more people to fulfill its new role in American life. As the health risk of these people’s work grew, so did the fraught implications of the easy clicks that directed their exertions. And as the company’s pervasiveness spread, so did those fissures that it had been helping to create all along as the following pieces in this post illuminate.

2. Thanks to its vast size, Amazon now sets the minimum wage and benefits packages in local markets across the U.S.

Amazon’s every move is causing ripple effects well beyond the retail space in local markets throughout America, including on inflation, regional job markets and labor standards. This past year The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times ran separate series on the power and influence of Amazon on the U.S. economy. The following is a mash-up of those series, plus snippets and notes I collected in my research and from the “Amazon is Power” event last winter.

About two years ago, Amazon employees rigged a vehicle to carry a makeshift billboard advertising starting pay of roughly $16 an hour. They drove the truck all over the small Texas city where Jose Ramirez helps run a rival warehouse operation. Within a few months, a handful of the employees at his company, mattress manufacturer Serta Inc., had decamped to Amazon. “We had no choice but to compete,” he said. The company raised its starting pay by roughly $2 to about $15 an hour and has since raised it about another dollar, he said.

As companies across the U.S. fight to find workers, Amazon is emerging as a de facto wage-and-benefit setter for a large pool of low-skilled workers. Business experts have long researched what is known as “the Amazon effect” in disrupting traditional retailers. Now Amazon’s every move is causing ripple effects well beyond the retail space in local markets throughout America, including on inflation, regional job markets and labor standards, according to an examination of federal labor data and interviews with economists, researchers, local employment officials and current and former Amazon employees – those interviews conducted by reporters from the Times and the Journal for the series I noted.

The nation’s second-largest private employer holds mock fulfillment centers in high schools to plant the seeds of future careers, sending recruiters to local fairgrounds and bombarding job boards with promises of large sign-on bonuses and pay – in some cases nearly triple the federal minimum wage. The effect is magnified because Amazon churns through hundreds of thousands of employees each year, creating an even more voracious appetite for labor that often compels the company to push up compensation or improve recruitment in other ways – especially during peak times such as the holiday shopping period now under way.

“Amazon has the economies of scale,” said Jesse McCree, a workforce development official in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, an area of the U.S. where Amazon is competing heavily with other large logistics and warehouse companies. McCree said “They are influencing the market because of scale and name recognition and can afford to pay more than the smaller guys. As they go, even the big companies are going to pay attention”. Similar effects are evident in areas near Austin TX, Los Angeles CA, Cincinnati OH and Louisville, KY.

Typical amongst 100s of stories is this one about produce distributor Castellini near Cincinnati OH. The Chief Executive of the company, Brian Kocher, said “we just cannot get away from Amazon”. The company has wrapped job advertisements around cars, buses and billboards. And recently, when Kocher went to play his favorite Solitaire game on his iPhone, Amazon job ads popped up there, too. Castellini in the past year has raised wages three times, with its pay now starting around $16 an hour. Since many of its employees in the area are Spanish speakers, Castellini has recently focused on hiring and promoting managers who speak the language to better connect with workers. The company also implemented $750 bonuses for any employee who refers family and friends to work there.

Amazon has had a significant impact on the area since 2017, when the company struck a deal with the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport to open a $1.5 billion air hub. Paul Verst, chief executive of Verst Logistics, which provides warehousing, transportation and packaging services for clients such as manufacturers and consumer-goods companies, said construction costs have risen by at least $30 a square foot to a range of about $90 to $100 due to increased demand for building space. Verst recently gave employees a $3-an-hour raise to compete with Amazon. Starting pay now ranges from $16 to $19 an hour. He said his family-owned company aims to retain employees by connecting with them personally. He signs a birthday card for each worker. Tenures for many workers have averaged 10 to 15 years, he said. Still, the company has lost a handful of employees to Amazon, which has advertised pay of $20 or more an hour and $1,000 sign-on bonuses in the area: “It was purely for economic reasons that they left,” he said.

There have been about two job openings for every unemployed person in Cumberland County, the Harrisburg-area county where several Amazon facilities are located. Warehouse competitors include pet food retailer Chewy Inc., United Parcel Service Inc. and food and agriculture giant Cargill Inc. Wage wars in the area have been fierce ever since Amazon raised its starting pay nationally by several dollars to $15 an hour in 2018, local officials said. Much of the battle for hourly employees has played out near a stretch of the area’s Interstate 81 highway, where companies have erected billboard after billboard advertising sign-on bonuses and “immediate openings”. On occasion, Chewy workers have left the company to work at Amazon almost immediately after receiving new training, according to a former area manager. During the Covid-19 pandemic, a period when Amazon hired workers as aggressively as any company in modern history, Cargill was at times so short of employees that it flew workers in from other locations, according to the company. Both Chewy and Cargill now advertise pay near $20 an hour in the area.

