Some background to my series “Cyber (in)security: some thoughts, musings and parables (a work-in-progress)”

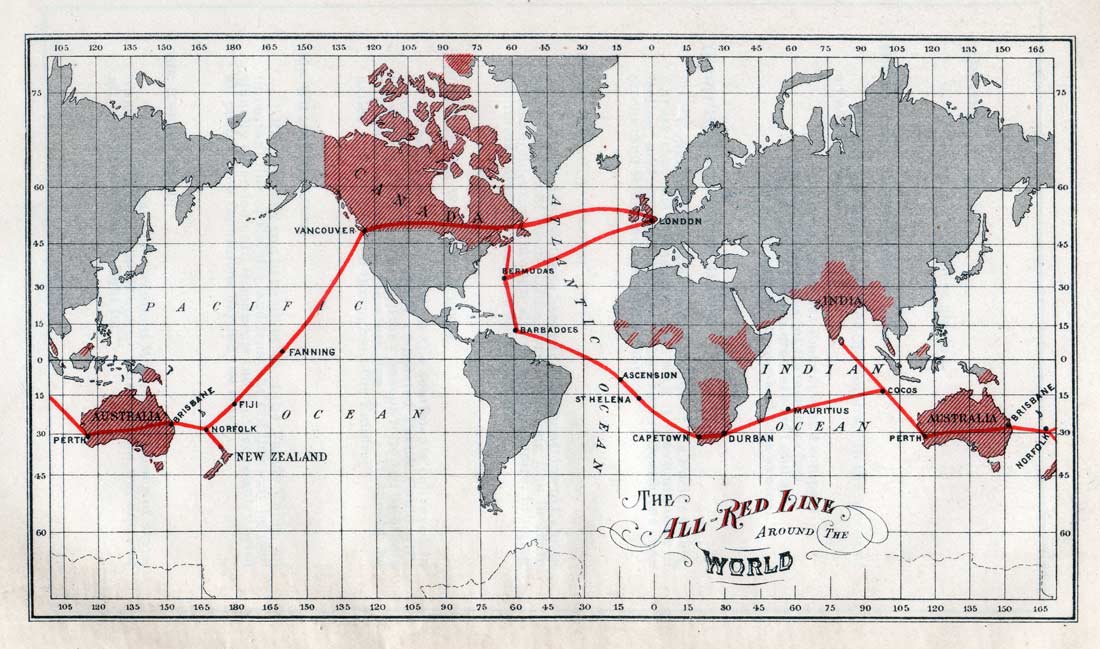

Much, if not all, British long-distance telecommunication relied on the “All-Red Line”, the network of British-controlled and operated electric telegraph cables stretching around the globe and so called due to the color red (or sometimes pink) being used to designate British territories and colonies in the atlases of the period.

15 July 2021 – The “All-Red Line” was operated through a mixture of public and private enterprise with the Eastern Telegraph Company operating many of the telegraph cables in Asia, Africa, and beyond. By the late nineteenth century, telegraphy cables from Britain stretched to all corners of the globe forming a massive international communications network of around 100,000 miles of undersea cables.

News which had previously taken up to six months to reach distant parts of the world could now be relayed in a matter of hours. In 1902 the “All Red Line” route was completed with the final stages of constuction of the trans-Pacific route and connected all parts of the British empire.

This telegraph network consisted of a series of cable links across the Pacific Ocean, connecting New Zealand and Australia with Vancouver and through the Trans-Canada and Atlantic lines to Europe. Submarine telegraph cables remained the only fast means of international communication for 75 years until the development of wireless telegraphy at the end of the nineteenth century.

Security and telegraph cables

Security and reliability were an important part of this vast international telecommunications network: there were multiple redundancies so that even if one cable was cut, a message could be sent through many other routes, operating a bit like the modern day Internet (which actually has far more redundancies built in). Further security was added in the location of telegraph line landfall: the “All-Red Line” was designed to only made landfall in British colonies or British-controlled territories although this may have compromised on occasionally.

In 1902 and around the time that the All-Red Line was completed, the Committee of Imperial Defence was established by the then British Prime Minister Arthur Balfour and was made responsible for research and some coordination of British military strategy. In 1911 and with the possibility of a war in Europe looming, the committee analysed the All-Red Line and concluded that it would be essentially impossible for Britain to be isolated from her telegraph network due to the redundancy built into the network: 49 cables would need to be cut for Britain to be cut off, 15 for Canada, and 5 for South Africa. Further to this, Britain and British telegraph companies owned and controlled most of the apparatus needed to cut or repair telegraph cables and also had a superior navy to control the seas.

