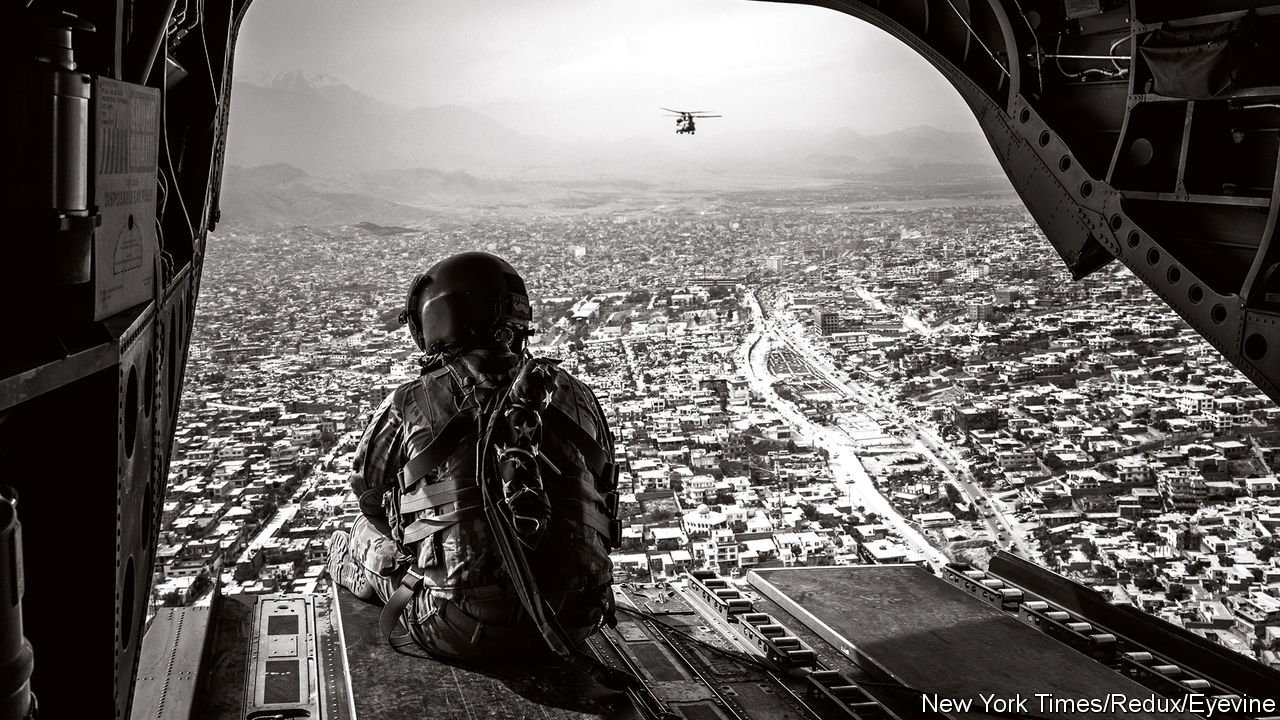

America is leaving Afghanistan back at Square One. After 20 years of war, it is a sobering failure.

Well, maybe “back to Square One” is too generous. The Taliban have been allowed to gain back almost 50% of the territory, without having to fight too much for it. So maybe it’s “Square Minus One”.

Herein my thoughts on a war I had stopped thinking about years ago but began reading about again as I attacked my ever-growing “stuff to read” stack.

25 July 2021 – “I want to talk about happy things, man!” protested President Joe Biden in early July, The Economist reported, when reporters asked him about the imminent withdrawal of the last American forces from Afghanistan. No wonder he wants to change the subject: America has been fighting in Afghanistan for 20 years.

Hmmm. Perhaps a correction is in order: it’s actually not 20 years but more like 43 years. America was conducting war on Afghanistan since 1979 first using the mujahadeen as proxies. The blowback included the Taliban, al Qaeda, and ISIS. It may be Square One or Square Minus One in Afghanistan, but for the rest of the world it is minus several squares.

The U.S. has spent more than $2trn on the war. It has lost thousands of its own troops and seen the death of tens of thousands of Afghans – soldiers and civilians alike. Now America has called an end to the whole sorry adventure, with almost nothing to show for it.

What a record. The British lost, the Soviets lost, the American lost.

True, al-Qaeda, which sparked the war by planning the 9/11 attacks from Afghanistan, is no longer much of a force in the country, although it has not been eliminated entirely. But that is about as far as it goes. Other anti-American terror groups, including a branch of Islamic State, continue to operate in Afghanistan. The zealots of the Taliban, who harbored Osama bin Laden and were overthrown by American-backed forces after 9/11, have made a horrifying comeback. They are in complete control of about half the country and threaten to conquer the rest. The democratic, pro-Western government fostered by so much American blood and money is corrupt, widely reviled and in steady retreat.

I wonder how the American taxpayers feel about it. They bail out the bankers and subsidize the military which plays global sheriff – while there is no U.S. universal health care. Good system.