Employee turnover in Cumberland County rose after Amazon’s arrival spurred competition among local firms for workers. Three years ago, around the time when Amazon bumped its starting pay to $15 an hour, wages for warehouse employees in Cumberland averaged from $10.50 an hour to $12.50 an hour. Now, they range between $15 to $21 an hour, according to the Cumberland Area Economic Development Corporation. Local and state labor officials all seem to repeat the same mantra: “Amazon is the standard-bearer. Everybody is always following in Amazon’s footsteps and trying to do what Amazon does, but they are always just a little bit behind”.

Job openings across the U.S. outnumber the people who are unemployed, Labor Department figures have shown, demonstrating an unusual tightness in the labor market that has seen a sharp rise in wages. How much of this is due to Amazon’s influence is difficult to pinpoint, due to limited data and the unique influence of the pandemic. But as Amazon’s footprint has grown rapidly across the country, the potential for the company to influence wages or other market dynamics has increased, economists say. Amazon, which had around 1.4 million total employees at the end of September, hires hundreds of thousands of people every year, putting it on pace to surpass Walmart Inc. as the nation’s largest employer in a matter of years.

And a key point is this, emphasised at the “Amazon is Power” webinar I noted above. If they are not leading a wage increase, they are reinforcing it. Everyone is comparing job offers, and they always have Amazon as a benchmark. Even Amazon’s own internal employee challenges ripple through the market. The company’s turnover rate has exceeded more than 100% across many of its facilities, according to an analysis by the Journal.

And, of course, the negative sides. Amazon has recorded higher injury rates than the national average, and its speedy delivery requirements can quickly burn workers out. The company has faced lawsuits, union challenges and government intervention related to the treatment of its workforce, which has pushed it to introduce new safety measures such as body mechanics training for employees and vows from its top leaders to better listen to workers. Amazon press releases continue with the “we are working to better understand the needs of its employees” in order to oppose unions because it prefers to negotiate with workers directly. The company also has said that many of the people it adds are re-hires, demonstrating that many workers return to the company after having earlier left.

Amazon’s wage increases pass through to workers outside the company, researchers have found, as many employers raise their own pay to combat churn. In September, Amazon announced that its starting wage now averages $18.32 an hour, an amount that’s nearly triple the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour. To fight off Amazon, competitors have tried to offer lighter workloads, more flexible schedules, bonus pay and other perks. But Amazon is rolling out new plans to compete in those areas as well.

Amazon wants to use its size and scale to make its jobs as flexible as possible, said Ofori Agboka, an Amazon senior human-resources executive, who agreed to a Times interview. He said having hundreds of thousands of employees makes it easier to offer workers different work hours, a perk many have requested. Amazon recently broadened a program that allows some employees to switch schedules and pick their own work hours, or cancel a shift at the last minute. The company also offers a child-care network to employees and flexible hours for a few weeks for employees transitioning back to work: “What does flexibility mean for each employee, and how can we meet that?” Agboka said.

Candidates are now essentially being hired on the spot, Agboka said, with many workers able to see their start date less than half an hour after beginning an application online. Amazon is also working to fix common retention issues, he said, such as employees who are dismissed after a minor incident like missing work due to an emergency.

It is too early to know how well some of Amazon’s new initiatives to increase flexibility will be felt in the labor force, but its pay increases are already having an enormous widespread impact. Hundreds of employees in and around Louisville KY joined Amazon during one of its hiring sprees. They left jobs paying $15 an hour for Amazon jobs paying $17.50 an hour – and they also got a $3,000 sign-on bonus.

The American workforce is rapidly changing. In August 2021, 4.3 million workers quit their jobs, part of what many are calling “the Great Resignation”. But as I noted in a recent post it is actually more “the Great Shift” because there is a paradigm shift undergoing in the U.S. labor markets. Too much to add to this post.

The best paper I read during my research for this piece was done by researchers from the University of California, Berkeley and Brandeis University. Looking at the numbers over a 4-year period, they found that a 10% increase in Amazon’s advertised hourly wages in 2018 led to an average increase of about 2.6% among other employers in labor markets where Amazon is located. Amazon’s influence on wage increases had a big effect because a large fraction of similar jobs then were below $15 an hour. In comparison, when Walmart and Target Corp. announced $9 starting pay in 2015, the effect was smaller because there was a larger fraction of employers that were already at or above that pay level. Walmart in September raised its minimum wage to $12 an hour. It recently said that in 2022 it might have no choice but to go to $15 in order to compete with Amazon.

