Researchers in South Africa and Europe are racing to determine whether the fast-spreading Omicron COVID variant which first surfaced in Botswana/South Africa (but is now also in Europe) poses a threat to COVID vaccines’ effectiveness.

One of the big fears: a virus undergoing multiple mutations is always problematic. But when a single variant itself has multiple mutations, it’s likely going to contribute to further evasion. That is the growing danger with this latest COVID variant.

Early on they had decided not to use “Nu” due to potential confusion, and now they skipped over “Xi”. Omicron sounds more like a Spider Man villain.

27 November 2021 – Researchers in South Africa and Europe are racing to track the rise of a new variant of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus that causes COVID-19, that variant now called Omicron. The variant harbors a large number of the mutations found in other variants, including Delta, and it seems to be spreading quickly across South Africa.

I have been in Washington D.C. for a film project and I had the opportunity to attend a special briefing at the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, as well as a webinar by the Nature magazine COVID epidemiology unit. Both of those institutions have been invaluable sources for my COVID series (you can access my COVID archive here).

Concern is focused on one factor: the Omicron variant has an eye-watering number of mutations, many of which could help it dodge immunity, or make it more infectious. Since the Delta variant, there have been eight other variants named after letters of the Greek alphabet, but none have triggered this much worry. Based on the first looks, this variant has about 50 mutations, with 30 in the spike protein (I will explain that below) and 10 in the receptor binding motif, which is the protein provides the entry point for the coronavirus to hook into and infect a wide range of human cells. That’s greater than any other mutated strain we’ve seen, more than double what we had in Delta.

If you look at those mutations as mutations that increase infectivity, mutations that evade the immune response, both from vaccines and natural immunity, mutations that cause increased transmissibility, it’s a highly complex mutation. There are new ones we haven’t seen before, so we don’t know how they’re going to interact in common. So all of this makes it a pretty complex, challenging variant and I think we will need to learn a lot more about it before we can say anything definite about it.

But simply put: changes to the spike protein are particularly concerning because vaccines have been designed to help the body recognise the spike shape. If they change too much, the immune system will be blind to an infection. Vaccines would stop working and all our hard won protection would be lost. Antibodies made by the body from a natural infection may also struggle to see off this new interloper. There are also mutations at the furin cleavage site, which is alarming as this is an area that helps the virus get into human cells, and which makes it so infectious.

The Johns Hopkins and Nature briefings I attended were geared toward people versed in epidemiology and up-to-speed on COVID. As my regular readers know, my media team and I (which at the time was composed of 6 full-time staff with an added 6 freelancers) jumped into “everything-coronavirus” in March 2020 and we produced 200+ articles and private client memos. I was venturing onto ground where I had no guarantee of safety or of academic legitimacy (a second, minor university degree in physics, of all things, but an avid reader of all-things-science my entire life) … but I did my homework. It certainly was not my intention to pass myself off as a scholar, nor as someone of dazzling erudition. It was enough for me to act as a messenger for those who did have the knowledge, and offer my own reflections on that knowledge. I credit the teams at the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Center who worked me through the science.

There has been a tsunami of material to read. With a high level of complexity. The unprecedented uncertainty amid the coronavirus pandemic … especially the data … had decimated our carefully laid plans and unsettled our minds at equal pace. This coronavirus, with its health, social, scientific and economic impacts, had made the content production engine of this world go into overdrive, leaving most of us struggling within an infodemic.

But our team prevailed. Yes, I am still struggling with this stuff. I still have much to learn. And so far my biggest take-away is that all these complex/interlocking dynamics have revealed a basic absurdity at the heart of our global society. It is not a system aimed at satisfying our desires and needs, at providing humans with greater amounts of physical utility. It is instead governed by impersonal pressures to turn goods into value, to constantly make, sell, buy, and consume commodities in an endless spiral and ignoring the effect of that system on the “normal human”. But that’s fodder for another post.

So right now, for this post, I shall not blind you with a lot of science (but there will be some) but rather try and give you the …

Although full testing and analysis is still far away, epidemiologists are concerned about the following factors based on the initial research on Omicron:

1. One mutation, P681H, has previously been found in alpha, mu and some gamma cases. But this is the first time that two changes have been seen in a single variant.

2. These changes are likely to enhance the virus’s ability to enter cells, increasing viral load and making it more transmissible.

3. There are also two mutations in an area called the nucleocapsid, R203K and G204R, which were present in the alpha, gamma and lambda variants, and are known to increase infectivity.

4. As if this were not enough, there are also several changes that have never been seen before, which are also alarming scientists.

