Just a few takeaways from the Wall Street Journal’s investigations

15 September 2021 (Rome, Italy) – I really want to talk about the Wall Street Journal’s ongoing investigation into Facebook’s internal research, and what it tells us about the blind spots we have in understanding how social networks affect society. The series is running all week and the amount of material is huge (fed by Facebook insiders). For this post we’ll just look at on part. Almost all of it is behind the Journal pay wall but this weekend I’ll “uncork it” and give you access.

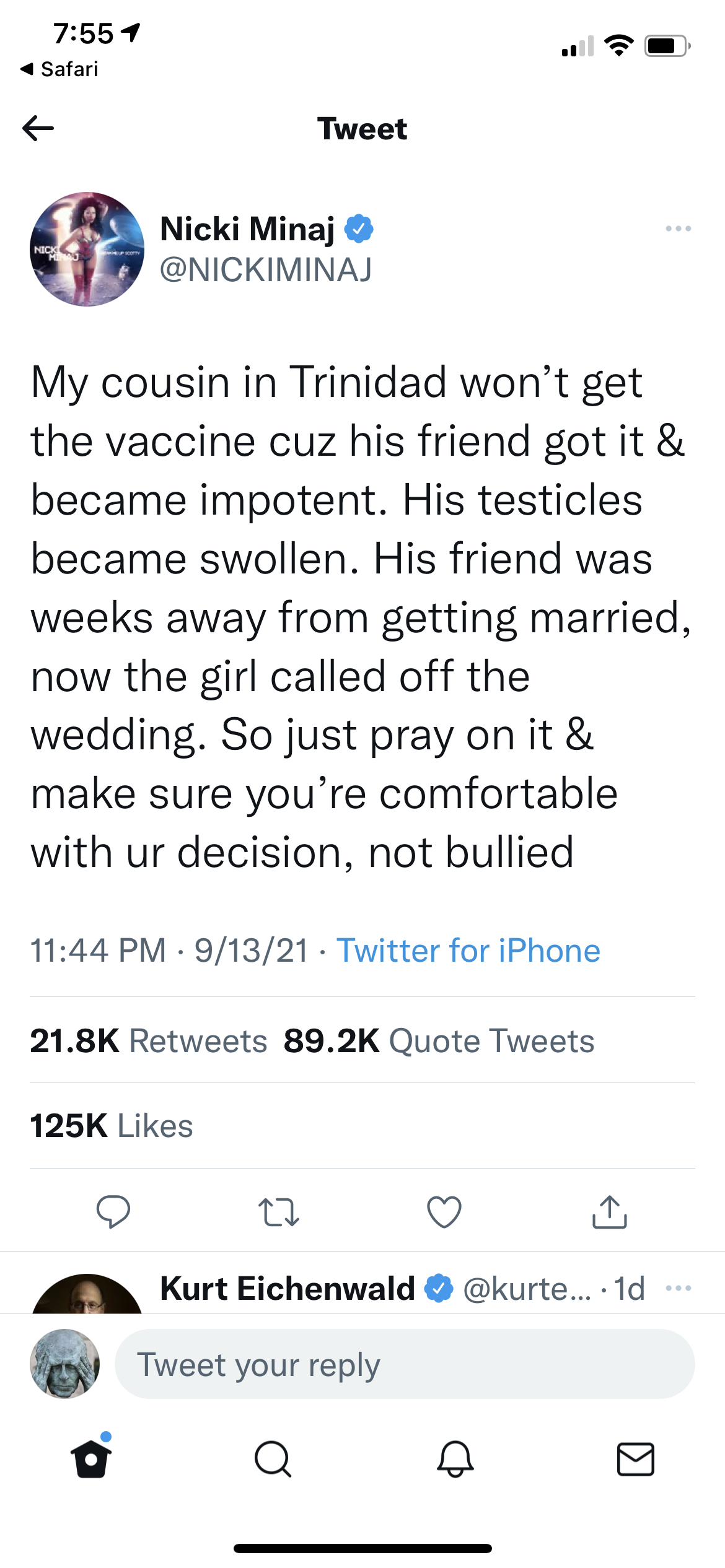

On Monday afternoon, the pop star Nicki Minaj posted an instantly legendary tweet about her vaccine hesitancy:

The backstory is here.