But at the same time, the Berkeley/Brandeis researchers found Amazon’s increase in pay failed to raise overall employment levels and actually led to a small decline. While some employers that raised wages hired additional workers, others cut back on employment or hours. In Amazon’s case, the company’s increase to $15 an hour led to an average decrease in “probability of employment” by 0.8 percentage point. Other research has showed similar results. In response to its overall effect on employment, Amazon has previously pointed to the billions it has invested in infrastructure and the amount of jobs it creates.

But this is more the typical vase. In San Marcos, Texas, Amazon established its first fulfillment center in 2016 and soon approached the nearby Texas State University as the area’s largest employer. Other warehouse operators in the area quickly felt the company’s presence. Amazon advertised on radio stations hundreds of miles away and attracted workers from competitors in short order. Amazon now staffs more than 4,500 workers in three facilities throughout that area, with a fourth site recently opened that will employ at least hundreds more. The company has added more than 2,000 employees during the Covid-19 pandemic, according to local data.

But here again, worker churn has been high at the facilities. Turnover in these Texas facilities swelled to 101% in 2017, the first full year Amazon operated there. The rate plunged to 68% by 2019, according to a Journal analysis. That decrease happened after Amazon reduced the number of employees at the San Marcos warehouse, according to the Greater San Marcos Partnership, a local business group. Since Amazon raised its starting pay in 2018, wages in the San Marcos area are also up substantially. Pay grew by 12.7% in the two years after Amazon’s move to $15, compared with 4.3% in the two years preceding it.

Walmart and others matched and sometimes exceeded Amazon’s pay at their facilities to stay competitive. A large sign recently hung from a Walmart distribution center south of Amazon’s San Marcos facility advertising pay of up to $20 an hour. Several companies said they competed with Amazon using flexible schedules, including usually not requiring employees to work on weekends. One manager said “If we were just to compete with hourly rates with Amazon, we would never get there. The biggest discussion around resources in this area has to be around what an employer has to offer as a whole package”. Still, he is short employees.

The Biden administration failed in an attempt to insert a federal minimum wage increase in the last round of economic stimulus legislation, and the level has now gone unchanged for 12 years. The national reach of companies such as Amazon and Walmart means that $15 is being established as an expected hourly wage regardless of federal law. All in all, “the Amazon effect” is in full vigor.

3. As we saw again this month, when the backbone of the internet breaks, huge segments of the global economy become paralyzed

Amazon Web Services (AWS), Amazon’s stunningly profitable cloud division, powers the online presences of millions of users – and by users, I mean Fortune Global 2000 heavyweights ranging from Netflix to iRobot to the Nasdaq stock exchange. Quite simply, AWS is too big and has too many customers for the good of society.

The most infuriating part is that there’s no clear path out of this state of affairs, only murky, tangled, possibly hazardous ones. After the back-to-back outages this month, pundits were screaming “we must start to find solutions to the problem before we’re all forced to reckon with a much larger disaster down the road!!” Good luck with that. But I get it. AWS has made the internet far more reliable than it used to be. But therein lies the problem: on the rare occasions that it does go down, we have nowhere else to turn. Last week the sheer scale of AWS became a bit more tangible to many of us when an 8-hour partial outage sent shockwaves through the global marketplace. Netflix failed to stream. Roombas failed to Roomb. Luckily, Nasdaq had yet to migrate core trading systems onto the AWS cloud, so the U.S. economy continued on (more or less) but financial exchange experts said “it was a near miss”.

Let’s be very clear here: we were not, and are not, and never will be as good as AWS at running infrastructure. Yes, once upon a time, we all ran our own data centers, and they went down a heck of a lot more often than Amazon’s do today. AWS is sufficiently excellent at the operational side of its business that significant outages are rare enough to be headline news around the world. That’s a good thing. Really. It is.

The caveat, however, is that your risk is now concentrated. When your bank’s data center went down, that used to be a bad day for your bank, but it was survivable because the other banks in town probably weren’t affected. Today, when AWS has a bad day, it’s not just your bank or my bank – it’s all the banks everywhere. But as I wrote last week, of the three major cloud providers (AWS, Microsoft’s Azure and Google Cloud), Amazon’s architecture is the best at regional separation. Of those cloud providers, only AWS is bifurcating and trifurcating and re-configuring server architecture to make these outages less *global*.

And because of that, to date, AWS has never had a global service outage. But even so, because of the way it’s structured, an outage that’s ostensibly confined to a single region (for instance, US-East-1, the region in Northern Virginia that has been the locus of many a service disruption, including last week’s) still has the potential to cause service problems on a global scale due to ripple effects.

When it comes to solutions, simple ways of avoiding this concentrated risk flat-out do not work. For instance, “I’m going to avoid AWS’s outages by choosing Google Cloud instead” seems like a sensible response – Google has outages, too, but they’re not correlated with AWS’s. But every website is built with third-party dependencies, which in turn are powered by their own third-party dependencies. Ripple effects.