Omicron was first identified in Botswana earlier this month and has since turned up in a traveller arriving in Hong Kong from South Africa. Scientists are also trying to understand the variant’s properties, such as whether it can evade immune responses triggered by vaccines and whether it causes more or less severe disease than other variants do. And there is still a question of whether this variant did, in fact, originate in South Africa.

But there was the usual knee-jerk reaction. The UK along with other countries have barred foreign nationals from several southern African nations. And for my UK friends, it looks like incompetence will once again reign supreme. As noted in a series of Tweets yesterday, passengers arriving at Heathrow Airport yesterday morning and late yesterday afternoon – the last flights from South Africa – have noted “we were met by UK health officials but no additional precautions, no tests, were given for the hundreds of arriving passengers. And one flight came directly from Gauteng – the province where the new variant was identified”.

There is still very much yet to be considered. Two quotes from the Nature magazine webinar and a companion summary article published last night:

* Penny Moore, a virologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, whose lab is gauging the variant’s potential to dodge immunity from vaccines and previous infections: “We’re flying at warp speed. There are many anecdotal reports of reinfections and of cases in vaccinated individuals, but at this stage it’s too early to tell anything”.

* Richard Lessells, an infectious-diseases physician at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa: “There’s a lot we don’t understand about this variant. The mutation profile gives us concern, but now we need to do the work to understand the significance of this variant and what it means for the response to the pandemic.”

Researchers also need to measure the variant’s potential to spread globally — possibly sparking new waves of infection or exacerbating ongoing rises being driven by Delta.

Note: as of 3am EST 27 November 2021 when this post was written there were 87 confirmed cases and 993 “probable” cases of Omicron:

| LOCATION | CONFIRMED | PROBABLE |

| South Africa | 77 | 990 |

| Botswana | 6 | – |

| Hong Kong | 2 | – |

| Israel | 1 | 3 |

| Belgium | 1 | – |

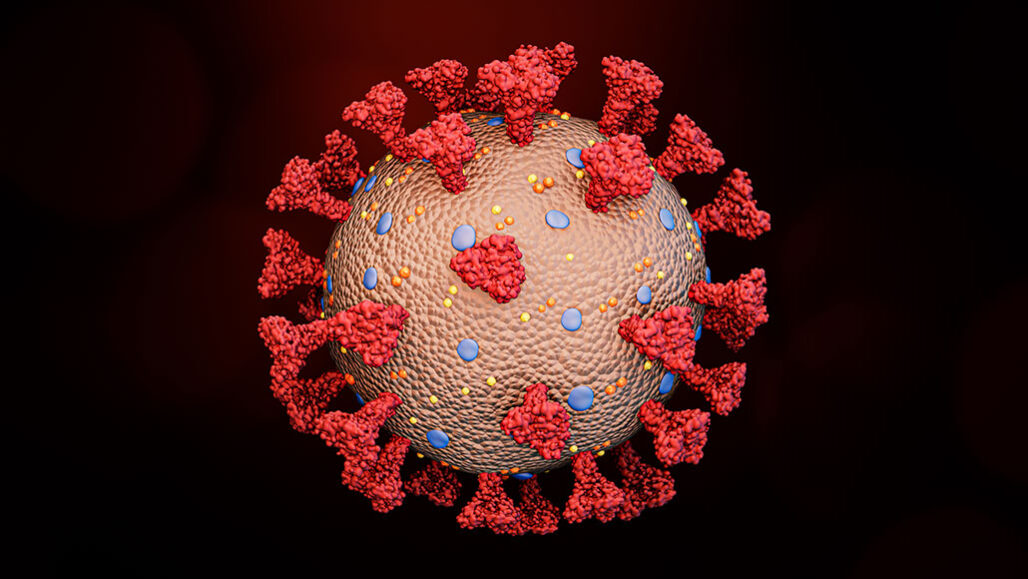

Changes to spike

Researchers spotted Omicron (called B.1.1.529 by epidemiology units) in genome-sequencing data from Botswana. The variant stood out because, as I noted above, it contained more than 30 changes to the spike protein — the SARS-CoV-2 protein that recognizes host cells and is the main target of the body’s immune responses. As I explained above, many of the changes have been found in variants such as Delta and Alpha, and are linked to heightened infectivity and the ability to evade infection-blocking antibodies.

Note: I wrote a long tutorial on this subject but in brief:

1. A protein is a compound made from one or more long chains of amino acids. Proteins are an essential part of all living organisms. They form the basis of living cells, muscle and tissues; they also do the work inside of cells. Among the better-known, stand-alone proteins are the hemoglobin (in blood) and the antibodies (also in blood) that attempt to fight infections. Medicines frequently work by latching onto proteins.