The tweet had everything: an insane story about balls, a called-off wedding, and just enough anti-vaxx sentiment to risk a terms-of-service violation. In the end, Twitter decided to let the post stand; the company didn’t even label it with a warning. That decision raised a question that comes up al the time in questions of content moderation: Would an average user have been treated the same, or did Minaj get kid-gloves treatment because she’s a celebrity — one with a hyperactive Twitter fan base?

The truth is that platform of any significant size effectively has two systems of justice: one for normal people, who typically have no recourse when decisions go against them; and another for VIPs, who benefit from additional layers of review and direct access to platform employees who will intervene on their behalf.

This disparity is at the heart of the Journal’s investigation this week into a system at Facebook known as XCheck. Pronounced “cross check,” the program is designed to give an added layer of review to content moderation decisions affecting high-profile accounts, including celebrities like Minaj, journalists, activists, government pages, and others in the public eye.

The existence of the program is well known — Facebook wrote a blog post about it in 2018 — but the Journal’s report drew from internal documents that describe a profound inequality. It begins with three quotes from Facebook employees who tell the story in miniature:

• “We are not actually doing what we say we do publicly.”

• “Facebook routinely makes exceptions for powerful actors.”

• “This problem is pervasive, touching almost every area of the company.”

An internal review of XCheck in 2019 found that most Facebook employees – involving 45 teams within the company – could add accounts to the list. By 2019, at least 5.8 million people had been added to the program.

I’ll get into the major points in a subsequent post but yesterday’s piece of the series – that Facebook knows Instagram is toxic for teen girls – is the most disturbing to date. As I write this post, the piece is behind the Journal pay wall (but that may have changed by the time this post is distributed) so just a few quotes from the piece:

About a year ago, teenager Anastasia Vlasova started seeing a therapist. She had developed an eating disorder, and had a clear idea of what led to it: her time on Instagram.

She joined the platform at 13, and eventually was spending three hours a day entranced by the seemingly perfect lives and bodies of the fitness influencers who posted on the app.

“When I went on Instagram, all I saw were images of chiseled bodies, perfect abs and women doing 100 burpees in 10 minutes,” said Ms. Vlasova, now 18, who lives in Reston, Va.

Around that time, researchers inside Instagram, which is owned by Facebook Inc., were studying this kind of experience and asking whether it was part of a broader phenomenon. Their findings confirmed some serious problems.

“Thirty-two% of teen girls said that when they felt bad about their bodies, Instagram made them feel worse,” the researchers said in a March 2020 slide presentation posted to Facebook’s internal message board, reviewed by The Wall Street Journal. “Comparisons on Instagram can change how young women view and describe themselves.”

For the past three years, Facebook has been conducting studies into how its photo-sharing app affects its millions of young users. Repeatedly, the company’s researchers found that Instagram is harmful for a sizable percentage of them, most notably teenage girls.

“We make body image issues worse for one in three teen girls,” said one slide from 2019, summarizing research about teen girls who experience the issues.

“Teens blame Instagram for increases in the rate of anxiety and depression,” said another slide. “This reaction was unprompted and consistent across all groups.”

This is colossal. In public, Zuckerberg has said, under oath, that using social media canhave positive mental health benefits. But he knew it often doesn’t.

Meanwhile, one of the most vocal critics of children’s use of social media, Professor Jonathan Haidt, wrote a Twitter thread in which he said he sees “no way to fix Instagram for minors… I wish I could raise my daughter in a world that had no such platforms”.

A number of media outlets have commented (all accessible) which I’ll share:

• One internal Facebook presentation said that among teens who reported suicidal thoughts, 13 percent of British users and 6 percent of American users traced the issue to Instagram. (CNBC)

• The newspaper obtained and published slides from presentations in which researchers summarized the findings of what they called a “teen mental health deep dive,” including a study which found Instagram makes “body image issues worse for one in three teenage girls.” (Forbes)

• The dive into Instagram’s impact is made up of focus groups, diary studies and surveys of tens of thousands of people. In five presentations over 18 months, researchers found that some of the problems were specific to Instagram, and not social media in general, according to the WSJ. (Al Jazeera)

More to come.