Note: The best introductory book I can recommend remains Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet (2013) by Andrew Blum. Yes, the book is now 8 years old but the internet’s complex architecture and physical infrastructure is easier to comprehend reading this. It all may be a little bit more sophisticated today but the basic physical infrastructure that underlies the Internet remains the same and this book will lay the groundwork for you.

Let’s say that Stripe is an AWS customer (which it is); even if you run your e-commerce business on Google Cloud, if you process your payments through Stripe, a sufficiently large AWS outage could very well knock out your business anyway. Or let’s even say that Stripe is not an AWS customer. What critical third-party dependencies does it need to function? The whole dependency chain is a rabbit hole with no observable bottom, and the only way to find all those dependencies is via a massive outage.

“I’m going to distribute my workloads across multiple clouds” is another sensible-sounding answer. And yet the problems with this are myriad. There are scores of articles out there on why “multi-Cloud” is not the way to go; start with Kenneth Hui to get a handle on this. The short version is that you’re almost certainly not avoiding AWS as a single point of failure – you’re introducing multiple single points of failure. That is, if you’re spread across two clouds, you’ve effectively just doubled your provider-caused downtime rather than mitigated against it.

Some folks reach instinctively for regulatory action to solve the problem [SURPRISE!] , but regulation will never work. While government does more good than bad by a large margin, I struggle to identify any meaningful action a government could undertake. You really don’t want it dictating the rules for technical architecture. And which government are we talking about here, exactly? Remember that AWS has regions in more than a dozen countries and is adding more all the time. AWS already has terrific incentive to keep its servers functioning: the financial and reputational damage it takes when those servers falter. These outages don’t occur because AWS (or any other cloud provider) doesn’t care, but rather because this stuff is mind-bendingly hard to keep going at scale.

I’ve even heard about “instituting price controls”. The way the big three cloud providers each price data transfer is remarkably similar: Inbound to a cloud provider the transfer is free, while outbound to the internet (say, to a competing provider) is extraordinarily expensive. Despite a lot of needling (and pleas) for help from its competition, its customers and its customers’ customers, AWS in particular has declined to make outgoing data transfers more affordable. And even of you did rethink pricing structure – well, you’d still have to deal with issues ranging from data residency requirements to multivendor coordination to the complex software architecture required to ensure that a single provider going down doesn’t result in a cascade of flaming failures. Oops.

Perhaps the most vexing aspect of our current state vis-à-vis AWS is that … Amazon hasn’t done anything wrong. (Legal beagles: whether the company as a whole attained its current $1.7 trillion scale fairly is outside the scope of this discussion). The extreme impact of this month’s outages could be thought of as a natural consequence of the quality and popularity of AWS’s product. Computers and complex systems are always going to break. Sadly, it’s in their nature.

Bottom line? You pick a single cloud provider and go all in. Whichever one you select is up to you. Collectively, we’re dealing with a problem that goes beyond any one company – and in fact, any one country. As our digital infrastructure has come to rely on just a small handful of players, we’ve all been slow to wake up to the risk we’ve taken on. The unfortunate reality is that these services have become too ubiquitous and too capable for us to backtrack now. We’re stuck with the cloud we’ve got until someone comes up with a better option – and lord knows what the consequences of that will be.

Bezos knew this power, way ahead of his competitors. He knew that Cloud would be the single most important piece of technology to the modern tech boom. The early history of AWS shows that Bezos knew that as a company grew, AWS won need to provide resources to aid in every aspect of that expansion. The business model would allow for flexible usage, so that customers will never need to spend time thinking about whether or not they need to reexamine their computing usage. As Charles Arthur notes in his most recent book Social Warming:

The key for AWS: let companies buy powerful computers cheaply and whenever they need them to handle traffic, to store video, to power a database. It’s not an understatement to say that AWS is the piece of infrastructure that has enabled the current tech boom. The only single technology which might come close to it is the smartphone.

It makes perfect sense. The 2010s tech industry was built on quickly scaling a product to as many users as possible. It’s based, on other words, on fast growth. AWS and its competitors are what permit that fast growth. They have taken the normally considerable equipment costs – of servers, cables, hard drives, and power supplies – and abstracted them away. Entrepreneurs and coders can think about and purchase computing power on an as-needed basis, while the physical data centers they’re actually using sit far away in Virginia or Oregon – or Dubai or Goa.

Bezos launched AWS in 2006 – the first such cloud service. Bezos said AWS “would come to dominate the market” – as Amazon seems to do in all markets it enters. Bezos was right:

– AWS would provide the guts that lets Netflix stream billions of hours of movies and TV shows, so both the modern habit of unplanned binge-watching and the aversion to network TV shows is made possible by the service.