War approaches

In December 1913, the War Office drew up “Regulations for censorship of submarine cable communications throughout the British Empire” with the possibility of war with Germany again coming to the fore. The aims of these stricter regulations controlling the management of the electrical telegraphy and wireless telegraphy infrastructure were multiple: to deny naval or military intelligence to the enemy; to prevent the spread of false reports to detecting the morale of civilian population; to collect and distribute enemy information to government departments; to deny the use of British cables to any person – British, Allied, or neutral – for commercial transactions with the enemy while interfering as little as possible with legitimate British and neutral trade. Although initially suggested and guided by the War Office, the regulations were managed, implemented and communicated by the General Post Office who were the British government department allocated responsibility for managing the domestic telecommunications monopoly and related licensing. Commercial telegraph companies fell in line rather than face revocation of their inland telegraph licence, with commercial wireless telegraphy also agreeing to abide with the regulations for similar, commercially minded reasons.

By mid-1914, Britain was at the centre and in control of a vast network of global telegraph cables with most of the world’s long-distance communication passing through these cables as well as the central telegraphic hub that was London. Wireless telegraphy had not yet eaten into the telegraph network’s traffic or operations: the German imperial wireless telegraphy network was only partially complete at the outbreak of war in August 1914 and the British Imperial Wireless Scheme had been put on hold in the aftermath of the “Marconi scandal” in 1912 and remained so throughout the war.

At the outbreak of war, wireless telegraphy was perceived and presented by the British military as “a valuable reserve in addition to cable communication” rather than of strategic importance in its own right. This vast global telegraphic network as well as its control was considered of immense strategic importance to businesses, government, and military and a keystone in the imperial and military activities of many nations including Britain and Germany, in particular the British ‘infrastructure state’ and empire.

As a result, following the formal declaration of war between Britain and Germany on the evening of 4 August 1914, one of the first acts by the British was to send out cableships with secret orders to destroy and divert German undersea telegraph cables. Resulting from these British actions at the outbreak of war, Germany’s long-distance telecommunications were severely limited: only one German telegraph cable passing through the English Channel was left intact but even this was under British control and any message sent through it could be intercepted and read by British government code breakers based at “Room 40” at the Admiralty in London.

Further to this, Germany was forced to send communications through neutral cables or via their incomplete Imperial Wireless Scheme, both of which could be easily intercepted by the British who attacked and exploited these long-distance networks for vital signals intelligence. This came to fore later in the war with the British interception and decryption of the controversial Zimmermann telegram in 1917, which led, in part, to US entry into the war.Although Germany had competed with Britain in terms of naval and telegraphic networks and technology in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, they lacked the hegemony of Britain in both regards and so were forced to take a different tack when it came to attacking the Allied and British telegraph network.

Initially, Germany and her allies focused on attacking the telegraph cable network at its weakest point: geographically isolated relay stations. German naval vessels attacked and destroyed British telegraph stations and cut nearby cables in the Pacific and Indian Oceans with notable attacks on Fanning Island and the Cocos Islands in late 1914. However, with the failure of these attacks, the German navy began following the British example and cut telegraph cables at various points instead. Some of these attacks were committed by the crews of German U-boats and this aspect of submarine warfare continued beyond the introduction of unrestricted German U-boat attacks on enemy and neutral vessels in early 1917 until the end of the war. Notable attacks included a German naval attack on the telegraph cable between Britain and Norway in mid-1915 as well as later attacks on the cable telegraph network on the eastern seaboard of the US in 1917.

These attacks by almost all belligerents involved in the conflict continued in various forms throughout the war. The changing nature of attacks on the telegraph network also reflected wider changes in the telecommunications infrastructure during the war. By the middle and late stages of the war, a combination of difficulty in maintaining the telegraph network – cableships were slow and unarmed and hence vulnerable to attack – as well as advances in long-distance wireless telegraphy technology and infrastructure, including early short-wave wireless systems, led to a decrease in the strategic importance of the telegraph network and hence attacks on the infrastructure.

This decline continued after the war with maintenance of wireless telegraphy infrastructure being signifcantly easier and cheaper than that of the electrical telegraph network.