2. But one of the key biological characteristics of SARS-CoV-2, as well as several other viruses, is the presence of harmful spike proteins that allow these viruses to quickly penetrate host cells and cause infection.

3. Members of the coronavirus family have sharp bumps that protrude from the surface of their outer envelopes. Those bumps are known as spike proteins. They’re actually glycoproteins. Spiked proteins are what give the viruses their name. Under the microscope, those spikes can appear like a fringe or crown (and corona is Latin for crown).

The apparent sharp rise in cases of the variant in South Africa’s Gauteng province – home to Johannesburg – set off alarm bells. Cases increased rapidly in the province in November, particularly in schools and among young people, according to the Johns Hopkins briefing. Genome sequencing and other genetic analysis found that the Omnicron variant was responsible for all 77 of the virus samples (as noted in chart above) that were analysed from Gauteng. Analysis of hundreds more samples have been in the works over the last 4 days.

The variant harbors a spike mutation that allows it to be detected by genotyping tests that deliver results much more rapidly than genome sequencing does. Preliminary evidence from these tests suggest that Omicron has spread considerably further than Gauteng. South African health officials say the variant is already circulating quite widely in the country.

Note: as of this writing the only case in Europe is in Belgium. It is a Belgian who tested positive on November 22nd, was not vaccinated, and was returning from Egypt. She had not been to South Africa.

The biggie: vaccine effectiveness

To understand the threat Omicron poses, researchers must closely track its spread in South Africa and beyond. Researchers in South Africa mobilized efforts to quickly study the Beta variant, identified there in late 2020, and a similar effort is starting to study Omicron.

Penny Moore’s team (I referenced her above) which provided some of the first data on Beta’s ability to dodge immunity was already on Omicron for well over 2 weeks. Her team is testing the virus’s ability to evade infection-blocking antibodies, as well as other immune responses. According to the Johns Hopkins briefing:

“The variant harbors a high number of mutations in regions of the spike protein that antibodies recognize, potentially dampening their potency”.

In a press conference Moore noted that many mutations we know are problematic, but many more look like they are likely contributing to further evasion. That is the growing danger with COVID. There are even hints from computer modelling that Omicron could dodge immunity conferred by another component of the immune system called T cells, says Moore. Her team hopes to have its first full results in about two weeks.

But the burning question remains: does it reduce vaccine effectiveness, because it has so many changes? Moore’s team says breakthrough infections have been reported in South Africa among people who have received any of the three kinds of vaccines in use there, from Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer–BioNTech and Oxford–AstraZeneca. Two quarantined travellers in Hong Kong who have tested positive for the variant were vaccinated with the Pfizer jab, according to news reports. One individual had travelled from South Africa; the other was infected during hotel quarantining.

Researchers in South Africa will also need to study whether Omicron causes disease that is more severe or milder than that produced by other variants. The really key question comes around disease severity.

So in summary, the threat Omicron poses beyond South Africa is far from clear. It is also unclear whether the variant is more transmissible than Delta, although it certainly has the mutations to make it so. Countries where Delta is highly prevalent will need to closely watch for signs of Omicron.

This does not mean that the Omicron variant will fully escape vaccine or infection-elicited antibodies. It takes many, many mutations to fully escape neutralisation, and there are also T-cells.

T cells are part of the immune system and develop from stem cells in the bone marrow. They help protect the body from infection and may help fight cancer.

And on an upbeat note, the only (slightly) positive element is that a certain deletion on the spike protein means that it can be easily picked up through PCR testing, making it easier for the world to track.

Where is the mutation from? One Johns Hopkins scientist noted the genetic difference of Omnicron has led to the hypothesis that this may have evolved in someone who was infected but could then not clear the virus, giving the virus the chance to genetically evolve – the equivalent of an evolutionary gym. But it will be several more weeks or months before we know if it is also more deadly. Scientists have started lab experiments to see how well antibodies neutralise the virus, which will also give an indication of how much more infectious it is.

But I’d expect the Omicron variant to cause more of a hit on vaccines – and infection-elicited antibody neutralization – than anything we’ve seen so far. Aside from the theoretical science of why it could be more infectious and dangerous, real world data is needed – because at present it only suggests that Omicron could cause serious problems. We need to see what this virus does in terms of competitive success and whether it will increase in prevalence.

However, from what I have read about cellular immunity (and you can, too, here) I think the cellular immune response induced by vaccines may be sufficient to fight off the virus even with multiple mutations. Since the cellular immune response is very complex – generating new types of antibodies even against new variants – there is a chance vaccines will remain protective.