– When Healthcare.gov was being revamped, there was little discussion. The major parts of the website were moved to AWS.

– Spotify said it was the only cloud provider that could provide the company’s cloud storage needs

– Even the police body camera debate turned on AWS. Taser’s hosted service for body-cam footage and other kinds of digital evidence (such as Evidence.com) are actually shells built on AWS.

– And the CIA made it a done deal, moving 90% of its computing power to a custom built AWS setup – followed by 32 other Federal government agencies.

And on and on and on. AWS is so large and present in the computing world that it’s far outpaced its competitors. As of the first half of 2021, four independent analyst reports clocked AWS as having over a third of the market at 34.4%, with Azure following behind at 20%, and Google Cloud at 9%. AWS has 81 availability zones in which its servers are located – with Azure at 62. Overall, AWS spans 245 countries and territories – swamping its competitors.

AWS is a cash juggernaut for Amazon. AWS revenue increases, on average, 30% each quarter. Analysts have computed AWS will have an annualized revenue run rate of $64.44 billion for 2021, generating 18% of Amazon’s total 2021 revenue.

AWS have shaken up the computing world in the same way that Amazon changed America’s retail space. And it’s only just started.

And an addendum: AWS somewhat a child of 9-11

At 9:37 a.m. on September 11, 2001, American Airlines Flight 77 bound from Dulles International Airport to Los Angeles flew into the western side of the Pentagon. The crash killed 125 people, in addition to the 64 on the plane. This would have been the deadliest terrorist attack on Ameri can soil, with an even greater toll than the Oklahoma City bombing of 1995, but it was overshadowed by the much deadlier and more visually arresting attacks that same morning in New York. Further cloaking the deaths at the Pentagon was the discretion inherent to the military – seven of the victims were from the Defense Intelligence Agency, while others were contractors with varying levels of classified status. Where Ground Zero in New York would be memorialized by a museum and two large reflecting pools, the Pentagon would feature only a minimalist memorial consisting of a series of benches on the building’s western side.

The local legacy of the Pentagon attack was complicated by something else, too. After 9/11, a metropolitan area already made prosperous by the influence industry would belifted to a whole new level of wealth by the national security industry. The government reacted to the humiliation of having failed to detect warning signs of the attacks by allocating billions to detect another one. And much of that spending was absorbed by Washington. Thirty-three federal building complexes designed for top-secret intelligence were built in the area in the decade after the attacks -their square footage is equivalent to almost three Pentagons.

By 2009, the U.S. intelligence budget had grown to $75 billion, two and a half times what it had been at the time of the attacks. Much of that spending went to the government giants based in Washington. The Pentagon’s Defense Intelligence Agency grew from 7,500 employees in 2002 to 16,500 in 2011. The National Security Agency, the eavesdropper on the world based at Fort Meade in the Mary land suburbs, doubled its budget over the same period. The Department of Homeland Security was created from scratch, twenty-two agencies thrown together under their new Orwellian name, with a planned $3.4 billion headquarters at the former St. Elizabeths mental hospital overlooking Washington.

But much of the spending would be dispersed to the archipelago of private sector contractors that saw a business opportunity and leapt toward it. Of the 854,000 people granted top-secret clearances by 2011, 265,000 were contractors, not government employees, according to The Washington Post. The CIA’s head count included roughly 10,000 contract employees from more than a hundred firms – more than a third of the agency’s workforce. At the Department of Homeland Security, there were as many contractors as federal employees. Robert Gates, Obama’s first secretary of defense, admitted to The Post that he didn’t even know how many contractors were employed in his own office. The ranks of contractors had grown even though they cost the agencies who employed them considerably more than regular federal employees did.

Many of the contract employees worked for giants like Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, and Raytheon, which vied for applicants with coveted security clearances by dangling $15,000 signing bonuses and BMWs. General Dynamics, which set up and managed Homeland Security’s offices, saw its revenue more than triple between 2000 and 2009, to almost $32 billion, while its workforce doubled to more than 90,000.

But countless other private employees worked at the smaller, anonymous companies that had proliferated across the region-the homeland security entrepreneurs. They had opaque names like SGIS and Abraxas and Carahsoft. They were often launched in the bedroom or den of their opportunistic founder. They grew as fast as they could to absorb the gusher of taxpayer dollars – by 2010, the government’s spending on contractors had doubled to $80 billion.

And with the contracting pot growing so fast, so did the demand for connections to help land contracts: from 2000 to 2011, money spent on Washington lobbyists more than doubled, to $3.3 billion. Far from supplanting the city’s influence industry, the new homeland security complex was only fueling its growth.