In theory, the Taliban and the American-backed government are negotiating a peace accord, whereby the insurgents lay down their arms and participate instead in a redesigned political system. In the best-case scenario, strong American support for the government, both financial and military (in the form of continuing air strikes on the Taliban), coupled with immense pressure on the insurgents’ friends, such as Pakistan, might succeed in producing some form of power-sharing agreement.

But even if that were to happen (and a friend of mine in the U.S. diplomatic corps says chances of that are pretty low) it would be a depressing spectacle. The Taliban would insist on moving backwards in the direction of the brutal theocracy they imposed during their previous stint in power, when they confined women to their homes, stopped girls from going to school and meted out harsh punishments for sins such as wearing the wrong clothes or listening to the wrong music.

More likely than any deal, however, is that the Taliban try to use their victories on the battlefield to topple the government by force. They have already overrun much of the countryside, with government units mostly restricted to cities and towns. Demoralised government troops are abandoning their posts. Last week over 1,000 of them fled from the north-eastern province of Badakhshan to neighboring Tajikistan. The Taliban have not yet managed to capture and hold any cities, and may lack the manpower to do so in lots of places at once. They may prefer to throttle the government slowly rather than attack it head on. But the momentum is clearly on their side.

At the very least, the civil war is likely to intensify, as the Taliban press their advantage and the government fights for its life. Other countries – China, India, Iran, Russia and Pakistan – will seek to fill the vacuum left by America. Some will funnel money and weapons to friendly warlords. The result will be yet more bloodshed and destruction, in a country that has suffered constant warfare for more than 40 years. Those who worry about possible reprisals against the locals who worked as translators for the Americans are missing the big picture: America is abandoning an entire country of almost 40m people to a grisly fate.

It did not have to be this way. For the past six years fewer than 10,000 American troops, plus a similar number from other NATO countries, have propped up the Afghan army enough to maintain the status quo. American casualties had dropped to almost nothing. The war, which used to rile voters, had become a political irrelevance in America. Since becoming president, Biden has focused, rightly, on the threats posed by China and Russia. But the American deployment in Afghanistan had grown so small that it did not really interfere with that. The new American administration views the long stalemate as proof that there is no point remaining in Afghanistan. But for the Afghans whom it protected from the Taliban, the stalemate was precious.

There will be a long debate about how much the withdrawal saps America’s credibility and prestige. For all its wealth and military might, America failed not only to create a strong, self-sufficient Afghan state, but also to defeat a determined insurgency.

And that points to my biggest military take-away: maybe this should put an end to expeditionary counterinsurgency, which is different from colonial counterinsurgency. A foreign power cannot do coin like a host government can à la Sri Lanka or Colombia.

What is more, America is no longer prepared to put its weight behind its supposed ally, the Afghan government, to the surprise and dismay of many Afghan officials. Hostile regimes in places like China and Russia will have taken note – as will America’s friends.

That does not make Afghanistan a second Vietnam. For one thing, the Afghan war was never really the Pentagon’s or the nation’s focus. American troops were on the ground far longer in Afghanistan than they were in Vietnam, but far fewer of them died. Other events, from the war in Iraq to the global financial crisis, always seemed more important than what was happening in Kandahar. And American politicians and pundits have agonised over whether to stay or go for so long that now that the withdrawal has finally arrived, it has lost its power to shock. To the extent that outsiders see it as a sign of American weakness, that weakness has been evident for a long time.

Shocking or not, though, the withdrawal is nonetheless a calamity for the people of Afghanistan. In 2001 many hoped that America might end their 20-year-old civil war and free them from a stifling, doctrinaire theocracy. For a time, it looked as though that might happen. But today the lives of ordinary Afghans are more insecure than ever: civilian casualties were almost 30% higher last year than in 2001, when the American deployment began, according to estimates from the UN and academics. The economy is no bigger than it was a decade ago.

And the mullahs are not only at the gates of Kabul; their assassins are inside, targeting Shias, secularists, women with important jobs – anyone who offends their blinkered worldview.

America was never going to solve all Afghanistan’s problems, but to leave the country back at Square One is a sobering failure. But then again, I’m a cynic. The point was never to “win a war”. It was to simply be at war somewhere for as long as possible, and reap more and more profits for the defense contractors.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

There was no plausible response to 9/11 that kept the Taliban and its deadliest guests in place. At the same time, the prospect of securing a land that had confounded two empires was fanciful. What you are left with is the most eminent case in my lifetime of a perfect problem: one to which there is no good answer. It could not be left alone and it could not not be left alone.

As most guys my age, I did my stint in the military. Me? The U.S. Marine Corps. Semper Fi! Besides learning how to iron my new uniform and polish my boots, I learned about strategy. And when I began to read about, follow Afghanistan it did not take me too long to realize the Bush administration went in without a strategy at all. Not a smart thing to do in an Asian land war.

And what I never understood (where in hell were the military thinkers!) was why the Bush administration divided its small army between two massive land wars in Asia. No, I did not need to learn that at the U.S. War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Massive, basic strategic failures to think ultimately resulted in something resembling intractable and impossible to manage chaos. There’s a fine a line between arrogance and confidence as there is between stupidity and bravery, but there’s no place for uncertainty or hesitancy or proper allocation of assets on the battlefield. Individuals and teams get in trouble when they get caught in vulnerable positions, uncertain of their objectives or location.

And any basic reading of history will tell you that Afghanistan isn’t a “nation state” governed by some sort of central control. It is a set of tribes bound by blood and local geography with no allegiance to the capital. Afghans have the benefit of several thousand years of genetic adjustment to their very specific terrain such that individual fighters can run up and down extremely tough terrain all day long wearing flip flops and eating a piece of nan bread. Fighting a nomadic and religious group (with limitless supply of suicide bombers) with a formal/civilised war machine is a lost cause.

And U.S. officials (and almost every pundit) were apparently unable to recognise that the Taliban had a constituency of support in Afghanistan, as repulsive as their governing principles were, from their ban on women’s education and most work, to their embrace of punishments like flogging and amputation and public executions.

Why? Because of the dozens of relatives who were killed at the hands of the foreign forces that first appeared in their midst nearly 20 years ago. The worst – the most notorious massacre of the war – was when when U.S. SSgt Robert Bales walked out of a nearby base to slaughter local families in cold blood. He killed 16 people, nine of them children. And those murders may have been the most high-profile civilian deaths of the war but it was not the only time foreign forces killed large numbers of women, children and non-combatant men, in just this one corner of a single district of Afghanistan.

America’s tragedy, thousands of families’ terrible losses on that September morning in 2001, would indirectly unravel into similar grief for thousands of other families half a world away. Afghans who knew little or nothing about the planes flying into towers in New York, and certainly had no link at all to al-Qaida, were caught up in the war that followed, and that claimed 100s of their loved ones year after year.

In contrast (and I did learn this at the U.S. War College), the Truman administration fought the Korean War with a tight, very tight grip on its objectives, played for a tie, and ultimately won the biggest strategic prize of the entire Cold War era short of the ultimate triumph. Sometimes clear thinking works.

But it is stunning how the U.S. experience parallels the Russians. In other words, no matter what your values, no matter how much time you spend or how many soldiers you lose, no matter whether you’re on the winning or the losing side in geopolitical battles, what you’ll leave behind in Afghanistan are scenes of looting, a weak regime too dependent on your support and unlikely to hold out much longer, tough local fighters who feel vindicated for years of hardship, and gloating Pakistani generals across the border. Another constant: Afghanistan’s flourishing opiate industry, which neither the Soviets nor the Americans could undermine.

These enduring circumstances have less to do with the stubborn magic of the place than with the simple fact that, as much as the Soviets of the 1980s and the Americans of this century’s first two decades differ from one another, both stepped into Afghanistan with too little forethought and too much arrogance and confidence – and knew from the start that they couldn’t stay. Both were certain of their superior military might and their superior values. Both found evidence that some locals liked what they brought – each their own brand of secular progressivism – and took that to mean those values could take root. But neither could stick around forever; colonization just isn’t done anymore, and Gorbachev was no more prepared to entertain it than Joe Biden. Afghanistan hasn’t been worth holding on to for either of them, given its hefty human and financial cost.

To the Taliban, though, just as to the assorted Afghan rebels before them, their entire purpose and meaning were in staying there forever. The local fighters felt in 1989, and still feel in 2021, that they stand for the country and its way of life. The Taliban can be particularly convincing about it. If you’re not going anywhere no matter what happens, and can deal with what price you’re forced to pay over however long, you can outlast superpowers. Attachment to a place and a way of life is a powerful constant that, as Afghanistan’s example shows, creates other constants.

If “hope” has limits, if some crises are intractable, it is easier to break the news to victims (better placed than most to be realistic) than their would-be saviors. I have spent long enough on the journalistic trail, spent enough time seeing the sausage being made and certainly read enough to know (as you, my readers, certainly know) that it is not malice or arrogance that defines the world so much as it is naivete. There is less disdain for the masses than overconfidence in what policy can do for them against mulish, foot-dragging reality. The timelessness of social problems, the perverse consequences of change, the role of futility in human affairs: it is possible to be sublimely educated and yet screened from these verities.

Yes, it does require some reading time, some thought time to stay abreast. This, in the end, is what the relative neglect of the Afghan war comes down to. The modern incapacity for despair. Most wars connote glory (the second world war) or folly (Iraq), either of which is a guide to future action.

This one was not a teachable moment so much as an extended riddle. It was right to go in and yet it was hopeless to go in. We have to leave and it is rash to leave. We were always going to get lost in such ambiguity. We had to go in; and then had to leave. Trying to fight with different levels of morality failed for the Russians, it failed for the Americans, and now it appears the Chinese are dipping their toes into Alexander the Great’s old mountains, too. But they are looking more for trade deals, not nation building.