The new industry was changing the face of the local landscape. At Liberty Crossing, a gargantuan complex in McLean, armed guards and hydraulic steel barriers guarded the headquarters of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and National Counterterrorism Center. Buildings made to look like warehouses actually held eavesdrop-proof rooms available for rent. Windowless behemoths suddenly appeared in exurban farmland with no identifying signs – unrecognized by Google Maps. Vans raced down secondary highways and through shopping plaza lots in training runs for tracking counterintelligence targets. Denizens of this new landscape spoke their own language – they compared the size of their SCIFs (sensitive compartmented information facility) or whispered about SAPs (Special Access Program); when asked at happy hours at Applebee’s or Chili’s where they worked, they mumbled, “With the military.”

As Brad Stone lays out in his second book about Amazon, “Amazon Unbound: Jeff Bezos and the Invention of a Global Empire“, the new industry would not only transform the D.C. region physically, but technologically. And the industry would drew a new class to Washington – more interested in technology than government, more driven by profits than power. Amazon begin to hire many of the intelligence community insiders in the Bush (and later Obama) administrations. But it was easiest to recruit top-grade former officials on the Democratic side. The tech industry had leaned liberal since at least the early 1990s, after all, when Democrats such as Bill Clinton and the technophile Al Gorehad recognized where the future lay and helped draw Silicon Valley away from its libertarian, pro-business moorings in the Republican Party.

Bezos had already been building AWS for its corporate clients but he would hit the motherland with a stream of Federal government cloud contracts.

4. Amazon continues ramping up in Europe

Earlier this year I published a long piece on how Amazon was ratcheting up efforts to expand its workforce and logistics network in Europe. Experts say the strategy will strengthen the company’s foothold in the region, where it has already gained significant traction during the pandemic. Over the past decade, Amazon has invested heavily in building its shipping infrastructure and services in Europe, where it now has more than 135 sites including corporate offices, technology development centers, fulfillment centers and Amazon Web Services data centers.

As online shopping accelerated across Europe during the pandemic, the company doubled down on its investments by adding 20,000 new jobs, growing its total workforce to more than 135,000 across 15 European countries. The company plans to hire thousands more European employees in areas such as operations, machine learning and software and cloud development. The lion’s share of revenue still comes from North America, but the company is pursuing international growth as more growth is expected in markets outside of the U.S.

For this piece I’ll just focus on one aspect:

In recent years, Amazon has attracted wide attention with its effort to become a force in the grocery industry, from its $13.7 billion acquisition of Whole Foods to its flashy rollout of tech-enabled stores like Amazon Fresh and Amazon Go. But the internet retailer has also quietly been laying the groundwork to become a major player in a less visible and potentially more lucrative area: the grocery-delivery market, which in the U.S. has largely been the domain of Instacart. Over the last year, Amazon has launched a new business in the U.K.- referred to internally as Amazon Fresh Marketplace—that bears a striking resemblance to Instacart. Prime subscribers can use the Amazon app or website to order groceries from two major U.K. supermarkets, with same-day delivery fulfilled by Amazon Flex drivers.

Amazon plans to greatly expand its the online grocery-ordering and -delivery program throughout Europe and in the U.S. in 2022. That will put it in direct competition with Instacart as well as other companies expanding in app-based grocery deliveries, such as DoorDash and Uber. Clues about Amazon’s plans have surfaced in eight separate job listings the company has posted in recent months for management positions on what it describes as its “fast-growing” grocery partnerships team, which operates out of Los Angeles CA, Seattle WA and Arlington VA.

Full disclosure: I own a job posting service and Amazon is a client. We handle multiple job postings on their behalf for fulfilment, legal technology, media and other positions.

Media pundits have focused on several senior account manager positions that describe the role’s responsibilities as “[building] lasting relationships with future Grocery partners…managing Fresh Grocery merchants” and “representing Amazon when meeting with merchant partners.” It is unclear which U.S. supermarkets Amazon will partner with, but similar job postings in Europe and the U.K. described them as “marquee grocers.”

Amazon has been experimenting with grocery delivery for more than a decade now, but its efforts have largely centered on delivering its own grocery goods. Expanding those efforts to deliver for other supermarkets would reflect the strategy that Amazon has pursued as it has expanded its online marketplace from books to an “everything store.” The internet retailer sells products from its in-house brands alongside products from third-parties and direct competitors, and charges outside sellers fees for the right to list their products on Amazon and use its delivery services.

Amazon’s expansion will intensify what is already shaping up to be a bloody battle for market share in the grocery deliver sector next year. Already app-based restaurant-delivery services like DoorDash and Uber’s Uber Eats are ramping up their grocery-delivery efforts. Earlier this year, DoorDash announced a deal to deliver groceries for the Albertsons supermarket chain, and Uber recently acquired grocery-delivery firm Cornershop.

There’s also the bevy of instant-delivery startups – including Jokr, Fridge No More and Buyk – that have recently sprung up in major metropolitan areas like New York. These players, which aim to deliver groceries in 15 minutes or less, are all trying to cash in on a fast-growing market, one that took off last year thanks to pandemic lockdowns. Online grocery sales in the U.S. grew nearly 64% year over year in 2020, and 80% in the U.K. the same year, according to estimates from research firm eMarketer. That competition was already expected to erode Instacart’s market share, which in 2020 was a whopping 84% of the U.S. grocery intermediary market, delivering goods for established brick-and-mortar grocers such as Wegmans and Costco. Amazon’s entry threatens Instacart’s dominance even more.

Instacart’s revenue growth has already slowed sharply. After tripling during 2020 to around $1.5 billion, revenue is expected to grow only 10% this year. Instacart has pushed off plans for a public offering until 2022 or later as it tries to better distinguish its offerings for grocery retailers to stand out in an increasingly crowded market. The company is also grappling with continuing executive turnover: last week newly hired president Carolyn Everson said she would leave after only three months following a dispute with CEO Fidji Simo over the management of grocer relationships.

Instacart has already made clear it will respond to Amazon’s entry into the market by casting itself as a more reliable ally. Instacart has said it sees Amazon as a major threat to the grocers it partners with, because Amazon’s Whole Foods is a direct competitor. In a recent interview with Bloomberg, Simo noted that its strategy is to partner with grocers rather than compete with them.

Amazon has tried a similar service before. Beginning in 2015, Amazon began testing a program to deliver products from local grocery stores. Customers could use the Amazon Prime Now app to order groceries from select local grocers in Manhattan, Seattle, Los Angeles, Portland, Chicago and San Diego. However, the program fizzled out within a few years, and as of 2020 the external merchant offerings on the Prime Now app ranged from nonexistent to sparse. Earlier this year, Amazon shuttered the Prime Now app, and moved online grocery-ordering services for Whole Foods and Amazon Fresh to the main Amazon website. The only relics left of the service are partnerships Amazon has with Seattle-based drugstore Bartell Drugs and grocer Bristol Farms in southern California, which let locals order goods for delivery by Amazon.

An Amazon spokesperson did confirmed that Amazon is providing grocery-delivery services to third-party retailers in the U.S., U.K. and Europe with an intent to focus on the UK and Continental Europe. But Amazon will not comment on the status of Amazon’s ongoing or future partnerships with large European operations. But if you stop and think about it and just scan the European press you see reference to partnerships in Europe via Amazon Prime members “that provide more choice, value and convenience while our partners benefit from increased visibility for their selection and service”. That will require some very good delivery partners across Europe.

In the U.K. Amazon’s Fresh Marketplace program displays grocery products from supermarket chains Morrisons and Co-op in separate digital storefronts on the Amazon website and app, similar to the way Whole Foods products are displayed on Amazon’s website in the U.S. A former senior-level Amazon employee familiar with the program confirmed that Amazon is working to expand the Fresh Marketplace concept in the U.S. and Europe.

I think the view is, for Amazon, that if they can convince some large retailers in the U.K. and in Europe to get on board with selling groceries through its marketplace, it will bleed over into the United States. One of the big questions is whether Amazon will be able to sign up grocers for its service, given that it competes with them through Whole Foods. Some big-name retailers have long been suspicious of Amazon’s intentions. Walmart, for instance, required that some of its vendors stop using Amazon Web Services in 2017, fearing that its biggest competitor could end up using its data. Amazon’s Whole Foods acquisition and the recent rollout of Amazon Fresh stores – around 10 in the U.K. and 22 in the U.S. – have driven many grocers into the arms of Instacart.

Side note: I did an analysis of the Whole Foods acquisition back in 2017 and my view this was more about artificial intelligence than groceries.

I suspects that one of the reasons Amazon is expanding its third-party marketplace in the U.K. and Europe first is because retailers abroad are less paranoid about what Amazon may be doing with their data, particularly due to the strength of European privacy and data collection laws. Amazon already has a foothold in France following a 2018 partnership with supermarket giant Monoprix under its since-shuttered Prime Now program. And the internet retailer plans to expand to Germany – Amazon’s largest European market – in the first quarter of 2022.

The company faced similar skepticism from American grocery retailers when it first attempted to onboard local grocers to the Prime Now app in 2015. A 2017 report by industry publication Grocery Dive put it plainly: “Will Amazon Prime Now help online grocery grow, or is it a deal with the devil?” The report highlighted concerns among industry analysts that grocers who rely upon Amazon Prime Now may be diluting their relationships with customers while also providing a wealth of customer shopping data to a major competitor. Amazon has experienced similar pushback from American retailers around the adoption of its cashierless Just Walk Out technology. The checkout-free tech uses computer vision and a bevy of overhead cameras to allow customers to walk into a store, sign in with an app, grab the items they want to purchase and leave without formally checking out. Customers are billed for the items they took after departing the store.

Amazon has deployed the technology in Amazon Fresh supermarkets in the U.S. and U.K., and has reportedly licensed the technology to a handful of convenience stores and retailers. Last month, Amazon announced that it had signed a deal with Sainsbury’s, one of the U.K.’s largest supermarket chains, to open a checkout-free convenience store in London. It’s unclear whether supermarkets and large-scale retailers will feel comfortable licensing the technology.

Get ready, Europe. An Amazon Fresh store may just open up next door.

CONCLUDING NOTES

Amazon has transformed the geography of wealth and power. You cannot understand America without understanding the power of this giant company’s shadow. It is estimated that this year Bezos’s net worth will rise more than $75 billion (or 60 percent over last year) to $202 billion. During roughly the same period, according to Amazon, almost 20,000 of Amazon’s frontline workers, such as warehouse employees and Whole Foods clerks, tested positive for the coronavirus. Step back, and the pattern holds. The world’s billionaires increased their wealth by about a fifth over the course of last year – to more than $11 trillion, according to Forbes. Meanwhile, a quarter of U.S. adults said someone in their household was laid off or lost a job because of the pandemic.

And, no. Amazon cannot be blamed for everything. Larger forces such as globalization, gentrification, the opioid crisis and COVID have had a greater impact than any one corporation’s influence.

But in so, so many cases it’s Amazon’s world and we just live in it. Measured by importance to modern life and ability to shape the American economy in its own image, Amazon is second to none. That remarkable influence stems from the sheer variety of its business lines and the way it touches our everyday lives. Born in 1994 as a modest online bookseller, Amazon has grown organically and by accretion into an internet giant that plays in nearly every sector, from producing movies to transporting freight to running our Internet. I’ve merely skimmed the surface in this piece.

And on a larger scale it shows how digital powers will reshape the global order. After rioters stormed the U.S. Capitol on 6 January 2021, some of the United States’ most powerful institutions sprang into action to punish the leaders of the failed insurrection. But they weren’t the ones you might expect. Facebook and Twitter suspended the accounts of President Donald Trump for posts praising the rioters. Amazon, Apple, and Google effectively banished Parler, an alternative to Twitter that Trump’s supporters had used to encourage and coordinate the attack, by blocking its access to Web-hosting services and app stores. Major financial service apps, such as PayPal and Stripe, stopped processing payments for the Trump campaign and for accounts that had funded travel expenses to Washington, D.C., for Trump’s supporters.

The speed of these technology companies’ reactions stands in stark contrast to the feeble response from the United States’ governing institutions. Congress still has not censured Trump for his role in the storming of the Capitol, and his enablers will successfully run out the clock because they know how feeble to American “justice” system really is. Ironically, law enforcement agencies were able to arrest some individual rioters – but only because in 90% of the cases they could only track clues they left on social media about their participation in the fiasco.

States have been the primary actors in global affairs for nearly 400 years. That is starting to change, as a handful of large technology companies rival them for geopolitical influence. The aftermath of the January 6th riot serves as the latest proof that Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Twitter are no longer merely large companies; they have taken control of aspects of society, the economy, and national security that were long the exclusive preserve of the state. The same goes for Chinese technology companies, such as Alibaba, ByteDance, and Tencent. Nonstate actors are increasingly shaping geopolitics, with technology companies in the lead. And although Europe wants to play, its companies do not have the size or geopolitical influence to compete with their American and Chinese counterparts.

In a nutshell: these technology companies differ from their formidable predecessors is that they are increasingly providing a full spectrum of both the digital and the real-world products that are required to run a modern society. Although private companies have long played a role in delivering basic needs, from medicine to energy, today’s rapidly digitizing economy depends on a more complex array of goods, services, and information flows.

This does not mean that societies are heading toward a future that witnesses the demise of the nation-state, the end of governments, and the dissolution of borders. This needs a more nuanced discussion. But the big technology companies are increasingly national and geopolitical actors in and of themselves. Only by updating our understanding of their national and geopolitical power can we make better sense of this brave new digital world.

OTHER POSTS IN MY AMAZON SERIES

Monopolies really know best: just ask Amazon

Amazon is planning to open 260 supermarkets in the UK

Amazon continues to channel The Google

Amazon: a company perilously close to invincible

The European Commission: “Amazon has illegally abused market position with Big Data tactics”

Introducing the new AT&T (Amazon Telephone & Telegraph?) and the thirst for data

Amazon moves closer to the legal artificial intelligence sector